Lorne Pierce of the Ryerson Press and Vera Lysenko’s Men in Sheepskin Coats (1947): Resisting the “Red Scare”

Sandra Campbell, Carleton University

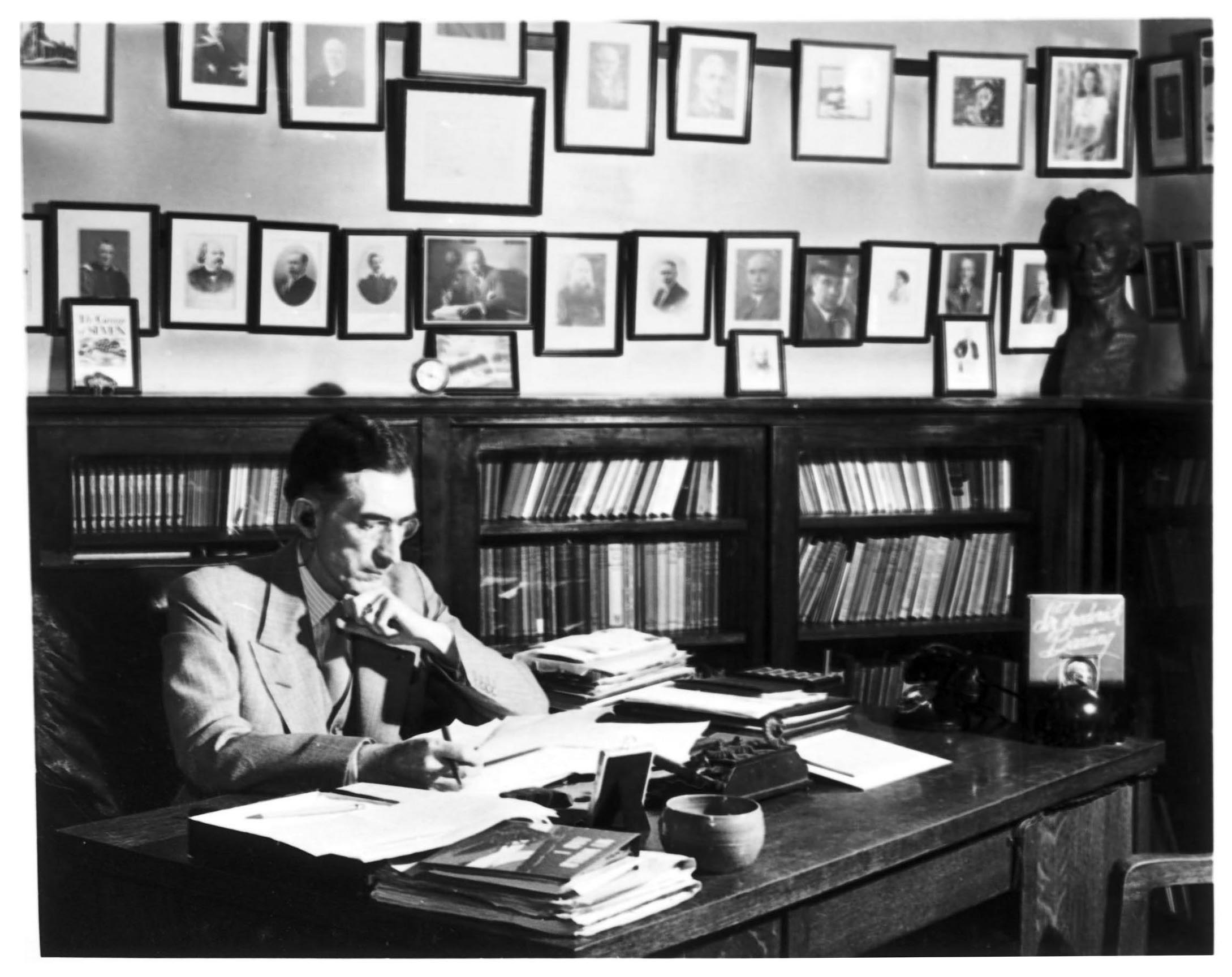

Lorne Pierce (1890-1961), editor of Ryerson Press from 1920 to 1960, was  arguably English Canada's most influential publisher in the period from Canada's coming-of-age after the First World War to the Quiet Revolution. He was determined, as he put it, to make Ryerson a "cultural mecca" for Canada and his desk a "sort of altar at which I serve ... [as one] very much concerned about the entire cultural life of Canada."

