The Publication of Alistair MacLeod's The Lost Salt Gift of Blood

Rick Stapleton, McMaster University

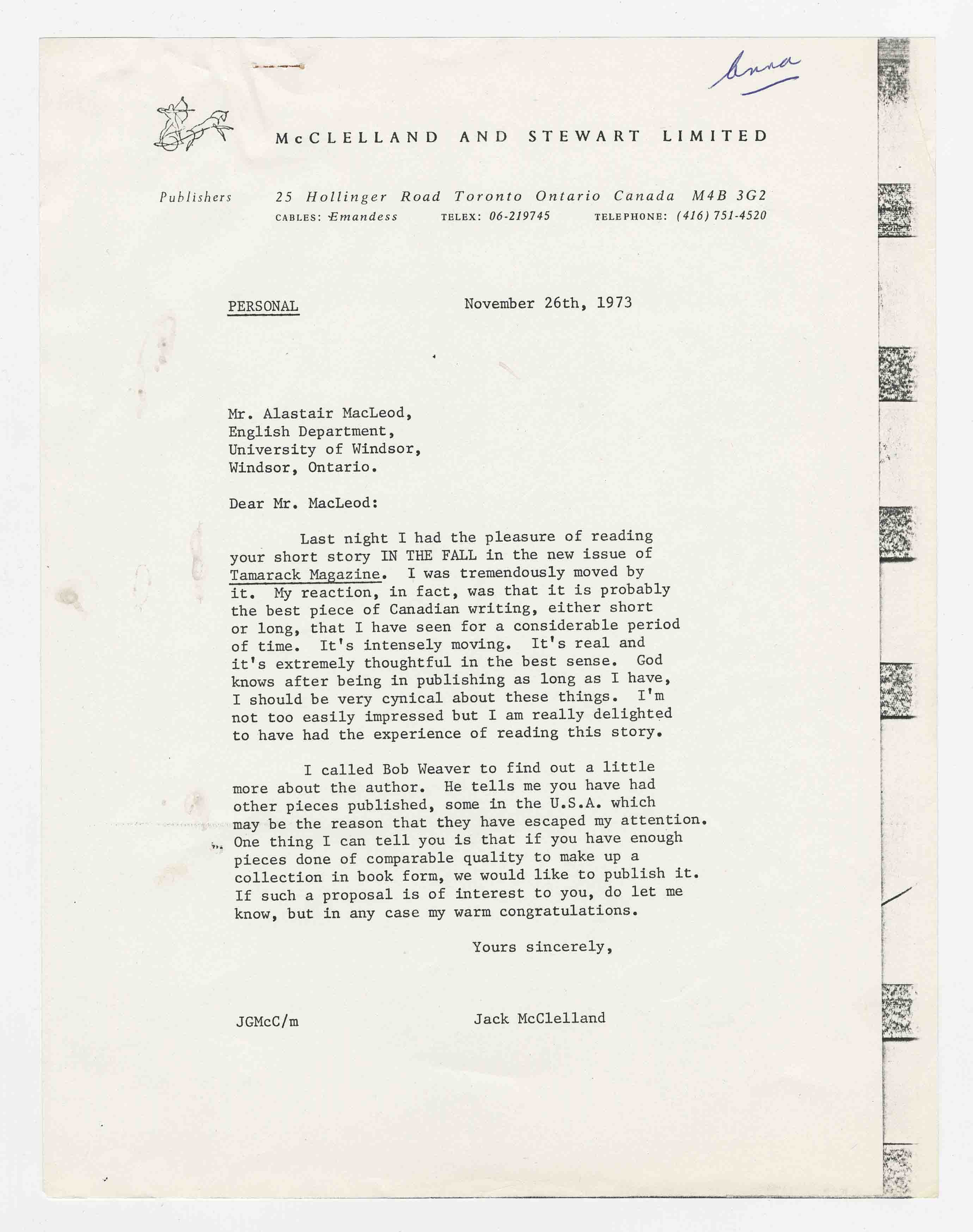

On the night of 25 November 1973, Jack McClelland read Alistair MacLeod’s short story “In the Fall” which had just been published in Tamarack Review. He was so impressed that he wrote to MacLeod at the University of Windsor the very next day to tell him: “God knows after being in publishing as long as I have, I should be very cynical about these things. I’m not too easily impressed but I am really delighted to have had the experience of reading this story ... One thing I can tell you is that if you have enough pieces done of comparable quality to make  up a collection in book form, we would like to publish it.” In his prompt reply on 3 December, MacLeod stated “I am quite interested in your suggestion concerning a possible collection,” and sent along copies of three stories, “The Boat,” “The Return,” and “The Lost Salt Gift of Blood.” McClelland handed the manuscripts over to senior editor Lily Miller for comment. After reviewing them in a little over a week, Miller conceded that MacLeod was a “fine writer” but she had reservations about the possibility of publishing a collection of his stories—MacLeod “seems always to deal with the same locale and people ... This makes me wonder how varied a collection we could have ... There are really only two strong stories here, and even they tend to overlap in subject matter.” She was particularly critical of “The Return”—“there is an artificiality to the handling” and “were we to do a collection of Alistair MacLeod’s work, I would not recommend inclusion of this piece.”

up a collection in book form, we would like to publish it.” In his prompt reply on 3 December, MacLeod stated “I am quite interested in your suggestion concerning a possible collection,” and sent along copies of three stories, “The Boat,” “The Return,” and “The Lost Salt Gift of Blood.” McClelland handed the manuscripts over to senior editor Lily Miller for comment. After reviewing them in a little over a week, Miller conceded that MacLeod was a “fine writer” but she had reservations about the possibility of publishing a collection of his stories—MacLeod “seems always to deal with the same locale and people ... This makes me wonder how varied a collection we could have ... There are really only two strong stories here, and even they tend to overlap in subject matter.” She was particularly critical of “The Return”—“there is an artificiality to the handling” and “were we to do a collection of Alistair MacLeod’s work, I would not recommend inclusion of this piece.”

