Youth Mobilize for Peace: The Canadian Youth Congress in the 1930s

For many of us, the terms “young people” and “peace movement” bring to mind the 1960s and early 1970s and the protests against American participation in the Vietnam War. Few of us know that thirty years earlier, there was another youth-led peace movement that was eventually overshadowed by the Second World War. In the midst of the bleakness of the 1930s—the collapse of the capitalist economy, the rise of fascism, and the growing threat of war—optimistic youth made an impressive stand for peace.

In Canada, these hopeful efforts would come to be coordinated by the Canadian Youth Congress (CYC), an umbrella group for most of the country’s youth organizations. The impetus for establishing the CYC was not the threat of war but rather the economic hardship that challenged youth coming of age during the Great Depression. The future looked daunting in the face of high unemployment and the failure of governments to do anything about it. In response to this situation, a small group of young men and women came together in Toronto in May 1935 to establish the CYC. One of the chief roles of the Congress was to lobby governments to initiate change, and to mobilize youth organizations to take part in this lobbying. In a very short time, CYC offices sprang up across the country. At its height in the late 1930s, the CYC had a constituent membership of four hundred thousand, attracted over seven hundred participants to its annual national congresses, and sent large delegations to international youth congresses held in Geneva in 1936 and New York State in 1938. Its membership was also unusually diverse; after the Ottawa Congress of 1936, the CYC reported that it represented “men and women: youth from all the different religious denominations; from schools and universities; from the Y.M. and W.C.A.’s; from all political groupings; from different racial groups; from farms, factories, the professions; peace, cultural, athletic societies—English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians. The congress expressed the thought of awakened and intelligent youth opinion throughout our country” (Youth’s Peace Policy, 1936).

In Canada, these hopeful efforts would come to be coordinated by the Canadian Youth Congress (CYC), an umbrella group for most of the country’s youth organizations. The impetus for establishing the CYC was not the threat of war but rather the economic hardship that challenged youth coming of age during the Great Depression. The future looked daunting in the face of high unemployment and the failure of governments to do anything about it. In response to this situation, a small group of young men and women came together in Toronto in May 1935 to establish the CYC. One of the chief roles of the Congress was to lobby governments to initiate change, and to mobilize youth organizations to take part in this lobbying. In a very short time, CYC offices sprang up across the country. At its height in the late 1930s, the CYC had a constituent membership of four hundred thousand, attracted over seven hundred participants to its annual national congresses, and sent large delegations to international youth congresses held in Geneva in 1936 and New York State in 1938. Its membership was also unusually diverse; after the Ottawa Congress of 1936, the CYC reported that it represented “men and women: youth from all the different religious denominations; from schools and universities; from the Y.M. and W.C.A.’s; from all political groupings; from different racial groups; from farms, factories, the professions; peace, cultural, athletic societies—English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians. The congress expressed the thought of awakened and intelligent youth opinion throughout our country” (Youth’s Peace Policy, 1936).

While a broad spectrum of ideas and opinions was always expressed at CYC annual congresses, the CYC—in its public statements—consistently stood for peace and viewed war was as a threat to economic and social stability. Indeed, the possibility of another global war seemed all too real. In 1935, the year of the CYC’s founding, Italy had invaded Ethiopia; in 1936, the year of the CYC’s first national congress in Ottawa, Germany invaded the Rhineland and signed pacts with Italy and Japan; soon after the Ottawa Congress ended, the Spanish Civil War began. In response to national and international events, the 1936 Ottawa Congress produced the Declaration of the Rights of Youth which called for youth employment training, improved health care, recreational and educational facilities, and, last but not least, world peace. By the end of the year, the CYC released its Youth’s Peace Policy. The policy boldly declared that “war is not inevitable” and that “lasting peace can only be organized on a basis of justice. Moreover, force must be placed at the service of justice.” The CYC also supported the much maligned League of Nations: “it is not the League which has failed, but rather that governments have failed to fulfill their obligations under the Covenant.” The policy also contained a message for the Canadian government, stating that “Canada should determine its own participation in war in all cases” and not simply blindly follow the lead of Britain. Finally, the CYC demanded that the “Canadian Government immediately sever all financial and diplomatic relations with the aggressor.”