arguably English Canada's most influential publisher in the period from Canada's coming-of-age after the First World War to the Quiet Revolution. He was determined, as he put it, to make Ryerson a "cultural mecca" for Canada and his desk a "sort of altar at which I serve ... [as one] very much concerned about the entire cultural life of Canada."  These impulses were fostered by the spiritual emphasis of his stoutly Methodist upbringing in the eastern Ontario village of Delta, and from the idealism and patriotism he drank in at Queen's University (B.A. 1912) under philosopher John Watson and theologian William Jordan. Work as a Methodist student minister amid a multicultural mosaic on the raw Saskatchewan prairies just before the Great War convinced him that literature had to be a force for patriotic indoctrination and cohesion in a rapidly expanding and diverse country.

These impulses were fostered by the spiritual emphasis of his stoutly Methodist upbringing in the eastern Ontario village of Delta, and from the idealism and patriotism he drank in at Queen's University (B.A. 1912) under philosopher John Watson and theologian William Jordan. Work as a Methodist student minister amid a multicultural mosaic on the raw Saskatchewan prairies just before the Great War convinced him that literature had to be a force for patriotic indoctrination and cohesion in a rapidly expanding and diverse country.

Pierce's vision established the Ryerson Press – as the Methodist Book and Publishing House had rechristened its trade publishing section in 1919 – as a major publisher of Canadian writing, whose authors over four decades included E.J. Pratt, Harold Innis, Donald Creighton, Frederick Philip Grove, Dorothy Livesay, A.M. Klein, and F.R. Scott.

