Grey Owl and His Publishers

Donald B. Smith, University of Calgary

The Macmillan Canada fonds at McMaster University contains the largest collection of manuscript material relating to the writing career of Archibald  Stansfeld Belaney (1888-1938), who wrote under the name of Grey Owl in the 1930s. His writing career began in 1929 when he was forty-one years old. Anahareo, his Iroquois companion, encouraged him to write his first published article, which was purchased by the English periodical, Country Life. He then wrote a number of articles for the Canadian publication, Forest and Outdoors, published by the Canadian Forestry Association. When Country Life expressed interest in publishing a book by Belaney, he tried out his new name, Grey Owl, and the volume appeared as Men of the Last Frontier in 1931. Country

Stansfeld Belaney (1888-1938), who wrote under the name of Grey Owl in the 1930s. His writing career began in 1929 when he was forty-one years old. Anahareo, his Iroquois companion, encouraged him to write his first published article, which was purchased by the English periodical, Country Life. He then wrote a number of articles for the Canadian publication, Forest and Outdoors, published by the Canadian Forestry Association. When Country Life expressed interest in publishing a book by Belaney, he tried out his new name, Grey Owl, and the volume appeared as Men of the Last Frontier in 1931. Country  Life explained their North American Indian author’s background in a note in the book: “His father was a Scot, his mother an Apache Indian of New Mexico, and he was born somewhere near the Rio Grande forty odd years ago. ” Macmillan became his publisher in Canada when it issued a Canadian edition of The Men of the Last Frontier, also in 1931.

Life explained their North American Indian author’s background in a note in the book: “His father was a Scot, his mother an Apache Indian of New Mexico, and he was born somewhere near the Rio Grande forty odd years ago. ” Macmillan became his publisher in Canada when it issued a Canadian edition of The Men of the Last Frontier, also in 1931.

