An “Artist of standing”: C.W. Jefferys and Historical Illustration in Canada

Eric Weichel, Queen’s University

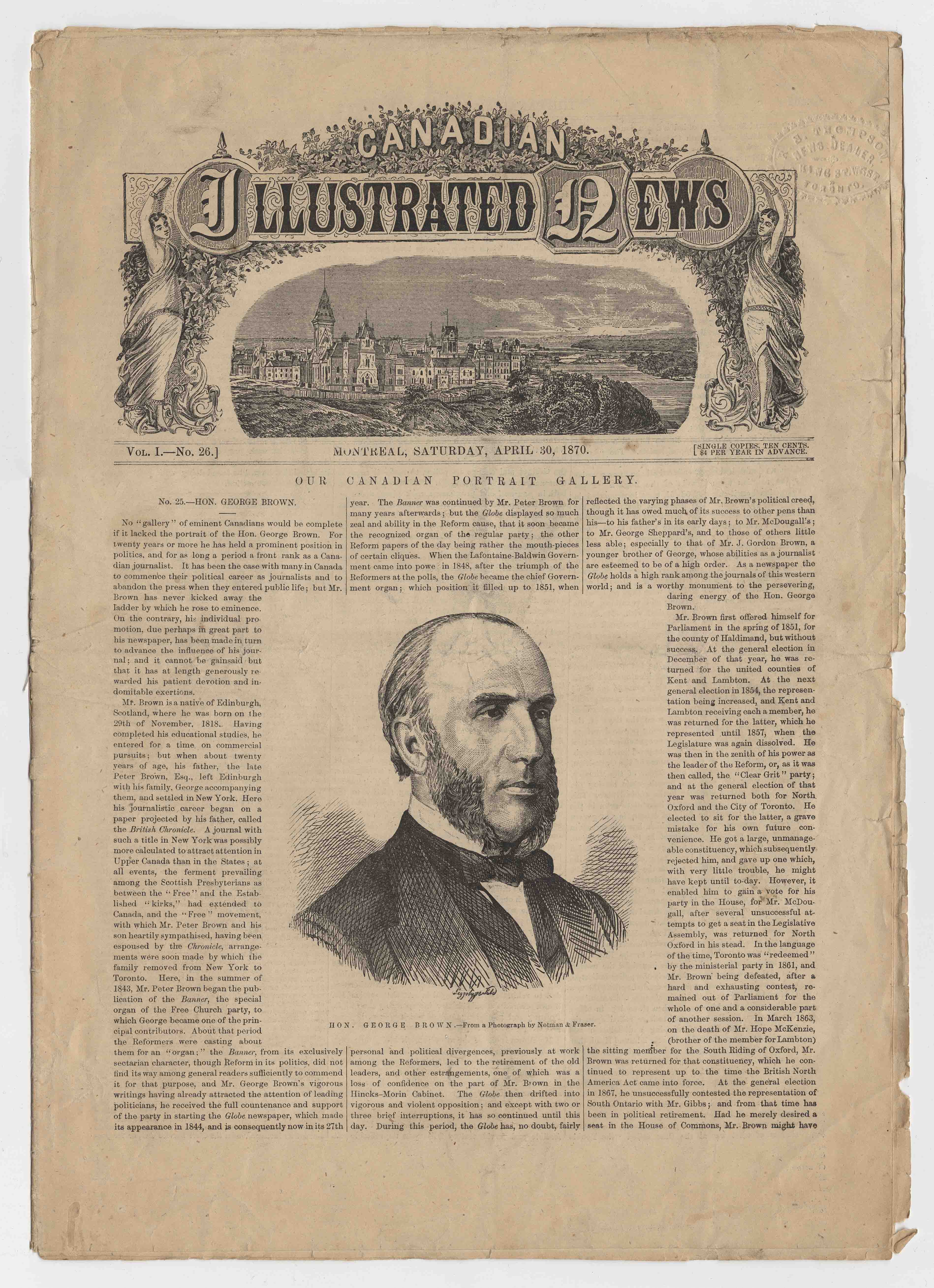

In nineteenth-century Canada,  opportunities for artists to create illustrations for a national audience remained few in number until the Canadian Illustrated News of the 1870s included works by William Armstrong, William Cruickshank, F.M. Bell Smith, and Henri Julien. In 1882, Picturesque Canada, edited by George Munro Grant, became one of the first illustrated publications dedicated to Canadian themes. Ambitious in scope, the volume reproduced scenes of the “sublime” Canadian landscape through the process of wood-engraving.

opportunities for artists to create illustrations for a national audience remained few in number until the Canadian Illustrated News of the 1870s included works by William Armstrong, William Cruickshank, F.M. Bell Smith, and Henri Julien. In 1882, Picturesque Canada, edited by George Munro Grant, became one of the first illustrated publications dedicated to Canadian themes. Ambitious in scope, the volume reproduced scenes of the “sublime” Canadian landscape through the process of wood-engraving.

