Locks’ Press, the private press of Fred and Margaret Lock, Kingston, Ontario: A Personal Narrative

Margaret Lock

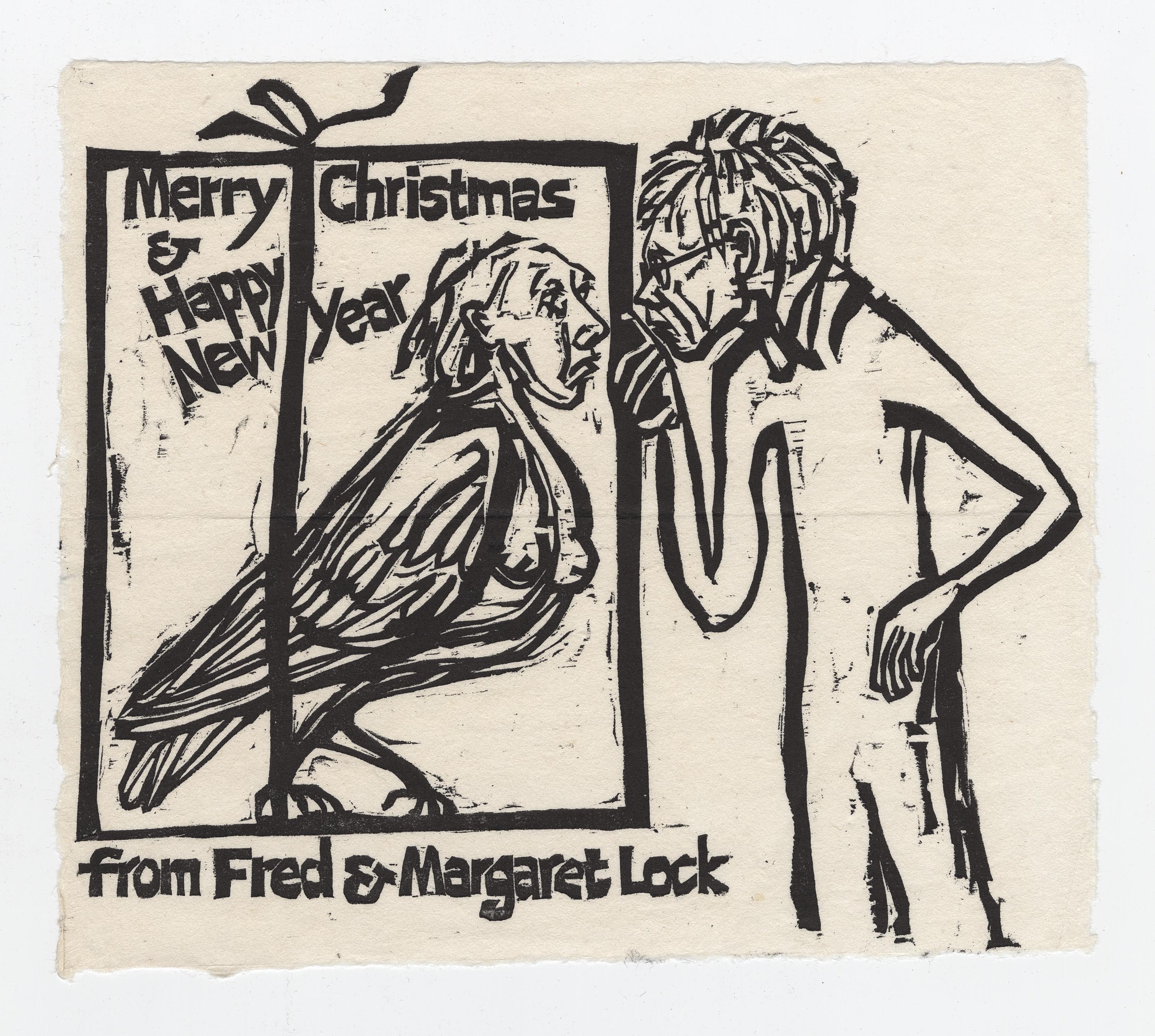

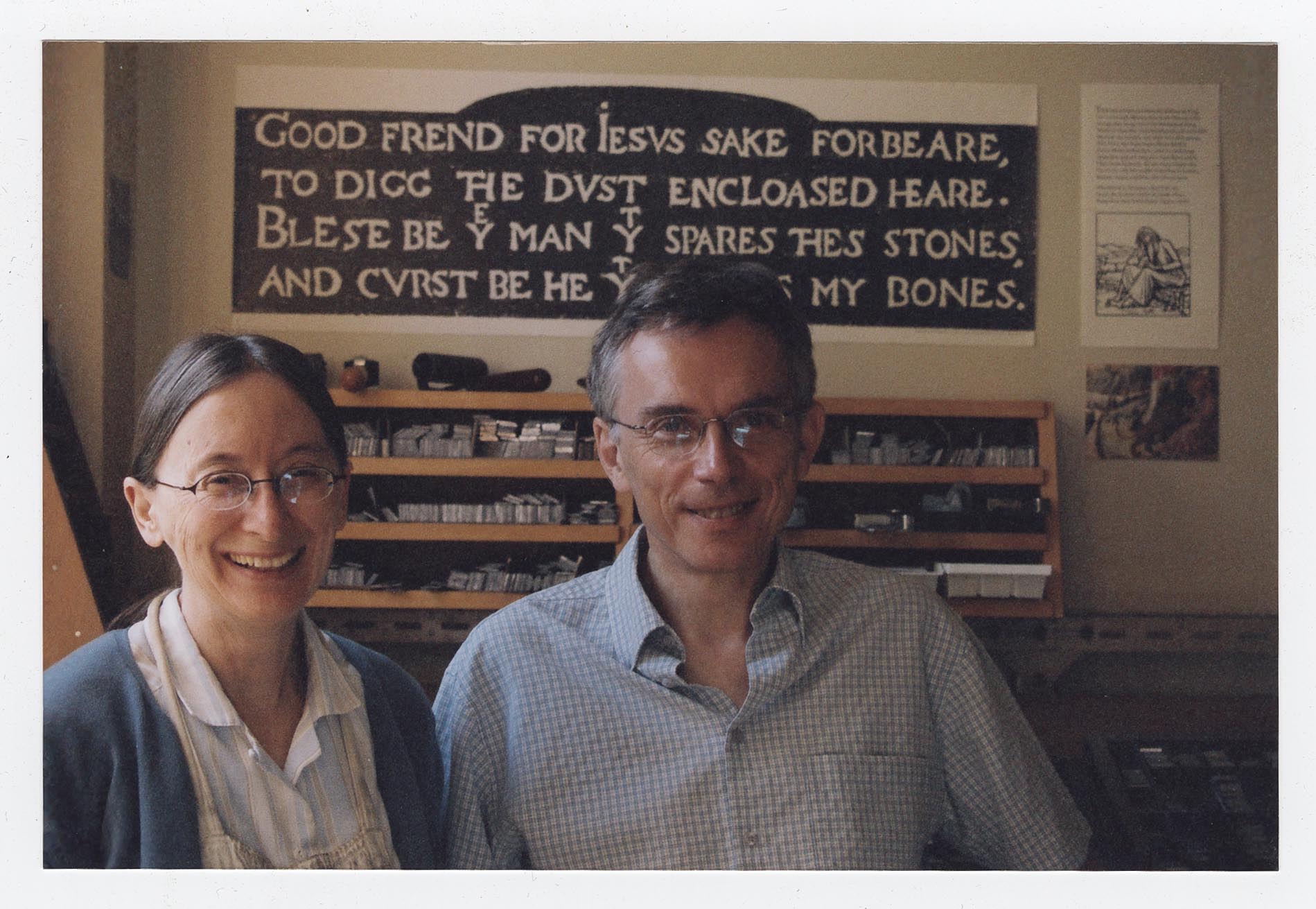

Locks’ Press is a unique partnership between two apparently opposite but actually complementary imaginations, one verbal and the other visual. Since Fred and Margaret Lock established their press in 1978, they have pursued a goal which commercial publishers would find incongruous, even absurd: scholarly publishing combined with original illustration. Fred Lock

Locks’ Press is a unique partnership between two apparently opposite but actually complementary imaginations, one verbal and the other visual. Since Fred and Margaret Lock established their press in 1978, they have pursued a goal which commercial publishers would find incongruous, even absurd: scholarly publishing combined with original illustration. Fred Lock  provides linguistic and editorial expertise, while Margaret Lock’s skills are design and artistic ability. In the first twenty-five years of the press, they have published about fifty imprints (books, pamphlets, and broadsides), all showing the intense personal involvement of the proprietors.

provides linguistic and editorial expertise, while Margaret Lock’s skills are design and artistic ability. In the first twenty-five years of the press, they have published about fifty imprints (books, pamphlets, and broadsides), all showing the intense personal involvement of the proprietors.

Locks’ Press was originally established in Brisbane, Australia, where the Locks resided from 1974 to 1987. Their first book was published there in 1979. By 1987, when they moved to Canada, the Press had produced seven books.