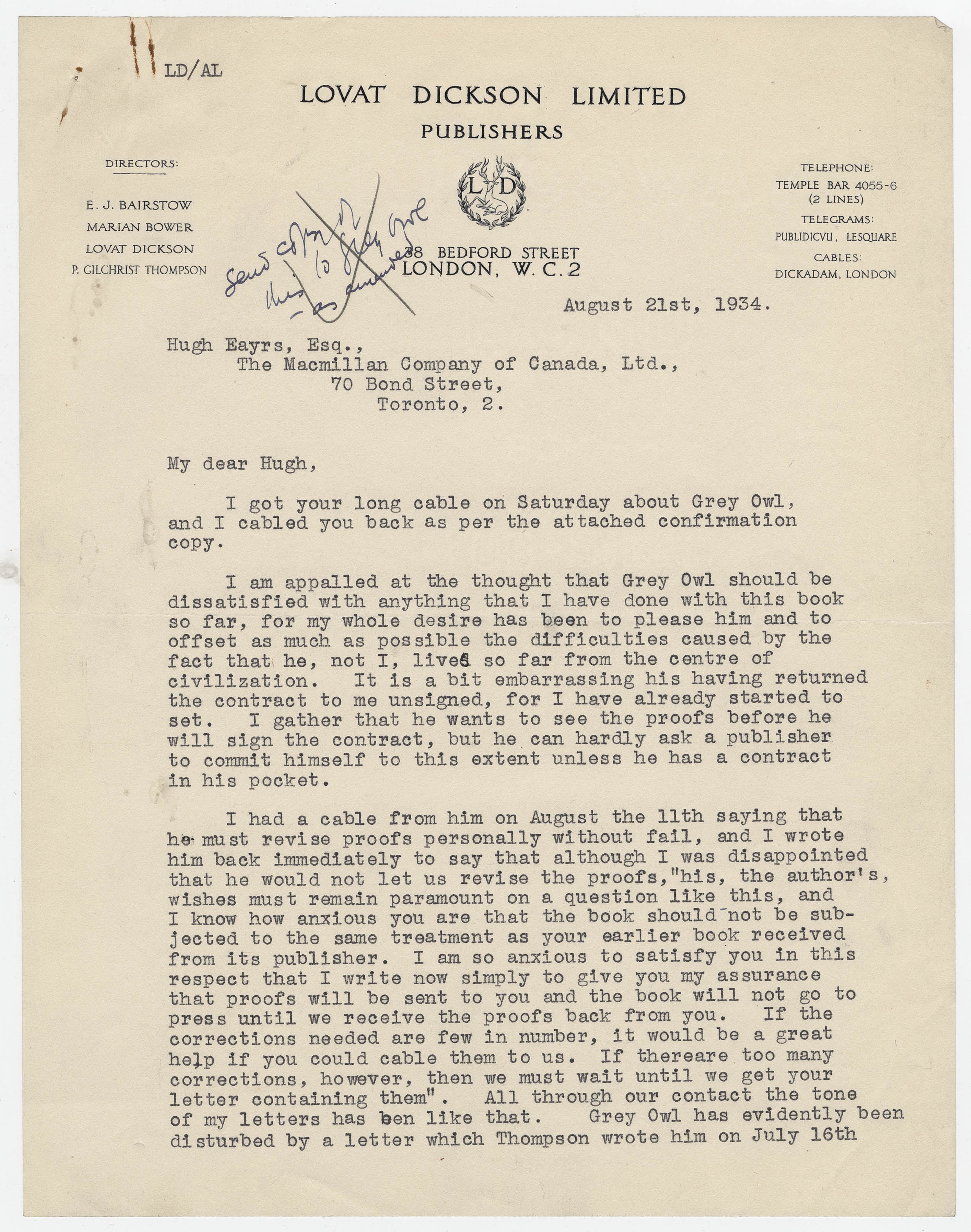

Grey Owl’s articles on the North, wildlife, and Aboriginal peoples, led to his appointment as a conservation officer, or caretaker of park animals, with the National Parks Branch of the Canadian government, first at Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba, and later at Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan where he completed his next three books. Hugh Eayrs, head of the Macmillans in Toronto, established a good working relationship with him. It was Eayrs who recommended that Lovat Dickson, a Canadian in London who had recently founded his own publishing company, Lovat Dickson Limited, become Grey Owl’s publisher in England.