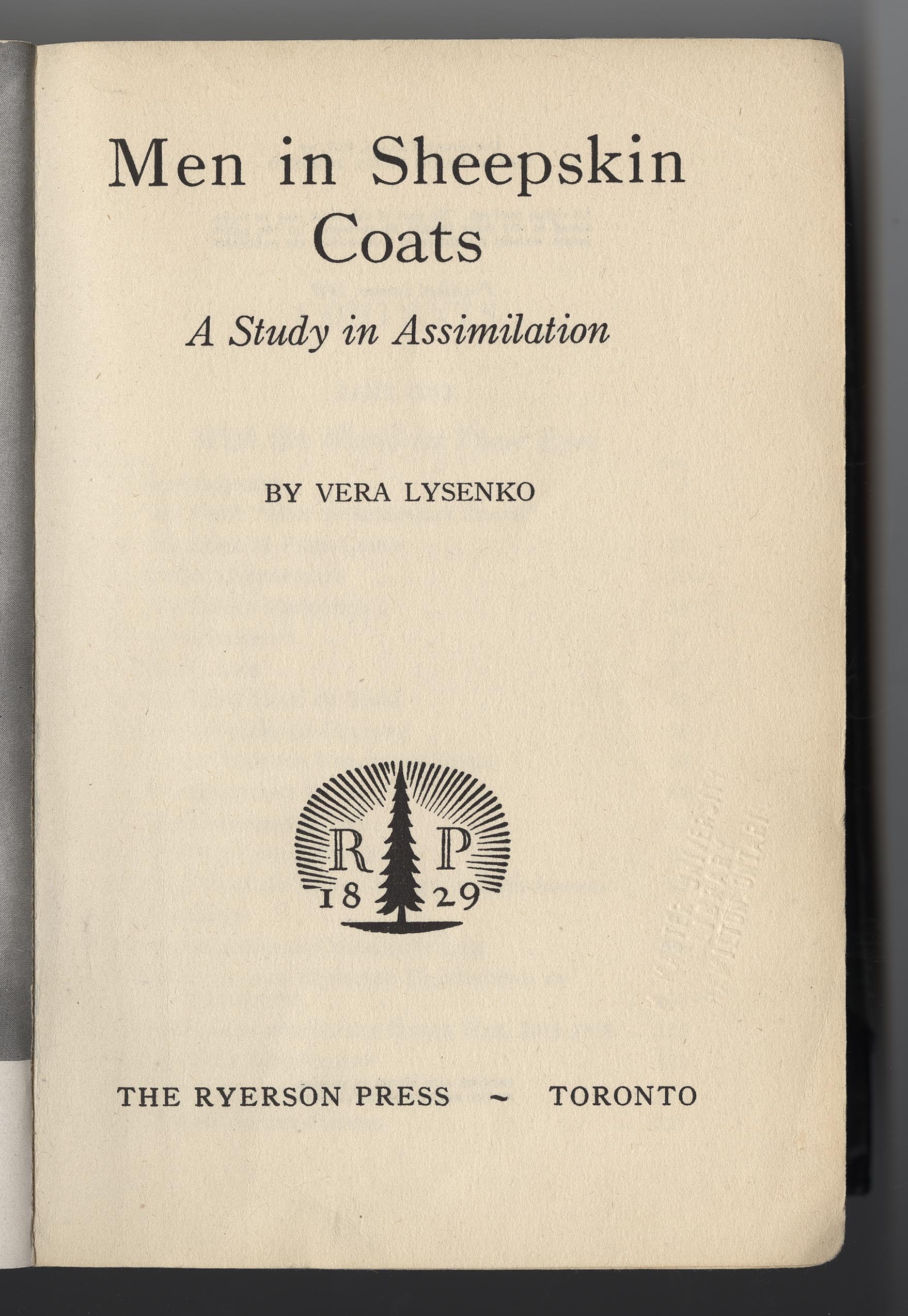

But Pierce's publishing decisions did not always go unchallenged. Vera Lysenko's Men in Sheepskin Coats: A Study In Assimilation (1947), a history of Ukrainian settlement in Canada, provides a case in point. Lysenko (1910-75), a University of Manitoba M.A. graduate who had worked as a teacher and journalist, had written precisely the kind of book that Pierce, as a Canadian nationalist, loved to publish. The work touched on Ukrainian-Canadian culture (including literature and folklore), national heroes, patterns of settlement, and the struggle for ethnic acceptance by Ukrainian Canadians as they became part of "the life of the entire Canadian nation" (205). The epigraph to Lysenko's book expressed an idea dear to Pierce's heart – that "spiritual values ... are the true measure of national greatness" (ii). Moreover, Lysenko's thesis – so close to the nationalist ideals found in Pierce's own writings, for example A Canadian People (1945) – was that Ukrainians and other immigrant groups to Canada had become not "neat little Anglo-Saxons" but rather part of a "gradual blending of varied ethnic groups into a new, totally different synthesis of all [Canadians]" (252).

But Pierce's publishing decisions did not always go unchallenged. Vera Lysenko's Men in Sheepskin Coats: A Study In Assimilation (1947), a history of Ukrainian settlement in Canada, provides a case in point. Lysenko (1910-75), a University of Manitoba M.A. graduate who had worked as a teacher and journalist, had written precisely the kind of book that Pierce, as a Canadian nationalist, loved to publish. The work touched on Ukrainian-Canadian culture (including literature and folklore), national heroes, patterns of settlement, and the struggle for ethnic acceptance by Ukrainian Canadians as they became part of "the life of the entire Canadian nation" (205). The epigraph to Lysenko's book expressed an idea dear to Pierce's heart – that "spiritual values ... are the true measure of national greatness" (ii). Moreover, Lysenko's thesis – so close to the nationalist ideals found in Pierce's own writings, for example A Canadian People (1945) – was that Ukrainians and other immigrant groups to Canada had become not "neat little Anglo-Saxons" but rather part of a "gradual blending of varied ethnic groups into a new, totally different synthesis of all [Canadians]" (252).

Nevertheless, Pierce and his author were soon attacked. By 1947, the Cold War had set in and, in North America, the chill winds of political correctness were blowing against those perceived as in any way sympathetic to Communism. The defection of Russian embassy employee Igor Gouzenko in the fall of 1945 prompted the federal Kellock-Taschereau Royal Commission, set up in February 1946, which resulted in criminal charges centred around alleged Soviet espionage in Canada and elsewhere. The net was cast wide, and some people's lives were ruined by allegations of Communist sympathies. Canada was not immune to the sort of anti-Communist witch-hunting that would soon surround the Senator Joseph McCarthy hearings in the U.S.

