McMaster University’s Own Soldier Poet: Bernard Trotter

In the fall of 1915, the British War Office contacted the University of Toronto for help in recruiting students for the officer corps of the British (Imperial) Army. One of the fifty young men who answered the call to service was Bernard Freeman Trotter, a twenty-five-year old graduate of McMaster University who was just beginning advanced studies at the University of Toronto. He left his studies and his family in Toronto in March 1916, and before the year was out, Trotter had successfully completed his training with both the Canadian and British armies in England, and was on his way to the Western Front as a junior officer with the Leicestershire 11th.

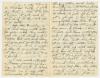

Trotter always had been a good correspondent; he continued to keep in contact with his family throughout his travels, his training and his travails. On Sunday afternoon, 6 May 1917, Trotter found time to complete another letter home. The following evening, a shell exploded close to the twenty-six-year old Assistant Transport Officer. He “dropped from his horse”, killed instantaneously. Bernard Trotter, like more than 60,000 other Canadians, never returned home from the Great War.

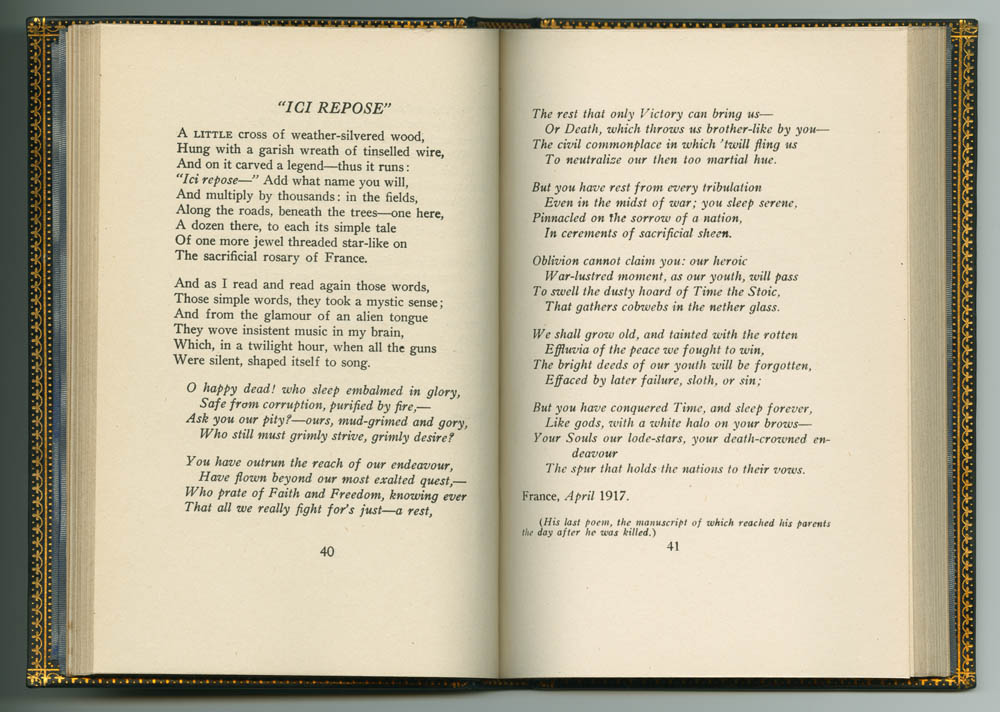

He was remembered. The young man's family and friends honoured his sacrifice by collecting and publishing his poetry. Although Trotter complained that his poetic muse could not “flourish among the interruptions and lack of privacy of military life”, the best of the poems which appear in A Canadian Twilight and Other Poems of War and of Peace, were written overseas, and established his reputation as one of Canada’s war poets. In “Ici Repose”, a “pome” attached to one of the letters that arrived home after his death, Trotter paid tribute to the dead, and expressed his hopes and fears for the future peace. He imagined himself a survivor, addressing the war dead:

We shall grow old, and tainted with the rotten

Effluvia of the peace we fought to win,

The bright deeds of our youth will be forgotten,

Effaced by later failure, sloth, or sin;

But you have conquered Time, and sleep forever,

Like gods, with a white halo on your brows --

Your souls our lode-stars, your death crowned endeavour

The spur that holds the nations to their vows.

Trotter and his family left us more than poetry. The family preserved a remarkable collection of his letters and other papers, including texts and notebooks from his training as an officer, as well as other family correspondence, which the Division of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster University is now fortunate enough to hold.

