The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float – The Happy Adventure of Farley Mowat and Jack McClelland

Donna Thomson, McMaster University

Farley Mowat was first published at the early age of 13 when he submitted a weekly column about bird life, titled “Birds of the Season,” to the Saturday children’s supplement Prairie Pals of the Saskatoon Star Phoenix. Mowat was paid five dollars for his column, which ran from March to May 1936. His early career as an author ended abruptly when he penned a piece describing the underwater mating habits of the ruddy duck. Despite this inauspicious beginning, Mowat is currently one of the most widely

Farley Mowat was first published at the early age of 13 when he submitted a weekly column about bird life, titled “Birds of the Season,” to the Saturday children’s supplement Prairie Pals of the Saskatoon Star Phoenix. Mowat was paid five dollars for his column, which ran from March to May 1936. His early career as an author ended abruptly when he penned a piece describing the underwater mating habits of the ruddy duck. Despite this inauspicious beginning, Mowat is currently one of the most widely  read and best-known Canadian writers. He has over forty books to his name, which have been published in translations in over twenty-four languages, in more than sixty countries. Although Mowat’s skill as a storyteller is legendary, some of this credit must be given to his publisher Jack McClelland. Promoting Canadian talent was McClelland’s forte and passion. Pierre Berton, who became a McClelland & Stewart (M&S) author in 1954, told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 2004 at the time of McClelland's death, that “If you got a book with Jack McClelland you could be sure it would get publicized. He pushed books and he knew how to do it. He was brilliant.” Indeed, McClelland’s motto was: “I publish authors, not books.” In a manner that echoed the words of his father, who had founded the company, he proudly professed: “Canadian authors are the specialty of our house.”

read and best-known Canadian writers. He has over forty books to his name, which have been published in translations in over twenty-four languages, in more than sixty countries. Although Mowat’s skill as a storyteller is legendary, some of this credit must be given to his publisher Jack McClelland. Promoting Canadian talent was McClelland’s forte and passion. Pierre Berton, who became a McClelland & Stewart (M&S) author in 1954, told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in 2004 at the time of McClelland's death, that “If you got a book with Jack McClelland you could be sure it would get publicized. He pushed books and he knew how to do it. He was brilliant.” Indeed, McClelland’s motto was: “I publish authors, not books.” In a manner that echoed the words of his father, who had founded the company, he proudly professed: “Canadian authors are the specialty of our house.”

