Deemed “authentic”: Basil H. Johnston

Brendan Frederick R. Edwards

Basil H. Johnston (Anishinaabe) (1929–) was born on the Parry Island Indian Reserve in Ontario, and is a member of the Cape Croker First Nation (Neyaashiinigmiing), where he currently resides. Educated in reserve schools at Cape Croker and Spanish, Ontario, Johnston earned a B.A. with Honours from Loyola College in Montreal, and completed a secondary school teaching certificate at the Ontario College of Education. He taught high school in North York, Ontario from 1962 to 1969, before taking a position in the Ethnology Department of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto. He remained at the ROM until 1994, to initiate a Native approach to teaching at the museum, and to record and celebrate Ojibway (Anishinaabe) heritage, especially language and mythology. He has lectured at a number of universities, including the University of Saskatchewan and Trent University.

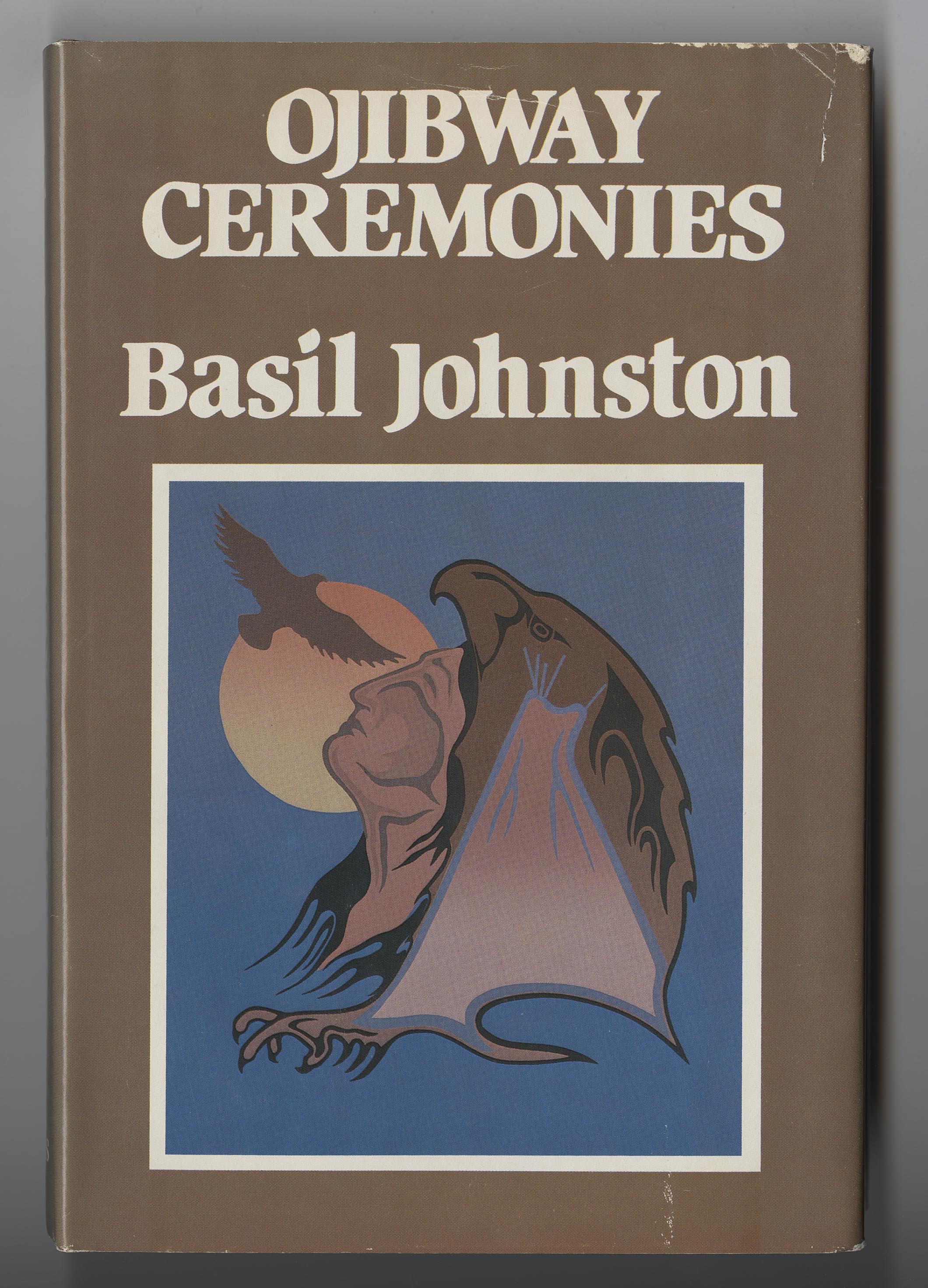

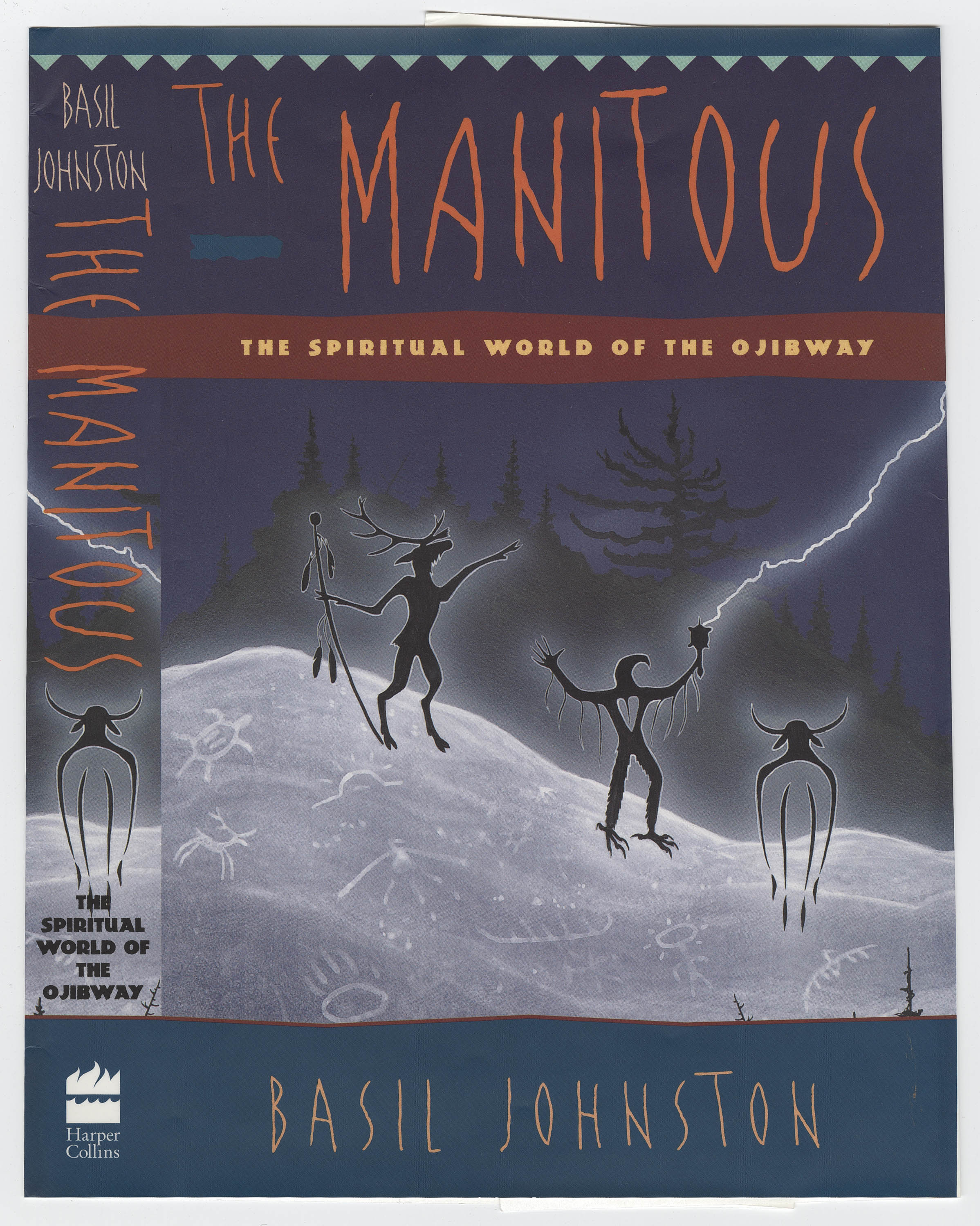

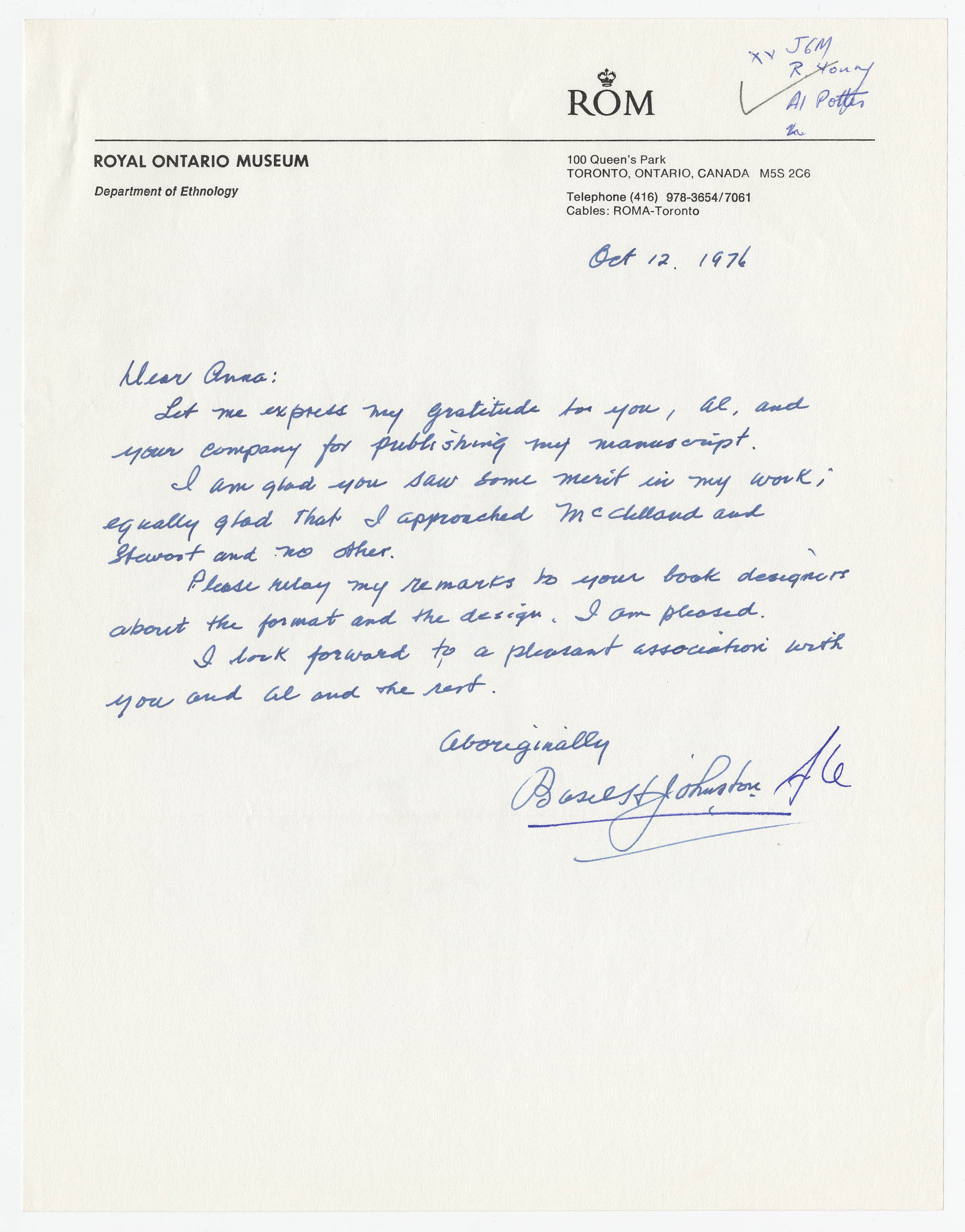

Johnston has been a highly respected writer, storyteller, language teacher, and scholar since his first writings were published in 1970. His numerous short stories, essays, articles, and poems have appeared in several Aboriginal publications, as well as The Educational Courier, Canadian Fiction Magazine, and the University of Lethbridge’s literary journal, Whetstone, among others. Johnston’s first serious publishing relationship was with McClelland & Stewart (M&S), where he forged a long-lasting relationship with Anna Porter in 1975. Johnston published Ojibway Heritage (1976), Moose Meat & Wild Rice (1978), and Ojibway Ceremonies (1982) with M&S before moving on to publish with Porter’s newly  minted Key Porter Books in the mid-1980s. Key Porter published the most successful of Johnston’s works, Indian School Days (1988), which humorously and heartbreakingly recounts his time as a student at Indian residential school. His book on the Ojibwa spirits, The Manitous (1995), was also issued by Key Porter.

minted Key Porter Books in the mid-1980s. Key Porter published the most successful of Johnston’s works, Indian School Days (1988), which humorously and heartbreakingly recounts his time as a student at Indian residential school. His book on the Ojibwa spirits, The Manitous (1995), was also issued by Key Porter.

Much of Johnston’s work focuses on the cultural and linguistic clash between Aboriginal peoples and government administrators, educators, and missionaries, but his writing also seeks to break existing narrow stereotypes of Indians and to demonstrate the complexities and diversity of Aboriginal life.