While a broad spectrum of ideas and opinions was always expressed at CYC annual congresses, the CYC—in its public statements—consistently stood for peace and viewed war was as a threat to economic and social stability. Indeed, the possibility of another global war seemed all too real. In 1935, the year of the CYC’s founding, Italy had invaded Ethiopia; in 1936, the year of the CYC’s first national congress in Ottawa, Germany invaded the Rhineland and signed pacts with Italy and Japan; soon after the Ottawa Congress ended, the Spanish Civil War began. In response to national and international events, the 1936 Ottawa Congress produced the Declaration of the Rights of Youth which called for youth employment training, improved health care, recreational and educational facilities, and, last but not least, world peace. By the end of the year, the CYC released its Youth’s Peace Policy. The policy boldly declared that “war is not inevitable” and that “lasting peace can only be organized on a basis of justice. Moreover, force must be placed at the service of justice.” The CYC also supported the much maligned League of Nations: “it is not the League which has failed, but rather that governments have failed to fulfill their obligations under the Covenant.” The policy also contained a message for the Canadian government, stating that “Canada should determine its own participation in war in all cases” and not simply blindly follow the lead of Britain. Finally, the CYC demanded that the “Canadian Government immediately sever all financial and diplomatic relations with the aggressor.”

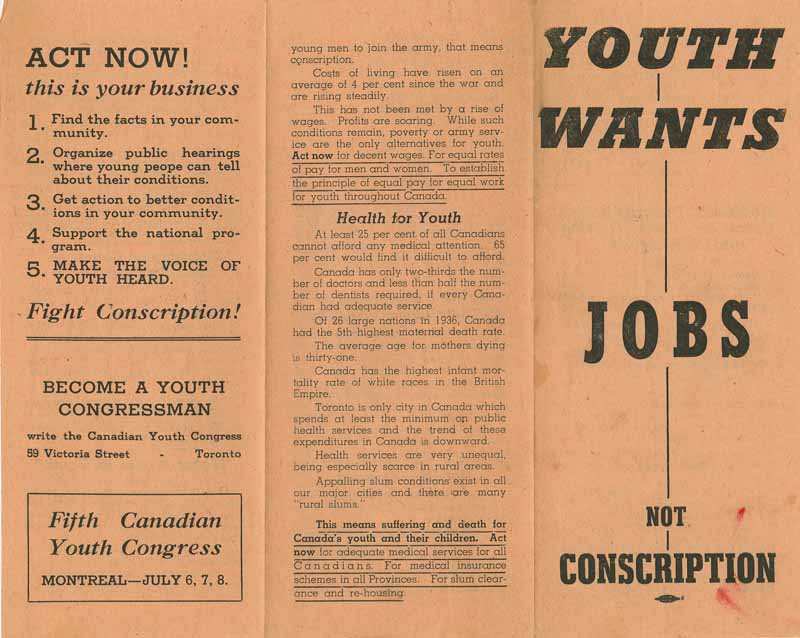

Even after war finally broke out in 1939, the CYC continued to take stands that sometimes conflicted with popular opinion. The fifth annual Congress, held in Montreal in 1940, supported civil liberties, stating that “the War Measures Act and the Defence of Canada Regulations deny our traditional rights of free speech, free assembly, organization and trade union action, free press, radio and pulpit.” The Congress also spoke out against conscription, stating in Youth Wants Jobs Not Conscription that conscription of youth “threatens to be the alternative to improved conditions and a chance to make a living,” and viewing perennially low wages as a means of forcing young men to join the army.

While these positions may seem progressive from today’s perspective, at the time they were perceived by many people to be naively unpatriotic and perhaps even subversive. Largely because of the presence of Communists among the CYC membership, the organization had been under surveillance by the RCMP nearly from its inception. After the war broke out, the RCMP wanted the Canadian government to declare the CYC illegal. While this did not happen, several CYC constituent groups were banned, including the Young Communist League.

The CYC began to experience other fractures. There was an internal conflict between those who supported the war effort, those who opposed it, and those who were undecided. After the 1940 Congress, some groups withdrew their membership in the CYC because of the Congress’s failure to strongly support Canadian involvement in the war. Ironically, the diversity of the CYC’s membership, originally one of its strengths, now appeared to be its greatest weakness. The organization that had welcomed as guest speakers and mentors such dissimilar men as Tommy Douglas of the CCF, Denton Massey of the Conservative party, and Liberal Paul Martin Snr., could not withstand the pressures brought about by the war. In 1942 the CCY disbanded. By this time, many of its former members were serving overseas. Sadly, some of those who had stood for peace were killed in the very war they had opposed.

Axelrod, Paul. “The Student Movement of the 1930s”, in Paul Axelrod and John G. Reid, eds.,Youth, University and Canadian Society (Kingston and Montreal, 1989), pp. 216-245.

Latta, Ruth. They Tried: the Story of the Canadian Youth Congress (Ottawa: R. Latta, 2006)