Ethel Brant Monture: “A One-Woman Crusade”

Brendan Frederick R. Edwards

Considered an authority on the history and culture of the Six Nations, Ethel Brant Monture (1894-1977) reached a relatively wide audience through her  writings. Although Monture’s circle of influence was broad, her Native lineage is also notable. The fifth of nine children born to Robert and Lydia Brant, who lived on the New Credit Reserve (known today as the Missassaugas of New Credit First Nation, located close to Six Nations Reserve, near Hagersville, Ontario), Monture was a great-great grandchild of Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, through his third wife Catherine Croghan. “Interested intensely in books” at a young age, Monture’s biographers claim she “could read and peel potatoes at the same time.” Encouraged by her father to continue reading, Monture acquired “the basis” of her knowledge in Iroquois and Aboriginal history and culture while attending elementary school on the Reserve. Although she went to high school in nearby Hagersville, she did not obtain a diploma or attend university. After marrying and raising two children, Monture began writing

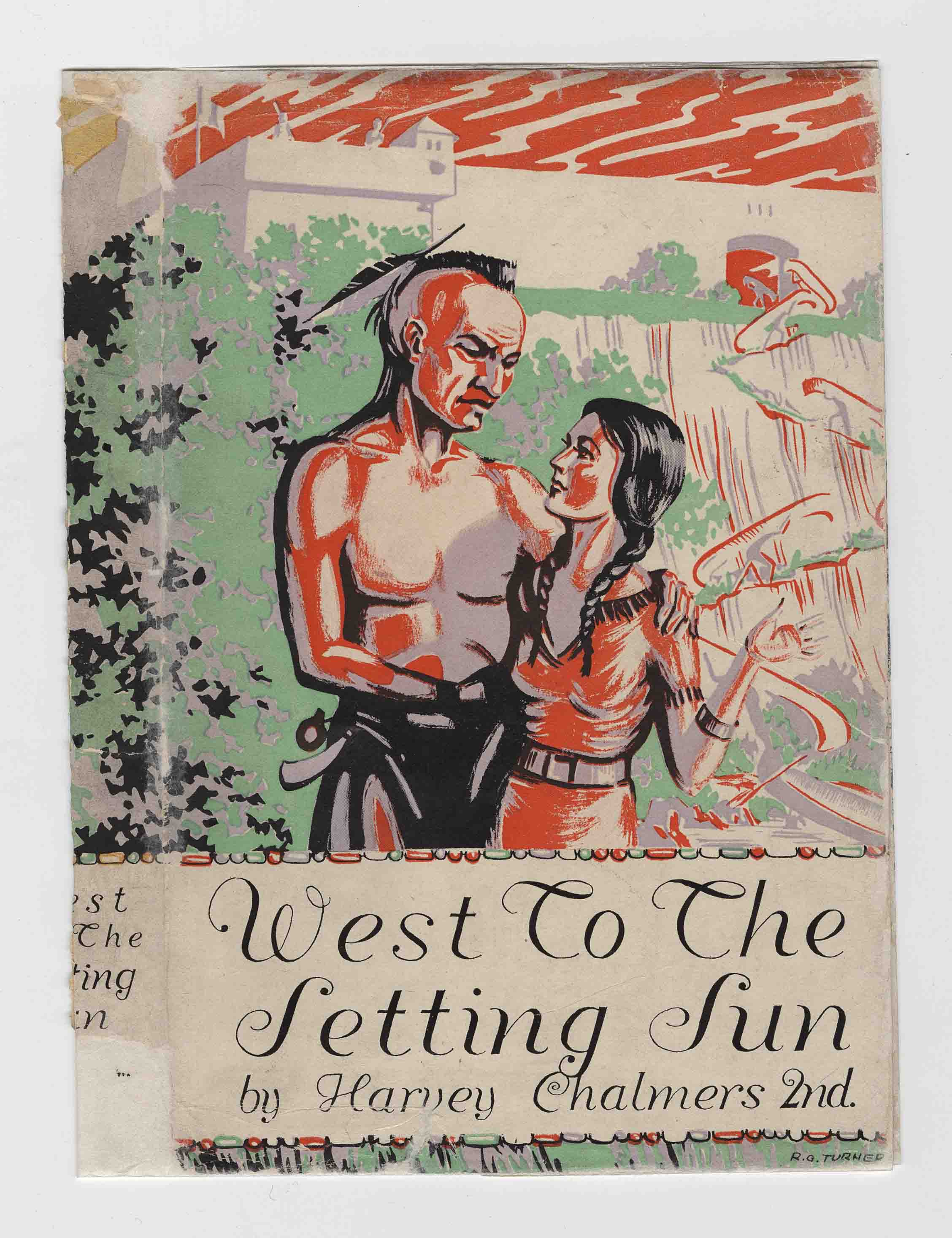

writings. Although Monture’s circle of influence was broad, her Native lineage is also notable. The fifth of nine children born to Robert and Lydia Brant, who lived on the New Credit Reserve (known today as the Missassaugas of New Credit First Nation, located close to Six Nations Reserve, near Hagersville, Ontario), Monture was a great-great grandchild of Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, through his third wife Catherine Croghan. “Interested intensely in books” at a young age, Monture’s biographers claim she “could read and peel potatoes at the same time.” Encouraged by her father to continue reading, Monture acquired “the basis” of her knowledge in Iroquois and Aboriginal history and culture while attending elementary school on the Reserve. Although she went to high school in nearby Hagersville, she did not obtain a diploma or