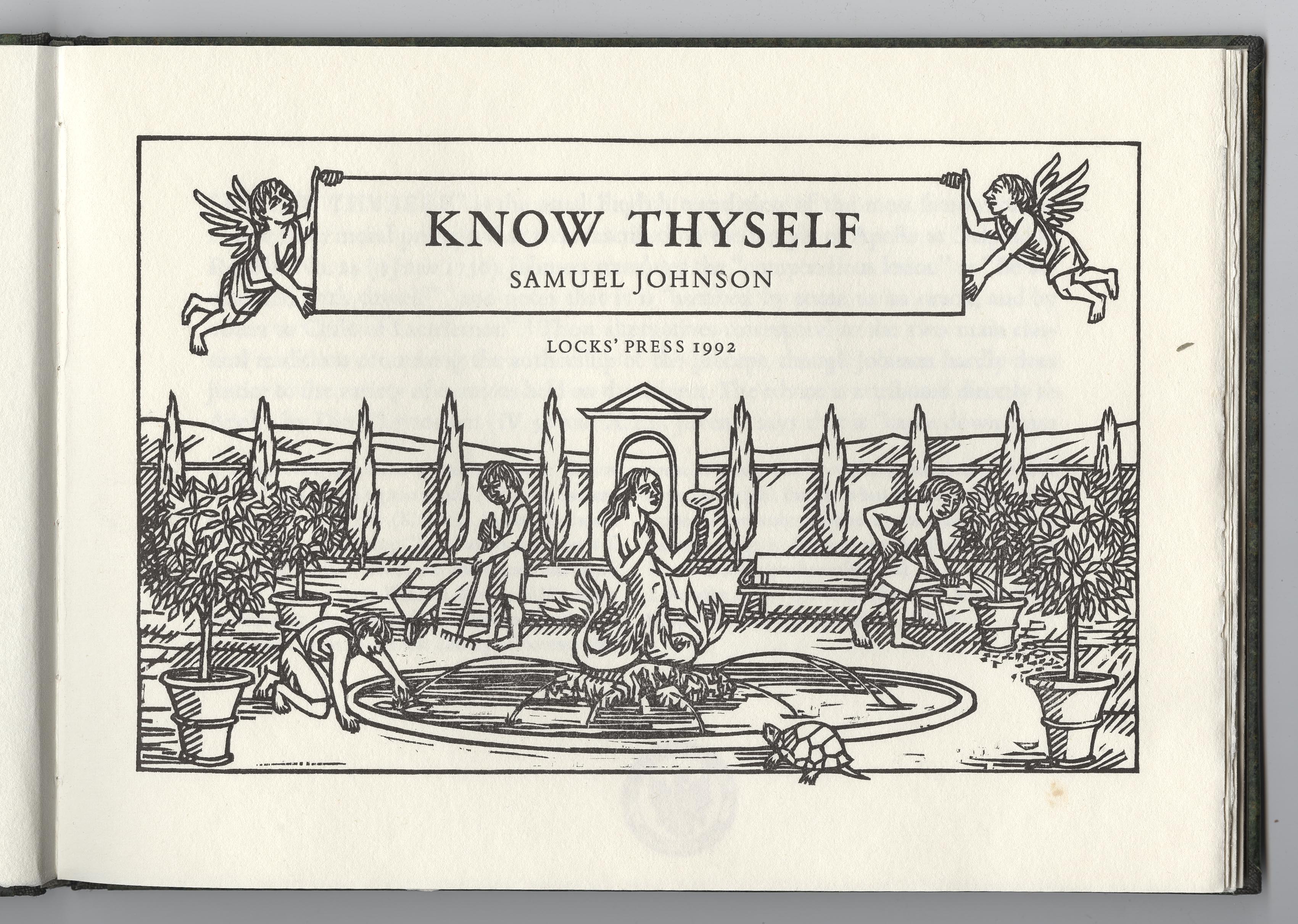

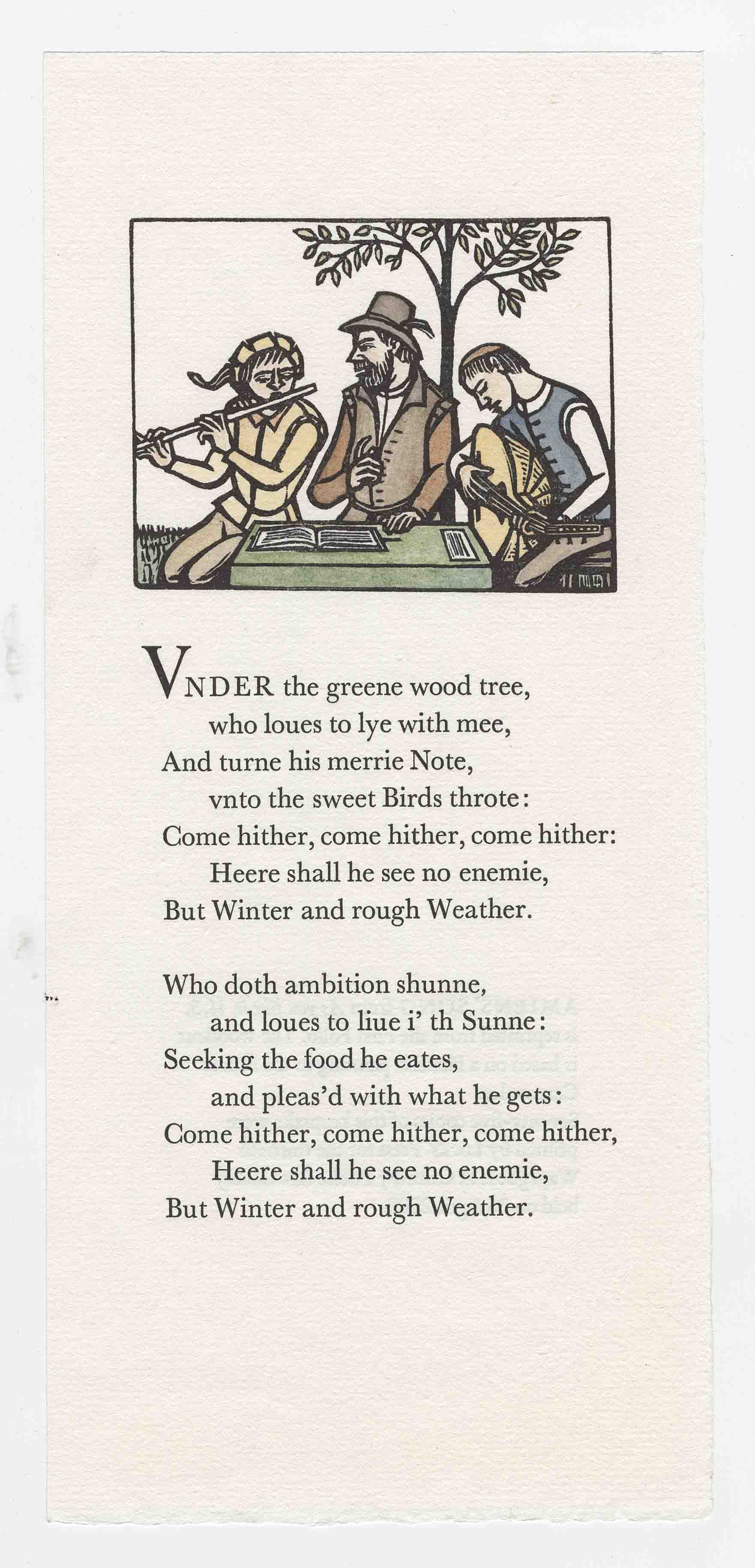

Avoiding contemporary literature, the Locks concentrate on works that were  written before 1900, choosing texts with a demonstrated longevity. Fred Lock particularly likes the classics and English medieval and eighteenth-century literature. The Press’ imprints from these periods include Women by Semonides of Amorgos (in the translation by Joseph Addison), the Balade de Bon Conseyl and December by Geoffrey Chaucer, and The Fountains, Know Thyself and Nature Sets her Gifts (an extract from Rasselas) by Samuel Johnson, as well as Johnson’s translation of Horace’s Odes 4.7. Margaret Lock looks for texts that she wants to illustrate, such as The Pobble Who Has No Toes by Edward Lear, Fame’s Trumpet (a collection of nursery rhymes), and How Much Land Does a Man Need? by Leo Tolstoy (in the translation by Louise and Alymer Maude).

written before 1900, choosing texts with a demonstrated longevity. Fred Lock particularly likes the classics and English medieval and eighteenth-century literature. The Press’ imprints from these periods include Women by Semonides of Amorgos (in the translation by Joseph Addison), the Balade de Bon Conseyl and December by Geoffrey Chaucer, and The Fountains, Know Thyself and Nature Sets her Gifts (an extract from Rasselas) by Samuel Johnson, as well as Johnson’s translation of Horace’s Odes 4.7. Margaret Lock looks for texts that she wants to illustrate, such as The Pobble Who Has No Toes by Edward Lear, Fame’s Trumpet (a collection of nursery rhymes), and How Much Land Does a Man Need? by Leo Tolstoy (in the translation by Louise and Alymer Maude).

