Tools for Peace, a “Made in Canada” Peace Movement

Following the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua in July 1979, a dynamic grass roots movement emerged in Canada in support of the Nicaraguan people. Out of this solidarity movement evolved a nation-wide campaign called Tools for Peace. Throughout the 1980s, Tools for Peace’s annual collection of material aid became a rallying point for thousands of Canadians from all walks of life who wanted to support the Nicaraguan people, and express their opposition to the U.S.’s economic blockade and military intervention.

The event that catalyzed the birth of Tools for Peace was the 1981 solidarity tour to Nicaragua by unionists, fishermen, church and community activists from the Lower Mainland of British Columbia. While in Nicaragua, tour members were deeply moved by the desperate situation of the Nicaraguan people. One member of this solidarity tour recalled the feelings of hope they witnessed in the country among those who were rebuilding their country after decades of the Somoza dictatorship:

The event that catalyzed the birth of Tools for Peace was the 1981 solidarity tour to Nicaragua by unionists, fishermen, church and community activists from the Lower Mainland of British Columbia. While in Nicaragua, tour members were deeply moved by the desperate situation of the Nicaraguan people. One member of this solidarity tour recalled the feelings of hope they witnessed in the country among those who were rebuilding their country after decades of the Somoza dictatorship:

The future looked so hopeful. There was a great burst of culture and songs and enthusiasm for literacy – and all these new health care programs. Everybody was “up.” The enthusiasm! We got swept up in it. I remember us saying, “What are we going to do when we go home? There must be something we can do.” There were so many shortages, so many factories and buildings were destroyed, so many people who were maimed, we felt that there must be some way that we, as Canadians, could make some partnership with these people. And that’s when we talked about what we could do.

The energetic educational work carried out by the tour members after they returned home resulted in the collection of $25,000 aid in the form of “tools for peace”: fishing equipment, carpentry tools, saws, hammers, agricultural tools, day care supplies and other basic equipment which was sent to Nicaragua in the fall of 1981 aboard a ship, the Monimbo. When activists from other parts of B.C. heard about the shipment, they immediately set about collecting another $70,000 in aid which was sent in December aboard a Greek frigate, the Andros Mentor.

As news of the boatloads of aid spread, a third shipment, christened the “Monimbo project,” because of the promised return of the Monimbo, was planned. This time, hundreds of individuals, solidarity groups, union, community, church, and women’s organizations, as well as non-governmental agencies and institutions from across Canada were galvanized into action. Although the Monimbo itself never returned, the idea of a “Nicaraguan Boat Project” so ignited the imaginations of solidarity activists, there was no turning back. For the next ten years, increasingly large quantities of aid were raised in towns and cities across Canada, then sent by truck and rail to Vancouver, and shipped to the port of Corinto in Nicaragua.

As news of the boatloads of aid spread, a third shipment, christened the “Monimbo project,” because of the promised return of the Monimbo, was planned. This time, hundreds of individuals, solidarity groups, union, community, church, and women’s organizations, as well as non-governmental agencies and institutions from across Canada were galvanized into action. Although the Monimbo itself never returned, the idea of a “Nicaraguan Boat Project” so ignited the imaginations of solidarity activists, there was no turning back. For the next ten years, increasingly large quantities of aid were raised in towns and cities across Canada, then sent by truck and rail to Vancouver, and shipped to the port of Corinto in Nicaragua.

