Censorship in Canada

Pearce J. Carefoote, University of Toronto

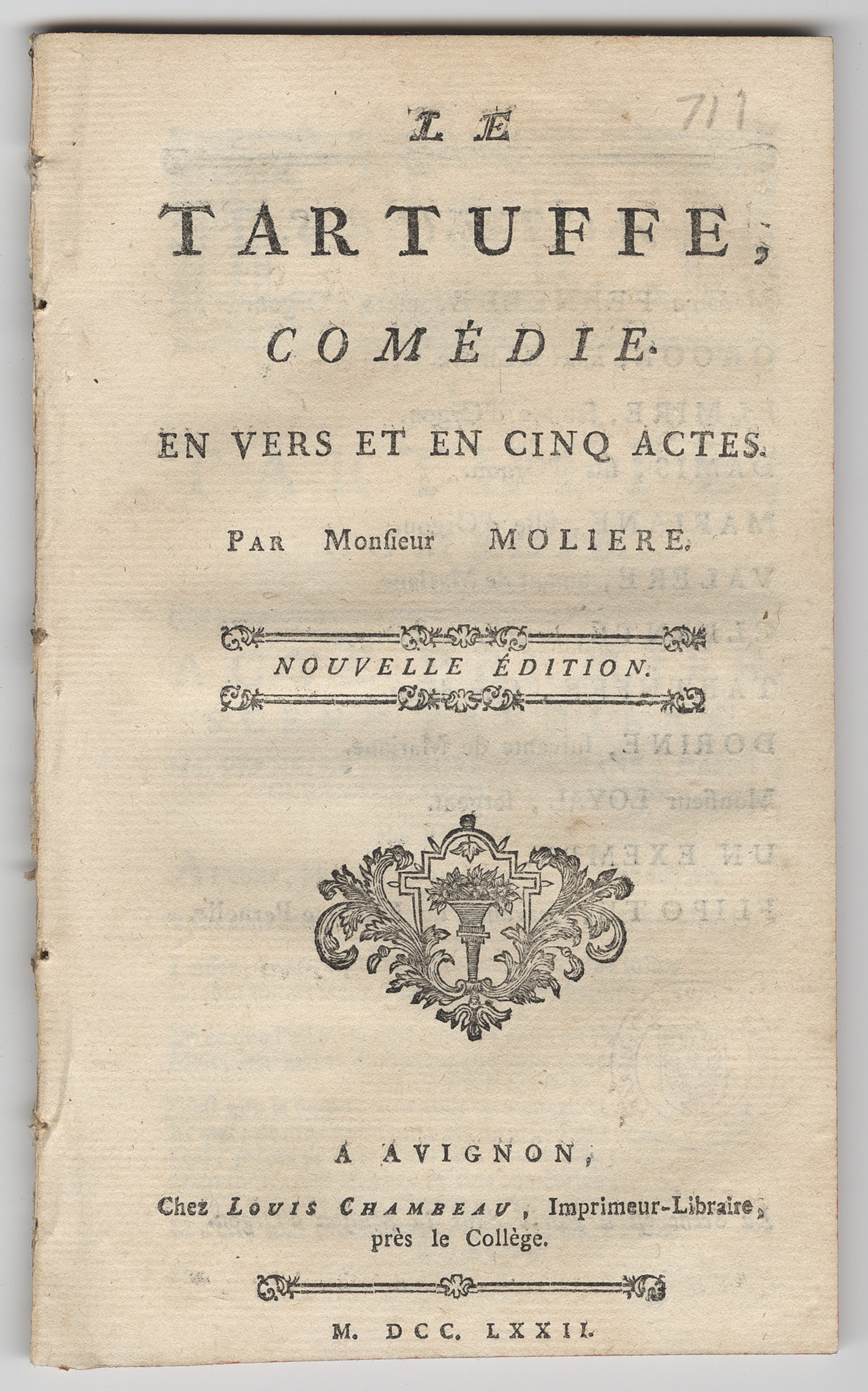

It may be said that censorship was born in Canada in 1694 when the Comte de Frontenac, Governor of Québec decided to ban Molière’s Tartuffe on the advice of the local bishop. While the church in Québec continued to play  an active role in censorship into the twentieth century, it generally fell to customs agents, both before and after Confederation, to determine which literary works, whether books, newspapers, or journals, would be allowed into the territory. The Customs Act of 1847 first prohibited the importation of “books and drawings of an immoral or indecent character,” while Canadian jurisprudence has subsequently turned its attention to combating sedition as well. The difficulty, however, has been to define “obscenity” or “sedition” in a manner that reflects the constantly changing mores of society. Traditionally, customs agents have presented the first line of literary control of imported materials. From 1895 to 1958 officials could refer to a list of proscribed publications to assist them in their decisions to ban materials. Included were such titles as Balzac’s Droll Stories, James T. Farrell’s Bernard Clare, Trotsky’s Chapters from my Diary, Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre, and Grace Metalious’s Peyton Place. The Criminal Code, however, regulates domestic publishing, though it was only during times of crisis that Canadian governments actively pursued a policy of domestic censorship. Otherwise, they have generally supported often vague notions of “community standards.”