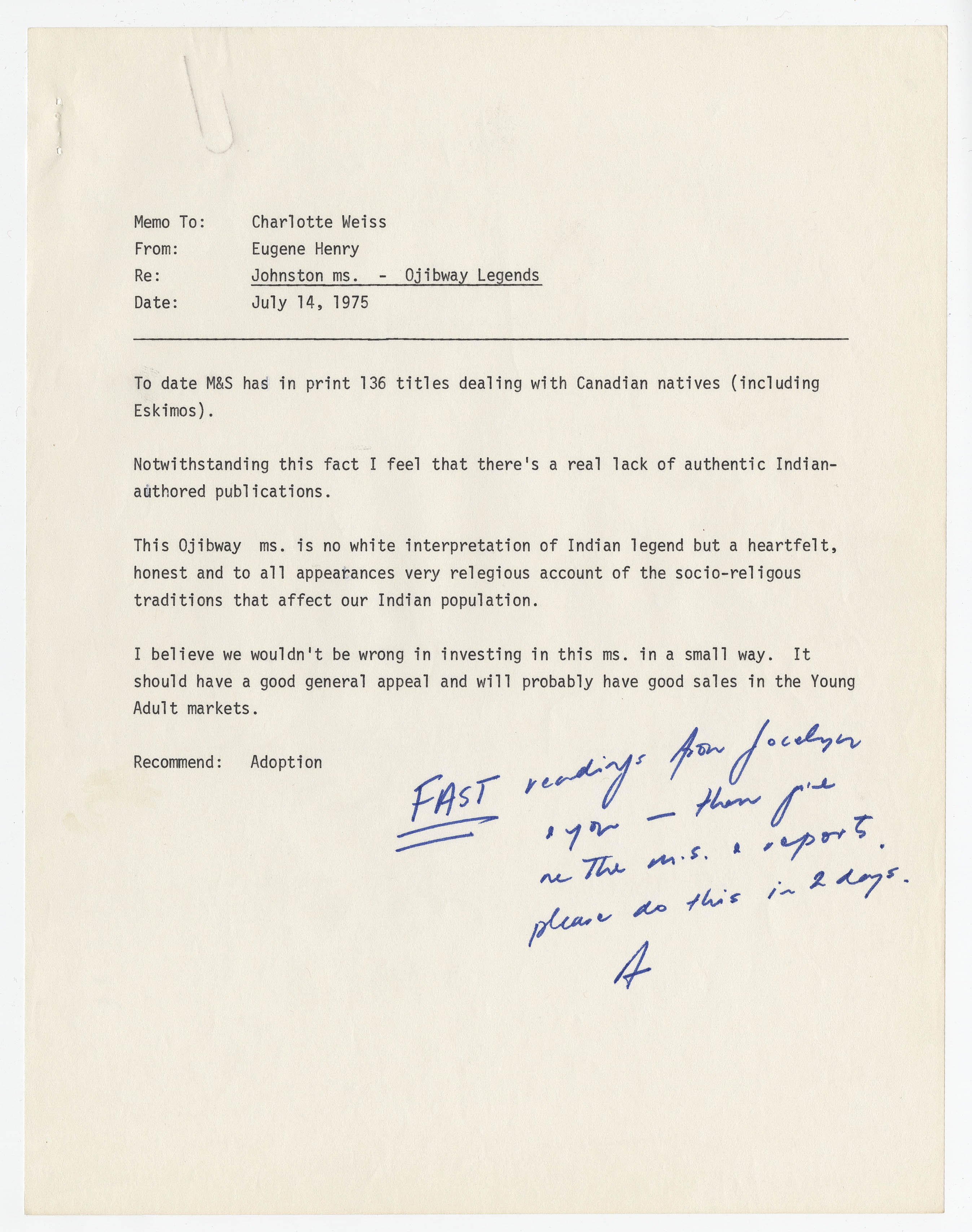

Both Ojibway Heritage and Moose Meat were initially met with resistance by some editors and readers at M&S, but the works prevailed thanks in no small part to the personal support of Jack McClelland and Anna Porter. A commitment on the part of the federal government’s Department of Indian Affairs to buy up to $5,000 worth of Ojibway Heritage (931 copies in total) helped to initially spur M&S to publish this title. The Department’s support meant that the book would be guaranteed a profit. Ojibway Heritage was seen by McClelland, Porter, and a handful of other editors at M&S as addressing “a real lack of authentic Indian-authored publications.” As Eugene Henry observed in 1975, M&S had “136 titles dealing with Canadian natives (including Eskimos)” but very few authored by Aboriginal people. With regards to Ojibway Heritage, Henry noted, “this Ojibway ms. is no white interpretation of

