Alan Crawley and Contemporary Verse

Tim McIntyre, Queen’s University

Far from the cultural centres of the east, Alan Crawley and Contemporary Verse helped spur Canadian poetry's “Renaissance of the Forties” as one of the few modern Canadian poetry magazines of the time. In the early forties, conventional romanticism was on the wane, and a more modern poetry, with realistic imagery and the words and rhythms of natural speech, was burgeoning. Nevertheless, few small literary magazines existed, which made it difficult for new or experimental writers to find publication. In Victoria, BC, in 1941, West-coast poets Dorothy Livesay and Floris McLaren, with help from Doris Ferne and Anne Marriott, decided to  start a modern poetry magazine and asked Alan Crawley to be its editor. Crawley, too, saw the need for a magazine for new and modern Canadian poets. He accepted the job, despite the fact that the slim market for poetry, the ongoing world war, and Crawley's blindness posed significant obstacles to its long-term success.

start a modern poetry magazine and asked Alan Crawley to be its editor. Crawley, too, saw the need for a magazine for new and modern Canadian poets. He accepted the job, despite the fact that the slim market for poetry, the ongoing world war, and Crawley's blindness posed significant obstacles to its long-term success.

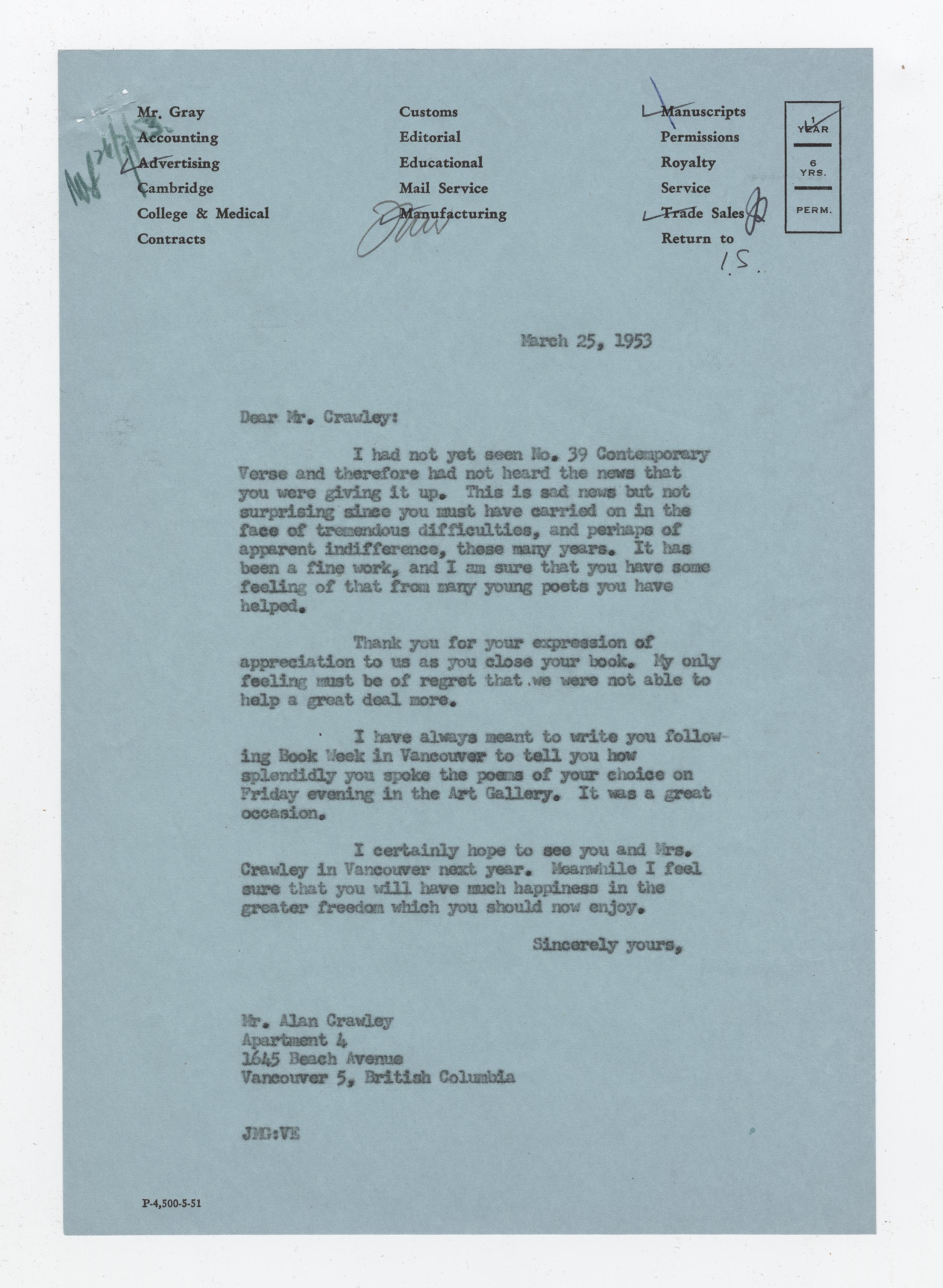

McLaren, CV's business manager, describes the production of the first issue: “100 copies of a sixteen page booklet could be mimeographed for $16 ... With the cost of promotion letters, envelopes and postage, $25 dollars would bring out the first issue; one hundred subscribers at $1.00 each would carry the magazine for the first year.” In late September 1941, 100 copies of CV 1 were produced, and 75 were mailed to subscribers in early October. By 1947, according Floris McLaren's letter soliciting advertising from Oxford University Press, CV had “a paid up circulation of more than two hundred with approximately another fifty copies going out as review, exchange, etc.” and with “more than twenty subscriptions ... to public and college libraries, [and] another [sic] large percentage to teachers in high schools and universities.” By 1952, in another attempt to sell advertising space, McLaren could tell Oxford UP that circulation had grown to “just under four hundred.”