As editor, Fred Lock decides which edition to use as copy text; this is always recorded in the colophon. Original spelling and punctuation are closely followed. For some medieval English poems, this entails using the obsolete letters yogh and thorn, and a minimum of capitalization. The unusual phonetic spelling encourages readers to sound out the words in their heads, which slows the rate at which they read and encourages them to pay attention to the meaning. In the case of Five Letters from Jane Austen to Her Sister Cassandra, 1813, reproducing the spelling and punctuation used by Austen brings readers a little closer to imagining her voice and mood.

As editor, Fred Lock decides which edition to use as copy text; this is always recorded in the colophon. Original spelling and punctuation are closely followed. For some medieval English poems, this entails using the obsolete letters yogh and thorn, and a minimum of capitalization. The unusual phonetic spelling encourages readers to sound out the words in their heads, which slows the rate at which they read and encourages them to pay attention to the meaning. In the case of Five Letters from Jane Austen to Her Sister Cassandra, 1813, reproducing the spelling and punctuation used by Austen brings readers a little closer to imagining her voice and mood.

Fred Lock has written introductions or colophon notes for the books and broadsides and has completed translations for about one third of the items  printed at the press. Few private presses have printed such a range of texts in translation. Seven are from Middle English, and six from Latin, the latter including texts from classical times to the eighteenth century. Some authors, such as Justus Lipsius and Sannazaro, are now obscure, but Lock believes that their work still merits attention. He has also translated from German (Winckelmann’s Advice on Looking at Greek Sculpture, and the fifteenth-century carol, Es Ist ein Ros’), Greek (Hymn to Hephaistos), and Provençal (William of Poitier’s Poem about Nothing). The translations are precise and thoughtful. For the work titled Charles XII, he translated a propaganda piece and a previously unpublished poem about the Swedish king, both from a manuscript formerly belonging to Jonathan Swift, now in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. Johnson’s Know Thyself was translated from a manuscript version of the poem formerly belonging to Hester Thrale, now at Yale. Lock’s version retains the original metre (hexameters) of the Latin.

printed at the press. Few private presses have printed such a range of texts in translation. Seven are from Middle English, and six from Latin, the latter including texts from classical times to the eighteenth century. Some authors, such as Justus Lipsius and Sannazaro, are now obscure, but Lock believes that their work still merits attention. He has also translated from German (Winckelmann’s Advice on Looking at Greek Sculpture, and the fifteenth-century carol, Es Ist ein Ros’), Greek (Hymn to Hephaistos), and Provençal (William of Poitier’s Poem about Nothing). The translations are precise and thoughtful. For the work titled Charles XII, he translated a propaganda piece and a previously unpublished poem about the Swedish king, both from a manuscript formerly belonging to Jonathan Swift, now in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. Johnson’s Know Thyself was translated from a manuscript version of the poem formerly belonging to Hester Thrale, now at Yale. Lock’s version retains the original metre (hexameters) of the Latin.