an active role in censorship into the twentieth century, it generally fell to customs agents, both before and after Confederation, to determine which literary works, whether books, newspapers, or journals, would be allowed into the territory. The Customs Act of 1847 first prohibited the importation of “books and drawings of an immoral or indecent character,” while Canadian jurisprudence has subsequently turned its attention to combating sedition as well. The difficulty, however, has been to define “obscenity” or “sedition” in a manner that reflects the constantly changing mores of society. Traditionally, customs agents have presented the first line of literary control of imported materials. From 1895 to 1958 officials could refer to a list of proscribed publications to assist them in their decisions to ban materials. Included were such titles as Balzac’s Droll Stories, James T. Farrell’s Bernard Clare, Trotsky’s Chapters from my Diary, Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre, and Grace Metalious’s Peyton Place. The Criminal Code, however, regulates domestic publishing, though it was only during times of crisis that Canadian governments actively pursued a policy of domestic censorship. Otherwise, they have generally supported often vague notions of “community standards.”

The first serious efforts at censorship in Canada occurred during the First World War. The War Measures Act (1914) provided for the “censorship and control and suppression of publications, writings, maps, plans, photographs, communication, and means of communication.” The Chief Censor banned 253 foreign titles, and suppressed several Canadian newspapers which had questioned government policy.

Following the War, fear of socialism pervaded the government and so the War Measures Act was extended to the end of 1919. As a result, much leftist material was banned from importation. While some Canadian journals were suppressed (including The Western Clarion and The Red Flag), the Censor was generally less successful in prosecuting organizations that printed similar materials. General labour discontent spread across Canada in late 1919, and section 98 was added to the Criminal Code establishing a twenty-year prison term for anyone involved in the production or distribution of materials advocating or defending the use of force to achieve political or economic change.

Following the War, fear of socialism pervaded the government and so the War Measures Act was extended to the end of 1919. As a result, much leftist material was banned from importation. While some Canadian journals were suppressed (including The Western Clarion and The Red Flag), the Censor was generally less successful in prosecuting organizations that printed similar materials. General labour discontent spread across Canada in late 1919, and section 98 was added to the Criminal Code establishing a twenty-year prison term for anyone involved in the production or distribution of materials advocating or defending the use of force to achieve political or economic change.

In the inter-war period, bureaucrats focused their attention on printed materials threatening social and political order within their jurisdictions. In Quebec, the “Padlock Law” (1937) made it illegal to propagate Communism in print, and prosecutors were given the right to close printing houses and imprison suspected Communists, with the blessing of the Church, which had traditionally served as censor. The law did not define “propagation” and Ottawa never saw fit to challenge the provincial government’s action; the law remained in place for twenty years.

In 1937 the Social Credit government in Alberta passed the “Press Act” requiring newspapers to print without charge up to one page of Party statements every day a newspaper was printed, and to divulge names of editorial writers. Penalties included suspension of publication and bans against journalists. In 1938, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously proclaimed the  Act unconstitutional.

Act unconstitutional.

