Prisoner of War: A Canadian Warplane Heritage Member’s Story

On 23 November 1943, during Grove’s third mission over Berlin in five nights, a German fighter suddenly opened fire on his Lancaster, killing the rear gunner and mid-upper gunner. Then the enemy plane hit the bombs the Lancaster was carrying and Grove’s aircraft became a torch in the night sky. He forced the aircraft into a dive to try and blow out the flames, but his efforts were unsuccessful.

Grove and his surviving crew were four hours away from base with only three engines working, no functioning weapons and short of gasoline. Also, trying to fly back to England would make them a flaming target all the way. Grove had no choice but to tell his crew to jump for their lives. As the others jumped, he tried to keep the plane as steady as possible, observing the rule that the pilot always jumps last.

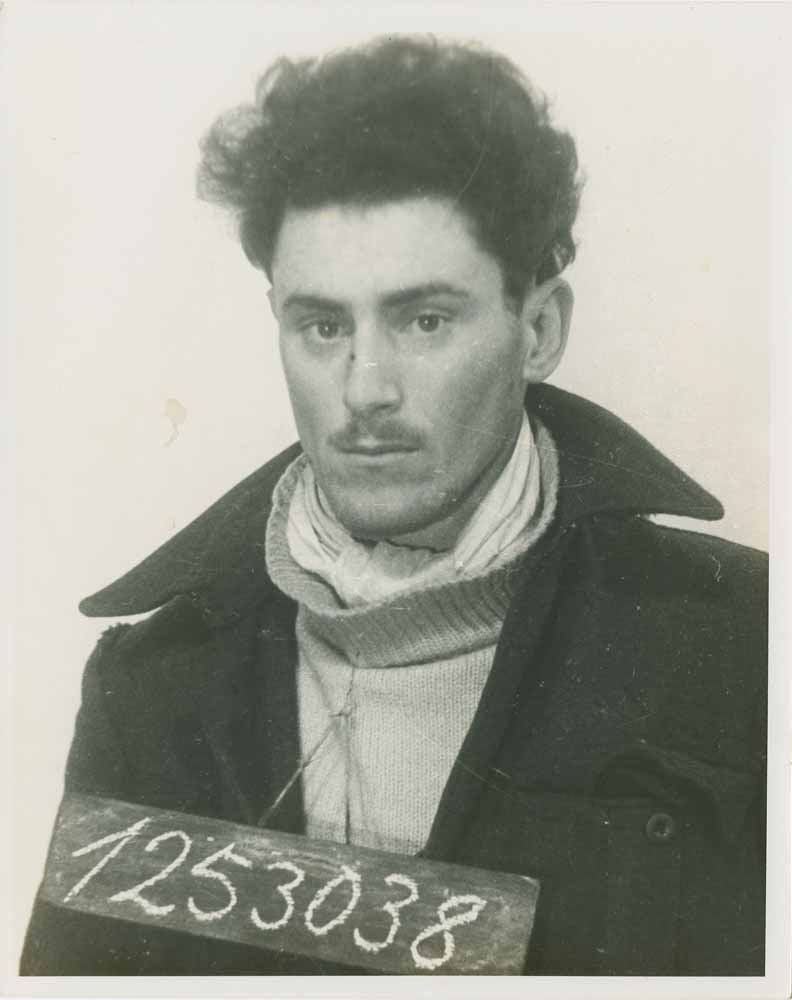

Finally it was Grove’s turn to jump. After landing in some trees and burying his parachute under snow and leaves, guided by his compass, he started to walk north, hoping to get to Sweden. He soon saw a convoy of German army trucks parked along the side of a road and attempted to jump in the back of one. Just as he was about to get inside, a German solider spotted him and pointed a bayonet at him. Grove was now a prisoner and was taken for questioning. He was prepared; downed airmen expected to be questioned for information about the Allied war effort.

Grove was then sent from Berlin to Frankfurt in a train which picked up other prisoners along the way. He spent approximately one week in interrogation before being shipped out again. The first camp he was sent to in Lithuania was full, so he was moved on to Stalag III, but that camp was also full. Finally, he joined approximately 20,000 other prisoners of war at camp Stalag IVB. All nationalities of Europe were being held there, including about 10,000 Russians. Conditions were unpleasant and unclean; showers were taken once every two weeks with either very cold or very hot water only. In addition, prisoners were given one small can of water per week for shaving and washing. They all had lice and most of the men had open sores from scratching at them.

Grove was then sent from Berlin to Frankfurt in a train which picked up other prisoners along the way. He spent approximately one week in interrogation before being shipped out again. The first camp he was sent to in Lithuania was full, so he was moved on to Stalag III, but that camp was also full. Finally, he joined approximately 20,000 other prisoners of war at camp Stalag IVB. All nationalities of Europe were being held there, including about 10,000 Russians. Conditions were unpleasant and unclean; showers were taken once every two weeks with either very cold or very hot water only. In addition, prisoners were given one small can of water per week for shaving and washing. They all had lice and most of the men had open sores from scratching at them.

A telegram sent at Christmas of 1943 informed Grove’s family that he was missing in action. The family wouldn’t learn that he had survived his crash until they read it in a newspaper in the spring of 1944. The only contact the prisoners had with the outside world was a radio which they kept hidden away. They hid the radio in the one place they knew the Germans wouldn’t look—in the seat of the Commanding German Officer’s chair! They observed that the German C.O. left promptly after he finished work at 6:00 pm every day. That’s when they would retrieve their radio to listen to the BBC all night!

By 1945 food became scarce all over Germany and the prisoners’ meager rations began to dwindle. Grove had lost fifty-sixty pounds and was starting to lose his ability to walk. One morning he and the other prisoners woke up to find that the German guards had simply disappeared; they had left in the night to avoid the advancing Russian troops. The prisoners, many of them too sick to move, were trapped between two armies, the Germans and the Russians. Finally, the Russian Army reached the camp and Grove and the other prisoners were sent to the nearby small town of Riesa.

Shortly after their arrival in the town, the Russians announced that a prisoner exchange deal had been struck. Despite the USA and the Soviet Union being allies in the war, a current of tension which would lead to the Cold War was already in the air. The U.S. Army had agreed to swap Russian for American and British prisoners, but only one at a time. The prisoners soon realized that there were many more of them than Russians and started to worry that they might not all be freed. Then, a Russian guard signaled for all the Allied prisoners to go, and they scrambled to make it across the bridge before he could change his mind. Grove was weak and dehydrated, but made it across the bridge by crawling on his hands and knees. From there he was flown to Brussels for emergency care and then he was returned to England. Finally, after 3 years as a prisoner of war, Grove was a free man, weighing less than 100 pounds.

At only twenty-four years of age, Eric Grove was an RAF veteran who had barely survived life in a P.O.W. camp. Now, over sixty-five years later, Grove, an active member of the Canadian Warplane Heritage, has shared his incredible story with us.