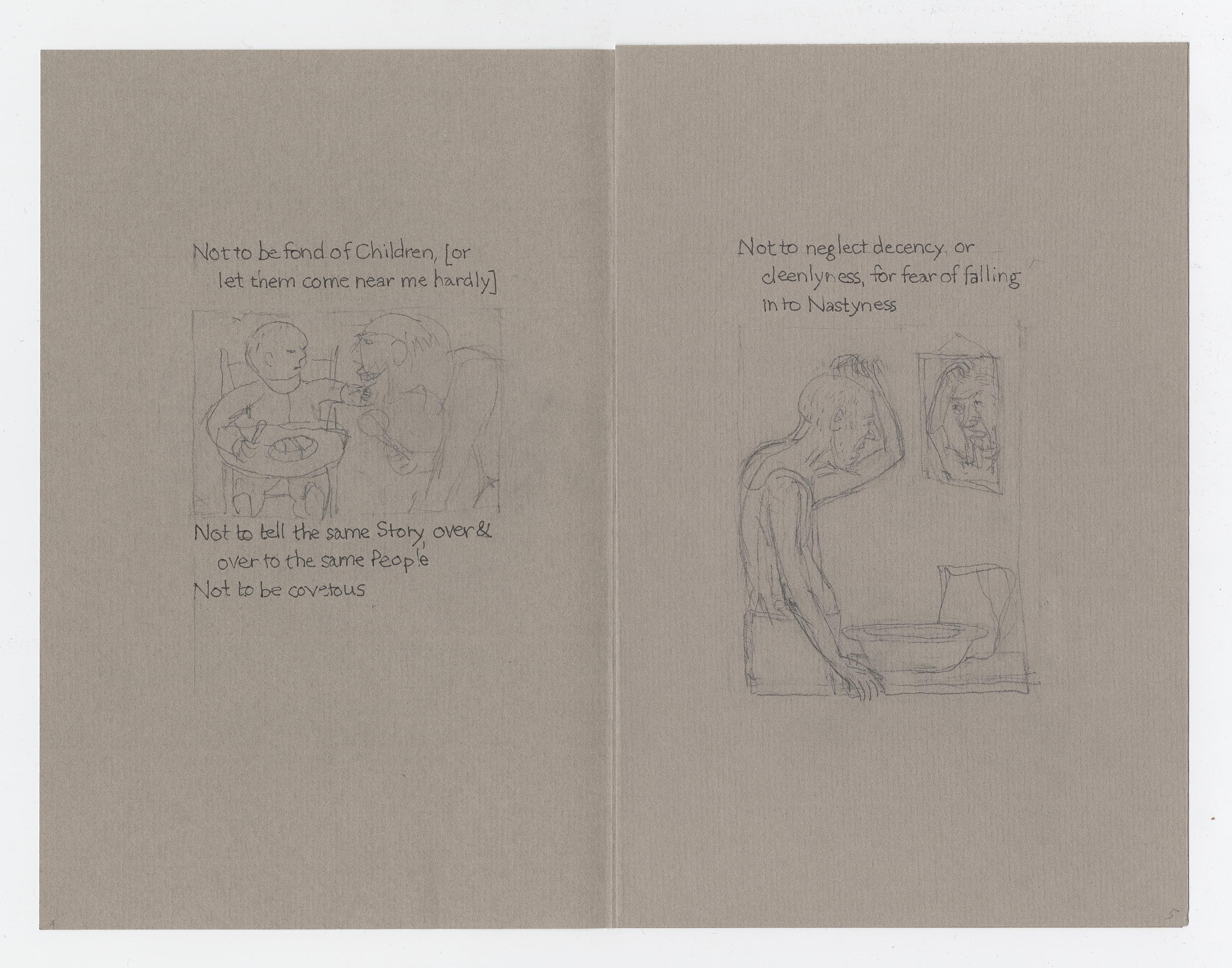

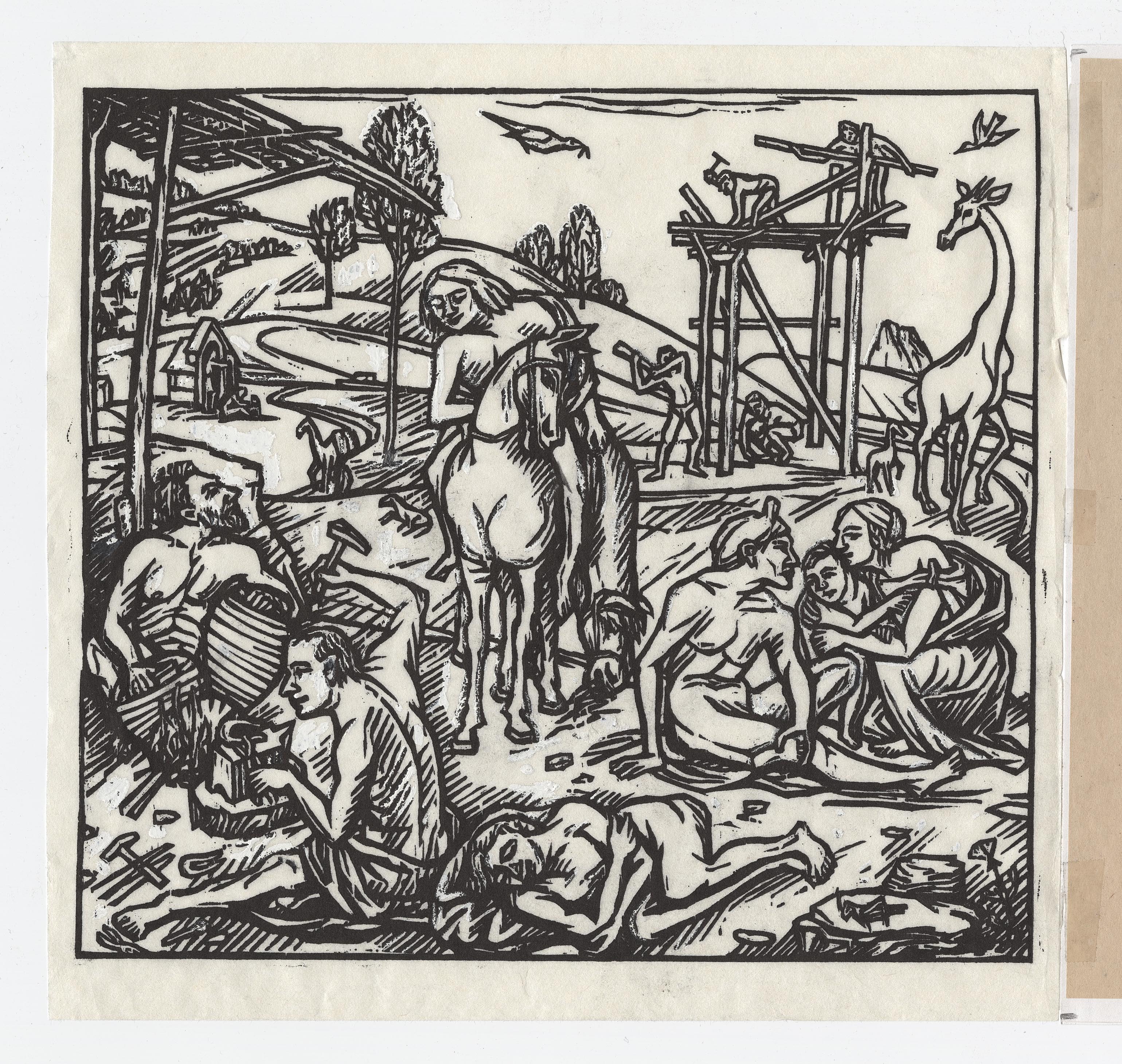

While the choice of texts is idiosyncratic, Margaret Lock’s illustrations and typographic taste are responsible for the distinctive visual character of Locks’ Press books. Most items from the press include her woodcuts. For the more scholarly books, their role is usually minor. In Know Thyself, the only decoration is the title page, with a garden scene to bring to mind a related piece of advice, this time from Candide: “il faut cultiver notre jardin”. Here, the garden of the soul is being swept and watered. The mermaid looking in the mirror symbolizes self-study; the turtle, slow and steady progress. For The Fountains, How Much Land Does a Man Need? and King Orfeo, Margaret Lock has visualized the narratives in a straightforward way.

While the choice of texts is idiosyncratic, Margaret Lock’s illustrations and typographic taste are responsible for the distinctive visual character of Locks’ Press books. Most items from the press include her woodcuts. For the more scholarly books, their role is usually minor. In Know Thyself, the only decoration is the title page, with a garden scene to bring to mind a related piece of advice, this time from Candide: “il faut cultiver notre jardin”. Here, the garden of the soul is being swept and watered. The mermaid looking in the mirror symbolizes self-study; the turtle, slow and steady progress. For The Fountains, How Much Land Does a Man Need? and King Orfeo, Margaret Lock has visualized the narratives in a straightforward way.

Before she draws the illustrations, Margaret Lock researches architecture, furniture, dress, and other details contemporary with the text. A false representation of a period can be jarring and destroy the reader’s trust in the illustrator. However, the style of the woodcuts remains modern; she does not try to make illustrations for a medieval text look like