One leading Canadian anti-Communist crusader was McMaster English professor (and from 1948, Acadia University president) Watson Kirkconnell (1895-1977). In 1944, Kirkconnell had published Seven Pillars of Freedom, a vehement exposée of Communism in Canada, which he presented as a greater threat than Nazism. Kirkconnell was associated with a stridently anti-Communist organization, the Freedom Association of Canada (at one point he even condemned water fluoridation as a Communist plot). In the late forties, he was denouncing universities like Queen's and McGill as "hotbeds of Communism."

The multilingual Kirkconnell was known for his literary translations, which included Ukrainian-Canadian poetry. During the war, he had also published two booklets advocating Ukrainian Canadian patriotism. By 1947, Kirkconnell was closely allied with prominent anti-Communists in Ukrainian-Canadian circles, where Communism was a controversial topic, given the Ukraine's forcible absorption into the Soviet Union in 1922.

The multilingual Kirkconnell was known for his literary translations, which included Ukrainian-Canadian poetry. During the war, he had also published two booklets advocating Ukrainian Canadian patriotism. By 1947, Kirkconnell was closely allied with prominent anti-Communists in Ukrainian-Canadian circles, where Communism was a controversial topic, given the Ukraine's forcible absorption into the Soviet Union in 1922.

In such a highly-charged Cold War climate, Lysenko's book was vulnerable to attack, given that she did not roundly condemn Soviet control of the Ukraine. Nor did she detail the left-wing affiliations of some Ukrainian-Canadian organizations. Moreover, Lysenko maintained that young Ukrainian Canadians were more concerned with their Canadian lives than with politics in their ancestral homeland. She stressed to her Canadian readers that in Canada "the political interests of the Ukrainian are not different from those of any other ethnic group" (284, italics Lysenko's). Such content made Kirkconnell and his anti-Communist allies "see Red."

