Young Canadian Brothers in England: “Even here it is hard to realize there is a war on”

Fresh with enthusiasm to accomplish his part in the war, Aircraftman (AC) Francis J. “Wit” McDaniel arrived at Hastings, England in May 1942 to await posting as an erk (aircraft maintenance crewman). He was not uninformed about the nature of his imminent service. His elder brother Leading Aircraftman (LAC) Bernard M. “Bain” McDaniel, a member of the ground crew of No. 408 (Goose) Squadron since December 1941, had already written to give him a clear sense of what to expect from the wartime England – pretty countryside, a lack of good tobacco products, and, with “about 4 women to a man,” plenty of opportunities to improve his dancing abilities. And he was not to be disappointed.

Before embarking, Wit had studied at the Technical Training School at St. Thomas, Ontario, as Bain had also done, leaving their family in Regina, Saskatchewan. Their father, Capt. Bernard J. McDaniel, KC, a veteran of the First World War, had been born in Margaree, Nova Scotia, later settling in the West. He was a lawyer and, after a provincial by-election in 1938, Member of the Legislative Assembly for Regina City. Occasionally the regular, almost weekly letters sent by both men during the war provide glimpses into their family’s life at home in Regina, including thoughts on their father’s loss in the provincial election of 1944.

It was, of course, the brothers’ own experiences overseas which dominated the pages of their letters. Though Bain and Wit served with the RCAF, supporting bomber and fighter squadrons respectively, their correspondence provides few details of the war. Located in northern England and lacking an immediate connection with the battles at the front, Wit wrote to his parents in May 1943 that “even here it is hard to realize there is a war on …” The German raids of the Battle of Britain were long over; only once in his years overseas, spent mostly with No. 409 (Nighthawk) squadron, did Wit hear any German bombs, even in the distance, and Bain heard none at all. When Wit and Bain wrote about the war directly, their letters often reveal the same attitude that others far from the events must have had: hopefulness for the Russian front and sympathy for the tremendous losses there and anticipation for an Allied invasion of Hitler’s Europe after the trial run at Dieppe. The McDaniels’ dominant and most intimate experience of war consisted not of battles or bombardments but rather of the routine grind of a regular job in a foreign land, a job made necessary by aero-mechanized warfare.

It was, of course, the brothers’ own experiences overseas which dominated the pages of their letters. Though Bain and Wit served with the RCAF, supporting bomber and fighter squadrons respectively, their correspondence provides few details of the war. Located in northern England and lacking an immediate connection with the battles at the front, Wit wrote to his parents in May 1943 that “even here it is hard to realize there is a war on …” The German raids of the Battle of Britain were long over; only once in his years overseas, spent mostly with No. 409 (Nighthawk) squadron, did Wit hear any German bombs, even in the distance, and Bain heard none at all. When Wit and Bain wrote about the war directly, their letters often reveal the same attitude that others far from the events must have had: hopefulness for the Russian front and sympathy for the tremendous losses there and anticipation for an Allied invasion of Hitler’s Europe after the trial run at Dieppe. The McDaniels’ dominant and most intimate experience of war consisted not of battles or bombardments but rather of the routine grind of a regular job in a foreign land, a job made necessary by aero-mechanized warfare.

The military nature of the work itself was at first something novel. The brothers could not be too descriptive of operations at the base, of course, for reasons of secrecy, but the McDaniels must have shared a sense of camaraderie with the flight crews and an interest in their exploits. Bain suggested this when he quickly ended a letter home (24 July 1943): “Well folks that is about all for the present – I want to watch a take off – they are on there [sic] way to the enemy ground and I hear the engine warming up now.” Bain wrote more about military life than did his brother Wit, perhaps on account of an aversion or frustration on the younger man’s part. Having been decorated with the commonly awarded Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Maple Leaf, Wit renamed it the Royal Order of Spam and announced with youthful idealism to his parents: “personally I don’t believe in decoration of any kind.”

In general, the work became stale, the frustrations increased, and any variations in the daily routine were much appreciated and duly noted in the letters home. The McDaniel brothers filled their free time on passes and leaves by making many dutiful family visits: to their mother Beatrice’s impressively active though aged mother and their aunts in Kent, especially early on. The brothers were quite close, and when not visiting family they tried to coordinate passes and leaves in order to reconnect with each other and with old friends from Saskatchewan serving in England and Europe, including “Pearly” Gaetz, Clyde McDougal, Bernie Heintz, and Jack Forsyth. In the summer of 1944 Wit transferred into Bain’s squadron, further solidifying the brothers’ connection to each other while overseas. Such leisure time was initially most often spent in search of dances, shows at the cinema and theatre, and often the company of women with whom to share the experience. Time was also spent in the quest for elusively scarce provisions: lighters, cigarettes, chocolate, and other little luxuries for themselves or for their seemingly destitute Kentish relatives. Often simply visiting a nice city, town or rural spot would provide sufficient distraction while on leave; an evening of rabbit shooting on an estate in Angus, Scotland, gave Bain something to do and to report home.