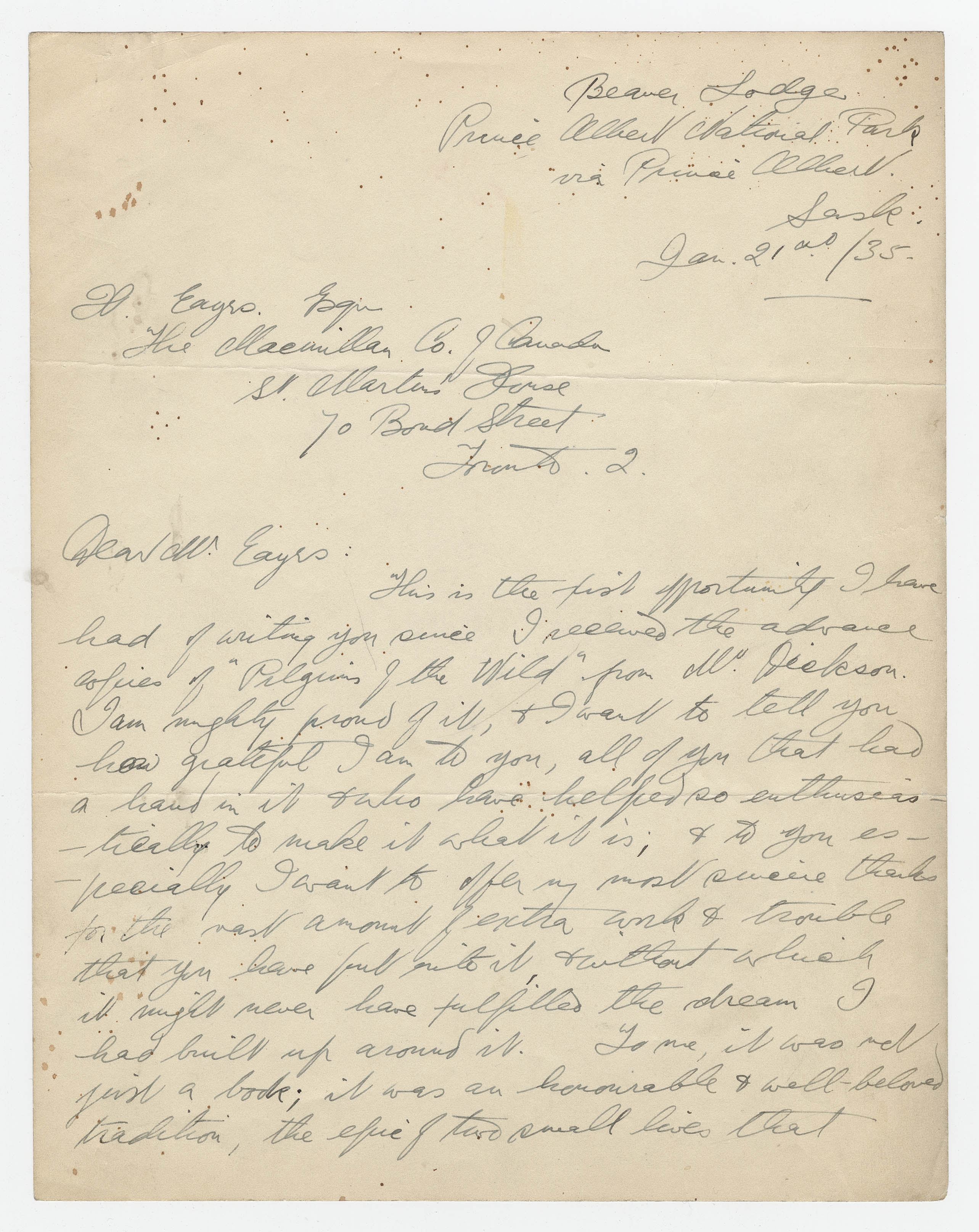

In Britain, Grey Owl’s popularity was phenomenal in the mid-1930s after the publication by Dickson of his second book, Pilgrims of the Wild, in 1934. It told the story of how, thanks to Anahareo’s influence, he became a conservationist. The following year, he published a children’s book entitled The Adventures of Sajo and Her Beaver People (1935). His books, his lectures, and films about him, made Grey Owl into an international celebrity. His last book, Tales of an Empty Cabin, appeared in 1936. Fortunately, the Macmillan Company’s extensive records, which contain ample correspondence with Lovat Dickson, allow for the full publishing history of Grey Owl’s books to be told.

In Britain, Grey Owl’s popularity was phenomenal in the mid-1930s after the publication by Dickson of his second book, Pilgrims of the Wild, in 1934. It told the story of how, thanks to Anahareo’s influence, he became a conservationist. The following year, he published a children’s book entitled The Adventures of Sajo and Her Beaver People (1935). His books, his lectures, and films about him, made Grey Owl into an international celebrity. His last book, Tales of an Empty Cabin, appeared in 1936. Fortunately, the Macmillan Company’s extensive records, which contain ample correspondence with Lovat Dickson, allow for the full publishing history of Grey Owl’s books to be told.