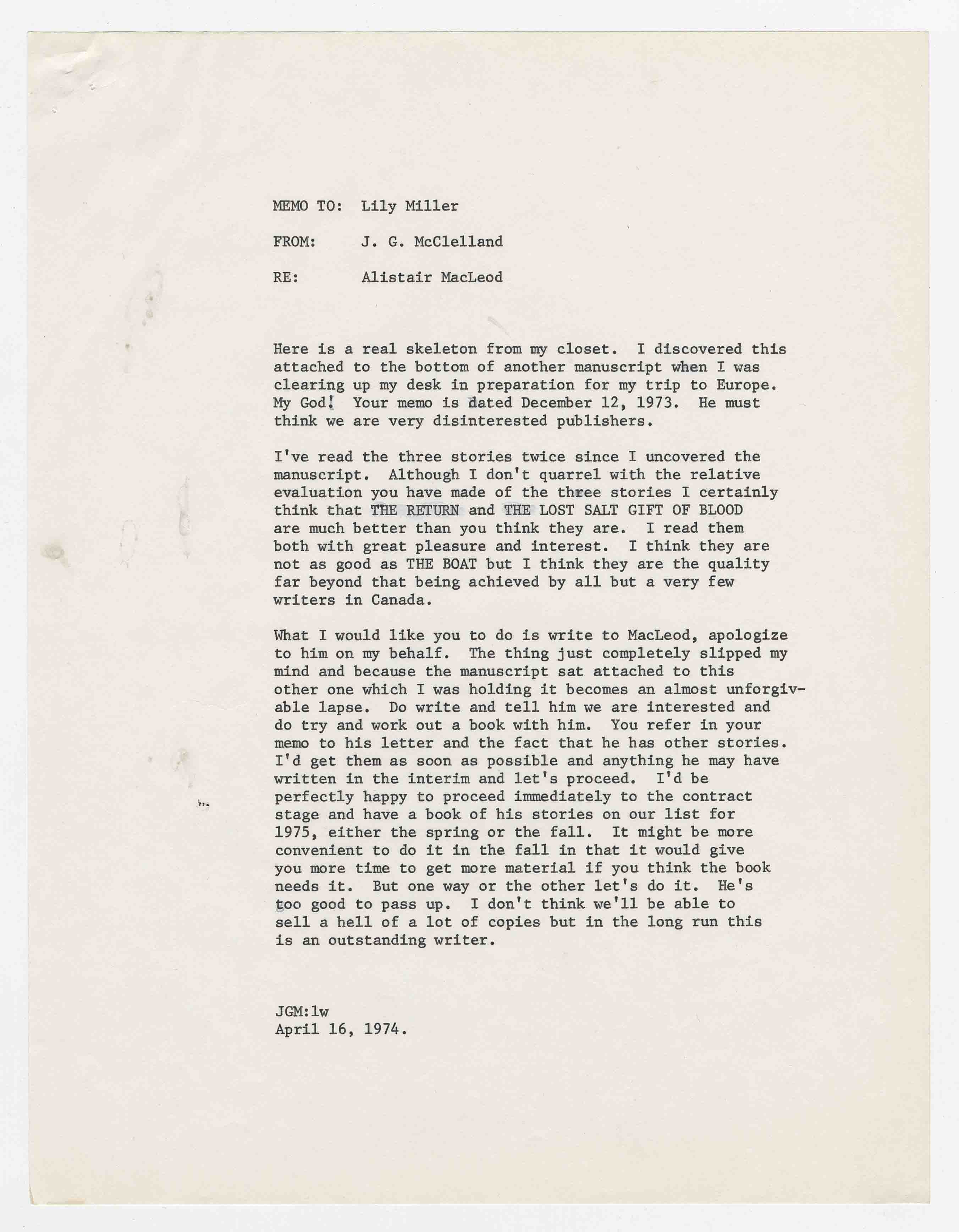

Only three weeks had passed since McClelland’s initial reading of the story, his exchange of letters with MacLeod, and Miller’s evaluation of the manuscripts, and  then, silence —for four months! The delay was caused by an unfortunate oversight on McClelland’s part. “Here is a real skeleton in my closet,” he wrote to Miller in April of 1974. “I discovered this [MacLeod’s manuscripts] attached to the bottom of another manuscript when I was clearing up my desk in preparation for my trip to Europe. My God! ... He must think we are disinterested publishers.” He instructed Miller to contact MacLeod immediately with an apology and to “try to work out a book with him.” In addressing Miller’s reservations about the stories, McClelland stated that he thought they were “much better than you think they are” and were of a “quality far beyond that being achieved by all but a few writers in Canada.”

then, silence —for four months! The delay was caused by an unfortunate oversight on McClelland’s part. “Here is a real skeleton in my closet,” he wrote to Miller in April of 1974. “I discovered this [MacLeod’s manuscripts] attached to the bottom of another manuscript when I was clearing up my desk in preparation for my trip to Europe. My God! ... He must think we are disinterested publishers.” He instructed Miller to contact MacLeod immediately with an apology and to “try to work out a book with him.” In addressing Miller’s reservations about the stories, McClelland stated that he thought they were “much better than you think they are” and were of a “quality far beyond that being achieved by all but a few writers in Canada.”

Miller did as she was instructed and contacted MacLeod. In his reply, the author  commented dryly: “Things do get mislaid.” He also included “a few other stories for your perusal.” But he was not yet ready to make a firm commitment to M&S: “Everyone seems to consider me a very hot property at the present time, or at least a warm one with hot potentialities. I say this merely because I would like to see my way as clearly as possible before formally agreeing to any publishing venture.” Given MacLeod’s hesitation, McClelland acted swiftly and arranged a meeting with the writer to attempt to persuade him to publish with M&S. Upon receiving assurances that the book would be of good quality in hardcover, MacLeod agreed to a deal. Miller was to be the editor.

commented dryly: “Things do get mislaid.” He also included “a few other stories for your perusal.” But he was not yet ready to make a firm commitment to M&S: “Everyone seems to consider me a very hot property at the present time, or at least a warm one with hot potentialities. I say this merely because I would like to see my way as clearly as possible before formally agreeing to any publishing venture.” Given MacLeod’s hesitation, McClelland acted swiftly and arranged a meeting with the writer to attempt to persuade him to publish with M&S. Upon receiving assurances that the book would be of good quality in hardcover, MacLeod agreed to a deal. Miller was to be the editor.