In 1886, several young artists founded the Toronto Art Students League, a seminal group that used innovative technical processes such as photoengraving. An attractive and skilfully produced calendar issued by the  League from 1892 to 1904 is seen as a turning point in Canadian illustration and book design. As Sybil Pantazzi notes, the calendar brought attention to Canadian artists, encouraging publishers to employ resident illustrators instead of foreign professionals. The League also stimulated the coalescence of a group of artists, including Norman Price, William Wallace, and Thomas Garland Greene, who would go on to specialize in book design. Among this group was the young C.W. Jefferys.

League from 1892 to 1904 is seen as a turning point in Canadian illustration and book design. As Sybil Pantazzi notes, the calendar brought attention to Canadian artists, encouraging publishers to employ resident illustrators instead of foreign professionals. The League also stimulated the coalescence of a group of artists, including Norman Price, William Wallace, and Thomas Garland Greene, who would go on to specialize in book design. Among this group was the young C.W. Jefferys.

Charles William Jefferys (1869-1951), one of the League’s earliest members, was born in Rochester, England, and immigrated to Canada with his family, settling in Toronto by 1880. Jefferys started his career as an artist in 1886, when he began a five-year apprenticeship with the Toronto Lithographic Co. His involvement with the League inaugurated a lifelong career of artistic, literary, and academic distinction in Canada.

Canadian history textbooks from the first fifty years of the twentieth century are full of examples of Jefferys’s brisk, evocative pen sketches, many of which reconstruct formative moments in the nation’s past. Created in a flourishing style that amply demonstrates both his intimate, accurate knowledge of history and his mastery of the medium of ink, Jefferys’s work is particularly notable in numerous textbooks on Canadian and British history, created for public and high schools by historian George M. Wrong; in over 200 illustrations, maps, and charts for The Ryerson Canadian History Readers; and in Dramatic Episodes in Canada’s History, a popular volume first issued by the Toronto Star in 1930. Notes by Lorne Pierce in his manuscript collection at Queen’s University Archives indicate this volume was revised, enlarged, and reissued in 1934 by Ryerson Press. The culmination of Jefferys’s contributions to reconstructing the past was The Picture Gallery of Canadian History: Illustrations Drawn and Collected by C.W. Jefferys, a primarily illustrated volume which was first published by Ryerson in 1942, subsequently running to three volumes over eight years. The work was viewed, both by Jefferys and Pierce, his Ryerson editor, as the crowning achievement of his publishing career.

Aside from work as a book illustrator, Jefferys also contributed regularly to the Canadian History Review, was a figurehead and frequent speaker for the historical societies of Ontario, was president of various antiquarian societies, and sat on the Royal Canadian Academy’s council. He designed the Tyrell Medal of the Royal Society of Canada and the Jubilee Medal of Canadian Confederation. His murals adorn three of the nation’s most prestigious buildings: the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, and two luxury hotels: the Chateau Laurier in Ottawa, and Le Manoir Richelieu in the Charlevoix.

In recognition of his interdisciplinary accomplishments in commercial publishing, literary and scholarly endeavours, and visual art, Jefferys was elected as a full Academician of the Royal Canadian Academy, and received an Honorary Doctor of Laws from Queen’s University. Pierce notes that Jefferys was also “made an honorary chief of the Mohawks at Brantford, and given the name Ga–re–wa–ga-yon – Historical Words” by the Mohawk community (now the Kanien’Kahake Six Nations of the Grand River). His letters and speeches, some preserved in the Pierce collection at Queen’s, are testimonials to the depth and breadth of his astonishing career.