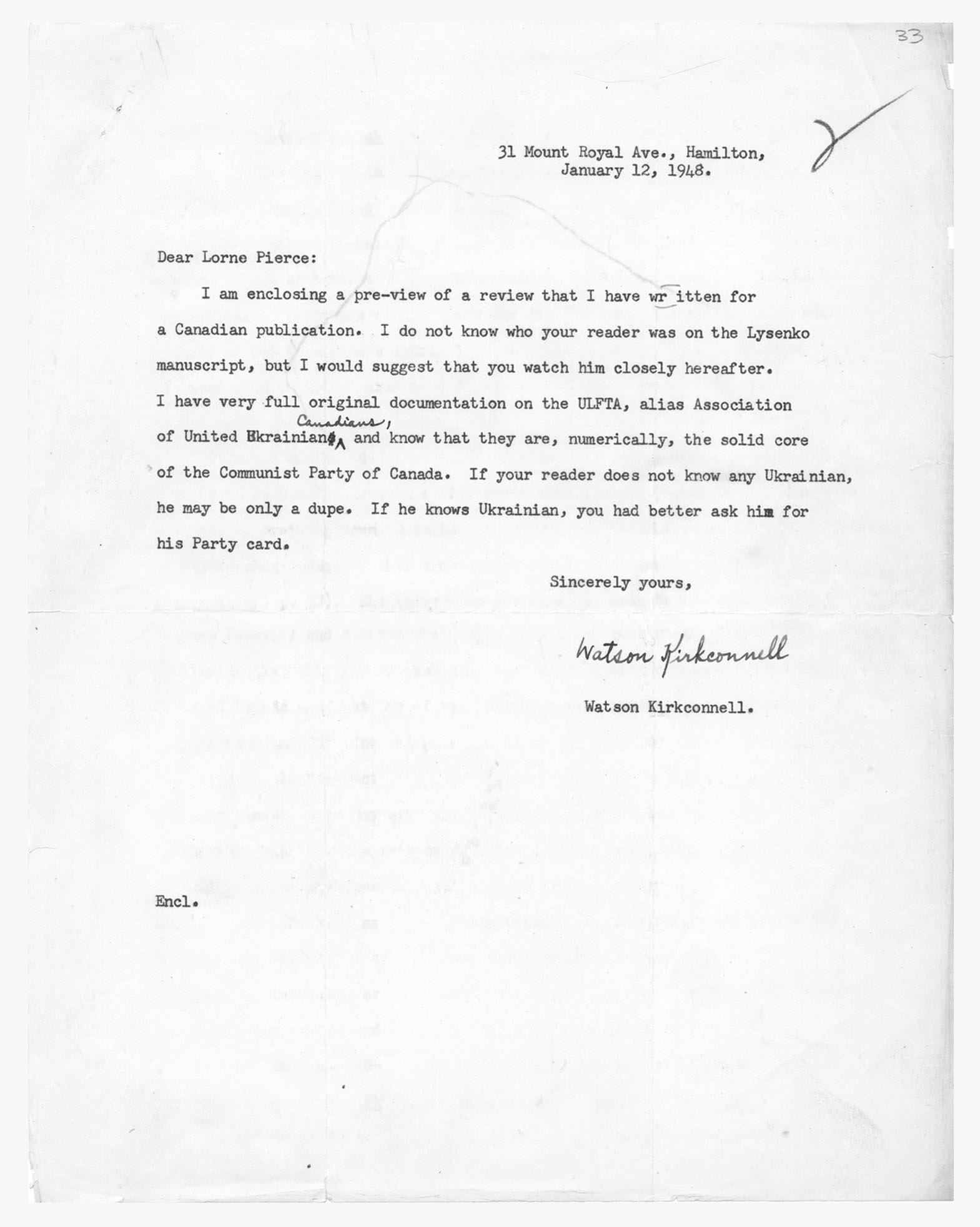

In January 1948, Kirkconnell wrote Pierce threatening to publish a damning review of the book, claiming that Lysenko had Communist affiliations and that anyone who had approved the manuscript must be either "a dupe" or a "Party card[holder]." In short, Kirkconnell insisted Ryerson was "carrying on propaganda ... for the Communist Party of Canada." That winter, three other members of the Ukrainian Canadian community also wrote to complain. One claimed that Lysenko's readership could only be "Communists, fellow travellers and deceived people."

In January 1948, Kirkconnell wrote Pierce threatening to publish a damning review of the book, claiming that Lysenko had Communist affiliations and that anyone who had approved the manuscript must be either "a dupe" or a "Party card[holder]." In short, Kirkconnell insisted Ryerson was "carrying on propaganda ... for the Communist Party of Canada." That winter, three other members of the Ukrainian Canadian community also wrote to complain. One claimed that Lysenko's readership could only be "Communists, fellow travellers and deceived people."

