William Arthur Deacon: Reviewing, Advertising, and Publishers

John Lennox, York University

Deacon’s reviews consistently reached the largest newspaper readership in Canada and for this reason, publishers were ready to place advertisements for their authors in his book pages. Throughout Deacon’s years as literary editor, the correlation linking advertising, the sale of books, and his reviews was a consistent aspect of his career, his influence, and his employment. Canada’s market was relatively small, his book pages were the

Deacon’s reviews consistently reached the largest newspaper readership in Canada and for this reason, publishers were ready to place advertisements for their authors in his book pages. Throughout Deacon’s years as literary editor, the correlation linking advertising, the sale of books, and his reviews was a consistent aspect of his career, his influence, and his employment. Canada’s market was relatively small, his book pages were the  most widely read, and publishers needed to reach those who read Deacon’s column. His notice and reviews of their books were crucial to sales.

most widely read, and publishers needed to reach those who read Deacon’s column. His notice and reviews of their books were crucial to sales.

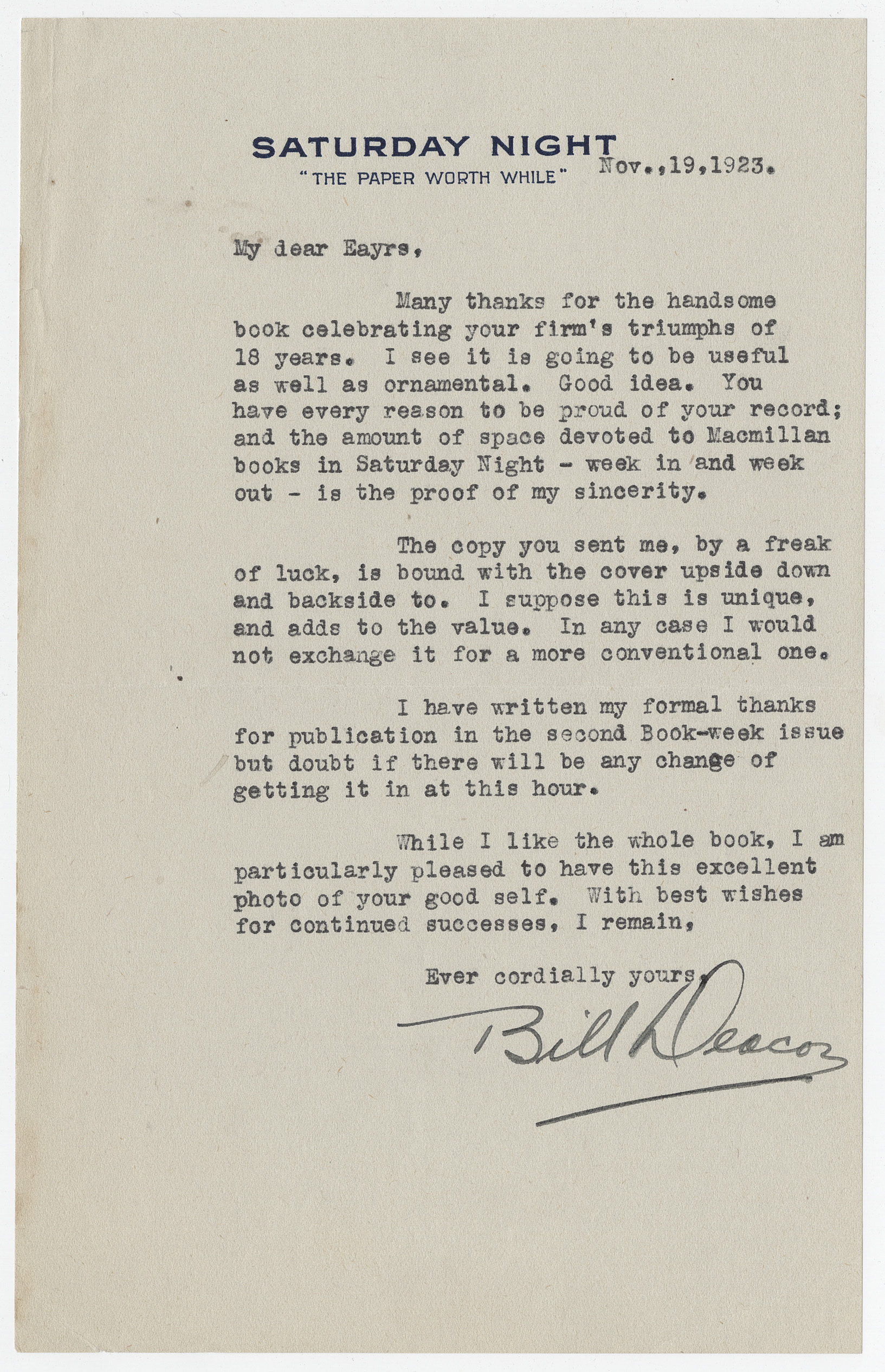

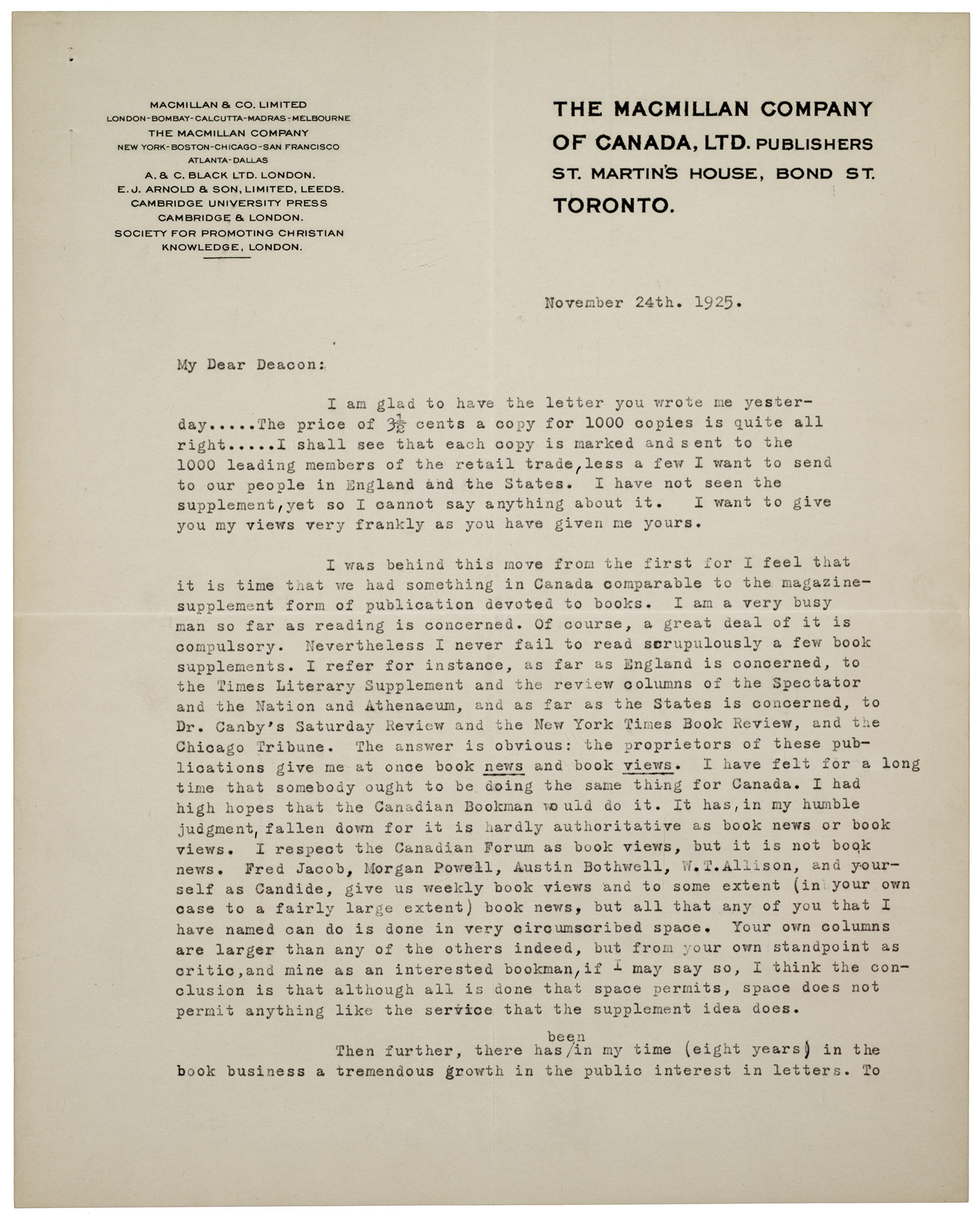

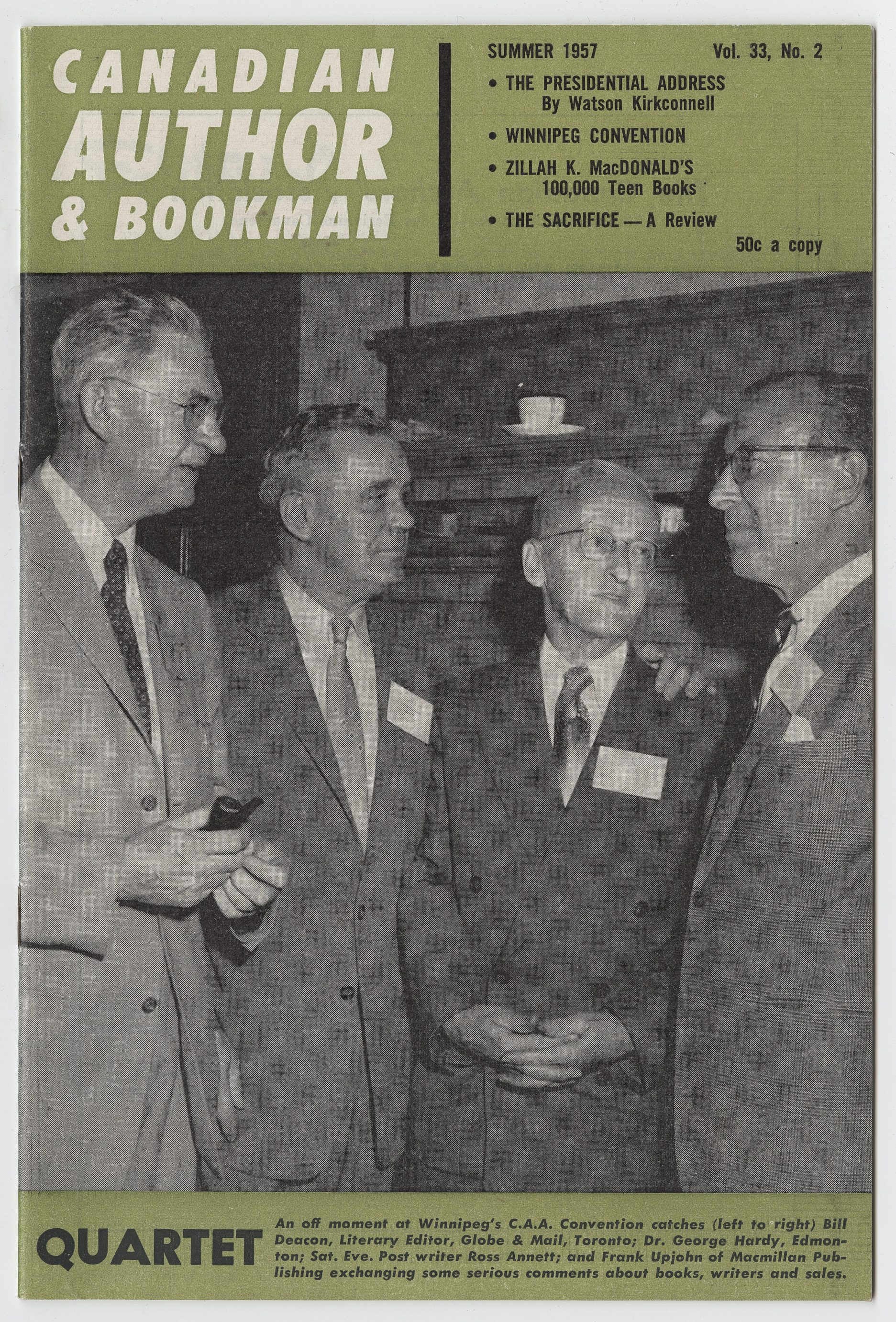

Although soliciting advertising revenues was part of his job, in the 1920s and 1930s Deacon was particularly implicated in this aspect of his work. During one two-year period at Saturday Night, he doubled the number of publishers’ advertisements from 26 to 52. In 1931, as the Great Depression worsened, Deacon was told by the Mail and Empire that if he could generate half his salary from advertising revenues, the book page would be retained. In the end, he was able to finance his entire salary through revenues from advertising. When he became literary editor of the Globe and Mail in 1936, advertising immediately rose from 11,000 to 40,000  lines. Though these revenues remained important, the pressure on Deacon to secure them himself appears to have lessened in the 1940s and 1950s.

lines. Though these revenues remained important, the pressure on Deacon to secure them himself appears to have lessened in the 1940s and 1950s.