attend university. After marrying and raising two children, Monture began writing  and lecturing in her late thirties. Driven by a “desire to see a history of the Indian people that had been written by an Indian person,” she undertook research into the life of her great-great grandfather. A great deal of Monture’s creative writing was done in collaboration with Harvey Chalmers, an American author, novelist, and short story writer who specialized in books relating to early New York State and American history. Monture assisted Chalmers on West to the Setting Sun (1943) —a historical novel about Iroquois life in the era of Joseph Brant (Thayendanega), considered by the American Seneca writer, historian, and anthropologist, Arthur C. Parker, as a positive example of fiction following in the literary tradition of James Fenimore Cooper) — and Joseph Brant: Mohawk (1955). She wrote and published her own work, Famous Indians, in 1960.

and lecturing in her late thirties. Driven by a “desire to see a history of the Indian people that had been written by an Indian person,” she undertook research into the life of her great-great grandfather. A great deal of Monture’s creative writing was done in collaboration with Harvey Chalmers, an American author, novelist, and short story writer who specialized in books relating to early New York State and American history. Monture assisted Chalmers on West to the Setting Sun (1943) —a historical novel about Iroquois life in the era of Joseph Brant (Thayendanega), considered by the American Seneca writer, historian, and anthropologist, Arthur C. Parker, as a positive example of fiction following in the literary tradition of James Fenimore Cooper) — and Joseph Brant: Mohawk (1955). She wrote and published her own work, Famous Indians, in 1960.

Monture’s writing was straightforward, speaking directly to the historical achievements and modern possibilities of Aboriginal peoples. Her calls for improved Indian education were direct, and reached a wide readership through publications such as Maclean’s magazine.