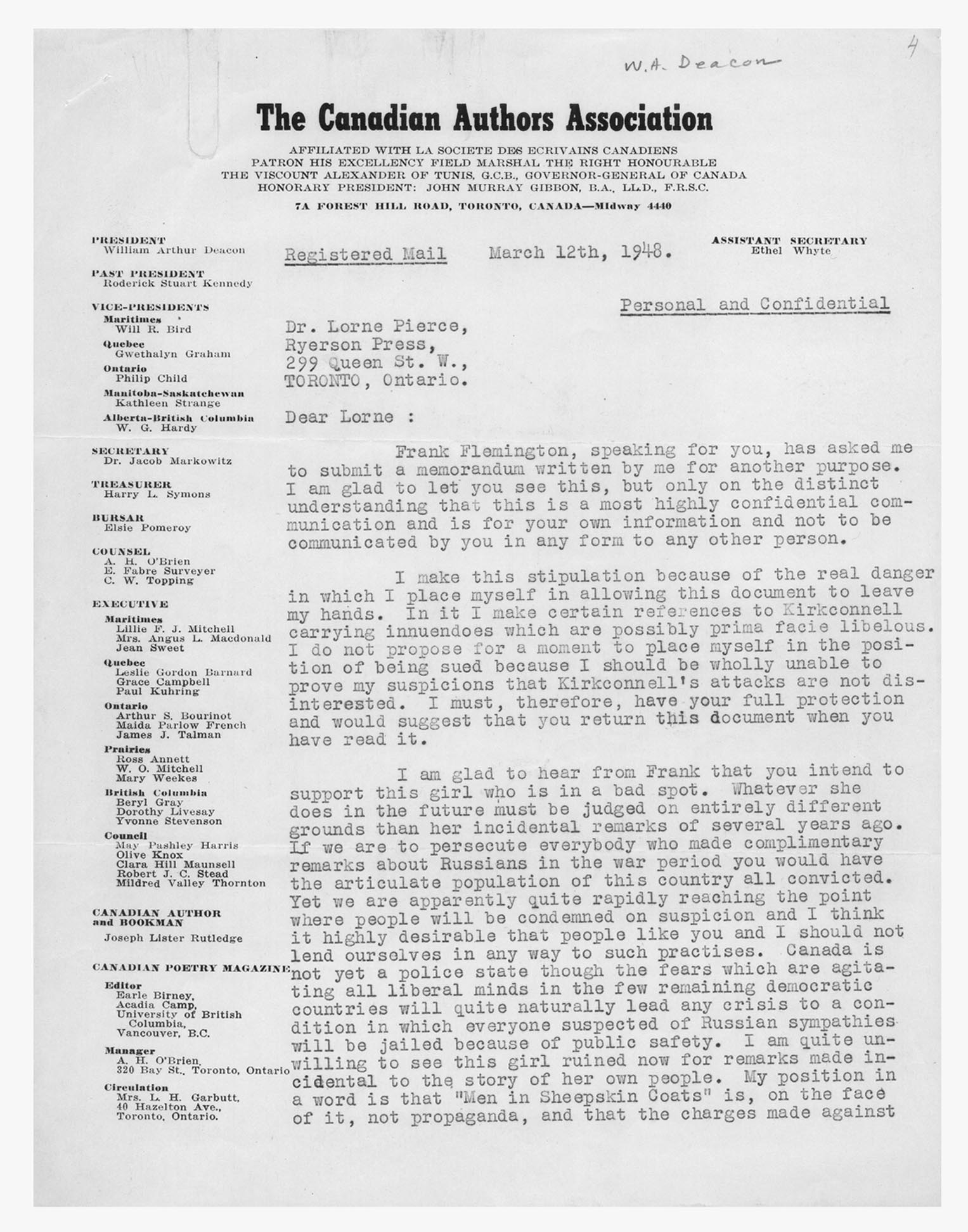

Pierce stoutly defended Lysenko, telling Kirkconnell that he believed her assertion that she was not a Communist and had done her best to be objective, adding "as  her publishers we are bound to protect her name as well as our own." Pierce enlisted the support of Globe and Mail book columnist William Arthur Deacon, then national president of the Canadian Authors Association. Deacon wrote Pierce that "I refuse to treat her as guilty because a fanatic has accused her on the basis of trivialities in the book." Pierce also persuaded prominent Canadian litterateur John Murray Gibbon to review the book positively in the March 1948 issue of the Canadian Historical Review.

her publishers we are bound to protect her name as well as our own." Pierce enlisted the support of Globe and Mail book columnist William Arthur Deacon, then national president of the Canadian Authors Association. Deacon wrote Pierce that "I refuse to treat her as guilty because a fanatic has accused her on the basis of trivialities in the book." Pierce also persuaded prominent Canadian litterateur John Murray Gibbon to review the book positively in the March 1948 issue of the Canadian Historical Review.

By mid-March, in answer to Kirkconnell's continued hectoring, Pierce even threatened legal action if Kirkconnell were to accuse in print Lysenko or Ryerson Press of Communist sympathies. In July, Kirkconnell did denounce the book in a review published in Opinion, the monthly magazine of the Ukrainian Canadian Veterans' Association, one of whose representatives had already complained to Pierce. But, despite the pressure, Pierce did not withdraw the book, or forsake Lysenko.