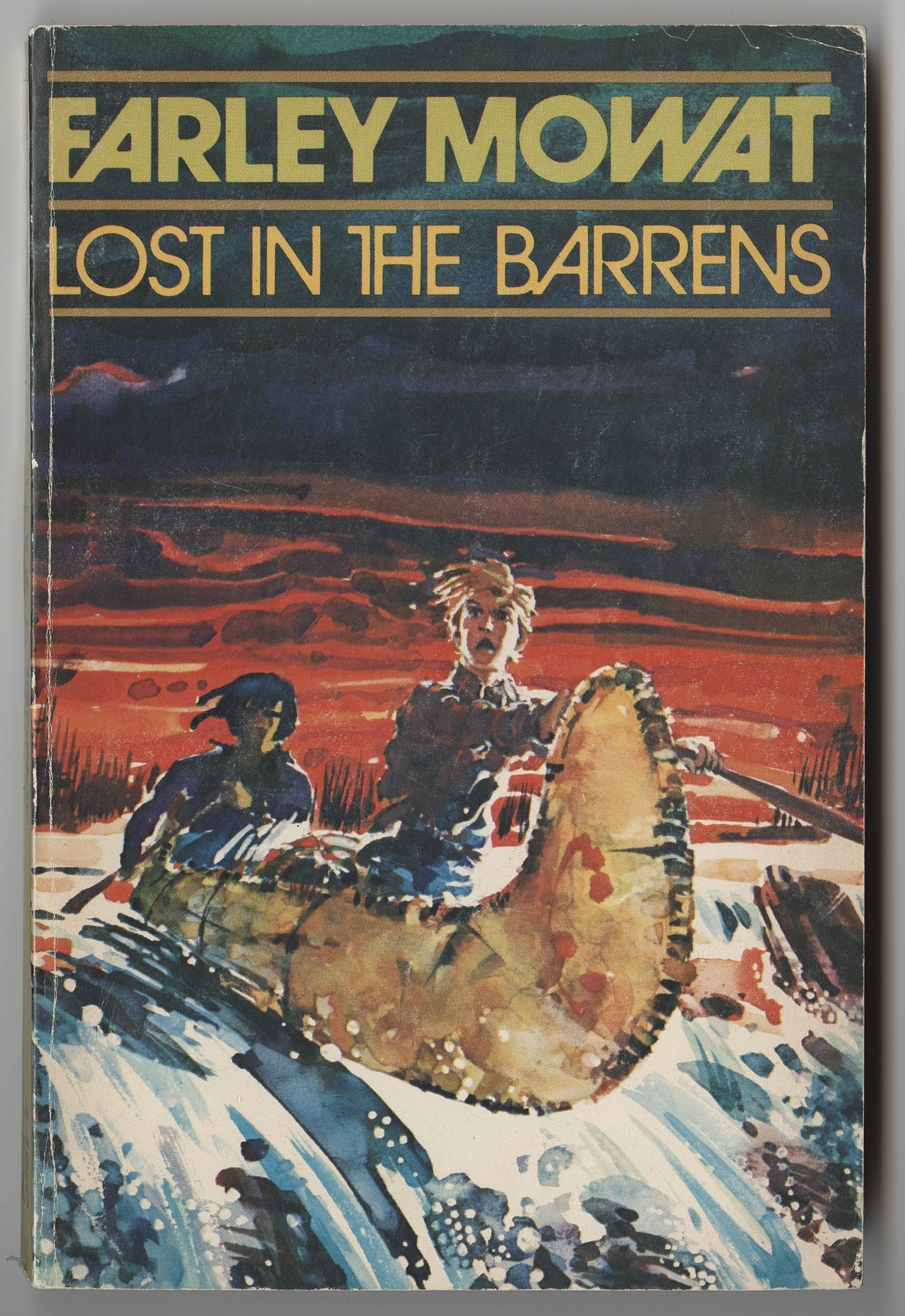

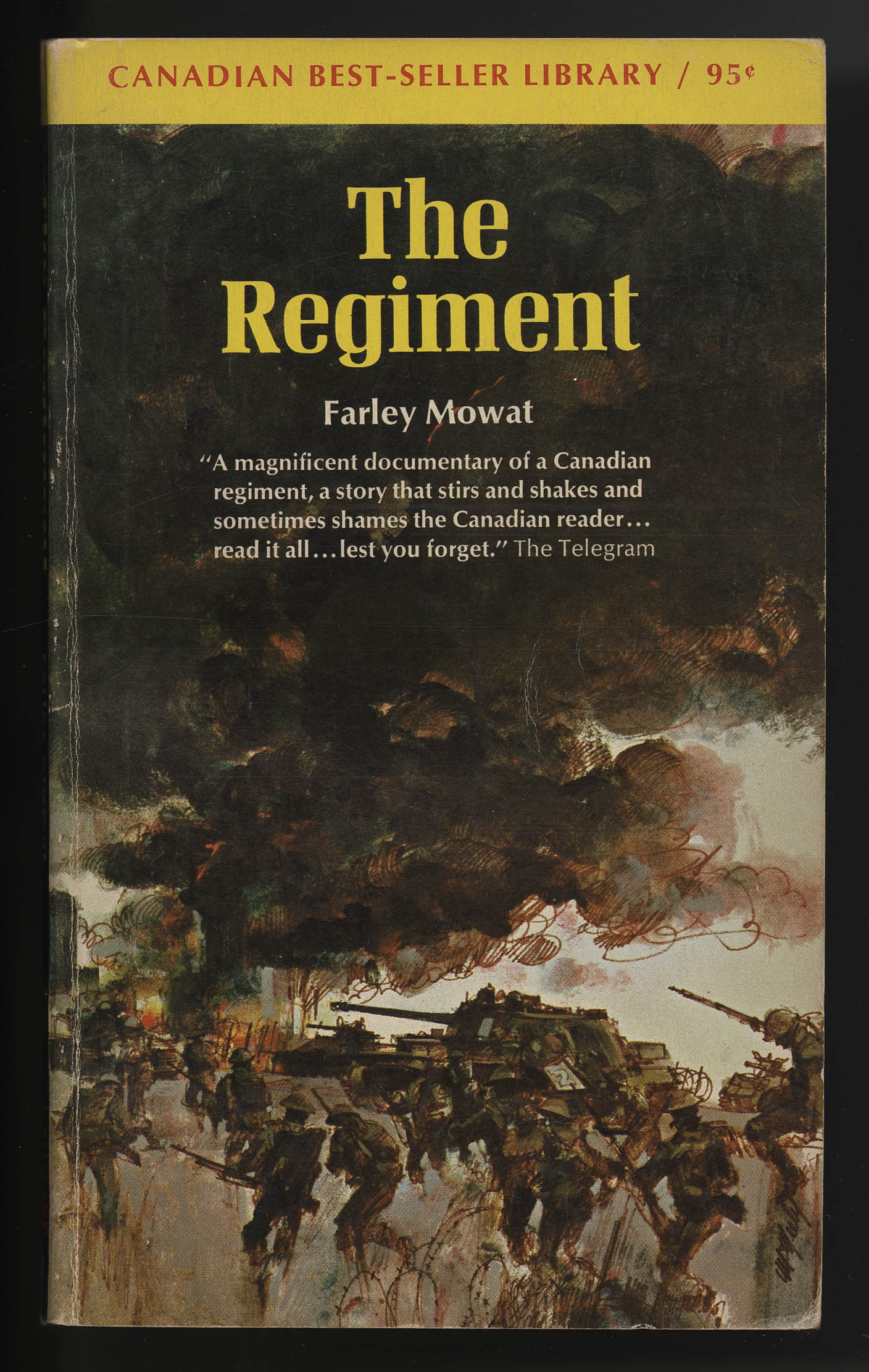

Mowat became an M&S author in 1955 with his second book, The Regiment. Mowat said that McClelland talked him into turning down a British offer and convinced him to publish with M&S instead. "I allowed myself to be talked into it and I'm so God damned glad I did, because as a result of his determination I have published continuously in Canada. I've remained a Canadian all my life. I've written about my country all my life and it's almost entirely due to Jack's influence.”

