A British Teenager Caught Up in the First World War: William O’Sullivan Molony

William O’Sullivan Molony is only seventeen as he starts his diary and welcomes in the New Year at home in Eastbourne, England, with family, friends and German relatives in January 1914. Already a graduate of Wellington College, he is cramming in preparation for the Oxford University entrance examinations. His father is dead and his step-father, a German military officer, has by then been dead for two years. Together with his mother and sister, he travels to Germany on 25 March. William spends a delightful spring and summer there, and falls in love with his American cousin, Charlotte. At his mother’s urging and buttressed by assurances that England would remain neutral, he lingers in Germany and then finds himself, quite unexpectedly, unable to leave. On 7 August he was arrested but then let go. The diary ends on 16 September 1914, several weeks before he is sent to Ruhleben civilian internment camp, formerly a race-course, in November of that year. His mother, who had urged him to stay on in Berlin, is allowed to leave the country, as are all non-German women.

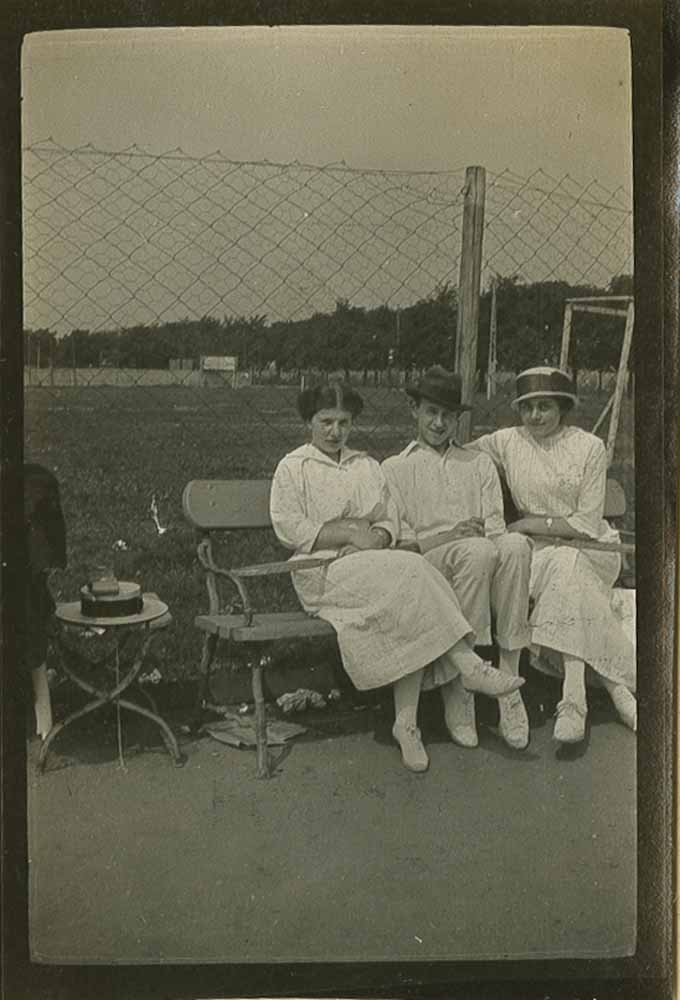

The right-hand pages of the diary, handwritten in ink, with photographs pasted in, have been numbered in pencil as far as page 71. Archival staff have numbered the remaining pages to 124. The remainder of the diary contains blank pages. Occasionally some text and poetry has been written, photographs pasted, or sketches made on the left-hand pages, but they have not been numbered. At page 72, the handwriting changes but Molony’s “voice” does not. Did someone else copy the remainder from Molony’s notes? Or is he, as many young people do, just experimenting with his handwriting? The captions below the photographs are in a different, more stylized hand, as is his poetry. There are some oddities in the later text: e.g. in early August (p. 93), he writes of troops at the Front “lying for weeks in their damp entrenchments” – this at a time when war had just been declared and few troops had been mobilized. How did the diary survive? Did a family member remove the diary from Germany in September 1916? Were parts of it added later, and if so, by whom?

The right-hand pages of the diary, handwritten in ink, with photographs pasted in, have been numbered in pencil as far as page 71. Archival staff have numbered the remaining pages to 124. The remainder of the diary contains blank pages. Occasionally some text and poetry has been written, photographs pasted, or sketches made on the left-hand pages, but they have not been numbered. At page 72, the handwriting changes but Molony’s “voice” does not. Did someone else copy the remainder from Molony’s notes? Or is he, as many young people do, just experimenting with his handwriting? The captions below the photographs are in a different, more stylized hand, as is his poetry. There are some oddities in the later text: e.g. in early August (p. 93), he writes of troops at the Front “lying for weeks in their damp entrenchments” – this at a time when war had just been declared and few troops had been mobilized. How did the diary survive? Did a family member remove the diary from Germany in September 1916? Were parts of it added later, and if so, by whom?