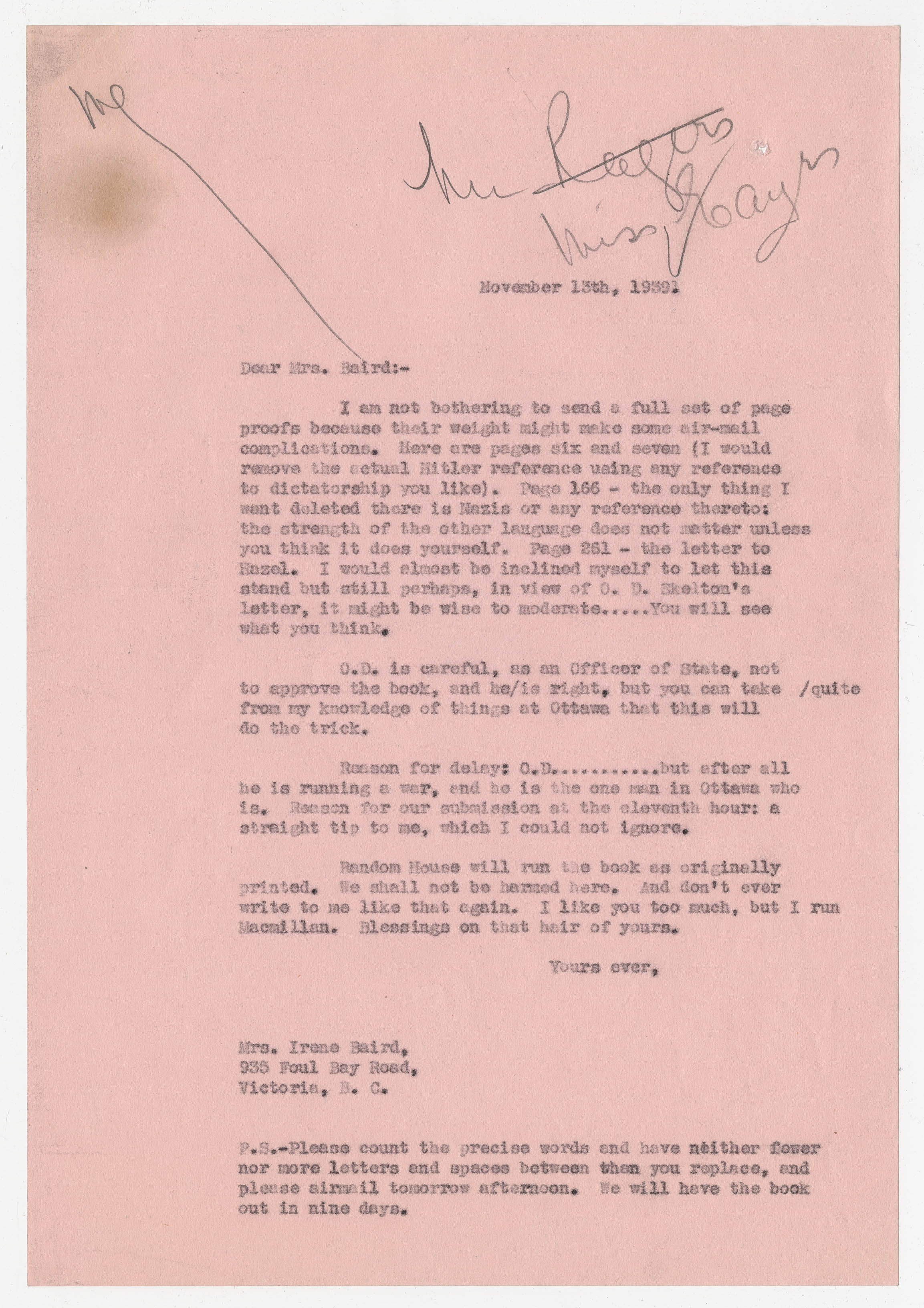

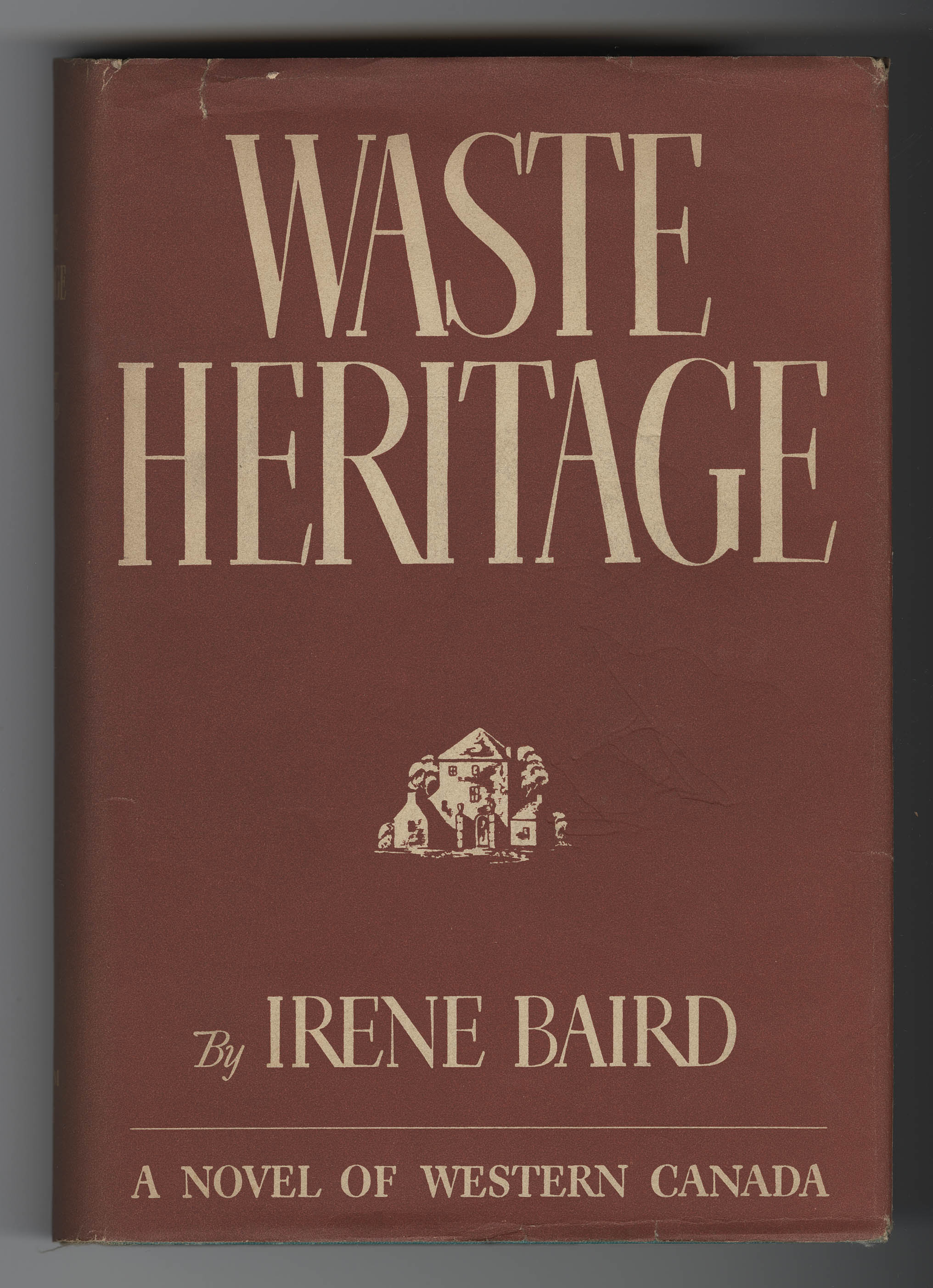

During the Second World War, domestic censorship was voluntary, meaning that editors acted as censors within their own domains, after the War Measures Act and Defence of Canada Regulations came into effect in September 1939. Censorship focused on protecting military secrets and maintaining morale at home. The Chief Censor was never authorized to state positively that any publication was in violation of the Regulations, leading to some confusion especially concerning newspaper reports of troop and logistical information. In time, instructions became more specific: at the war’s peak, about 600 publications were banned by Ottawa. Among them was Irene Baird’s 1939  novel, Waste Heritage which graphically captured the mood among Vancouver’s poor and homeless during sit-down protests of 1938. Owing to its leftist sympathies, the book was censored.

novel, Waste Heritage which graphically captured the mood among Vancouver’s poor and homeless during sit-down protests of 1938. Owing to its leftist sympathies, the book was censored.

In October 1970, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act to deal with the threat that the revolutionary group, the Front de libération du Québec, posed to peace in Canada. The Act allowed for the “censorship and the control and suppression of publications, writings, maps, plans, photographs, communications and means of communication.” After the crisis, Ottawa was criticized for such wide-sweeping control of print during a domestic emergency. The War Measures Act was replaced by the Emergencies Act of  1988 which makes no mention of censorship.

1988 which makes no mention of censorship.