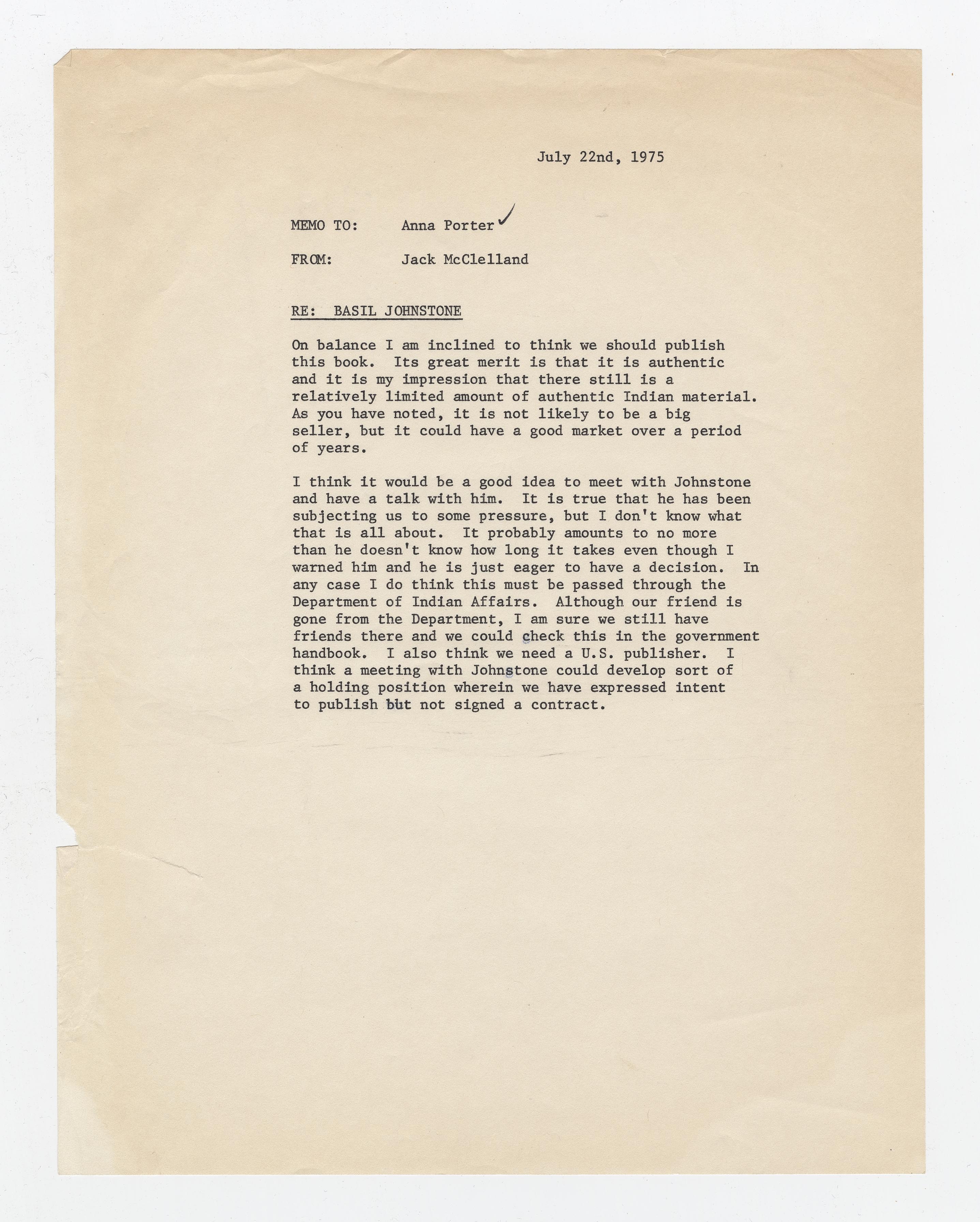

Both Ojibway Heritage and Moose Meat were initially met with resistance by some editors and readers at M&S, but the works prevailed thanks in no small part to the personal support of Jack McClelland and Anna Porter. A commitment on the part of the federal government’s Department of Indian Affairs to buy up to $5,000 worth of Ojibway Heritage (931 copies in total) helped to initially spur M&S to publish this title. The Department’s support meant that the book would be guaranteed a profit. Ojibway Heritage was seen by McClelland, Porter, and a handful of other editors at M&S as addressing “a real lack of authentic Indian-authored publications.” As Eugene Henry observed in 1975, M&S had “136 titles dealing with Canadian natives (including Eskimos)” but very few authored by Aboriginal people. With regards to Ojibway Heritage, Henry noted, “this Ojibway ms. is no white interpretation of  Indian legend but a heartfelt, honest and to all appearances very relegious [sic] account of the socio-religious traditions that affect our Indian population.” Similarly, McClelland stated: “on balance I am inclined to think we should publish this book. Its great merit is that it is authentic and it is my impression that there still is a relatively limited amount of authentic Indian material.” Indeed, Johnston’s “authenticity” appears to have been the impetus for M&S to publish Ojibway Heritage. But a degree of hesitation was certainly evident. As another editor commented, “I’m afraid I can’t be wholeheartedly enthusiastic about this m.s. My main doubt is the potential market. Probably there is a dearth of ‘genuine’ Indian material – I don’t know. I always somehow dislike the thought of people buying books like this and lauding a culture that their ancestors were quite happy to destroy, and who themselves would be most reluctant to restore the Indians what is ‘rightfully’ theirs.”

Indian legend but a heartfelt, honest and to all appearances very relegious [sic] account of the socio-religious traditions that affect our Indian population.” Similarly, McClelland stated: “on balance I am inclined to think we should publish this book. Its great merit is that it is authentic and it is my impression that there still is a relatively limited amount of authentic Indian material.” Indeed, Johnston’s “authenticity” appears to have been the impetus for M&S to publish Ojibway Heritage. But a degree of hesitation was certainly evident. As another editor commented, “I’m afraid I can’t be wholeheartedly enthusiastic about this m.s. My main doubt is the potential market. Probably there is a dearth of ‘genuine’ Indian material – I don’t know. I always somehow dislike the thought of people buying books like this and lauding a culture that their ancestors were quite happy to destroy, and who themselves would be most reluctant to restore the Indians what is ‘rightfully’ theirs.”