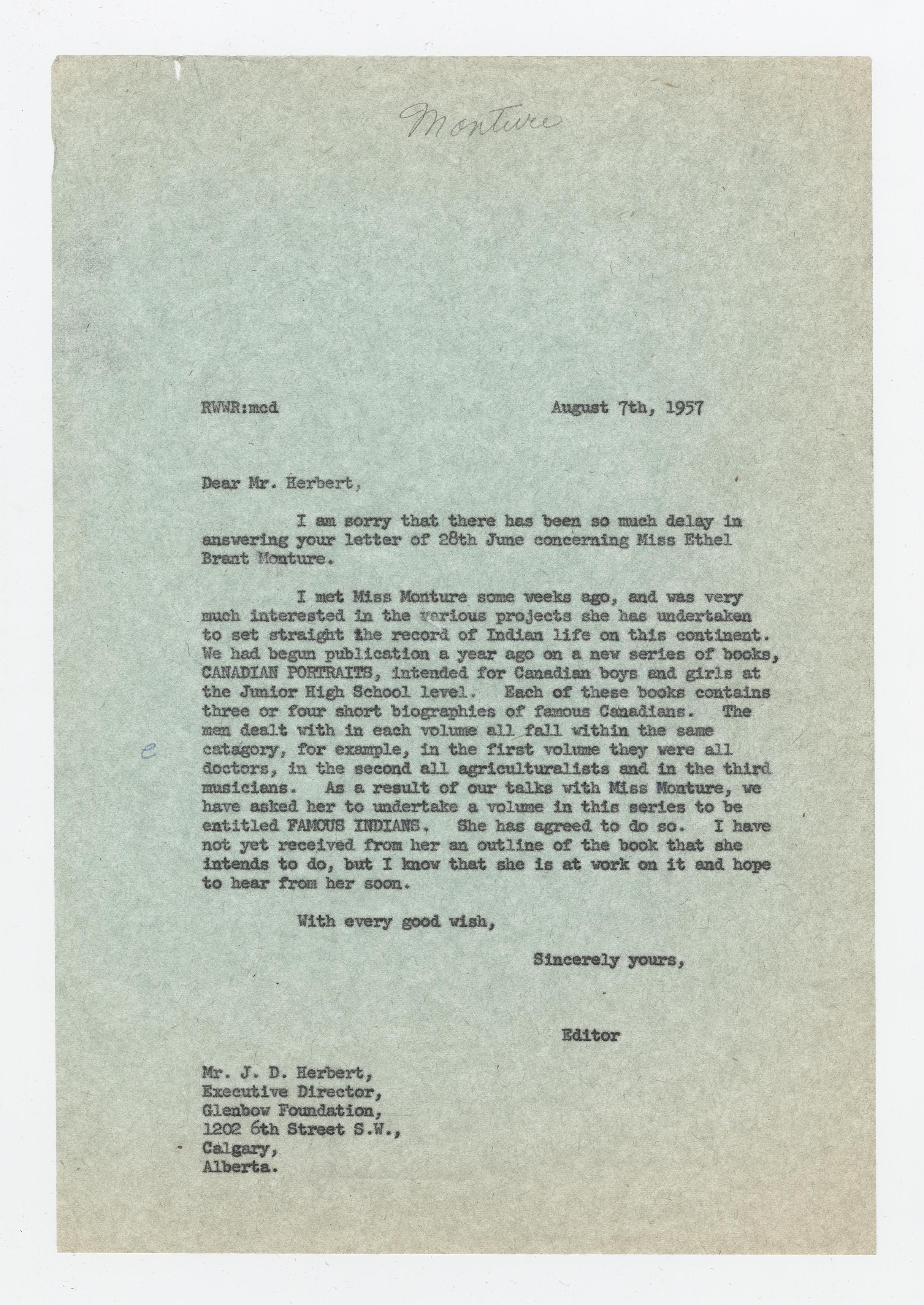

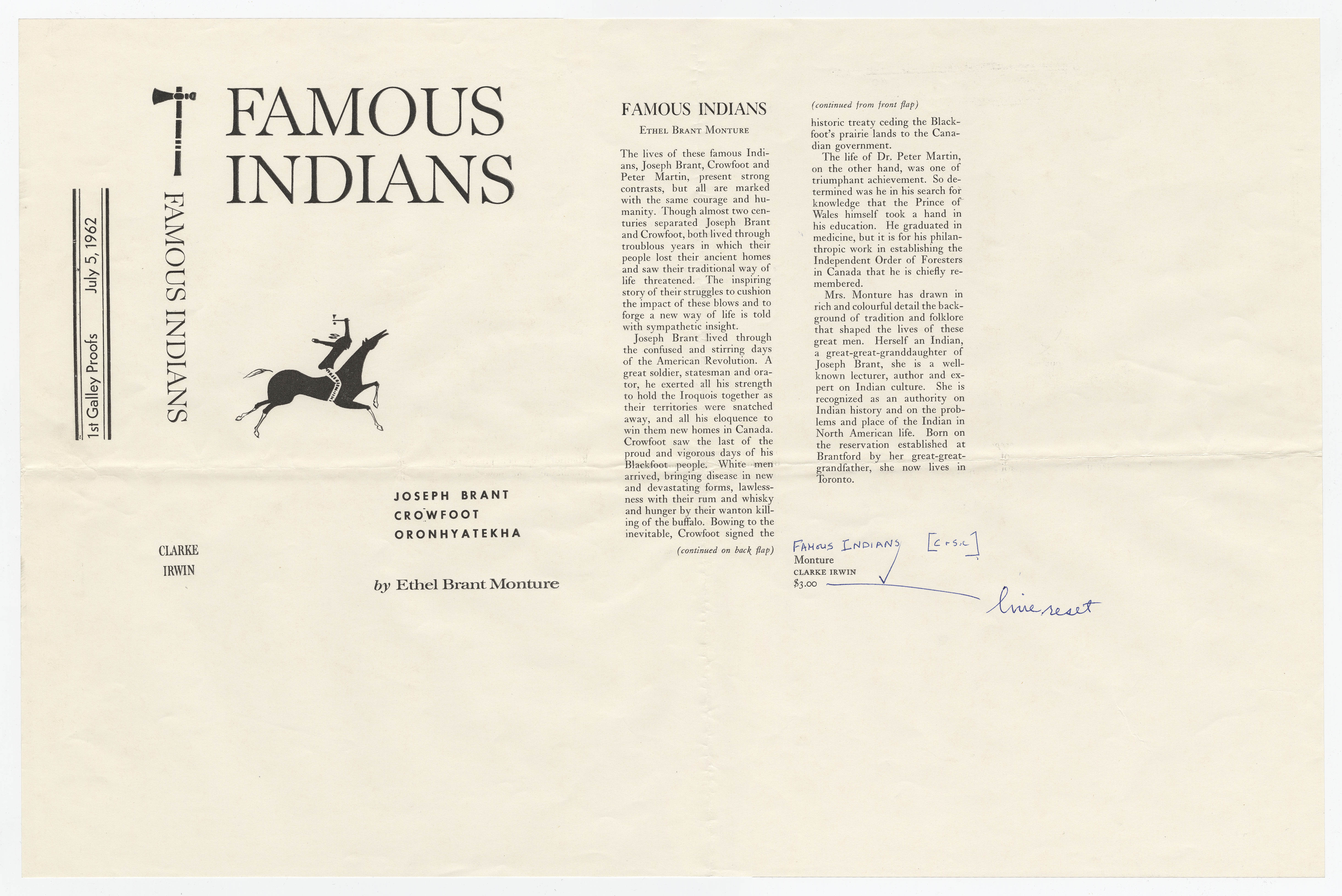

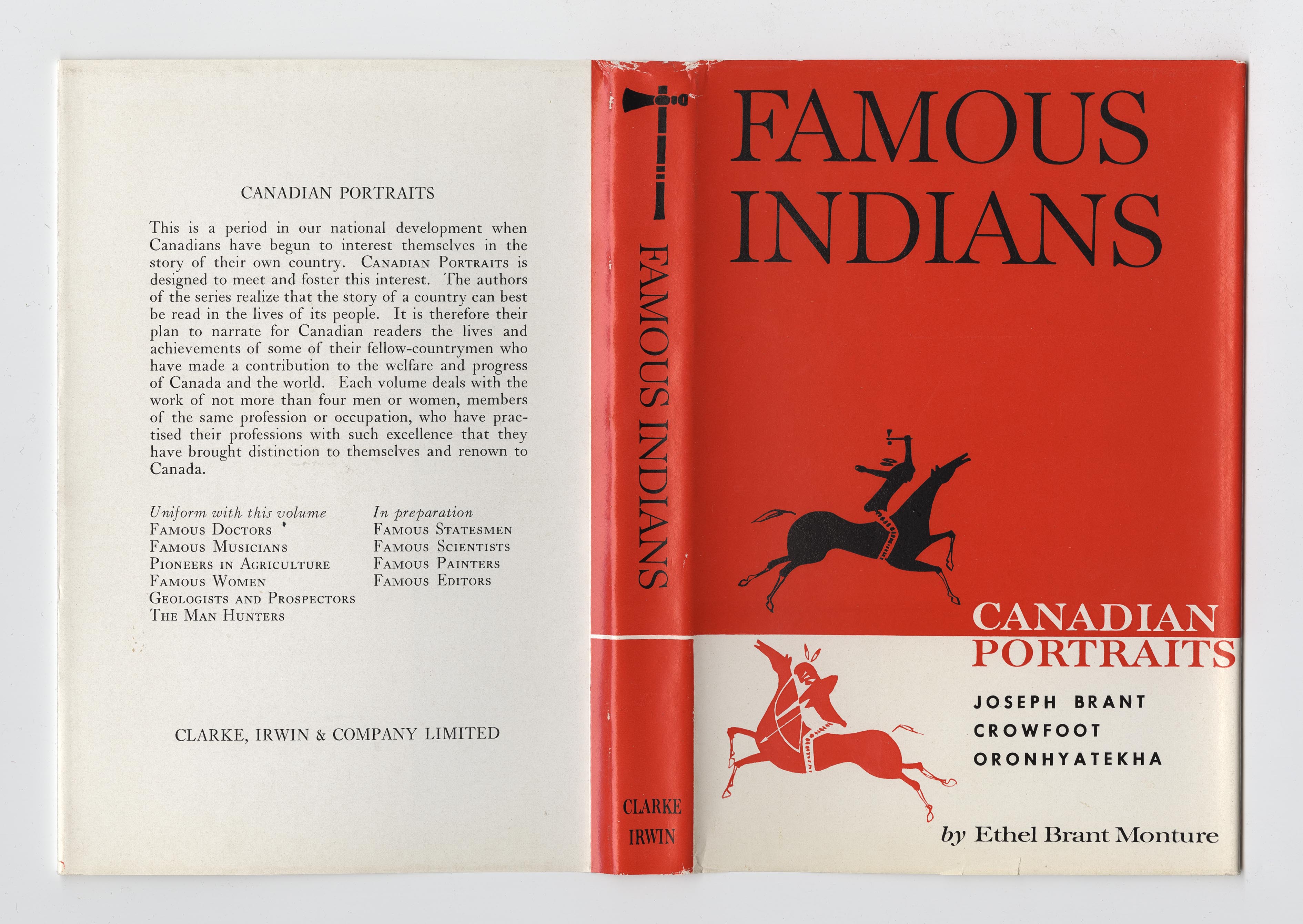

Monture’s Famous Indians was published by Clarke, Irwin in 1960 as part of the Canadian Portraits series, and funded in part by the Glenbow Foundation through funds available “for serious projects relating to Indian history or problems, etc.” Monture was approached by editors at Clarke, Irwin to contribute to their “Canadian Portraits” series on the basis of her reputation as a public lecturer on Aboriginal issues. First conceived in the mid-1950s as a series directed at students at the junior high school level, each book featuring three or four short biographies of famous Canadians, the “Canadian Portraits” series had, prior to Famous Indians, included works on noted Canadian musicians, doctors, women, pioneers in agriculture, anthropologists, and geologists and prospectors. The series continued into the 1960s and 70s, with further titles on famous Canadian wilderness writers, bush pilots, fighter pilots, and composers.

Envisioned by Monture as the first of several similar projects to “set straight the record of Indian life on this continent,” and first accepted for publication in early 1957, Famous Indians is a collection of biographies of Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), Peter Martin (Oronhyatekha), and Crowfoot (the Blackfoot chief). Delayed in publication due to the necessity of rewriting, at least one editor considered the manuscript “very promising – anything but boring,” but also “garbled… the sequence of ideas chaotic… [and] simply not organized.” Although not credited, an unidentified “co-authoress” was employed to help with revisions.