In Alan Crawley and Contemporary Verse, Joan McCullagh argues that although “the development of modern poetry in Canada is usually presented as an eastern and, even more specifically, a Montreal  accomplishment,” Crawley and CV were vital to the development of modern poetry in Canada, thanks to the high standards set by CV and Crawley's personal involvement with many of the period's major poets. As sole editor, Crawley was responsible for what would appear in CV, and his personal dynamism was paramount to the magazine's success. Rather than sending standard rejection slips, Crawley commented on and returned manuscripts in what was not only “an enormous amount of work” but also “a valuable service to poets who came to rely on Crawley's astute, impartial judgement”, as McCullagh observes.

accomplishment,” Crawley and CV were vital to the development of modern poetry in Canada, thanks to the high standards set by CV and Crawley's personal involvement with many of the period's major poets. As sole editor, Crawley was responsible for what would appear in CV, and his personal dynamism was paramount to the magazine's success. Rather than sending standard rejection slips, Crawley commented on and returned manuscripts in what was not only “an enormous amount of work” but also “a valuable service to poets who came to rely on Crawley's astute, impartial judgement”, as McCullagh observes.

The material in Crawley’s papers at the Queen's University Archives sheds light on Crawley's work as an editor. Correspondence between Crawley and poets like Earle Birney and Anne Wilkinson gives some insight into how particular poems and issues took shape under Crawley's editorship: two of Birney's letters, for example, detail his intention and technique behind “Man on a Tractor,” while Jay MacPherson's file includes original submissions of several of her poems, such as “Metamorphosis” and “The Third Eye."

The letters in this archive also demonstrate the tremendous support Crawley gave to poets like MacPherson, P.K. Page, and James Reaney, early in their careers. Page offers one of the most articulate expressions of appreciation for Crawley’s editorial guidance: “You've no idea what a stimulating thing it has been – this contact with you, even across so many miles. It is doubly good to get praise from someone who is unafraid to damn.” Perhaps the best indication of the reverence Canada's poetry community had for the magazine, however, is seen in responses to the news of its discontinuation. After Crawley's foreword to the 1951 anniversary issue of CV, which expressed some doubt about the magazine's ability to continue, a group of Montreal poets, including A.M. Klein, Louis Dudek, and F.R. Scott, sent a telegram to make their feelings known, telling Crawley “Montreal poets meeting tonight are convinced survival Contemporary Verse essential to Canadian literature.”