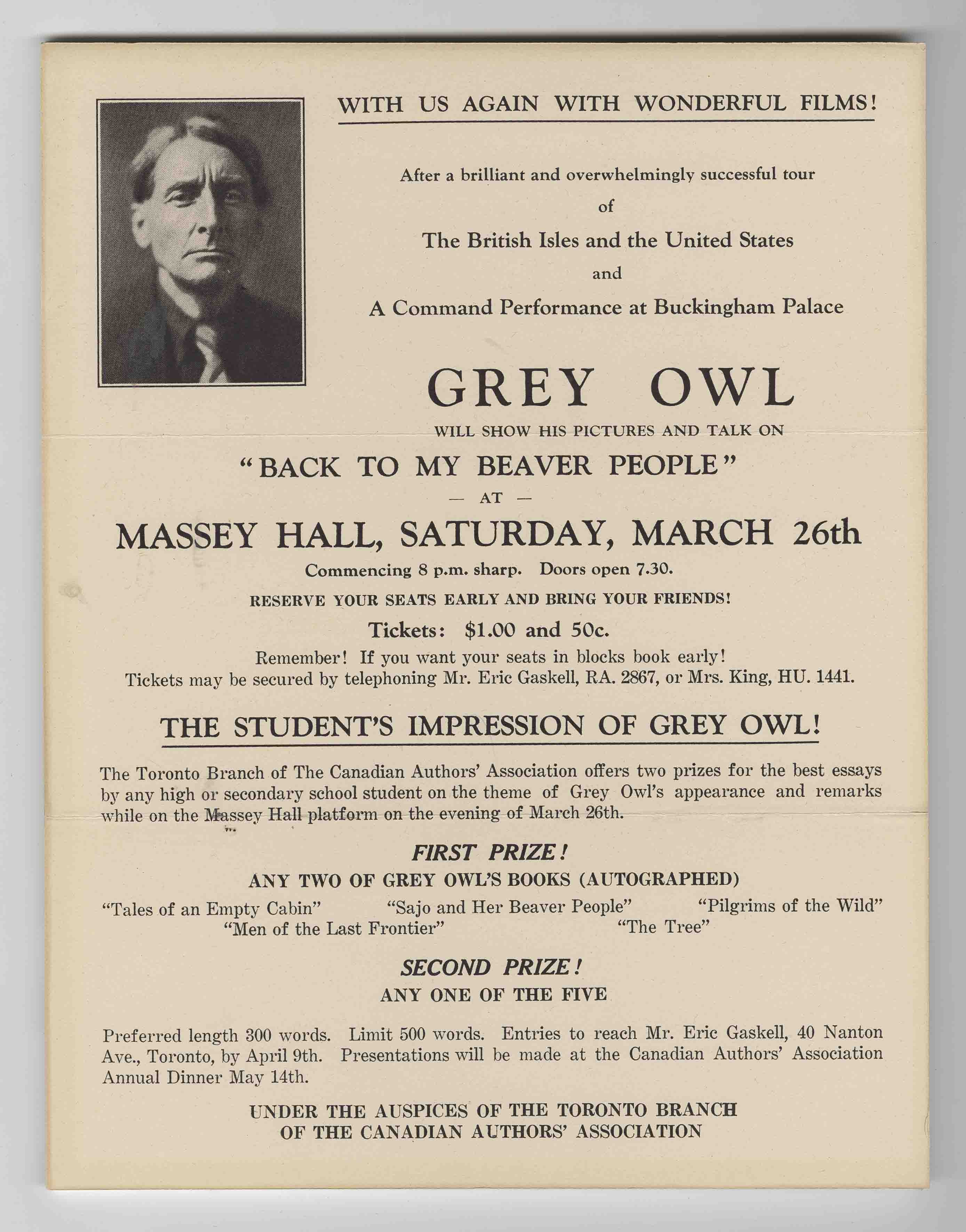

At Lovat Dickson’s invitation Grey Owl made a lecture tour of Britain in late 1935 and early 1936. The four-month tour proved extremely successful. The over-riding theme was; “Remember, you belong to Nature, not it to you.” The lectures, accompanied by Grey Owl’s films, focused on the vast northern forests and their human and animal inhabitants. A second and final three-month tour of Britain followed in late 1937, and included a Royal Command performance at Buckingham Palace before King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, and the two young princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. He followed this tour with a three-month series of performances in North America in early 1938.

At Lovat Dickson’s invitation Grey Owl made a lecture tour of Britain in late 1935 and early 1936. The four-month tour proved extremely successful. The over-riding theme was; “Remember, you belong to Nature, not it to you.” The lectures, accompanied by Grey Owl’s films, focused on the vast northern forests and their human and animal inhabitants. A second and final three-month tour of Britain followed in late 1937, and included a Royal Command performance at Buckingham Palace before King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, and the two young princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. He followed this tour with a three-month series of performances in North America in early 1938.