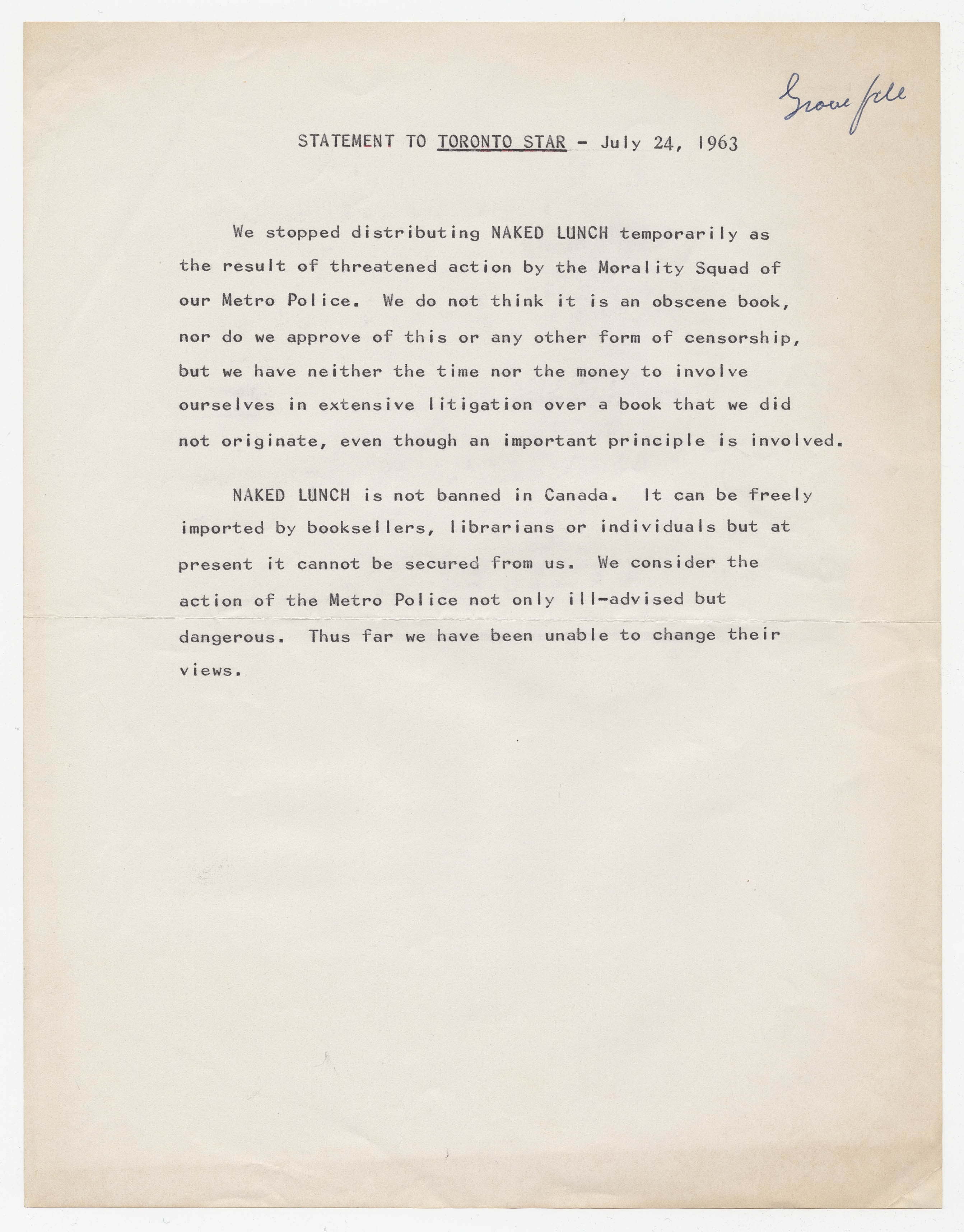

Generally, Canada Customs has enforced the perceived community standards of the day especially with reference to allegedly obscene materials. James Joyce’s Ulysses, for example, was banned from 1923 until 1949 when Maclean’s magazine questioned the detention of a classic. When the uncensored text of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover appeared in 1960, a Montreal judge banned the book, setting aside the expert testimony of Canadian authors Hugh MacLennan and Morley Callaghan. Customs even held up the importation of the book’s British trial transcript because of its explicit details. In 1962 the Supreme Court of Canada  ruled in the book’s favour. William Burrough’s Naked Lunch recounts many of the drug-induced experiences he had while writing in Tangiers; it was banned by numerous countries after it was first published in 1959. In 1963 McClelland & Stewart ceased the distribution of the book in Canada after complaints led to a threat by the Toronto Police Department to seize the title.

ruled in the book’s favour. William Burrough’s Naked Lunch recounts many of the drug-induced experiences he had while writing in Tangiers; it was banned by numerous countries after it was first published in 1959. In 1963 McClelland & Stewart ceased the distribution of the book in Canada after complaints led to a threat by the Toronto Police Department to seize the title.

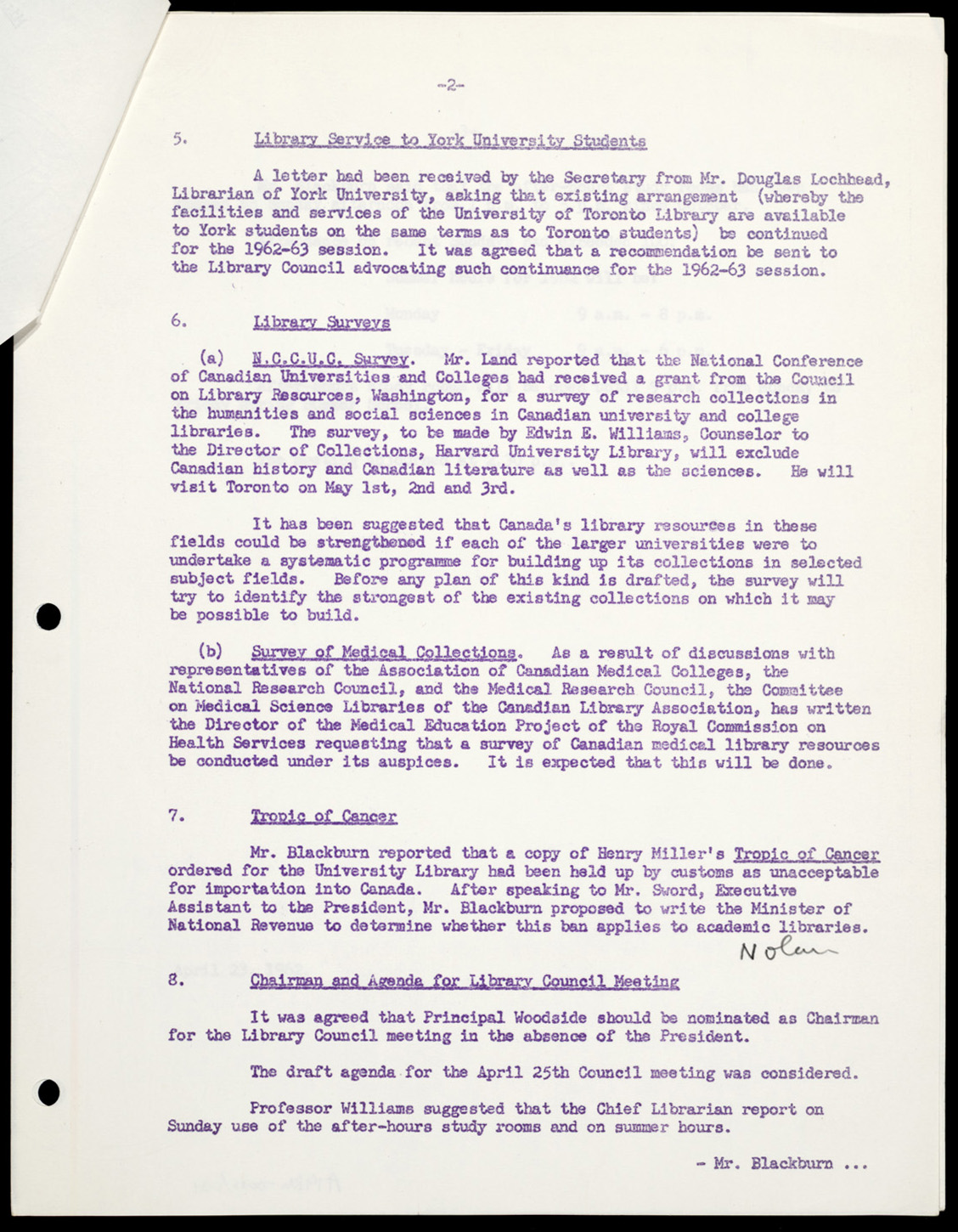

In 1949 ninety-seven titles, including Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, which the Minister of National Revenue banned without reading, were excluded from Canada for obscenity. A similar fate befell the writings of Henry Miller. In 1959, the government amended the Criminal Code,  describing obscene literature as “any publication a dominant characteristic of which is the undue exploitation of sex, or of sex and any one or more of the following subjects, namely, crime, horror, cruelty and violence”

describing obscene literature as “any publication a dominant characteristic of which is the undue exploitation of sex, or of sex and any one or more of the following subjects, namely, crime, horror, cruelty and violence”