The letters in this archive also demonstrate the tremendous support Crawley gave to poets like MacPherson, P.K. Page, and James Reaney, early in their careers. Page offers one of the most articulate expressions of appreciation for Crawley’s editorial guidance: “You've no idea what a stimulating thing it has been – this contact with you, even across so many miles. It is doubly good to get praise from someone who is unafraid to damn.” Perhaps the best indication of the reverence Canada's poetry community had for the magazine, however, is seen in responses to the news of its discontinuation. After Crawley's foreword to the 1951 anniversary issue of CV, which expressed some doubt about the magazine's ability to continue, a group of Montreal poets, including A.M. Klein, Louis Dudek, and F.R. Scott, sent a telegram to make their feelings known, telling Crawley “Montreal poets meeting tonight are convinced survival Contemporary Verse essential to Canadian literature.”

By the early 1950s, CV faced significant difficulties. The financial state of the magazine – always precarious because CV was unsubsidized – gave cause for concern. As McLaren wrote in the Tamarack Review, “Printing costs had risen to nearly $100 an issue, and our rigidly restricted budget had never allowed the hoped for change from mimeograph to printing,” except for printed covers. Neither could they begin to pay contributors or expand the magazine's scope or circulation. CV's “three hundred $1.00 subscriptions no longer covered costs and only occasional unexpected gifts prevented an annual deficit.” Even additional funding would not wholly solve CV's difficulties, because without finding some “energetic assistants,” “any increase in the work of correspondence, promotion, or even distribution of an enlarged subscription list seemed impossible.” Perhaps more importantly, Crawley seemed to be losing enthusiasm for the work. He felt that CV was