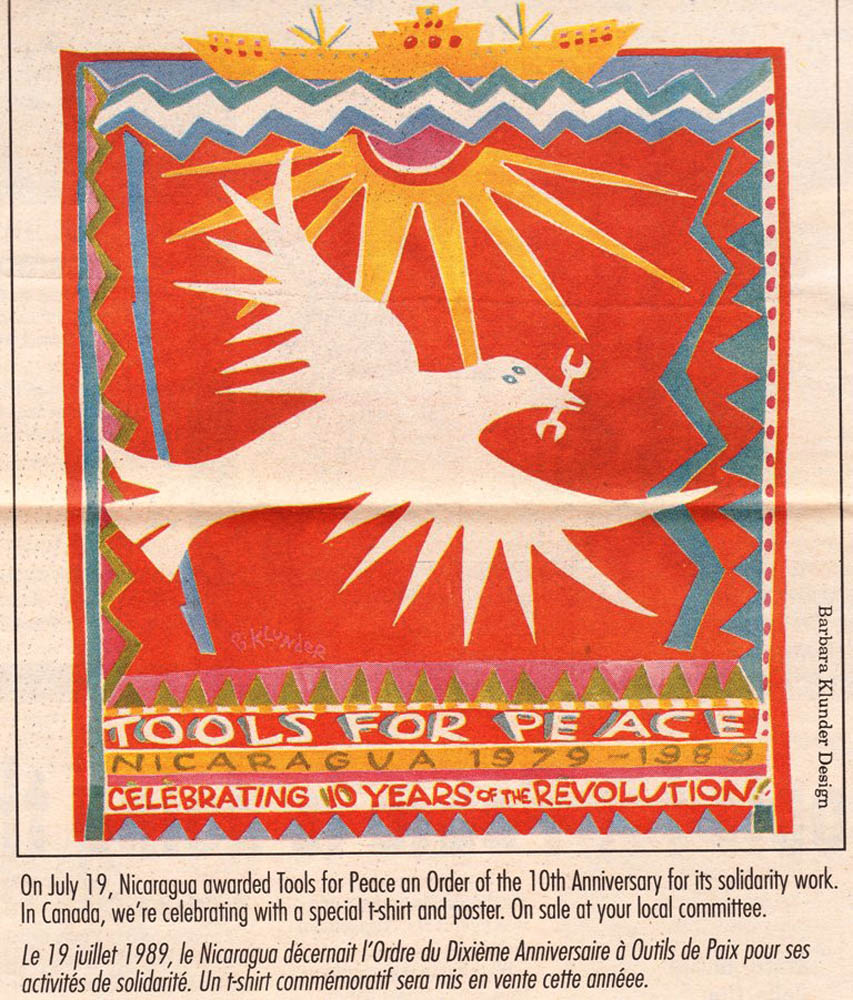

By 1985, $3 million dollars in aid had been collected and the number of Tools for Peace committees had grown to sixty. Tools for Peace had become a vast solidarity operation, raising more than a million dollars in aid each year, coordinated through a National Office in Vancouver, a Public Affairs and Education Office in Toronto, and a Tools for Peace office in Managua. The movement became an effective lever for pressuring the Canadian government to provide more generous development aid to Nicaragua and to more energetically apply its diplomatic influence to end U.S. intervention.

One factor that strengthened the campaign, at a time when many felt alienated by the politics of the Left, was the openness of Tools for Peace to anyone who wished to participate. Tools for Peace had a task for everyone. And it welcomed anyone who wanted to “do something” for the Nicaraguan people. Its richness as an experiment in solidarity came not from any central point of control, but rather from its varied manifestations as expressed by each committee, each community and each region. Beyond the campaign’s nationally-set political goals and the basic infrastructure required to run a national campaign, Tools for Peace’s activities were, for the most part, defined at the local level, by local people.

The very practical nature of collecting and organizing material aid acted as a “glue” to hold together a veritable sea of personalities, political agendas and regional tensions, without which the campaign would almost certainly have foundered. People set aside their differences in order to attend to the endless tasks of gathering medical supplies, building wooden crates, distributing posters, finding warehousing, preparing packing slips, arranging trucking, soliciting union support, organizing music concerts, writing letters of thanks, translating labels and preparing bills of lading.

The defeat of the Sandinistas in the 1990 Nicaraguan elections came as a major blow to Tools for Peace and its volunteers gradually shifted their focus to other peace and social justice causes. The national offices of Tools for Peace in Vancouver and Toronto closed in 1991 followed by the Managua office in 1992.

Tools for Peace was emulated by organizations around the world, and applauded by the Nicaraguan government as a model of people-to-people solidarity. However, while others attempted to replicate the Canadian Tools for Peace model, no other group was able to emulate its scale or singular success. Tools for Peace has become the stuff of solidarity legend, a movement which ignited the passions of a generation of Canadian activists.