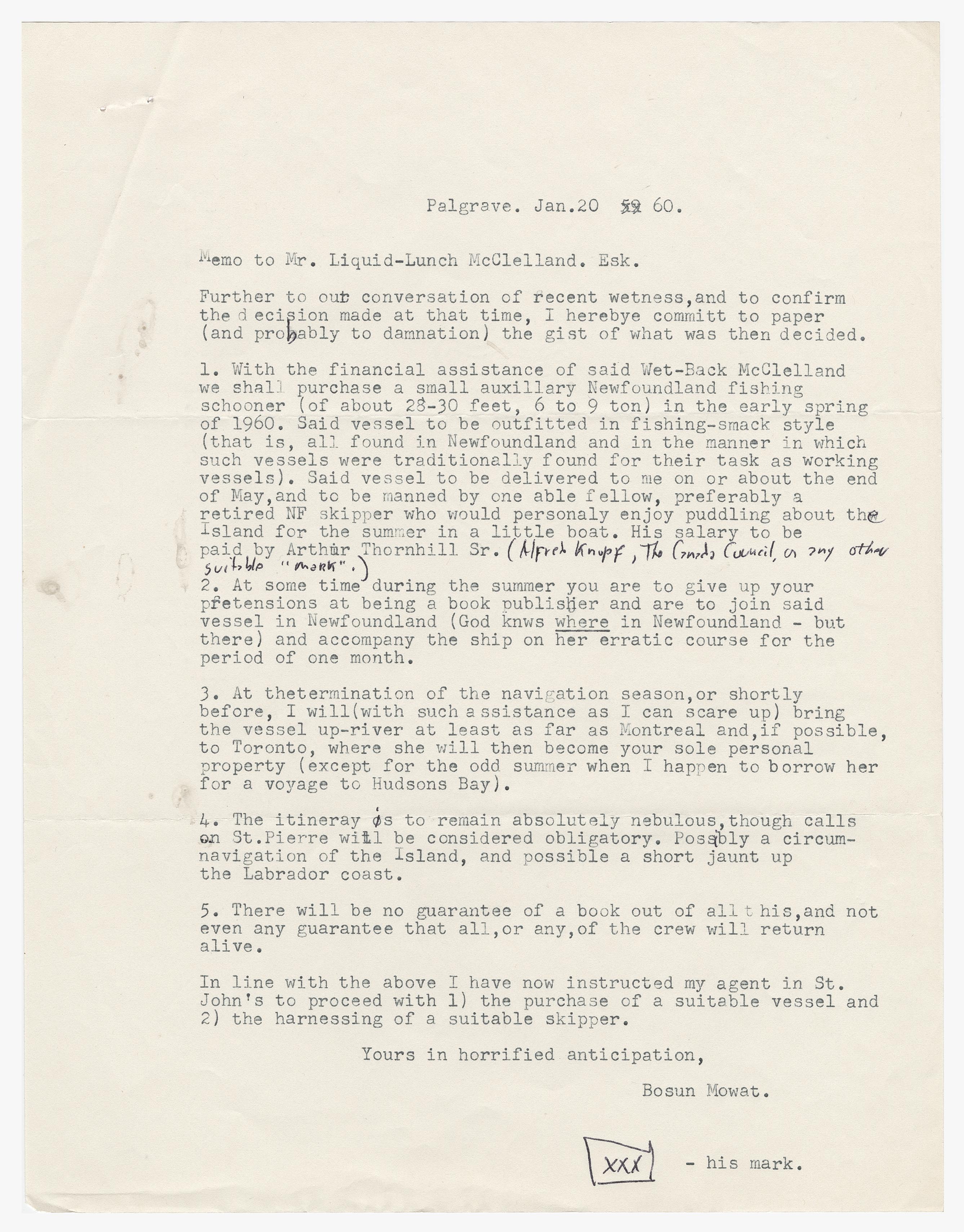

McClelland’s and Mowat’s relationship went much further than publishing, as the two became close personal friends. On an evening of revelry, they made a plan to escape their day-to-day routine, buy a boat, and seek adventure. Mowat quickly acted on this scheme, and in a letter to McClelland, wrote:

Memo to Mr. Liquid-Lunch McClelland. Esk.[sic?], Further to our conversation of recent wetness, and to confirm the decision made at that time, I herebye [sic] commit to paper (and probably to damnation) the gist of what was then decided.1.With the financial assistance of said Wet-Back McClelland we shall purchase a small auxiliary Newfoundland fishing schooner (of about 28-30 feet, 6 to 9 ton) in the early spring of 1960. Said vessel to be outfitted in fishing-smack style…

2.At some time during the summer you are to give up your pretensions at being a book publisher and are to join said vessel in Newfoundland… and accompany the ship on her erratic course for the period of one month...

Yours in horrified anticipation, Bosun Mowat.