Selected pages from the diary, with transcriptions, have been chosen to illustrate Malony’s young and carefree life before war clouds loomed. The latter part of the diary, which describes Berlin as war descends, has been reproduced in its entirety. Also available is a sketch of his which appeared in the Ruhelben Camp magazine and an advertisement for that magazine.

Selected pages from the diary, with transcriptions, have been chosen to illustrate Malony’s young and carefree life before war clouds loomed. The latter part of the diary, which describes Berlin as war descends, has been reproduced in its entirety. Also available is a sketch of his which appeared in the Ruhelben Camp magazine and an advertisement for that magazine.

We know from his autobiography that Malony survived two years at Ruhleben civilian internment camp. In 1916 he tried to escape, was captured and sent to Stadtvogtei prison in Berlin, which had housed criminals before the war. He survived days of solitary confinement in a dark cell before he was given more freedom. After six months at Stadtvogtei, he was sent to a punishment camp in Havelberg, where he endured another two years. Just before the end of the war, he was returned to Ruhleben. Once the gates were opened, and utterly alone, he made his way into Berlin, a city in chaos, and found refuge in his sister’s apartment, although she was no longer there. He collapsed in fever. As he writes in Prisoners and Captives: “I had had dysentery, enteric, typhus and other diseases. Since the end of 1914, not one drop of fresh milk had passed my lips; since the middle of 1915 I had tasted no recognizable fresh meat. I had lived entirely on nervous energy.”

In the book, he places the blame for his “adventure” on the American girl (without mentioning that she was his cousin), instead of his mother. One wonders about the torment his mother must have endured during the war, not knowing in the latter stages if her son was even alive. But in his book, New Armour for Old, there is no mention of her – only a “very gentle and aged grandmother, a sensible great-aunt and a too sensible sister” to greet him on his return to England. Molony entered Oxford, worked for a number of years at the League of Nations, and after ill health forced him to resign, wrote Prisoners and Captives from memory. After the publication of his 1935 book, nothing further is known of William Molony.

Some of the characters who appear in the diary:

FAMILY

Mrs. Molony-Uhse, William’s mother, a widow. After the death of Molony’s father, an Irishman, she had married a German officer who has been dead for two years at the time of the diary’s writing.

Lillie, William’s sister, mother of Jackie; who goes to Germany with William and their mother. She leaves Jackie in Berlin and spends some time with Margaret. At some point she leaves Germany as William notes that she is returning on 29 July 1914 with Dorothy Ireland.

Jackie, also called Jacky and Jack, Lillie’s son who is cared for by a nurse. Jack turns three in June 1914

Kathleen, William’s unmarried sister, who leaves for America with Edna Groves (of Eagle Pass, Texas) in January 1914 and returns with Charlotte on 25 May 1914.

Margaret, William’s sister (?) and wife of Gert, a Germany cavalryman.

Fritz Uhse, German uncle and officer

Gert Uhse (?) possibly Rohde or Rittmeister, German cousin and officer married to Margaret

Charlotte, the diarist’s American cousin, with whom he falls in love. She was from Eagle Pass, Texas. Usually called C. One of William’s grandfathers was American.

Jack, Charlotte’s American sweetheart or fiancé, an Army officer.

FRIENDS AND OTHERS

Lillie Lahmayer and Hermina Appenthern, the proprietors of Lahmayer’s, a language “school” in Hannover.

Mathilda Appenthern, William’s German teacher in Hannover

Madame Léonard, proprietor of a language “school” in Versailles.

P.K. (Patrick Kenny), friend of William’s who had previously been at Lahmayer’s

Friends of William studying at Lahmayer’s: Edward Cunard, Guy Colebrooke, Patrick Duff (nicknamed “Puff”), Oliver Lawrence, Harvey, Des Gratz (an Irishman), Edward Thornton. Many of them are older than him, already finished their university education. Annie, a ballet girl at the M.R.; also worked at the P. de D., a restaurant in Hannover, frequented by William and his friends.

A warning: some offensive language is used in this diary, entry of 7 August 1914.

Some German text has not been transcribed.

Molony, William O’Sullivan. New Armour for Old (London: Victor Gollancz, 1935)

Molony, William O’Sullivan. Prisoners and Captives (London: Macmillan, 1933)

The Ruhleben Camp magazine (1916-[1917])