Over the next several months, MacLeod and Miller developed a frank and honest relationship, enhanced with warmth and humour, to an extent that Miller became one of MacLeod’s greatest admirers and defenders. Miller candidly expressed her concerns with the story “The Return,” stating: “Frankly, I would be happier to leave it out. What do you think?” MacLeod agreed that Miller’s assessment was “fairly accurate.” However, he thought that it would be unfortunate to omit it because the story was already well known from having been broadcast on the radio by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and because they were already looking at a fairly slim volume: “It would be nice to somehow stagger to 100 pages” (14 June 1974).The story stayed in the collection.

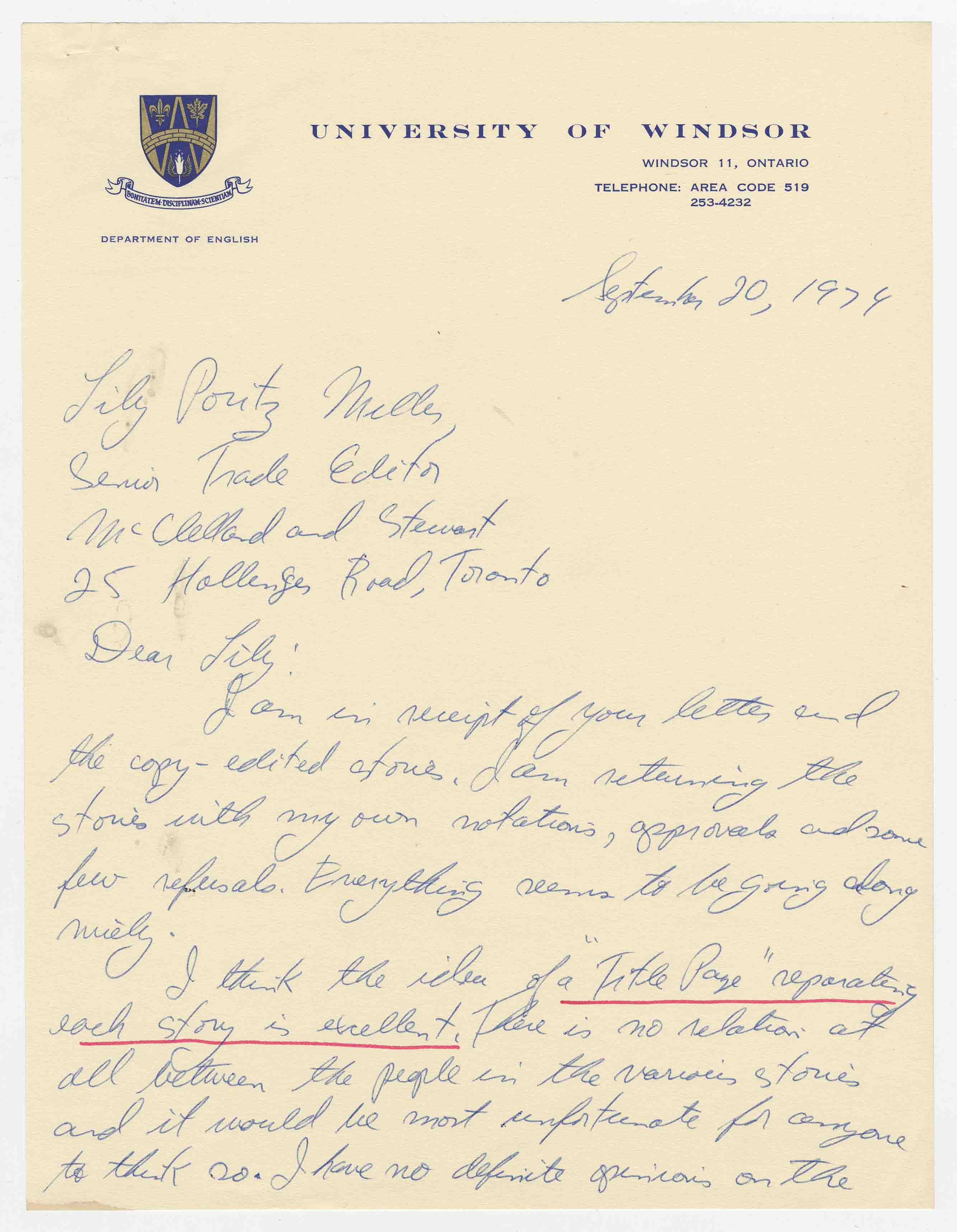

In reply to Miller’s assessment that the stories “deal with the same locale and  people,” MacLeod stated: “There is no relation at all between the people in the various stories and it would be most unfortunate for anyone to think so.” Miller’s simple solution to the potential confusion was to separate each story with a title page, an idea MacLeod thought “was excellent.” The last issue to be worked out between Miller and MacLeod was that of the collection’s title. “I realize,” wrote MacLeod, “The Lost Salt Gift of Blood is awkward but I also think it is ... indicative of all the stories. Each story deals with various tensions that exist between or among those of similar blood or relationships.” He acknowledged that while a title such as “The Lost Deflowered Virgin might help a book’s sales, there were other considerations as well." The title was not changed.

people,” MacLeod stated: “There is no relation at all between the people in the various stories and it would be most unfortunate for anyone to think so.” Miller’s simple solution to the potential confusion was to separate each story with a title page, an idea MacLeod thought “was excellent.” The last issue to be worked out between Miller and MacLeod was that of the collection’s title. “I realize,” wrote MacLeod, “The Lost Salt Gift of Blood is awkward but I also think it is ... indicative of all the stories. Each story deals with various tensions that exist between or among those of similar blood or relationships.” He acknowledged that while a title such as “The Lost Deflowered Virgin might help a book’s sales, there were other considerations as well." The title was not changed.