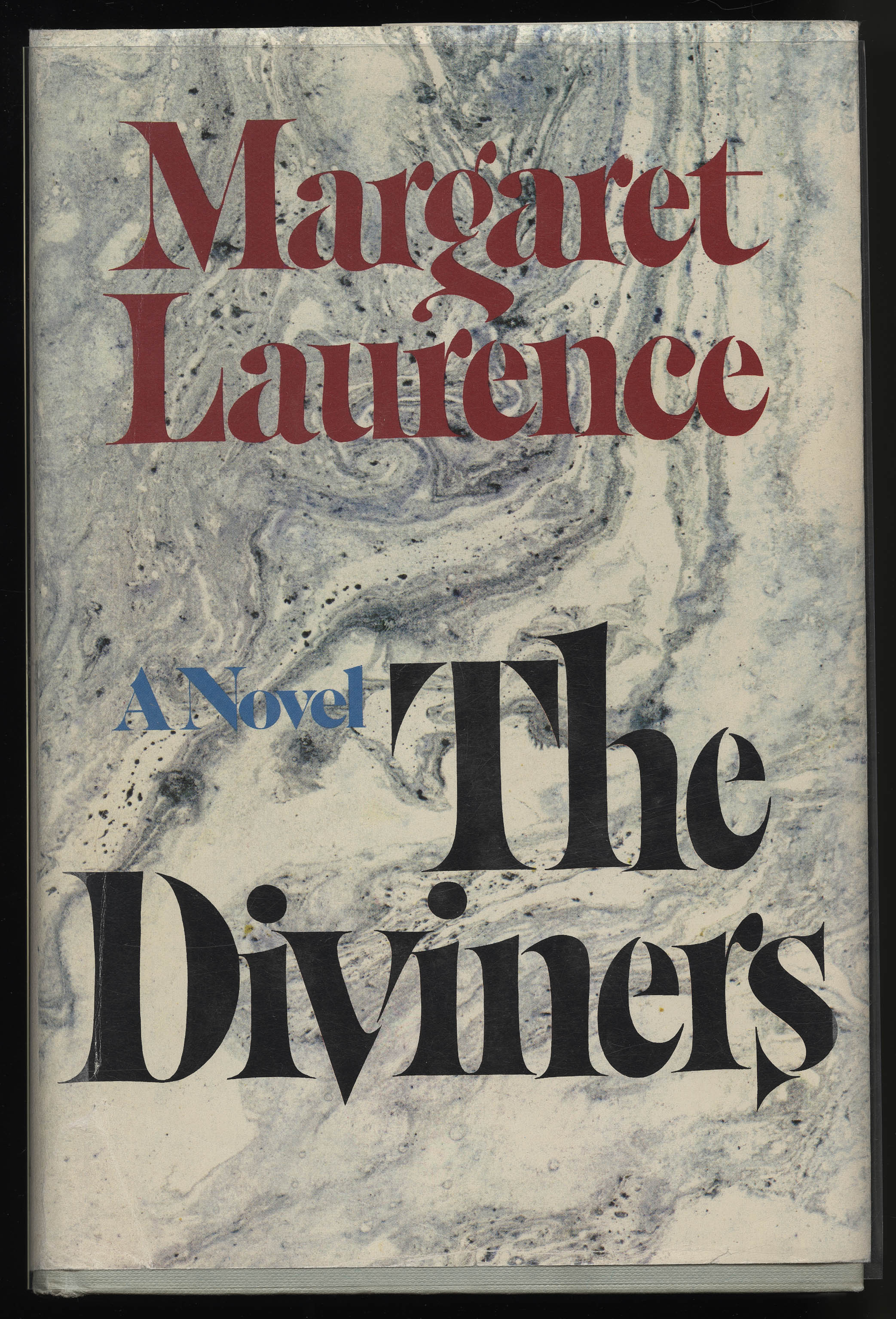

Proof-texting – the use of out-of-context quotations to support a particular viewpoint – remains a legal means to prosecute books and those associated with them. It has proven popular with parent groups which, especially in the 1970s, sought control over school libraries and reading lists. In 1976, a group of Lakefield, Ontario parents demanded that Margaret Laurence’s The Diviners be removed from schools as “unsavory pornography.” A similar challenge came in 1985 from another group which  acknowledged that they had not read the book in its entirety. Complaints have also been raised by parent councils against Morley Callaghan’s Such is my Beloved, W.O. Mitchell’s Who has seen the Wind? and Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women, to name but three.

acknowledged that they had not read the book in its entirety. Complaints have also been raised by parent councils against Morley Callaghan’s Such is my Beloved, W.O. Mitchell’s Who has seen the Wind? and Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women, to name but three.

