The Home Front in Rural Ontario: The Crombie Family Archives

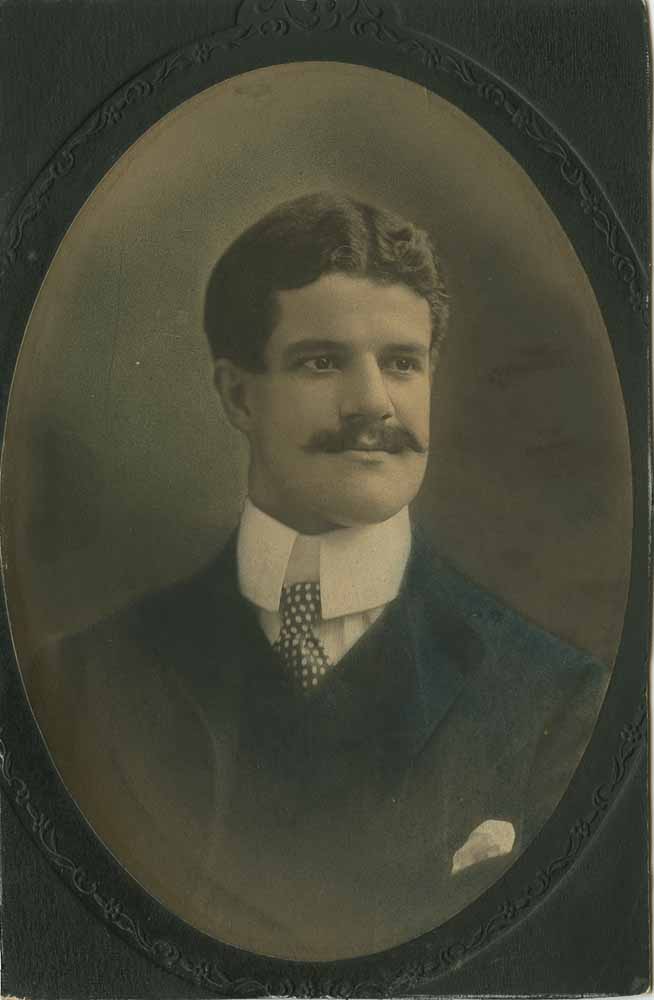

In 1911, just a few years prior to the outbreak of World War I, Edward Rubidge Crombie settled on Gilston Farm near Paris, Ontario. A former banker, Edward uprooted his young family and left the hustle and bustle of the city to seek a quieter and more satisfying life on the farm. Although he never regretted his decision, Edward struggled to balance his books and keep his family fed and occupied during the war years. To alleviate these stresses, he smoked “innumerable cigarettes” and wrote plays, poems and short stories. He read voraciously and meticulously recorded his life in a number of insightful diaries and newsletters. Through these documents Edward Crombie and his family come alive, affording readers a rare glimpse into life on the home front during the Great War.

In spite of the distance between Canada and Europe, the war had a significant impact on life at the Gilston Farm. In an impressive show of enthusiasm, thousands of young Canadians volunteered to fight overseas, resulting in a shortage of men in the home country. In 1916 Edward wrote: “it is extremely hard to get good help now-a-days with all the good men in khaki and the women and slackers earning easy money in the munitions factories.” Forced to do much of the heavy work himself, Edward appealed to his children by advertising in “The Daily Twitter” (+ p2), the family’s newsletter: “Wanted–Patriotic Kids to weed onions in a War Garden.” The war dragged on. Food shortages were common, and the Gilstonians felt it. The government instituted “wheatless” days, followed by “meatless” days, every Tuesday and Friday. In June 1918, Edward and his wife Hilda celebrated their twelfth wedding anniversary, prompting Edward to write about the fine roast Hilda had prepared, his “first taste of beef this year.” A newspaper clipping from the Toronto Daily Star, pasted into the family’s newsletter for 6 February 1918, is indicative of how deeply felt the shortages were: “In an effort to save fuel, the mills and factories throughout Ontario are to be closed from Friday morning until Tuesday next and all the stores, theatres etc. from Saturday to Tuesday.”

In spite of the distance between Canada and Europe, the war had a significant impact on life at the Gilston Farm. In an impressive show of enthusiasm, thousands of young Canadians volunteered to fight overseas, resulting in a shortage of men in the home country. In 1916 Edward wrote: “it is extremely hard to get good help now-a-days with all the good men in khaki and the women and slackers earning easy money in the munitions factories.” Forced to do much of the heavy work himself, Edward appealed to his children by advertising in “The Daily Twitter” (+ p2), the family’s newsletter: “Wanted–Patriotic Kids to weed onions in a War Garden.” The war dragged on. Food shortages were common, and the Gilstonians felt it. The government instituted “wheatless” days, followed by “meatless” days, every Tuesday and Friday. In June 1918, Edward and his wife Hilda celebrated their twelfth wedding anniversary, prompting Edward to write about the fine roast Hilda had prepared, his “first taste of beef this year.” A newspaper clipping from the Toronto Daily Star, pasted into the family’s newsletter for 6 February 1918, is indicative of how deeply felt the shortages were: “In an effort to save fuel, the mills and factories throughout Ontario are to be closed from Friday morning until Tuesday next and all the stores, theatres etc. from Saturday to Tuesday.”

The war hit home in May 1915 when the Crombies received news that a German submarine had sunk the ocean liner Lusitania. His half-brother, Frederick Sydney Hammond, and Kathleen, Frederick’s wife, were aboard the ship. Frederick was sailing to England to seek an officer’s commission, as he explains in a letter (+ p2). Telegrams arriving at Gilston provide a slow and agonizing description of the unfolding events. Kathleen was pulled from the water, but Frederick perished. The news disturbed Edward enormously and in later years, he was saddened by the fact no one commemorated or even remembered the tragic sinking of the Lusitania.

In 1914 Edward had himself applied for a commission to fight, but being forty years old, he was passed over for younger men like Frederick and another half brother, Herbert Renwick Hammond. At the beginning of the war, Herbert (aka Chub) lived with his young family in Victoria. He enlisted with the 15th Battery Sixth Artillery Brigade and saw active service in Belgium and France. He was twice wounded, once dangerously, and was awarded the Military Cross. After Frederick’s death, the family understandably became nervous about any news related to the war. Chub survived the war only to drown while on vacation in 1930. Edward's college friend, R.D. Whigham did join up. He sent Edward a letter (+ p2, p3) on 13 October 1916, written from West Africa where he was then stationed after being in the landing at Gallipoli and also in Egypt.

In 1914 Edward had himself applied for a commission to fight, but being forty years old, he was passed over for younger men like Frederick and another half brother, Herbert Renwick Hammond. At the beginning of the war, Herbert (aka Chub) lived with his young family in Victoria. He enlisted with the 15th Battery Sixth Artillery Brigade and saw active service in Belgium and France. He was twice wounded, once dangerously, and was awarded the Military Cross. After Frederick’s death, the family understandably became nervous about any news related to the war. Chub survived the war only to drown while on vacation in 1930. Edward's college friend, R.D. Whigham did join up. He sent Edward a letter (+ p2, p3) on 13 October 1916, written from West Africa where he was then stationed after being in the landing at Gallipoli and also in Egypt.

Although the war was not fought on Canadian soil, many ordinary citizens suffered deeply through those arduous years. The Crombie family archives, a rare treasure trove of valuable social history, offer an intimate perspective on a pivotal period through the eyes of an eloquent Canadian farmer.