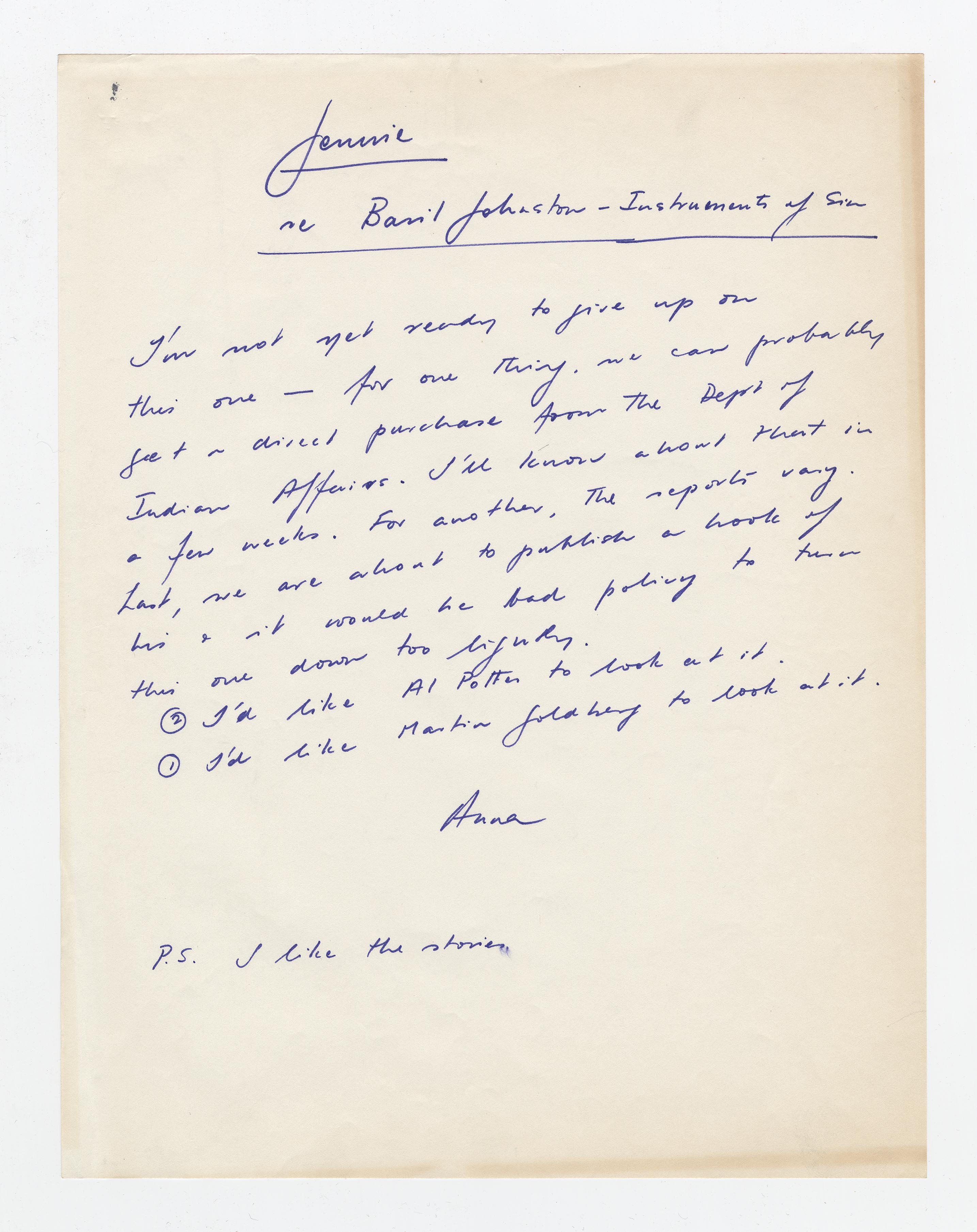

Reluctance on behalf of some editors was even more evident when it came to considering Moose Meat & Wild Rice. One editor who had fought for the publication of Ojibway Heritage, recommended the rejection of Moose Meat partly on the grounds that Indians were, in his opinion, “currently passé.” Another reader noted “an increasing resistance in the trade of Indian books of any kind.” And as Al Potter of M&S observed in his uncertain assessment of the manuscript, there was a “long list of chicken reports,” i.e., uncertain or outright negative reader reports, on the manuscript. Anna Porter, however, fought for the title to be published, convinced that once again the Department of Indian Affairs would commit to a direct purchase of the book; she also liked