In general, the work became stale, the frustrations increased, and any variations in the daily routine were much appreciated and duly noted in the letters home. The McDaniel brothers filled their free time on passes and leaves by making many dutiful family visits: to their mother Beatrice’s impressively active though aged mother and their aunts in Kent, especially early on. The brothers were quite close, and when not visiting family they tried to coordinate passes and leaves in order to reconnect with each other and with old friends from Saskatchewan serving in England and Europe, including “Pearly” Gaetz, Clyde McDougal, Bernie Heintz, and Jack Forsyth. In the summer of 1944 Wit transferred into Bain’s squadron, further solidifying the brothers’ connection to each other while overseas. Such leisure time was initially most often spent in search of dances, shows at the cinema and theatre, and often the company of women with whom to share the experience. Time was also spent in the quest for elusively scarce provisions: lighters, cigarettes, chocolate, and other little luxuries for themselves or for their seemingly destitute Kentish relatives. Often simply visiting a nice city, town or rural spot would provide sufficient distraction while on leave; an evening of rabbit shooting on an estate in Angus, Scotland, gave Bain something to do and to report home.

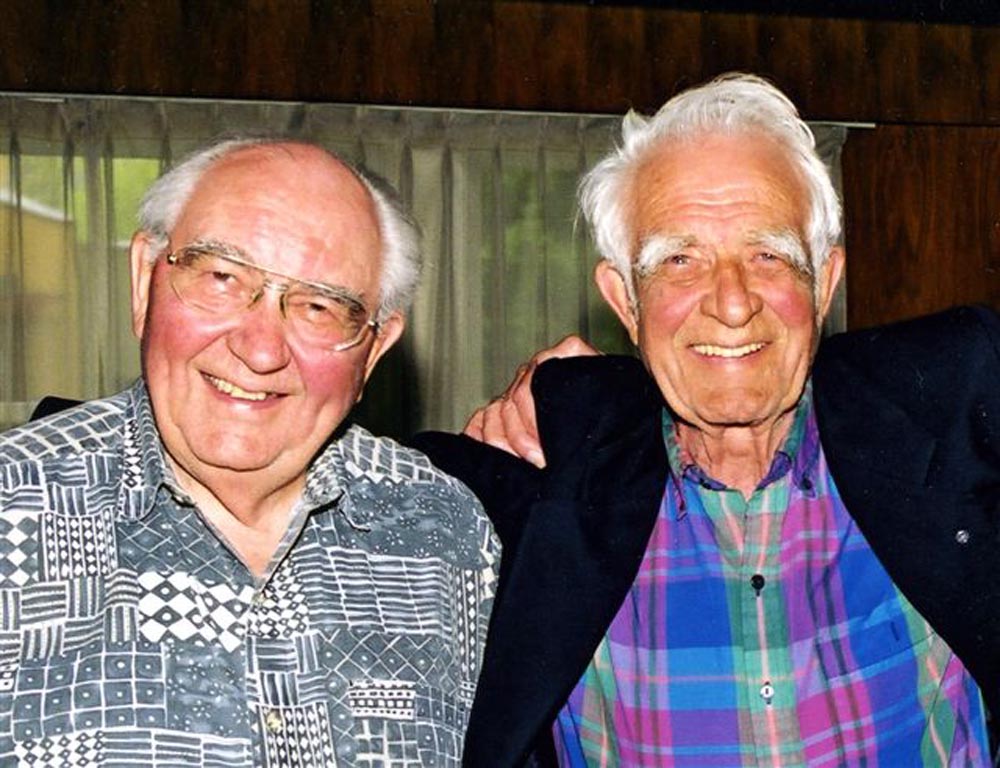

Bain returned to Canada as a corporal with a new Scottish wife Gwen Murray soon after Christmas 1944, and Wit, who had reached the rank of LAC, followed in the summer of 1945. Their years with the RCAF in England had changed them significantly, these changes being inscribed in a wonderful collection of over 120 letters from brothers Bernard and Francis McDaniel, supplemented with other contemporary family letters and documents.

Moyes, Philip J.R. Bomber Squadrons of the R.A.F. and their Aircraft (London: Macdonald and Co., 1964)

Pletsch, Mary. "The Guardian Angels of this Flying Business: RCAF Ground Crew in 6 Group", 2002 dissertation, RMC.