There was one final hurdle to overcome before the book was published. As the production date drew near, Anna Porter, editorial director at M&S, sent a memo to Miller suggesting that the collection be produced in paperback instead of hardcover. MacLeod was not at all pleased with this turn of events, and Miller defended him, telling Porter that “quality treatment” was MacLeod’s “prime concern and it was promised to him before he signed the contract.” She added: “MacLeod is a serious writer of great promise and I think it is important for us to keep him happy if it is within our power.” Porter agreed, and The Lost Salt Gift of Blood was published in hardcover in January 1976.

In their last exchange of letters, MacLeod and Miller expressed their mutual admiration. “I would like to say once more,” wrote MacLeod, “how much I appreciate your work on my book. It’s not often that one gets so much of what one wants in such an endeavour.” Miller replied on 11 November 1976: “Thank you for your beautiful letter. I was about to write and express similar feelings. All along I have had a very special affection for your book and now I feel the same way about you. Relationships of this sort really make everything worthwhile.” From her early hesitation over some of the stories, Miller had come to greatly appreciate MacLeod as a writer and as a person.

The book itself received great critical acclaim. In a letter to McClelland, Hugh MacLennan enthused on 26 March 1976: “With The Lost Salt Gift of Blood, you may well have published the finest book ever written in this country.” A happy ending for a book that, because of a senior editor’s initial lack of enthusiasm and mislaid manuscripts, might never have been published by M&S.

Berces, Francis. “Existential Maritimer: Alistair Macleod's The Lost Salt Gift of Blood.” Studies in Canadian Literature. 16.1 (1991).

http://www.lib.unb.ca/Texts/SCL/bin/get.cgi?directory=vol16_1/&filename…

Boyd, Colin. “Alistair MacLeod.” Canadian Encyclopedia.

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA…

Guilford, Irene, ed. Alistair MacLeod: essays on his work. Toronto: Guernica Editions, 2001.

http://www.guernicaeditions.com/title.php?id=9781550711370

McClelland & Stewart Ltd. fonds, McMaster University