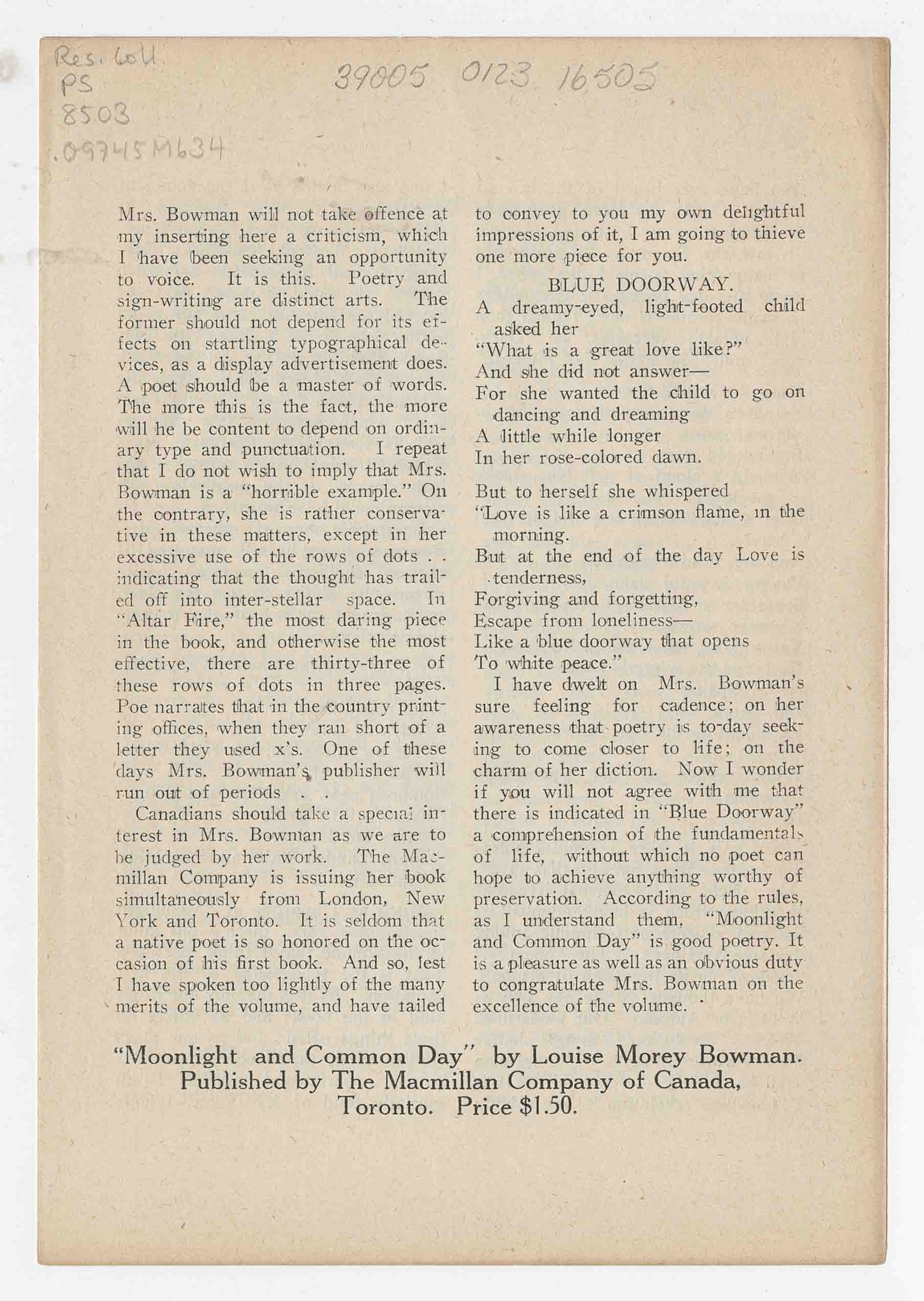

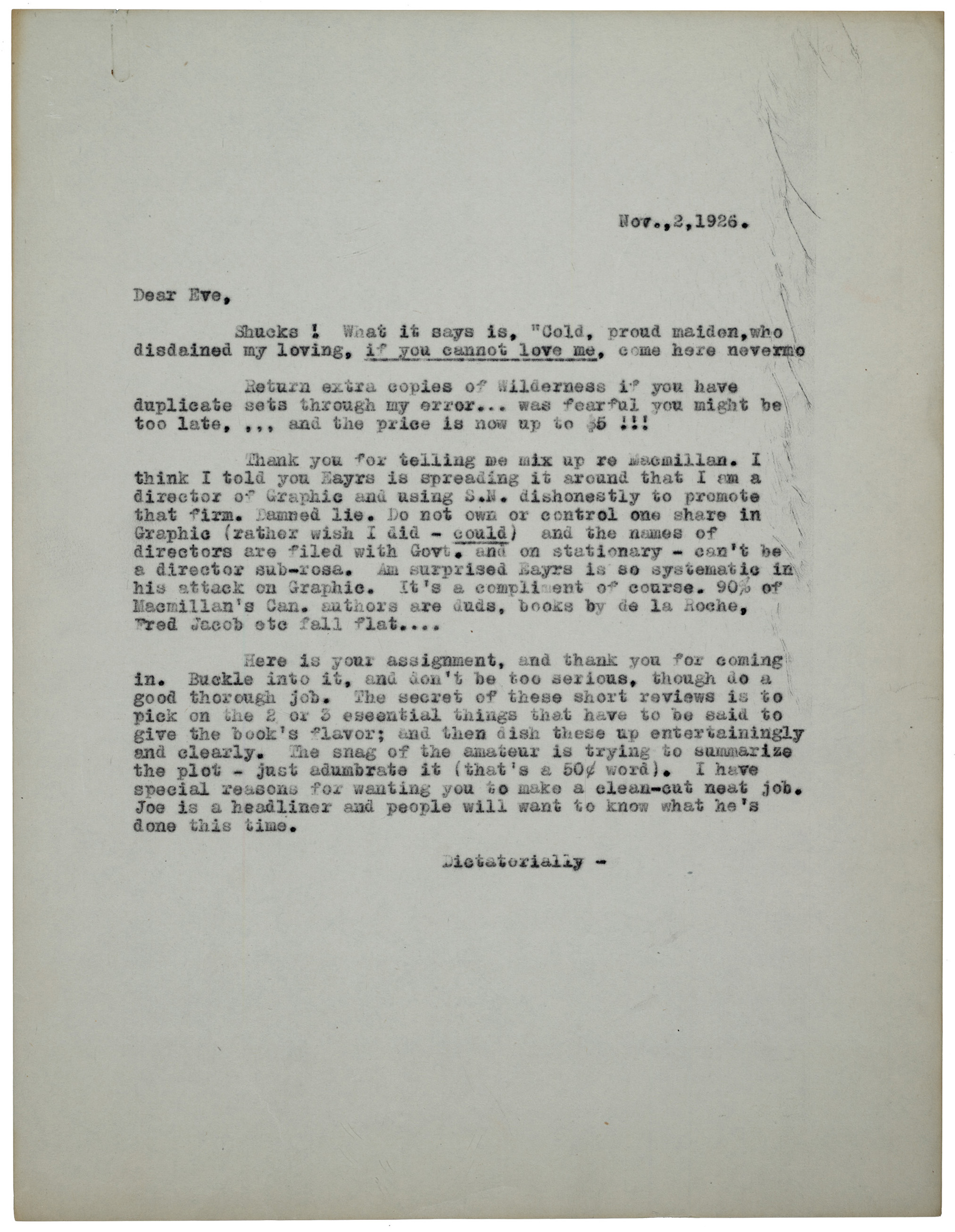

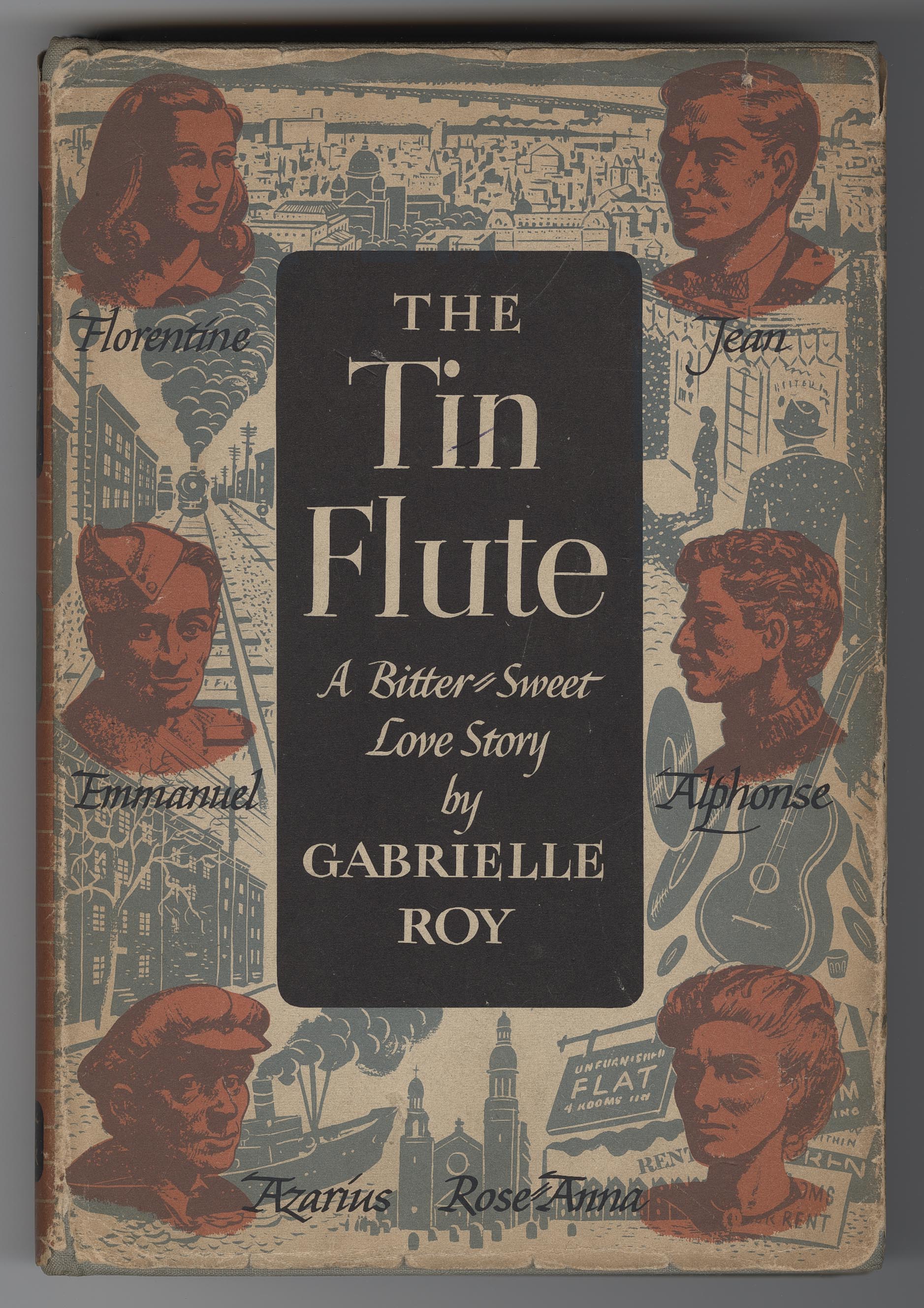

Advertising by bigger publishing houses like Macmillan of Canada, Nelson, Doubleday, and McClelland & Stewart was critical to the financial health of the book page, and publishers could be annoyed by any perceived preference. In the 1920s, Deacon’s cultural nationalism created an enthusiasm for Graphic Publishers of Ottawa, that was wrongly blamed as favouritism for that publisher over others. Hugh Eayrs of Macmillan of Canada had a prickly sense  of his firm’s precedence which prompted him in 1926 and 1927 to withdraw advertising from the book pages as a protest against ads for the recently established book club, The Literary Guild. Eayrs saw the club as a threat