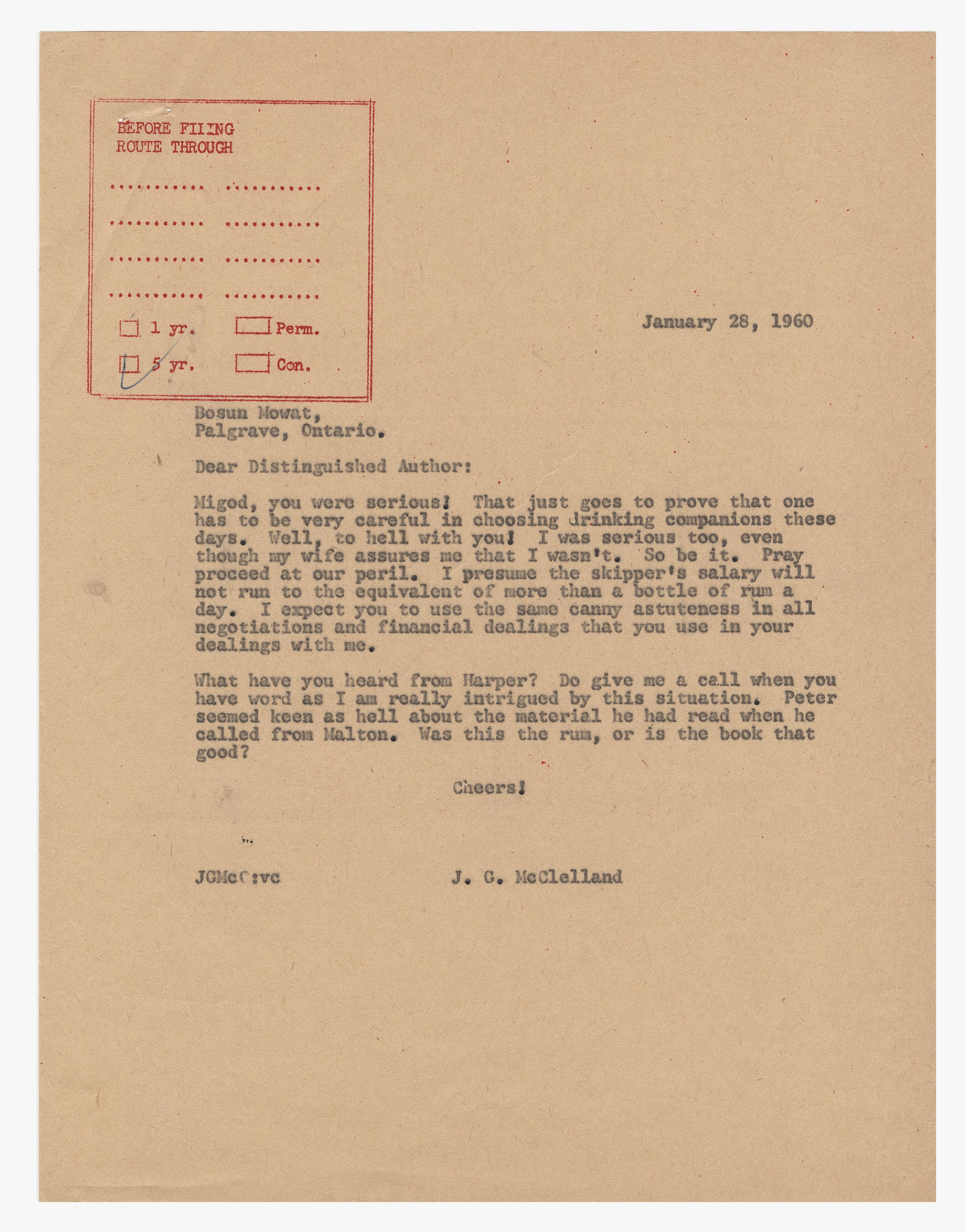

McClelland responded, perhaps slightly less enthusiastically:

Bosun Mowat, Palgrave, Ontario.

Dear Distinguished Author:

Migod, you were serious! That just goes to prove that one has to be very careful in choosing drinking companions these days. Well, to hell with you! I was serious too, even though my wife assures me that I wasn’t. So be it. Pray proceed at our peril. I presume the skipper’s salary will not run to the equivalent of more than a bottle of rum a day. I expect you to use the same canny astuteness in all negotiations and financial dealings that you use in your dealings with me …

Mowat did proceed, and travelled to Newfoundland to purchase a boat to be owned jointly with McClelland.