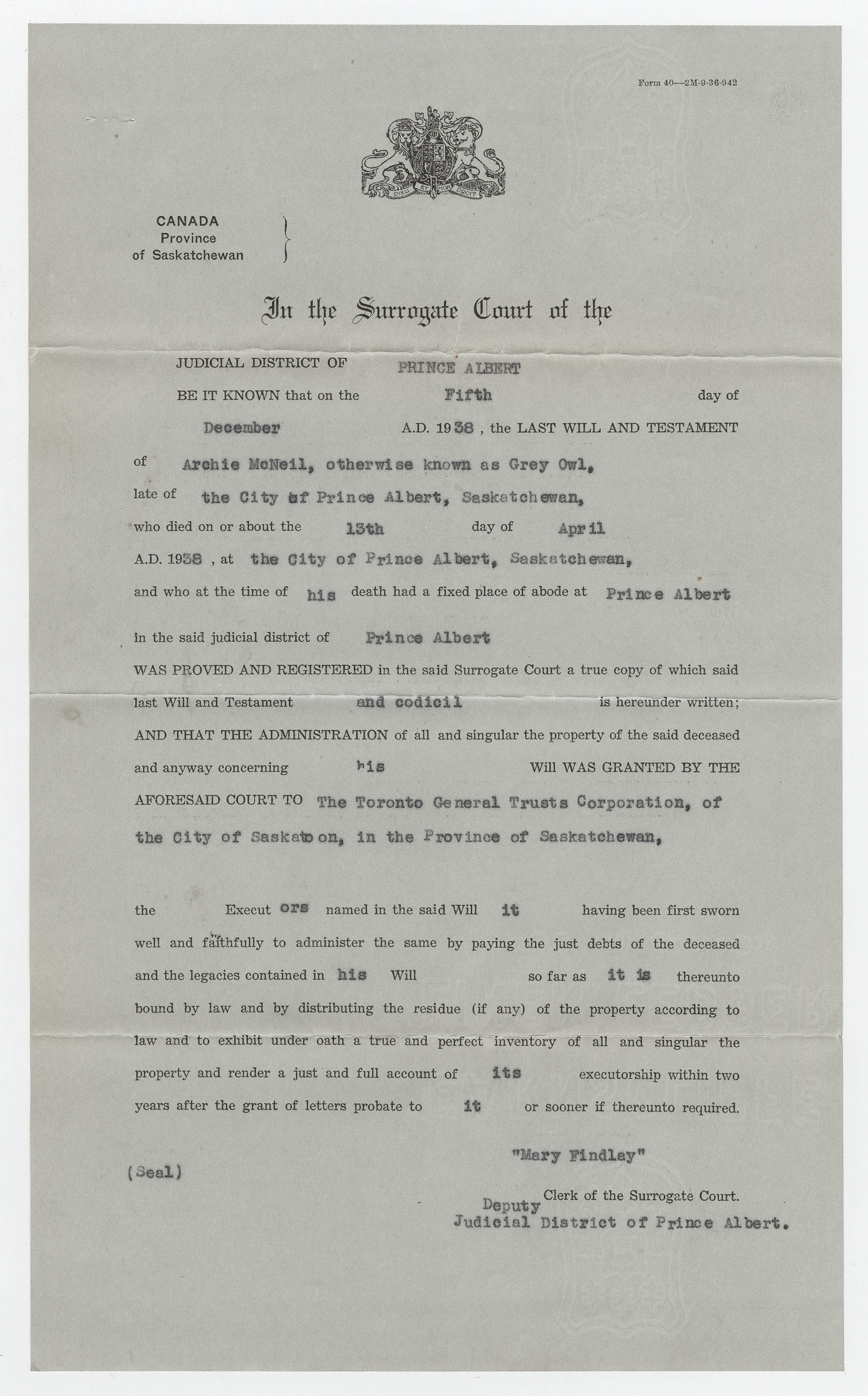

Grey Owl gave all his remaining physical and emotional strength to his campaign for conservation. In early April 1938 the pioneer environmentalist came back to Saskatchewan, totally exhausted. Only three days after his return to Beaver Lodge he was rushed to hospital in Prince Albert, where he died on 13 April, at the age of  forty-nine. The next day an editorial in the Toronto Globe and Mail termed Grey Owl the “most famous of Canadian Indians.” The media on two continents, as well as Grey Owl’s companion, Anahareo, and his publishers, Hugh Eayrs, and Lovat Dickson, had all accepted the author’s story of his family origins. A week after his death, Angele Egwuna, an Ojibwe woman from Temagami in northeastern Ontario, stepped forward, claiming that she was his legal wife, whom he had married at age twenty-one shortly after his arrival in Canada from England.

forty-nine. The next day an editorial in the Toronto Globe and Mail termed Grey Owl the “most famous of Canadian Indians.” The media on two continents, as well as Grey Owl’s companion, Anahareo, and his publishers, Hugh Eayrs, and Lovat Dickson, had all accepted the author’s story of his family origins. A week after his death, Angele Egwuna, an Ojibwe woman from Temagami in northeastern Ontario, stepped forward, claiming that she was his legal wife, whom he had married at age twenty-one shortly after his arrival in Canada from England.

The true story of Archie Belaney, born in 1888 and raised in Hastings, England, broke. This revelation, now well known, has become one of Canada’s greatest tales of self-invention. All his books remain in print in Canada. There  are also many translations. Despite his racial masquerade he is remembered today as one of Canada’s pioneer conservationists.

are also many translations. Despite his racial masquerade he is remembered today as one of Canada’s pioneer conservationists.

Grey Owl’s correspondence in the Macmillan Canada archives survives, and constitutes a rich lode of information about the professional relationship of Grey Owl with his Canadian publisher.

Anahareo. Devil in Deerskins: My Life With Grey Owl. Toronto: New Press, 1972.

Braz, Albert. "The Modern Hiawatha: Grey Owl's Construction of His Aboriginal Self." in Autobiography in Canada Critical Directions. 53-68. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2005.

Dickson, Lovat. Wilderness Man: The Strange Story of Grey Owl. Toronto: Macmillan, 1973.

Ruffo, Armand Garnet. Grey Owl : the mystery of Archie Belaney. Regina: Coteau, 1996.

Smith, Donald B. From the Land of Shadows: The Making of Grey Owl. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1990; repr. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 1999.

"St. Archie of the Wild. Grey Owl's Account of His 'Natural' Conversion," in Other Selves: Animals in the Canadian Literary Imagination, ed. Janice Fiamengo, 206-226. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2007.

Grey Owl collection, McMaster University

Macmillan Company of Canada fonds, McMaster University