As the 1980s approached it was clear that censorship was increasingly focused on the protection of family values, religious, and minority rights. With the appearance of the Charter of Rights (1982), however, limitations on literary expression would become far more difficult to justify. Nevertheless, customs agents have continued to operate in accord with the spirit of the earliest tariff laws, confiscating shipments of books intended for stores like Little Sister’s in Vancouver, Glad Day and Wonderworks in Toronto, and Androgyne in Montreal, based solely on the judgment of individual border guards. In 1990, for example, several boxes containing Jane Rule’s The Young in One Another’s Arms was seized by a Customs agent for obscenity while en route to Little Sister’s. Testifying on behalf of the store in 1994, Rule reflected that “every time this issue comes up, whether I were testifying in this trial or not, my name would come up over and over again as that woman whose books are seized at the border, and I have no defence against it. And I bitterly resent the attempt to marginalize, trivialize and even criminalize what I have to say because I happen to be a lesbian, I happen to be a novelist, I happen to have bookstores and publishers who are dedicated to producing my work. The assumption that there must be something pornographic [in my writing] because of my sexual orientation is a shocking way to deal with my community.” In 2000, the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the right of Canada Customs to inspect and seize “sexually obscene” materials but also criticized them for focussing on materials with gay themes, particularly those imported by gay and lesbian booksellers.