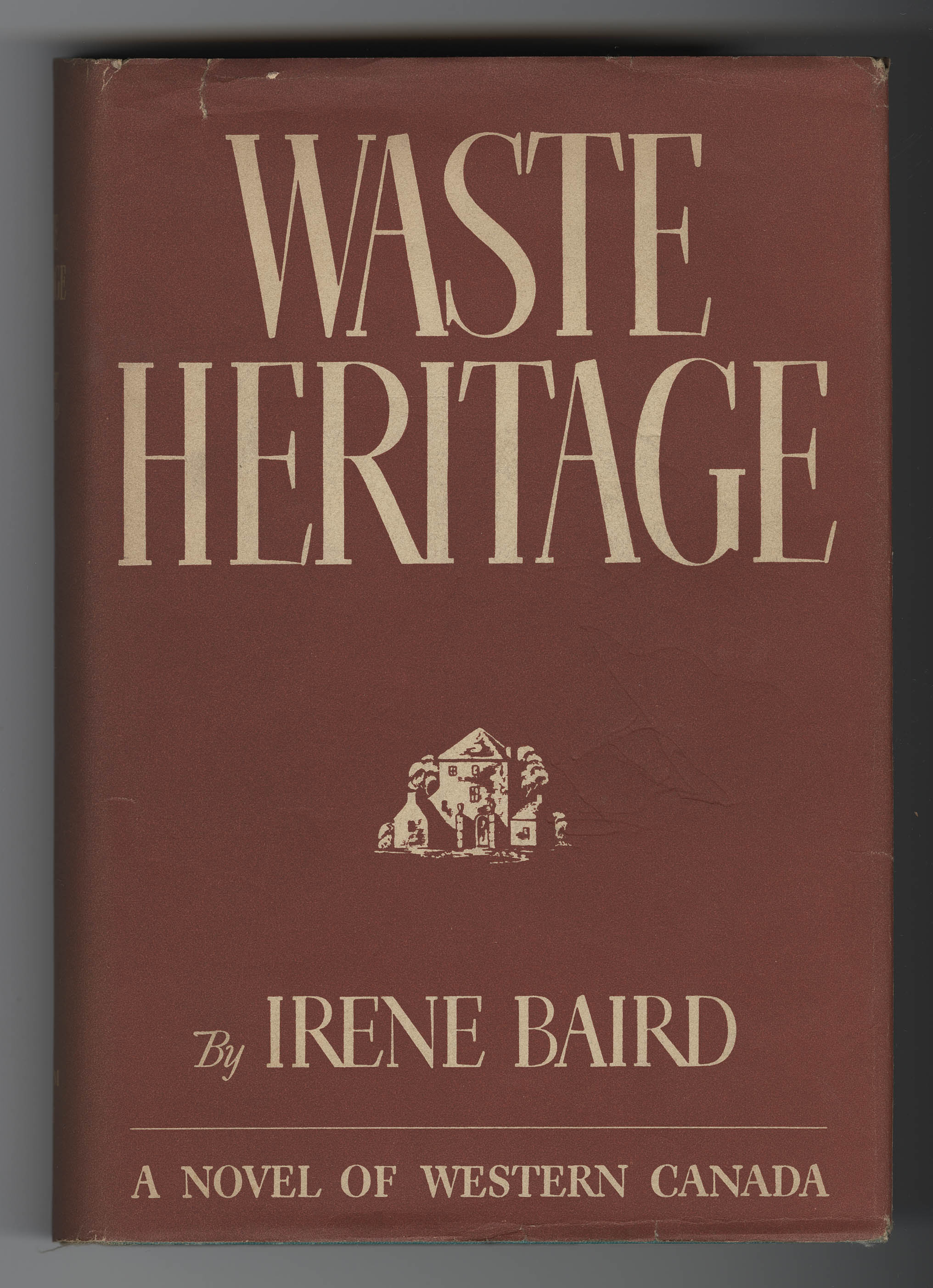

Pierce showed courage. Jody Mason has chronicled the uneasiness of another Canadian publisher, Hugh Earys at Macmillan of Canada, about the "redness" of Irene Baird's Depression novel Waste Heritage (1939), with Macmillan requiring some manuscript changes in light of the Defence of Canada Act. More broadly, other Canadians accused – in the press and/or in the courts – of Communist sympathies, had been shunned by associates after being smeared. For example, federal government economist Agatha Chapman lost her civil service job, even after espionage charges against her were thrown out of court in 1946. By contrast, Pierce went on to publish two novels by Lysenko: Yellow Boots (1954), the coming-of-age story of a young Ukrainian-Canadian girl, and Westerly Wild (1956), a Depression novel of Saskatchewan. Pierce published these novels despite another attack in 1953 on Lysenko's history as "subtle communist propaganda" in Paul Yuzyk's The Ukrainians in Manitoba, more evidence of the fact that the charge would cling to Lysenko's literary reputation for years. But Pierce stood behind his author. His dealings with authors like Pratt and Louis Dudek show that he could be prudish about the treatment of sex and alcohol in Ryerson publications. But, as he assured Dorothy Livesay in 1949 when she worried about public criticism of her work due to past Communist affiliations: "You must know by this time that I do not go around taking a poll of opinion and that if there is any degradation of opinion in Canada I have never contributed to it in that way. We have allowed our authors to say what they think ..." The archival record reveals Pierce’s grit during an era of moral panic about Communism.