Envisioned by Monture as the first of several similar projects to “set straight the record of Indian life on this continent,” and first accepted for publication in early 1957, Famous Indians is a collection of biographies of Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), Peter Martin (Oronhyatekha), and Crowfoot (the Blackfoot chief). Delayed in publication due to the necessity of rewriting, at least one editor considered the manuscript “very promising – anything but boring,” but also “garbled… the sequence of ideas chaotic… [and] simply not organized.” Although not credited, an unidentified “co-authoress” was employed to help with revisions.

Describing herself as “one of the great living authorities on Indian Culture and History” and “an author of several books,” Monture may have let her immense  self-confidence get in the way of authentic self-description. Nonetheless, her self-portrayal has stuck. She certainly was knowledgeable and passionate; and although she only wrote one book herself, and assisted in the publication of two others, her speeches and lecture notes would have filled several volumes. Monture anticipated that she would publish further titles, but ill health unfortunately prevented her from doing so; in 1973, she suffered a stroke from which she never fully recovered, and the autobiographical childhood narrative she was purportedly working on at that time was never completed.

self-confidence get in the way of authentic self-description. Nonetheless, her self-portrayal has stuck. She certainly was knowledgeable and passionate; and although she only wrote one book herself, and assisted in the publication of two others, her speeches and lecture notes would have filled several volumes. Monture anticipated that she would publish further titles, but ill health unfortunately prevented her from doing so; in 1973, she suffered a stroke from which she never fully recovered, and the autobiographical childhood narrative she was purportedly working on at that time was never completed.

Monture’s one-woman crusade to correct and reflect the historical reality of First Nations was one that would find considerable support from other Aboriginal (and non-Aboriginal) voices in the years following her death. Active at a time when Aboriginal authors in Canada were mostly ignored, Monture was important as one of Canada’s first female Aboriginal writers to be published in the mainstream popular press.

Monture’s one-woman crusade to correct and reflect the historical reality of First Nations was one that would find considerable support from other Aboriginal (and non-Aboriginal) voices in the years following her death. Active at a time when Aboriginal authors in Canada were mostly ignored, Monture was important as one of Canada’s first female Aboriginal writers to be published in the mainstream popular press.

Edwards, Brendan Frederick R. “A War of Wor(l)ds: Aboriginal writing in Canada during the ‘dark days’ of the early twentieth century.” Ph.D. thesis, Department of History, University of Saskatchewan, 2008.

“Ethel Brant Monture: Lecturer, Author, Expert on Indian Culture.” In Significant Lives: Profiles of Brant County Women. Brantford, Ont.: University Women’s Club of Brantford, 1997: 101-103.

Morgan, Cecilia. “Private Lives and Public Performances: Aboriginal Women in a Settler Society, Ontario, Canada, 1920s-1960s.” Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 4.3 (2003).

—. “Performing for ‘Imperial Eyes’: Bernice Loft and Ethel Brant Monture, Ontario, 1930s-60s,” in Contact Zones: Aboriginal and Settler Women in Canada’s Colonial Past. ed. Katie Pickles and Myra Rutherdale, 67-89. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2005.

Parker, Arthur C. “Sources and Range of Cooper’s Indian Lore.” James Fenimore Cooper: A Re-Appraisal. Cooperstown: New York State Historical Association, 1954: 85-6.

Porter, Cathy and Daniel Moses. Ethel Brant Monture. Brantford: Woodland Indian Cultural Education Centre, 1978: 1.

Clarke, Irwin & Company Limited fonds, McMaster University

![Fifth business; a novel by Robertson Davies, [1970]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00994.jpg?itok=g4eDrNpU)

![Fifth business; a novel by Robertson Davies, [1970]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00994-003.jpg?itok=uTPBTWYp)

![Fifth business; a novel by Robertson Davies, [1970]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00994-002.jpg?itok=lGR5KqNM)

![Canadian Wild Flowers [subscription book], 1867](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00997.jpg?itok=dF2KSi6N)

![Canadian Wild Flowers [subscription book], 1867](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00997-002.jpg?itok=FUqKOusX)

![Canadian Wild Flowers [subscription book], 1867](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00997-003.jpg?itok=Y2aSA22N)

![Canadian Wild Flowers [subscription book], 1870](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00999.jpg?itok=6A1L06uz)