those from a medieval manuscript. Occasionally, when a text is comic or when she wants to emphasize its universal relevance, she deliberately includes anachronisms or interprets an older text with figures in modern dress. For one pamphlet, an extract from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, she employed purely typographic means (coloured shapes and large wooden type) rather than woodcuts. This was not only appropriate to the text, but also to the commemorative nature of the pamphlet, which honoured printer and teacher Bill Poole (1923-2001), who had a particular love of such wooden letters. The pamphlet was part of an anthology produced for the annual book arts fair known as Wayzgoose, originated by Poole in 1979 and held in Grimsby, Ontario, each spring.

Before she draws the illustrations, Margaret Lock researches architecture, furniture, dress, and other details contemporary with the text. A false representation of a period can be jarring and destroy the reader’s trust in the illustrator. However, the style of the woodcuts remains modern; she does not try to make illustrations for a medieval text look like those from a medieval manuscript. Occasionally, when a text is comic or when she wants to emphasize its universal relevance, she deliberately includes anachronisms or interprets an older text with figures in modern dress. For one pamphlet, an extract from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, she employed purely typographic means (coloured shapes and large wooden type) rather than woodcuts. This was not only appropriate to the text, but also to the commemorative nature of the pamphlet, which honoured printer and teacher Bill Poole (1923-2001), who had a particular love of such wooden letters. The pamphlet was part of an anthology produced for the annual book arts fair known as Wayzgoose, originated by Poole in 1979 and held in Grimsby, Ontario, each spring.