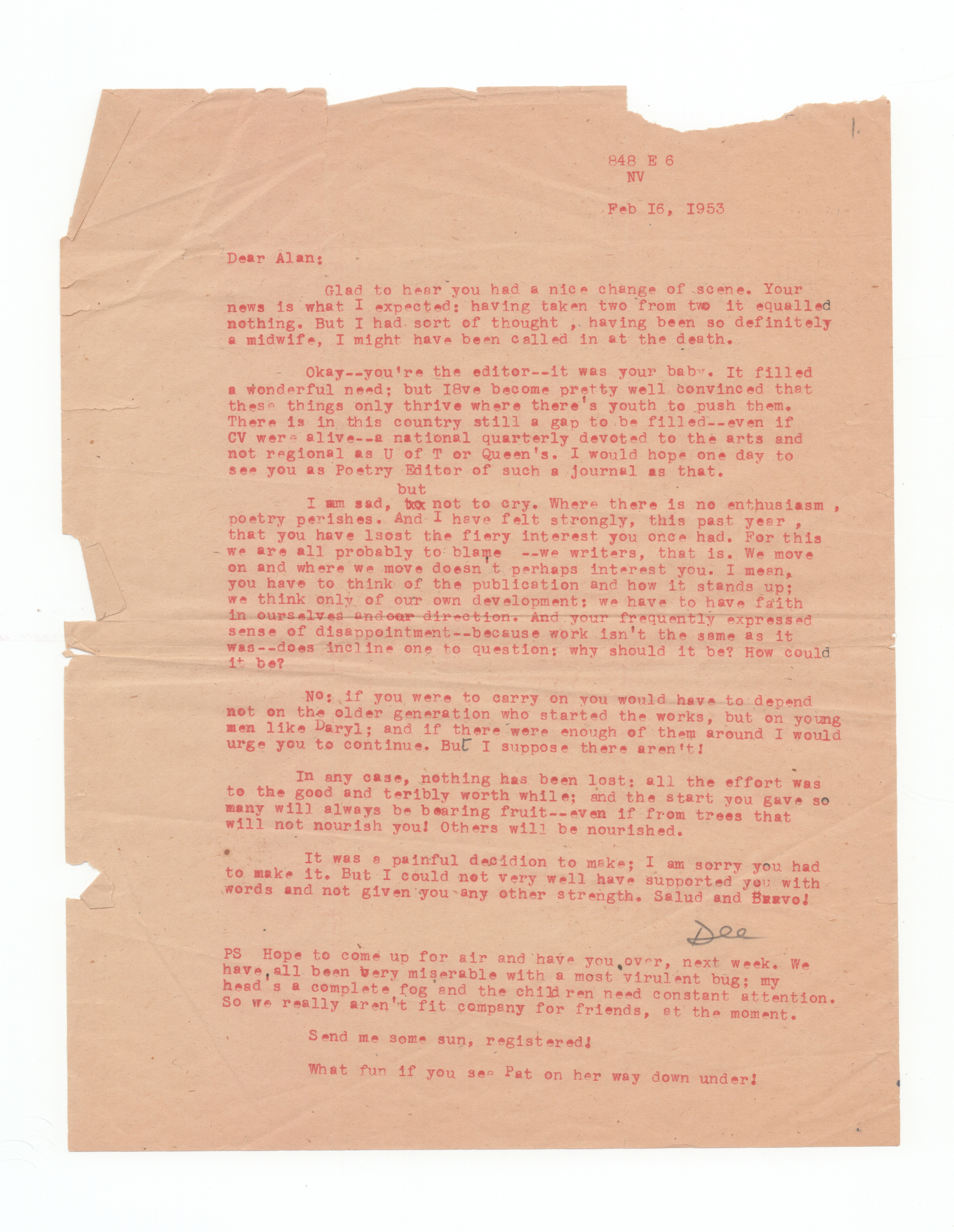

By the early 1950s, CV faced significant difficulties. The financial state of the magazine – always precarious because CV was unsubsidized – gave cause for concern. As McLaren wrote in the Tamarack Review, “Printing costs had risen to nearly $100 an issue, and our rigidly restricted budget had never allowed the hoped for change from mimeograph to printing,” except for printed covers. Neither could they begin to pay contributors or expand the magazine's scope or circulation. CV's “three hundred $1.00 subscriptions no longer covered costs and only occasional unexpected gifts prevented an annual deficit.” Even additional funding would not wholly solve CV's difficulties, because without finding some “energetic assistants,” “any increase in the work of correspondence, promotion, or even distribution of an enlarged subscription list seemed impossible.” Perhaps more importantly, Crawley seemed to be losing enthusiasm for the work. He felt that CV was  not attracting enough quality manuscripts and that, in McCullagh's words, “Canadian poetry was moving in a direction he was not in step with.” In February 1953, CV published its final issue, and the Canadian poetry community lost what had been a vital part of its world. Dorothy Livesay's letter to Crawley beautifully expresses her reaction to Crawley's declining passion for the work of CV, as well as her complex sense of loss:

not attracting enough quality manuscripts and that, in McCullagh's words, “Canadian poetry was moving in a direction he was not in step with.” In February 1953, CV published its final issue, and the Canadian poetry community lost what had been a vital part of its world. Dorothy Livesay's letter to Crawley beautifully expresses her reaction to Crawley's declining passion for the work of CV, as well as her complex sense of loss:

“I am sad, but not to cry. Where there is no enthusiasm, poetry perishes … your frequently expressed sense of disappointment – because work isn't the same as it was—does incline one to question: why should it be? How could it?”

