Alex Aronson, Volunteer Medical Worker and Humanitarian

Alex Aronson (Leendert or Lex) was born on 20 December 1934 in Amsterdam. When he was eight years old, he was deported with his mother and maternal grandparents through Westerbork Transit Camp to Bergen-Belsen. His grandfather died of exhaustion in the summer of 1944. As his first-cousin, Gershon Eisenmann related, “In early April 1945, when the allies were nearing the neighborhood of Bergen-Belsen, the Germans transported everybody who could still walk a little bit out of Bergen-Belsen in two trains. Their intention was to drive the trains into the River Elbe. This never happened, and the trains drove aimlessly through Germany.” For thirteen days, Alex’s train pushed on until it was freed by the Russians in eastern Germany. During this period, his mother fell seriously ill with typhus. Alex, then ten years old, nursed his mother back to health. Alex’s grandmother never made this trip. She was left behind by the authorities as too sick for the journey; her family never saw her again.

Between 1945 and 1947, Alex recuperated from tuberculosis in Switzerland. Returning to Amsterdam, he attended the Hogere Burger (Jewish Secondary) School (1948-51). In 1952, he received a certificate in chiropody. For the next three years, he studied nursing at the Jewish Hospital in London. Already his interest in healing the sick was clear.

At the beginning of 1961, Aronson decided to hitch-hike to Albert Schweitzer's mission hospital in Lambaréné, Gabon. It took him months to get there. His progress was slowed because he was jailed in a Cameroon prison for a customs infraction. (Borders never meant anything to Aronson.) Finally, on 26 April 1961, Aronson arrived in Lambaréné. For four months, he worked in the village and studied the New Testament with Schweitzer, who had written a pioneering book on Jesus more than fifty years earlier (The Quest of the Historical Jesus, 1906).

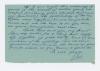

For the next decade, Aronson went from one area of crisis to another. Although he found it difficult to work within formal organizations, he worked in Gabon, Biafra, and Nigeria with the International Committee of the Red Cross and Terre des Hommes. Then in 1974 he saw on Dutch television that the Iraqis had dislocated 100,000 Kurdish civilians in a military offensive against those people. Shortly after, Aronson announced to his friends that he was going to Kurdistan to help the victims of this war. It was Aronson’s last journey. On 24 March 1975, he was arrested by the Iraqis somewhere in Kurdistan. There was a trial and a conviction. During his six months in prison, Aronson managed to have several messages smuggled from jail. One, dated 12 December 1975, reads: “Lately there haven’t been any executions. Vice President Saddam Hussein seems to be against capital punishment. I have good faith.” Within weeks, Aronson was dead.

For the next decade, Aronson went from one area of crisis to another. Although he found it difficult to work within formal organizations, he worked in Gabon, Biafra, and Nigeria with the International Committee of the Red Cross and Terre des Hommes. Then in 1974 he saw on Dutch television that the Iraqis had dislocated 100,000 Kurdish civilians in a military offensive against those people. Shortly after, Aronson announced to his friends that he was going to Kurdistan to help the victims of this war. It was Aronson’s last journey. On 24 March 1975, he was arrested by the Iraqis somewhere in Kurdistan. There was a trial and a conviction. During his six months in prison, Aronson managed to have several messages smuggled from jail. One, dated 12 December 1975, reads: “Lately there haven’t been any executions. Vice President Saddam Hussein seems to be against capital punishment. I have good faith.” Within weeks, Aronson was dead.

To Aronson, everything was possible. He rarely alluded to that time in his life when nothing was possible. With him, more than with many other people, his end was in his beginning. Bergen-Belsen was his first real school. It taught him to revere life, to disrespect laws, to question authority, and to challenge customs which seemed to stand in the way of the higher good as he understood it. All these strongly held beliefs may be seen in the Alex Aronson collection of letters and related material in the William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections. The core of the collection is the series of letters written by Aronson to Alan Mendelson, Professor of Religious Studies at McMaster.

Alan Mendelson, with co-editor Joan Michelson, published these letters (with slight revisions) in From Bergen-Belsen to Baghdad.

Mendelson, Alan, and Joan Michelson, eds. From Bergen-Belsen to Baghdad: the letters of Alex Aronson (Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press, 1992)