Reluctance on behalf of some editors was even more evident when it came to considering Moose Meat & Wild Rice. One editor who had fought for the publication of Ojibway Heritage, recommended the rejection of Moose Meat partly on the grounds that Indians were, in his opinion, “currently passé.” Another reader noted “an increasing resistance in the trade of Indian books of any kind.” And as Al Potter of M&S observed in his uncertain assessment of the manuscript, there was a “long list of chicken reports,” i.e., uncertain or outright negative reader reports, on the manuscript. Anna Porter, however, fought for the title to be published, convinced that once again the Department of Indian Affairs would commit to a direct purchase of the book; she also liked  the stories and admitted, “we are about to publish a[nother] book of his [Ojibway Heritage] and it would be bad policy to turn this one down too lightly.” Indeed, Johnston had approached Porter directly with the Moose Meat collection shortly after he was offered the contract for Ojibway Heritage. In a letter to Porter in reference to “Instruments of Sin” (the original title for the collection that would become Moose Meat), Johnston observed that to his knowledge “no attempt has been made to date to record and recount Indian humour … all stories are based on actual incidents … [and] perhaps the stories are not exclusively Indian, hopefully they have a more universal appeal.”

the stories and admitted, “we are about to publish a[nother] book of his [Ojibway Heritage] and it would be bad policy to turn this one down too lightly.” Indeed, Johnston had approached Porter directly with the Moose Meat collection shortly after he was offered the contract for Ojibway Heritage. In a letter to Porter in reference to “Instruments of Sin” (the original title for the collection that would become Moose Meat), Johnston observed that to his knowledge “no attempt has been made to date to record and recount Indian humour … all stories are based on actual incidents … [and] perhaps the stories are not exclusively Indian, hopefully they have a more universal appeal.”

Once again, Johnston’s “authenticity” as a genuine Indian author may have been the ultimate deciding factor in publishing Moose Meat & Wild Rice. One editor reported of Johnston’s second submission to the publisher:

I feel this manuscript really has merit: its [sic] such a nice change from the old don’t-say-anything-less-than-flattering-about-indians-or-they’ll-know-you-think-their-inferior [sic] crap.

There are some things that Indians and bleeding heart’s [sic] won’t find flattering or even pleasant, but, christ [sic], there will never be modern (as opposed to assimilated) Indian writing until posing gives way to self-awareness. Good for Basil Johnston!

Thus began the long and distinguished career of one of Canada’s most successful and widely-read contemporary Aboriginal authors. For his efforts in giving voice to the Ojibway people, Johnston has received the Order of Ontario, honorary doctorates from the University of Toronto and Laurentian University, an Aboriginal Achievement Award for Heritage and Spirituality, and a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2007 Anskohk Aboriginal Literary Awards. McClelland & Stewart would also honour Johnston by including Moose Meat & Wild Rice as one of its “Essential 100” titles in promotional materials relating to their 100-year anniversary celebrations in 2006.

Thus began the long and distinguished career of one of Canada’s most successful and widely-read contemporary Aboriginal authors. For his efforts in giving voice to the Ojibway people, Johnston has received the Order of Ontario, honorary doctorates from the University of Toronto and Laurentian University, an Aboriginal Achievement Award for Heritage and Spirituality, and a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2007 Anskohk Aboriginal Literary Awards. McClelland & Stewart would also honour Johnston by including Moose Meat & Wild Rice as one of its “Essential 100” titles in promotional materials relating to their 100-year anniversary celebrations in 2006.

Bruce, Kimberly. "Profile of Basil H. Johnston." In Hidden in Plain Sight: contributions of Aboriginal peoples to Canadian identity and culture, ed. David R. Newhouse, Cora J. Voyageur, and Dan Beavon, 200-202. University of Toronto Press, 2005.

Scott, Jamie S. "Colonial, Neo-Colonial, Post-Colonial: Images Of Christian

Missions In Hiram A. Cody's 'The Frontiersman,' Rudy Wiebe's 'First And Vital Candle' And Basil Johnston's 'Indian School Days'." Journal of Canadian Studies 32.3 (1997): 140-61.

Smythe Groening, Laura. "The Healing Aesthetic of Basil H. Johnston." Listening to Old Woman Speak: Natives and alterNatives in Canadian Literature. McGill-Queen's Press, 2004. 144-151.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd. fonds, McMaster University

Key Porter Books fonds, McMaster University