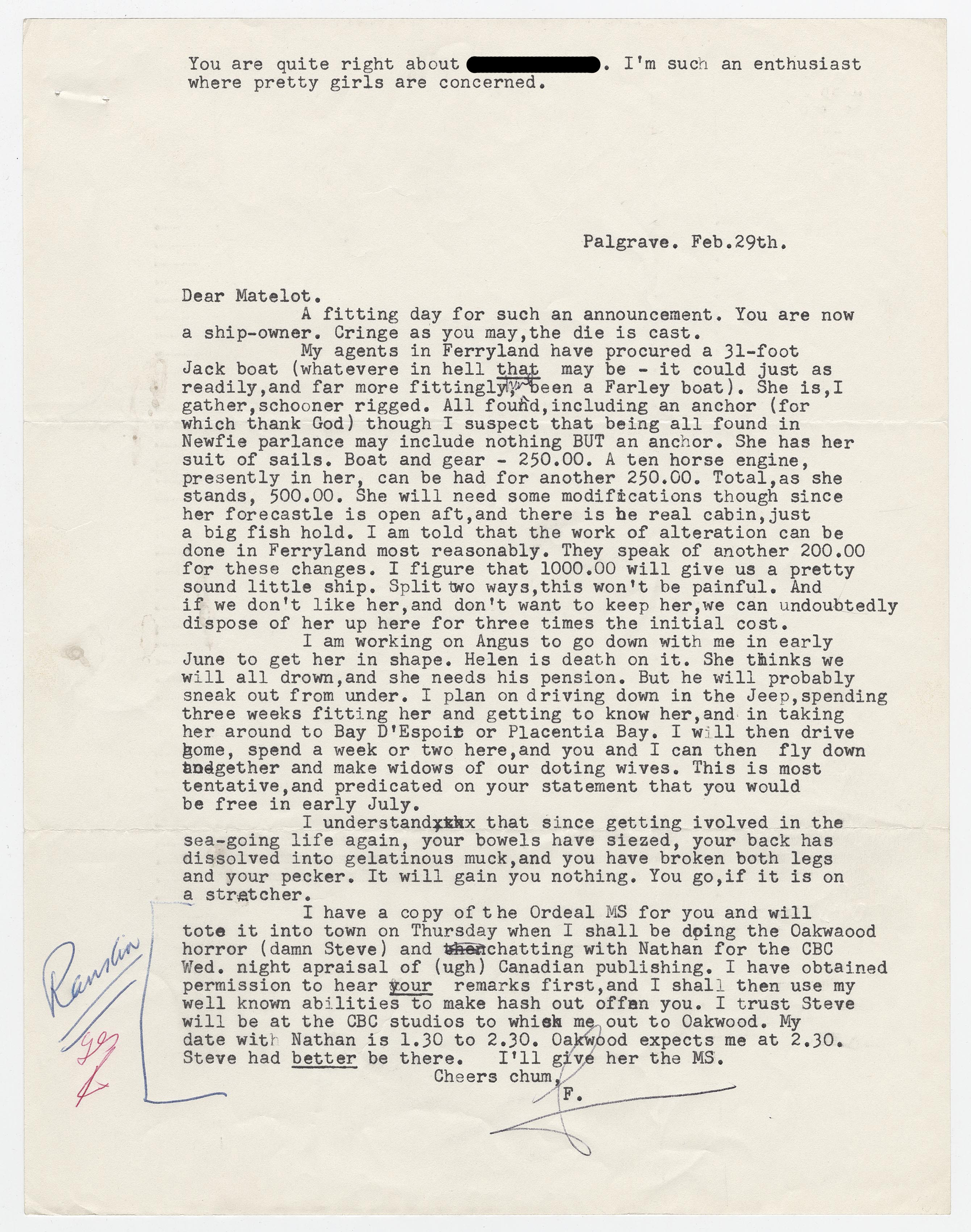

Dear Matelot.

A fitting day for such an announcement. You are now a ship-owner. Cringe as you may, the die is cast.

My agents in Ferryland have procured a 31-foot Jack boat (whatevere [sic] in hell that may be – it could just as readily, and far more fittingly have been a Farley Boat). She is, I gather, schooner rigged. All found, including an anchor …

McClelland replied: “Dear Farley: Sorry we missed you yesterday. The die is not cast. No one, repeat no one, not even Mowat, buys a boat without seeing it. So take care. This one sounds intriguing though and is probably the right answer. I consider it most appropriate that it be a jack-boat, and am appalled that you are not familiar with this type of craft.”