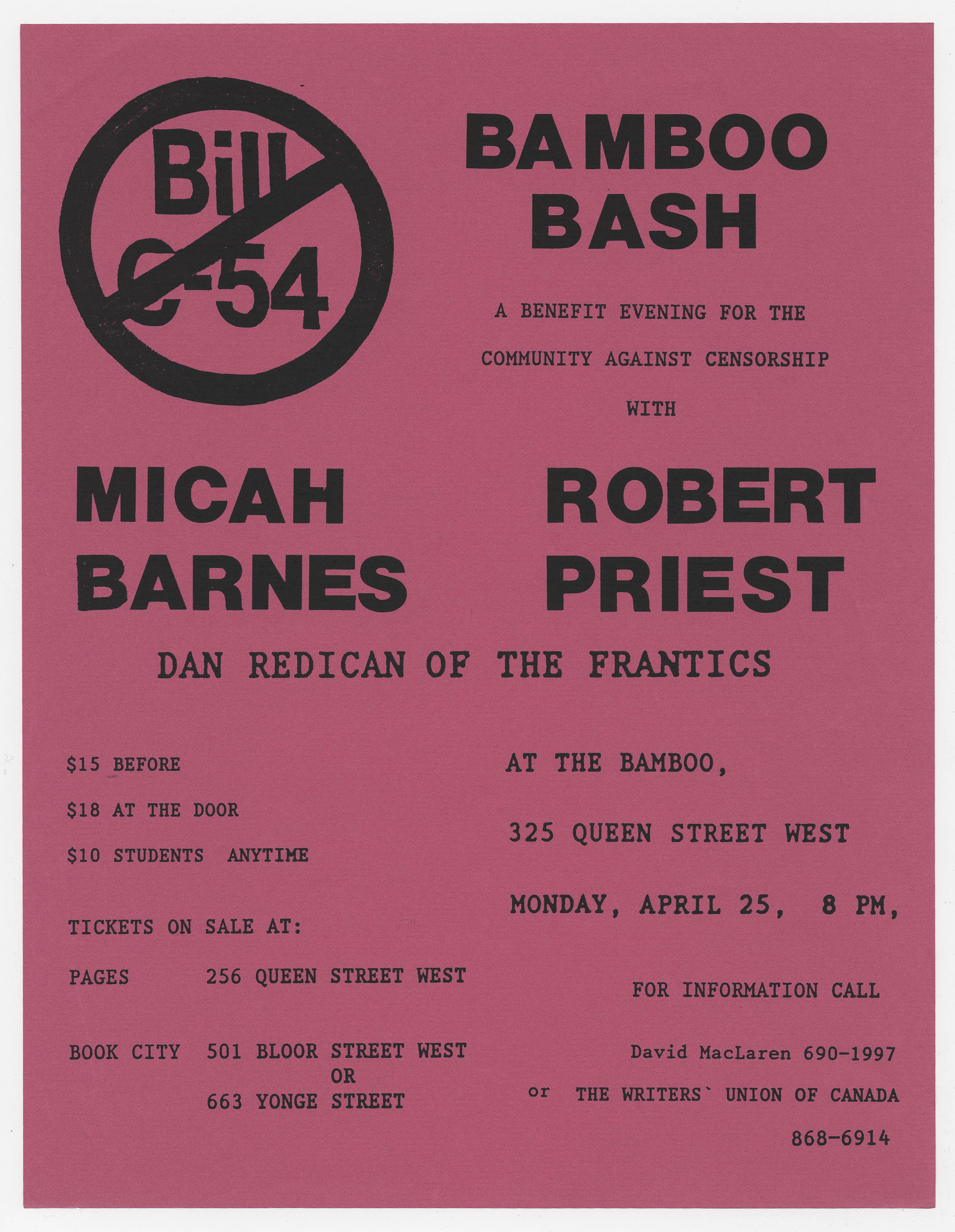

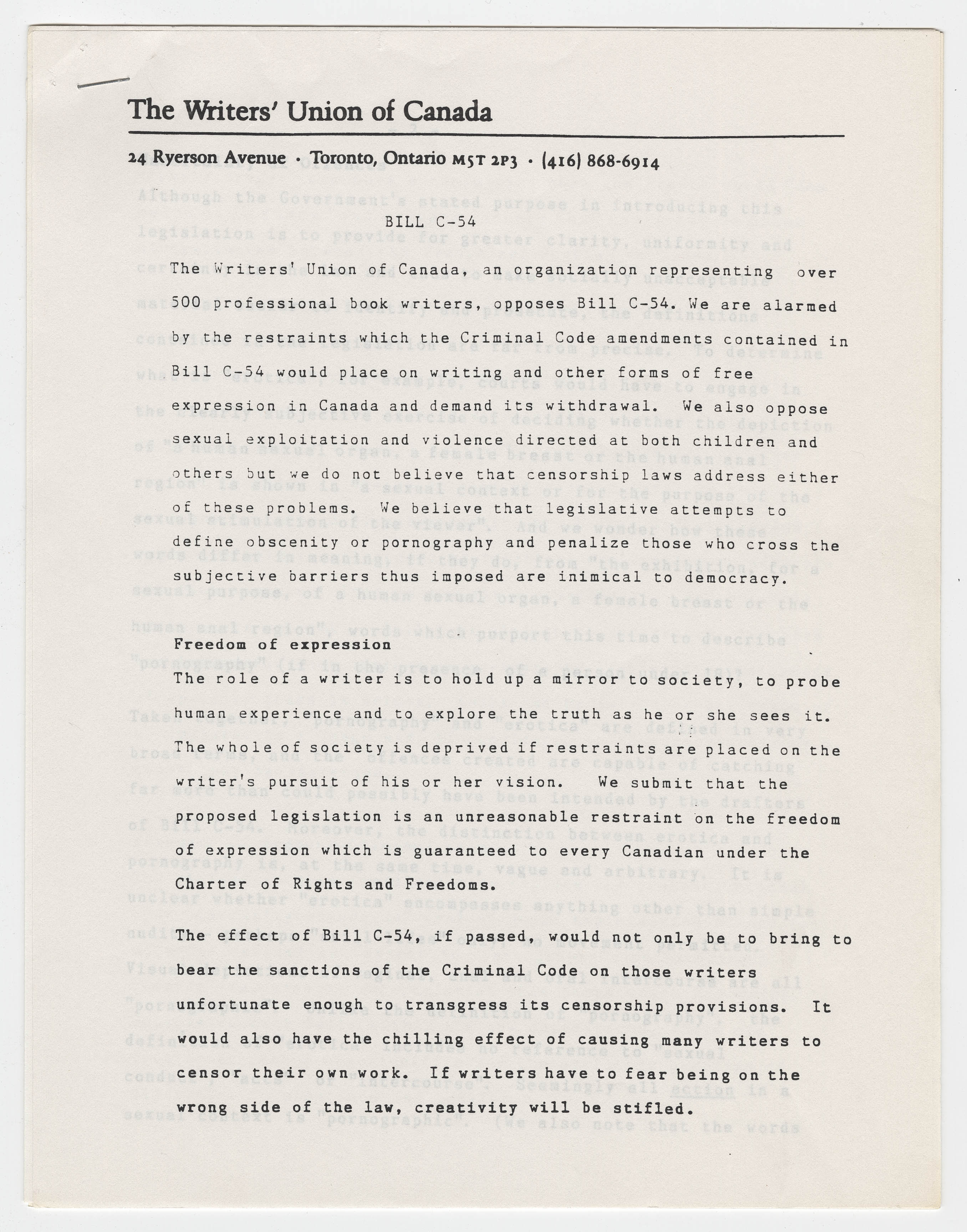

Literary organizations are increasingly on the forefront in  the fight to protect the rights of authors and booksellers against those who would censor them. PEN Canada was established in 1921 and continues to intercede for authors and readers at home and abroad. The Writers’ Union of Canada was established in 1973 to advocate on behalf of published authors and has been consistently involved in anti-censorship activities, most notably in the 1987 resistance to Bill C-54, an “anti-pornography” measure that threatened literary expression. It was in the wake of a 1978 attack upon Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women that the Freedom of Expression Committee of the Book and Periodical Council was established. This group has annually sponsored “Freedom to Read Week” activities throughout the country to raise awareness of the threats of censorship to democracy.

the fight to protect the rights of authors and booksellers against those who would censor them. PEN Canada was established in 1921 and continues to intercede for authors and readers at home and abroad. The Writers’ Union of Canada was established in 1973 to advocate on behalf of published authors and has been consistently involved in anti-censorship activities, most notably in the 1987 resistance to Bill C-54, an “anti-pornography” measure that threatened literary expression. It was in the wake of a 1978 attack upon Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women that the Freedom of Expression Committee of the Book and Periodical Council was established. This group has annually sponsored “Freedom to Read Week” activities throughout the country to raise awareness of the threats of censorship to democracy.

The greatest challenge facing contemporary Canadian censors is without doubt the Internet. The attempt to control what people read has never been as futile as it is now when so much text and so many images have their principal home in an unregulated cyberspace. The Internet may actually force governments, schools, and families to initiate conversations about what is appropriate for reading and viewing and what is not – and and more importantly, why – when in the past they would simply have issued a general ban and considered their duty done.

University of Toronto Archives and Record Management Services, University of Toronto

Writers’ Union of Canada fonds, McMaster University