Locks’ Press is a part-time occupation. Whereas books can take more than a year to plan and execute, broadsides allow for quicker publication. This does not mean that the text and woodcuts for broadsides are less thoughtful. Some woodcuts allude to the subject of the text and establish a mood; others act as meditation pieces. Margaret Lock pairs a woodcut of a specific painting (or part of it) with a text that she feels resonates with it. Ideally, the viewer/reader will always remember the meaning conveyed by both, with the text bringing the picture and its message to mind, and vice versa. Occasionally, the text encourages the viewer to reassess the painting.

Locks’ Press is a part-time occupation. Whereas books can take more than a year to plan and execute, broadsides allow for quicker publication. This does not mean that the text and woodcuts for broadsides are less thoughtful. Some woodcuts allude to the subject of the text and establish a mood; others act as meditation pieces. Margaret Lock pairs a woodcut of a specific painting (or part of it) with a text that she feels resonates with it. Ideally, the viewer/reader will always remember the meaning conveyed by both, with the text bringing the picture and its message to mind, and vice versa. Occasionally, the text encourages the viewer to reassess the painting.

The Locks do not expect to earn money from publishing, nor is either of them prepared to spend much effort on marketing and distribution. They have a few regular customers, including one or two specialist bookstores. Every year they attend book arts fairs, including Wayzgoose, as well as those organized by the printmaking department of the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto, and by the Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild. However, these events are only incidentally about sales; printers and book artists attend in order to keep in touch with each other, assess everyone else's work, and show off their own.

The Locks do not expect to earn money from publishing, nor is either of them prepared to spend much effort on marketing and distribution. They have a few regular customers, including one or two specialist bookstores. Every year they attend book arts fairs, including Wayzgoose, as well as those organized by the printmaking department of the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto, and by the Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild. However, these events are only incidentally about sales; printers and book artists attend in order to keep in touch with each other, assess everyone else's work, and show off their own.

Private presses are inherently individualistic, reflecting the interests and personality of their proprietors. Locks’ Press is known for fine printing, quirky illustrations, and its eclectic choice of often obscure texts. This combination is the result of a happy concordia discors between the ideas and imaginations of its two founders.

“Canadian Private Presses” website, Library and Archives Canada

http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/206/301/lac-bac/presses-ef/presses/index-e… (accessed 11 May 2009)

Ink Paper Lead, Board Leather Thread: An Exhibition of Hand-printed Books and Fine Bindings by The Loving Society of Letterpress Printers and The Binders of Infinite Love: Wesley W. Bates, Reg Beatty, Stan Bevington, Margaret Lock, David Moyer, William Rueter, Alan Stein, George Walker, Shaunie and Brian Young. With an introduction by Anne Sutherland. Toronto: Loving Society of Letterpress Printers and The Binders of Infinite Love, 2002. [exhibition catalogue]

Lock, Margaret. "Locks' Press, 1979-2006." The Private Library. 5th series: 10.1 (Spring 2007) 2-26.

Speller, Randall. "Betwixen Adamauntes Two," Canadian Notes and Queries, 58 (November 2000) 3-11.

Locks’ Press fonds, McMaster University

![Letter from Duncan C. Scott (Royal Society of Canada) to [Lorne] Pierce (Ryerson Press), 21 February 1944](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01141.jpg?itok=JNiUpkki)

![Sample of the proposed title page for the Canadian edition of In the Village of Viger, [1945?]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01142.jpg?itok=3c6HKmTd)

![Telegram from [Elise] Scott to the Ryerson Press, 25 October 1949 re Selected Poems of Duncan Campbell Scott](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01143.jpg?itok=7kMJVdTK)

![Gladys E. Neale interview by Roy MacSkimming [audio interview], 23 September 1998](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/mic-50-128x128-neale.png?itok=6xKk_2W2)

![Robin Farr interview by Roy MacSkimming [audio interview], 21 October 1998](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/mic-50-128x128-farr.png?itok=zhctCdoQ)

![Francess Halpenny interview by Roy MacSkimming [audio interview], 23 October 1998](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/mic-50-128x128-halpenny.png?itok=1D34P1by)

![John Metcalf interview by Roy MacSkimming [audio interview], 2 November 1999](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/mic-50-128x128-metcalf.png?itok=u8OfrP6W)

![Valerie Hussey interview by Roy MacSkimming [audio interview], 19 May 1999](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/mic-50-128x128-hussey.png?itok=W-6qtqeI)

![James Douglas interview by Roy MacSkimming [audio interview], 4 February 1998](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/mic-50-128x128-douglas.png?itok=RBNQFtQc)