Through the letters in this collection, we can catch glimpses of Bernard Trotter’s early life, and then follow his military “luck.” He was lucky to claim a sleeping car on the long train ride to Halifax, lucky to be assigned a first class berth on the ship, lucky to see the English countryside so often described to him by his father, lucky to attend Oxford for his final training as a British officer, and lucky, or so he felt, not to have to wait too many months for the call to the Front. Lucky too, at the Front, where he was assigned to a barn with “real beds”, had a manservant to clean the mud from his uniform every day, and was selected to leave the Front to train as a Transport Officer, missing the bloody battle of Arras early in April 1917. He loved working transport, he explained to his family, for “I find shell fire far less trying on the nerves when on horseback in charge of a convoy than when crouching in a trench.”

Through the letters in this collection, we can catch glimpses of Bernard Trotter’s early life, and then follow his military “luck.” He was lucky to claim a sleeping car on the long train ride to Halifax, lucky to be assigned a first class berth on the ship, lucky to see the English countryside so often described to him by his father, lucky to attend Oxford for his final training as a British officer, and lucky, or so he felt, not to have to wait too many months for the call to the Front. Lucky too, at the Front, where he was assigned to a barn with “real beds”, had a manservant to clean the mud from his uniform every day, and was selected to leave the Front to train as a Transport Officer, missing the bloody battle of Arras early in April 1917. He loved working transport, he explained to his family, for “I find shell fire far less trying on the nerves when on horseback in charge of a convoy than when crouching in a trench.”

All of this talk of “luck”, of course, tells us a lot about the nature of soldiers’ letters home. Their correspondence was routinely censored (and since Trotter sometimes was assigned to censor letters, he knew this very well). Soldiers writing home probably were less concerned with official censors than with protecting their families back home and preserving their own sanity. “It won’t do you any good to worry when you see the Leicesters mentioned in the fighting news,” Trotter assured his family in March 1917, “There are ten battalions somewhere in I should think at least half as many different divisions, which may be anywhere; so when you see the name the chances are strongly in favor of its having nothing to do with me.”

So what can these letters tell us? Trotter lets us glimpse life at the Front. “One is inclined, I am afraid, to lose perspective very badly, and give no thought to what happens to anyone save your own little party,” he thoughtfully explained. “You watch shells bursting over other people’s areas with the most perfect equanimity. As for the poor Bosch, who gets regularly at least ten to one, he is entirely beyond the pale of sympathy except at odd and fleeting moments.”

So what can these letters tell us? Trotter lets us glimpse life at the Front. “One is inclined, I am afraid, to lose perspective very badly, and give no thought to what happens to anyone save your own little party,” he thoughtfully explained. “You watch shells bursting over other people’s areas with the most perfect equanimity. As for the poor Bosch, who gets regularly at least ten to one, he is entirely beyond the pale of sympathy except at odd and fleeting moments.”

Beyond these scattered insights, these letters allow us to share the experience of those at home, who only saw the war through newspaper accounts and letters from those who served. Historian Jeffrey Keshen argues that such letters left those at home little prepared for the damaged men and women who did return from the war. Perhaps. But in Trotter’s letters we can see reflected a family who sensed the horror of the war, were anxious for personal news, and who feared the worst.

And because the collection includes other correspondence, we can experience the impact of 'the worst'. We can read the official reports of Trotter’s commanding officer and company padre, delivered to the family several weeks later. We can read the letters from Trotter’s sisters and mother to Bernard’s brother, historian Reginald Trotter, relaying the bad news, describing the reactions of friends and neighbours, planning memorials and the book of poetry as a tribute. And we can see their careful efforts to conceal Bernard’s death, for nearly a month, from his father, then hospitalized with prostate cancer.

In her letter to Reginald, Bernard’s mother wrote: “I have some other news for you though that is sad and hard though not so sad or hard as it might have been. Bernard was killed in action last Monday. He would have chosen that, I think, rather than being sick and invalided home, or taken prisoner, or worse than anything, horribly mutilated as so many poor fellows have been.” In death, as in life, Bernard Trotter was “lucky”. He would not “grow old, and tainted with the rotten effluvia of the peace” he had bravely “fought to win.”

Keshen, Jeffrey A. Propaganda and Censorship During Canada’s Great War (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1996)

Trotter, Bernard Freeman. A Canadian Twilight and Other Poems of War and Peace (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1917)