to Macmillan’s sales. Twenty years later, the same club participated in the unprecedented success of Gabrielle Roy’s The Tin Flute, by naming it the Guild’s choice of the month. These were the vicissitudes of a small literary community. While there were differences and bruised egos from time to time, publishers and critics made common cause in the promotion of Canadian writers and Canadian books.

of his firm’s precedence which prompted him in 1926 and 1927 to withdraw advertising from the book pages as a protest against ads for the recently established book club, The Literary Guild. Eayrs saw the club as a threat to Macmillan’s sales. Twenty years later, the same club participated in the unprecedented success of Gabrielle Roy’s The Tin Flute, by naming it the Guild’s choice of the month. These were the vicissitudes of a small literary community. While there were differences and bruised egos from time to time, publishers and critics made common cause in the promotion of Canadian writers and Canadian books.

The holiday season was an important occasion for the purchase of books, and Deacon’s annual “Christmas Review of Books” in the Globe and Mail filled two or three pages in early December. One of its features was a list of books recommended as gifts. Not surprisingly, publishers’ advertisements in this section occupied one-third to one-half of the Christmas pages; some firms even paid a bonus for a particular position on the page.

Deacon was not afraid to dismiss a bad book, but his tendency was to review positively. In fact, Deacon was anxious for the publishers’ success because such success indicated that Canadian books were being bought and read. In  the 1940s and 1950s, for example, his laudatory reviews of writers like Hugh MacLennan and Thomas Costain had a significant impact on sales. Deacon was also innovative in aggressively introducing and promoting the work of French-Canadian writers. In 1945 he wrote very favourably about Gabrielle Roy’s Bonheur d’occasion, and again at the time of its publication in English translation by McClelland & Stewart in 1947 as The Tin Flute. He was enthusiastic about Roger Lemelin and Germaine Guèvremont. His active promotion of the vision of a bicultural national literature resonated with his readers and their book-buying practices. Roy, for example, was Deacon’s particular favourite, and her book tour,