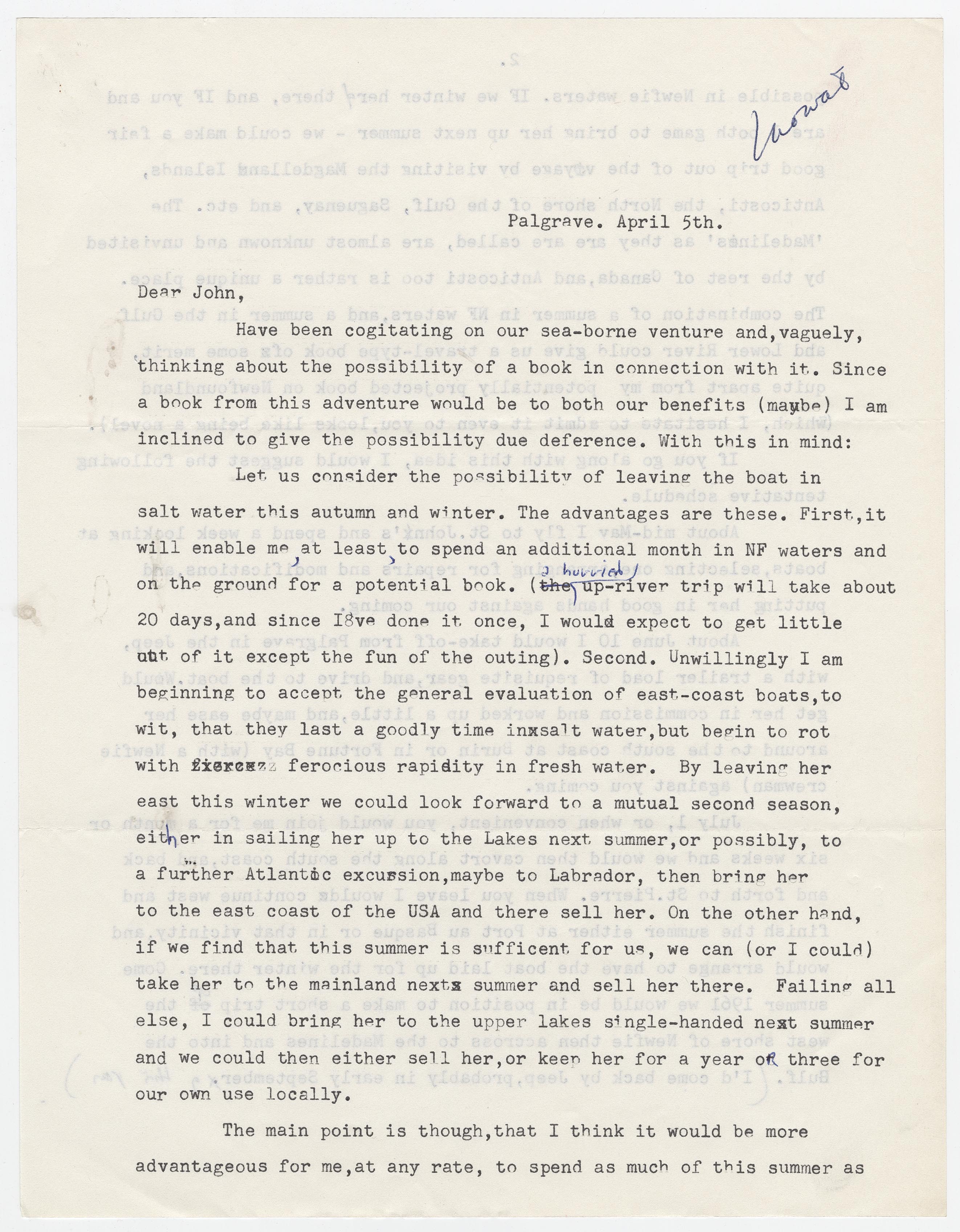

The Happy Adventure — a 31 ft. schooner, with a mind of her own — was the result. From the start of the boat buying, Mowat had ulterior motives. In a letter to McClelland, he wrote: “Have been cogitating on our sea-borne venture and, vaguely, thinking about the possibility of a book in connection with it. Since a book from this adventure would be to both our benefits (maybe) I am inclined to give the possibility due deference …”

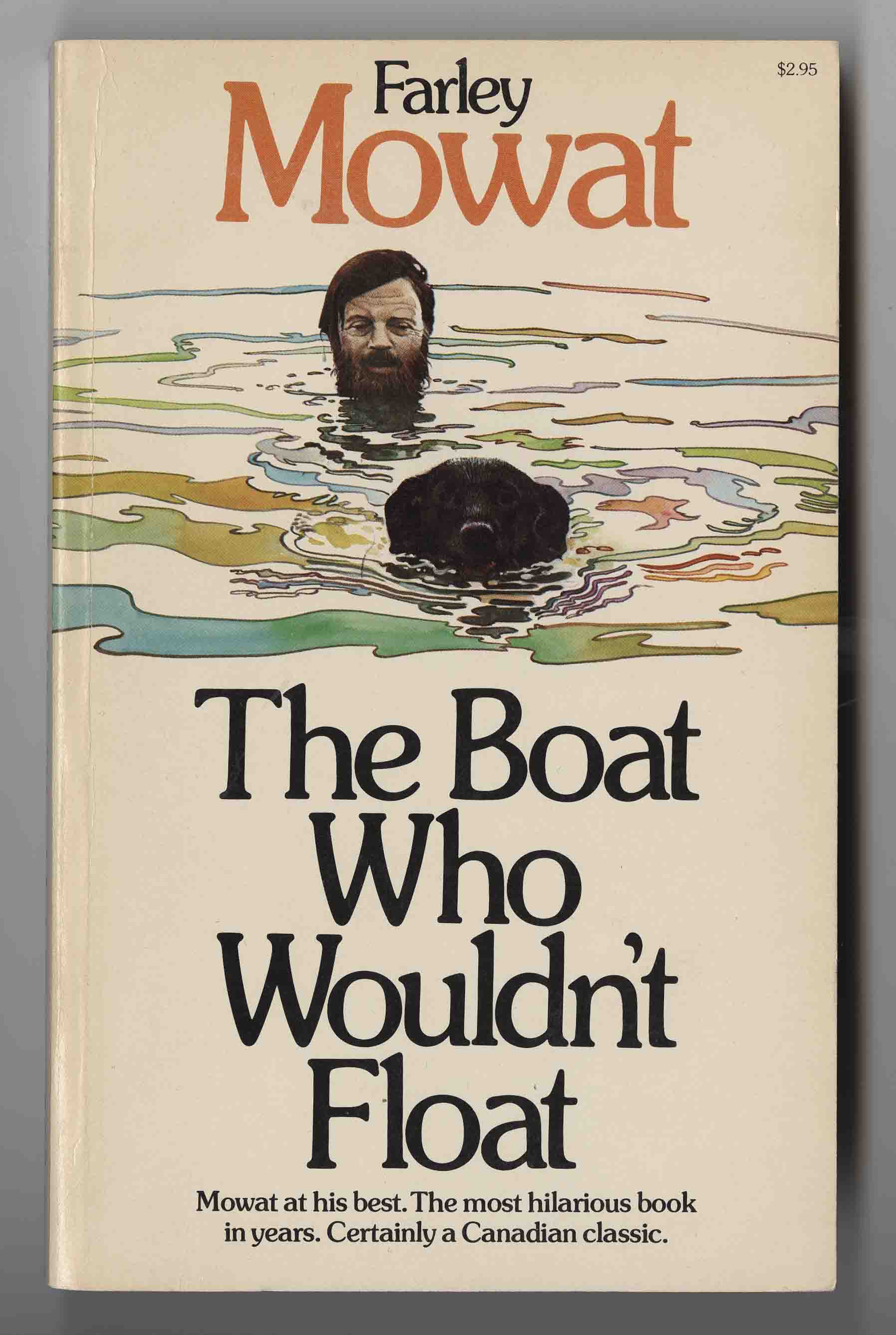

The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float is Mowat’s account of the results of the co-ownership. It is a portrayal of the comic misadventures of a schooner in a frequent state of sinking (eight times), running aground, or simply not responding to Mowat’s controls at the helm. McClelland was often seconded from his publishing house in Toronto to aid his friend. He stepped in and took control, or tried to do so. Mowat wrote in The Boat Who Wouldn't Float that the Happy Adventure:

remained suspicious of my motives, and distinctly unco-operative. After two false starts … I sent an urgent SOS to Jack McClelland. Jack, ever loyal, flew to Gander, chartered a float plan, and joined me. Then he proceeded to bring Happy Adventure to Heel. Jack can be a driver when his dander is up, taking no account of risks to life and limb. He made it very clear to the little schooner that she was either going to go to Burgeo, or she was going to go to the bottom of the sea in deep, deep water from whose icy embrace she could never again hope to emerge. I don’t know how she felt about his do-or-die attitude, but he scared the living daylights out of me!

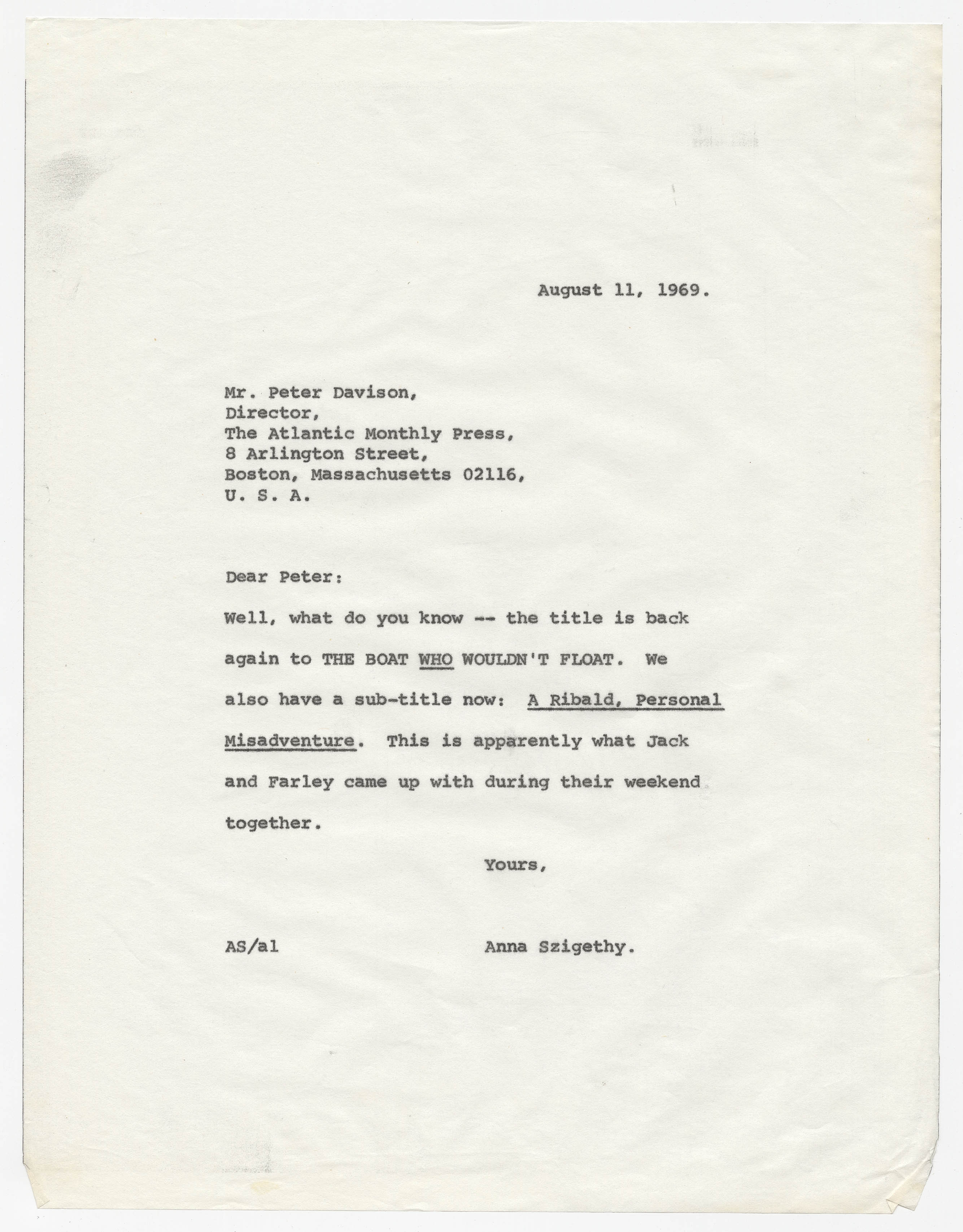

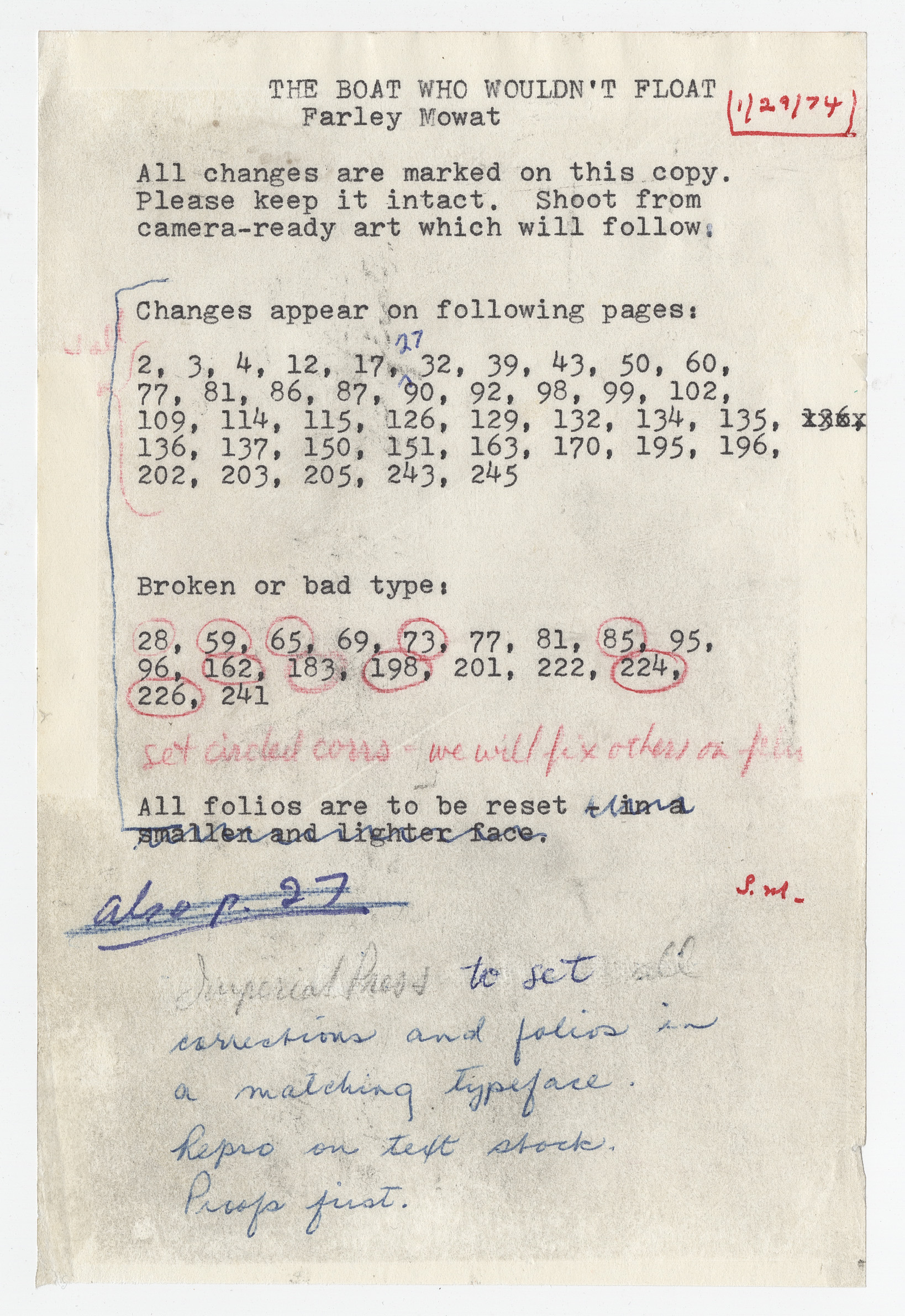

The schooner, Happy Adventure is the true heroine of this tale. When the book was sent to be proofread prior to publishing, much discussion ensued about its title. Peter Davison of the Atlantic Monthly Press wrote to M&S editor Anna Szigethy on 28 July 1969: “Do persuade Farley that a boat is a that, not a who. THE DOG WHO WOULDN’T BE is not a precedent for this book, and Itchy, tell him, is no Mutt.”

Mowat agreed to this revision, but the title was changed back to the original.

Mowat agreed to this revision, but the title was changed back to the original.

August 11, 1969

Dear Peter:

Well, what do you know -- the title is back again to THE BOAT WHO

WOULDN’T FLOAT...This is apparently what Jack and Farley came up with

during their weekend together.

Yours, Anna Szigethy.

The Happy Adventure remained a ‘Who,” and by 1985 had been published by M&S in three editions as well as a school paperback issue. The book has become a Canadian classic and is still in print. In The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float, Mowat combines adventure, romance, and humour. He portrays the camaraderie of two men and their very different attitudes to life, and in doing so marks a tribute to his friend and publisher Jack McClelland. The Boat Who Wouldn’t Float is also an acknowledgement of Mowat’s comic skill as an author, as it won the Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal in 1970.

"Jack McClelland Dead at 81." Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Website, 15 June 2004. http://www.cbc.ca/arts/story/2004/06/15/jackarts040615.html

King, James. Farley. Toronto: HarperFlamingoCanada, 2002.

Mowat, Farley. The Boat Who Wouldn't Float. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1969.

Porter, Anna. Jack McClelland: The Publisher of Canadian Literature. Mexico: University of Guada, 1996.

Jack McClelland fonds, McMaster University

McClelland & Stewart Ltd. fonds, McMaster University

Farley Mowat fonds, McMaster University

!["Billy" Sunday : the man and his message, [1915]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000005.jpg?itok=5-pxPBhG)

!["Billy" Sunday : the man and his message, [1915]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000005-2.jpg?itok=ENb7n96W)