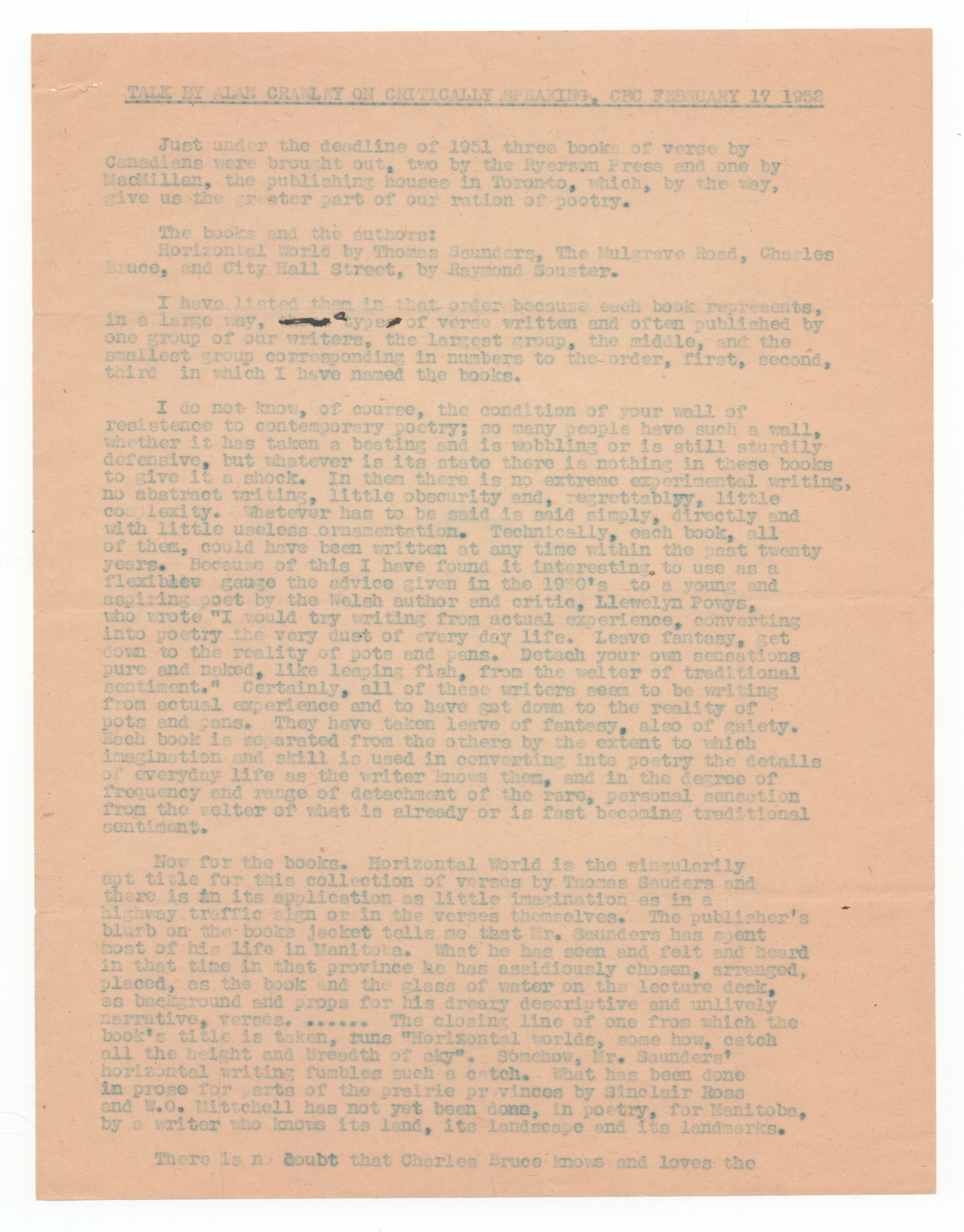

Evidence of CV's broad impact on the Canadian poetry scene is also abundant. The archival holdings contain Crawley's brief to the Massey  Commission, a Royal Commission that published a 1951 report which led to a wide range of federal funding for many cultural activities. There are also published and informal reviews of the magazine, several reviews of Crawley’s public readings, and the text of one of his CBC radio broadcasts from 17 February 1952.

Commission, a Royal Commission that published a 1951 report which led to a wide range of federal funding for many cultural activities. There are also published and informal reviews of the magazine, several reviews of Crawley’s public readings, and the text of one of his CBC radio broadcasts from 17 February 1952.

Unfortunately, no recording of Crawley reading poetry is known to have survived. Though his voice has been lost, his words and image remain in the Queen's Archives as a testament to his tremendous efforts and the accomplishments of Contemporary Verse.

McCullagh, Joan. Alan Crawley and Contemporary Verse. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1976.

McLaren, Floris Clark. “Contemporary Verse: A Canadian Quarterly.” Tamarack Review 3 (Spring 1957): 55-63.

Wilson, Ethel. “Of Alan Crawley.” Canadian Literature 19 (Winter 1964): 33-42.

Alan Crawley fonds, Queen’s University Archives

![Photograph of Dorothy Livesay, [ca. 1950]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01054.jpg?itok=LWKLNwSD)

![Letter from Bill [William Arthur] Deacon to [Hugh] Eayrs, 19 November 1923](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01057.jpg?itok=0IakPt-H)