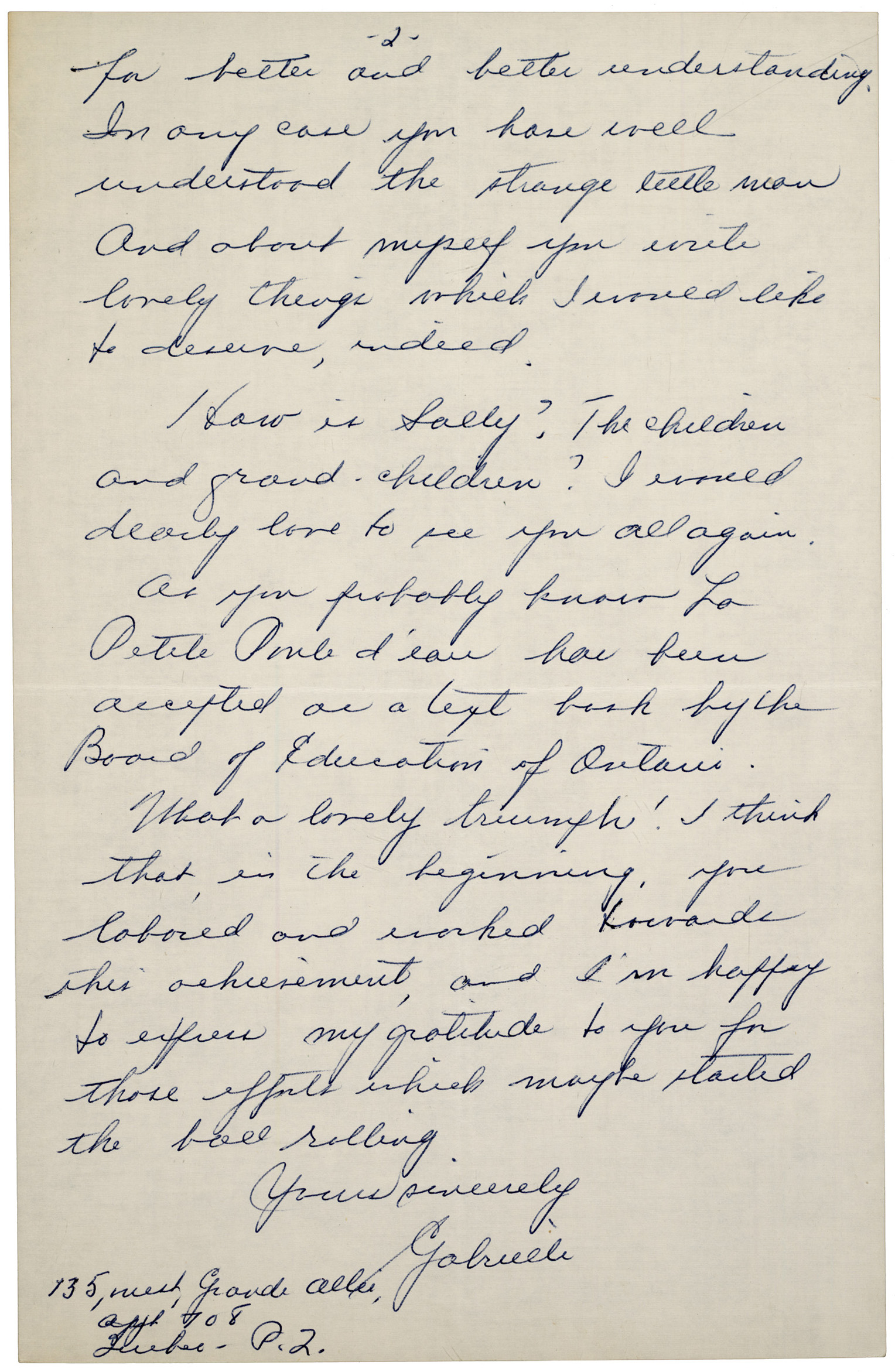

the 1940s and 1950s, for example, his laudatory reviews of writers like Hugh MacLennan and Thomas Costain had a significant impact on sales. Deacon was also innovative in aggressively introducing and promoting the work of French-Canadian writers. In 1945 he wrote very favourably about Gabrielle Roy’s Bonheur d’occasion, and again at the time of its publication in English translation by McClelland & Stewart in 1947 as The Tin Flute. He was enthusiastic about Roger Lemelin and Germaine Guèvremont. His active promotion of the vision of a bicultural national literature resonated with his readers and their book-buying practices. Roy, for example, was Deacon’s particular favourite, and her book tour,  coupled with Deacon’s reviews and comments and the advertising in his book pages, ensured unprecedented sales of The Tin Flute in English Canada. And Roy ascribed to him the Ontario Department of Education’s adoption in 1955 of La petite poule d’eau as a text for high school French courses.

coupled with Deacon’s reviews and comments and the advertising in his book pages, ensured unprecedented sales of The Tin Flute in English Canada. And Roy ascribed to him the Ontario Department of Education’s adoption in 1955 of La petite poule d’eau as a text for high school French courses.

At the end of his career, Deacon said that he had staked his life on Canadian literature and had won. He would have been the first to admit the interdependence of writer, publisher, and critic that had made such success possible.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd. fonds, McMaster University

Macmillan Company of Canada fonds, McMaster University

William Arthur Deacon [collection], Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto

!["Billy" Sunday : the man and his message, [1915]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000005.jpg?itok=5-pxPBhG)

!["Billy" Sunday : the man and his message, [1915]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000005-2.jpg?itok=ENb7n96W)