Pierce showed courage. Jody Mason has chronicled the uneasiness of another Canadian publisher, Hugh Earys at Macmillan of Canada, about the "redness" of Irene Baird's Depression novel Waste Heritage (1939), with Macmillan requiring some manuscript changes in light of the Defence of Canada Act. More broadly, other Canadians accused – in the press and/or in the courts – of Communist sympathies, had been shunned by associates after being smeared. For example, federal government economist Agatha Chapman lost her civil service job, even after espionage charges against her were thrown out of court in 1946. By contrast, Pierce went on to publish two novels by Lysenko: Yellow Boots (1954), the coming-of-age story of a young Ukrainian-Canadian girl, and Westerly Wild (1956), a Depression novel of Saskatchewan. Pierce published these novels despite another attack in 1953 on Lysenko's history as "subtle communist propaganda" in Paul Yuzyk's The Ukrainians in Manitoba, more evidence of the fact that the charge would cling to Lysenko's literary reputation for years. But Pierce stood behind his author. His dealings with authors like Pratt and Louis Dudek show that he could be prudish about the treatment of sex and alcohol in Ryerson publications. But, as he assured Dorothy Livesay in 1949 when she worried about public criticism of her work due to past Communist affiliations: "You must know by this time that I do not go around taking a poll of opinion and that if there is any degradation of opinion in Canada I have never contributed to it in that way. We have allowed our authors to say what they think ..." The archival record reveals Pierce’s grit during an era of moral panic about Communism.

Campbell, Sandra. "Nationalism, Morality and Gender: Lorne Pierce and the Canadian Literary Canon, 1920-1960." Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 32:2 (Fall 1994): 135-60.

Friskney, Janet B. "From Methodist Literary Culture to Canadian Literary Culture: The United Church Publishing House/The Ryerson Press, 1829-1970." In Literary Cultures and the Material Book, ed. Simon Eliot, Andrew Nash, and Ian Willison, 379-85. London: The British Library, 2007.

Gibbon, John Murray. Review of Men in Sheepskin Coats, Canadian Historical Review 29:1 (March 1948): 88.

Gibson, Frederick W. Queen's University Volume II 1917-1961: To Serve and Yet Be Free. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1983.

Kirkconnell, Watson. Our Ukrainian Loyalists (Ukrainian Canadian Committee). Winnipeg: Ukrainian Canadian Committee, 1943.

—. Seven Pillars of Freedom. Toronto: Oxford, 1944; revised edition, Toronto: Burns and MacEachern, 1952.

—. A Slice of Canada. Toronto: Toronto University Press for Acadia University, 1967.

—. The Ukrainian Canadians and the War. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1940.

Lysenko, Vera. Men in Sheepskin Coats: A Study in Assimilation. Toronto: Ryerson, 1947.

McDowall, Duncan. "The Trial and Tribulations of Miss Agatha Chapman: Statistics in a Cold War Climate." Queen's Quarterly 114:3 (Fall 2007): 357-73.

Mason, Jody. "‘Sidown, Brother, Sidown!’: The Problem of Commitment and the Publishing History of Irene Baird's Waste Heritage." Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada 45:2 (Fall 2007): 143-61.

Pierce, Lorne. A Canadian People. Toronto: Ryerson, 1945.

Yuzyk, Paul. The Ukrainians in Manitoba: A Social History. Toronto: Toronto University Press for the Historical and Scientific Society of Manitoba, 1953.

Lorne and Edith Pierce collection, Queen's University Archives