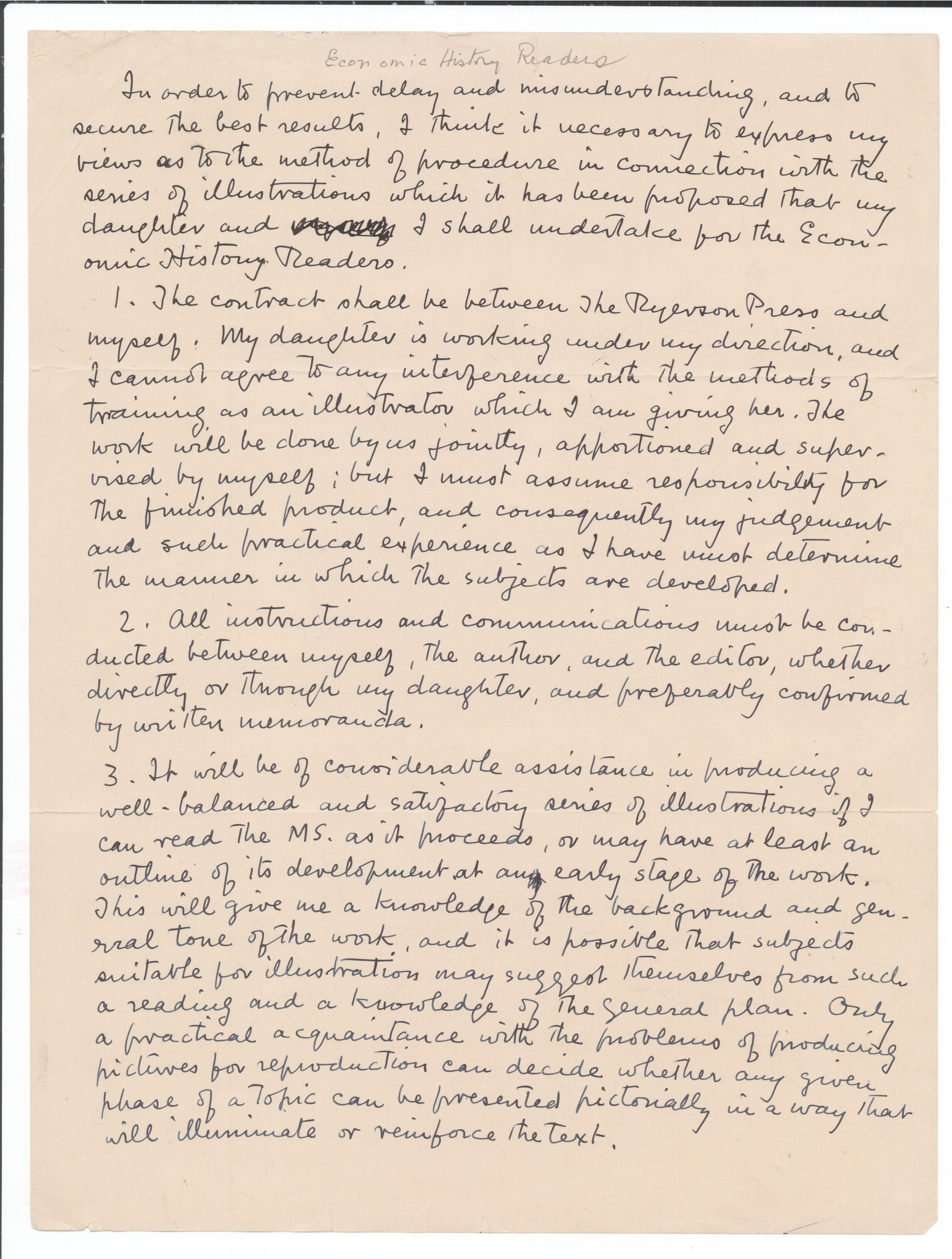

Part of Jefferys’s success rested on his canny skills as a confident negotiator, and his emphasis on personal control over his work. For example, in an undated letter to Ryerson, Jefferys stipulates conditions he requires to accept a commission for a “series of illustrations it has been proposed that my daughter and I shall undertake for the Economic History Reader.” Jefferys states: “my daughter is working under my direction, and I cannot agree to any interference with the methods and training I am giving her.” He assumes direct responsibility for the finished product and stipulates that all communication from the publisher must be limited to a select number of people. He must have early access to finished manuscripts and demands that an outline must be provided to him as work proceeds. Jefferys asserts that, while the editor’s suggestions of historical data and pictorial sources “will be welcomed and carefully considered,”

Part of Jefferys’s success rested on his canny skills as a confident negotiator, and his emphasis on personal control over his work. For example, in an undated letter to Ryerson, Jefferys stipulates conditions he requires to accept a commission for a “series of illustrations it has been proposed that my daughter and I shall undertake for the Economic History Reader.” Jefferys states: “my daughter is working under my direction, and I cannot agree to any interference with the methods and training I am giving her.” He assumes direct responsibility for the finished product and stipulates that all communication from the publisher must be limited to a select number of people. He must have early access to finished manuscripts and demands that an outline must be provided to him as work proceeds. Jefferys asserts that, while the editor’s suggestions of historical data and pictorial sources “will be welcomed and carefully considered,”  the artist “must be free to accept or reject” such suggestions as he sees fit, noting that “only a practical acquaintance with the problems of producing pictures for reproduction can decide whether any given phrase or topic can be presented pictorially in a way that will illuminate or reinforce the text.” He concedes: “in such cases I must give reasons for my decisions.”

the artist “must be free to accept or reject” such suggestions as he sees fit, noting that “only a practical acquaintance with the problems of producing pictures for reproduction can decide whether any given phrase or topic can be presented pictorially in a way that will illuminate or reinforce the text.” He concedes: “in such cases I must give reasons for my decisions.”

Jefferys concludes this letter by refusing to provide free preliminary sketches for approval: “in the case of rejection or virtual reconstruction of such sketches, they shall be paid for at the rate of 50 % the price of accepted finished drawings,” as “free speculative sketches are contrary to the ethics of professional practice, and are condemned by artists of standing.”

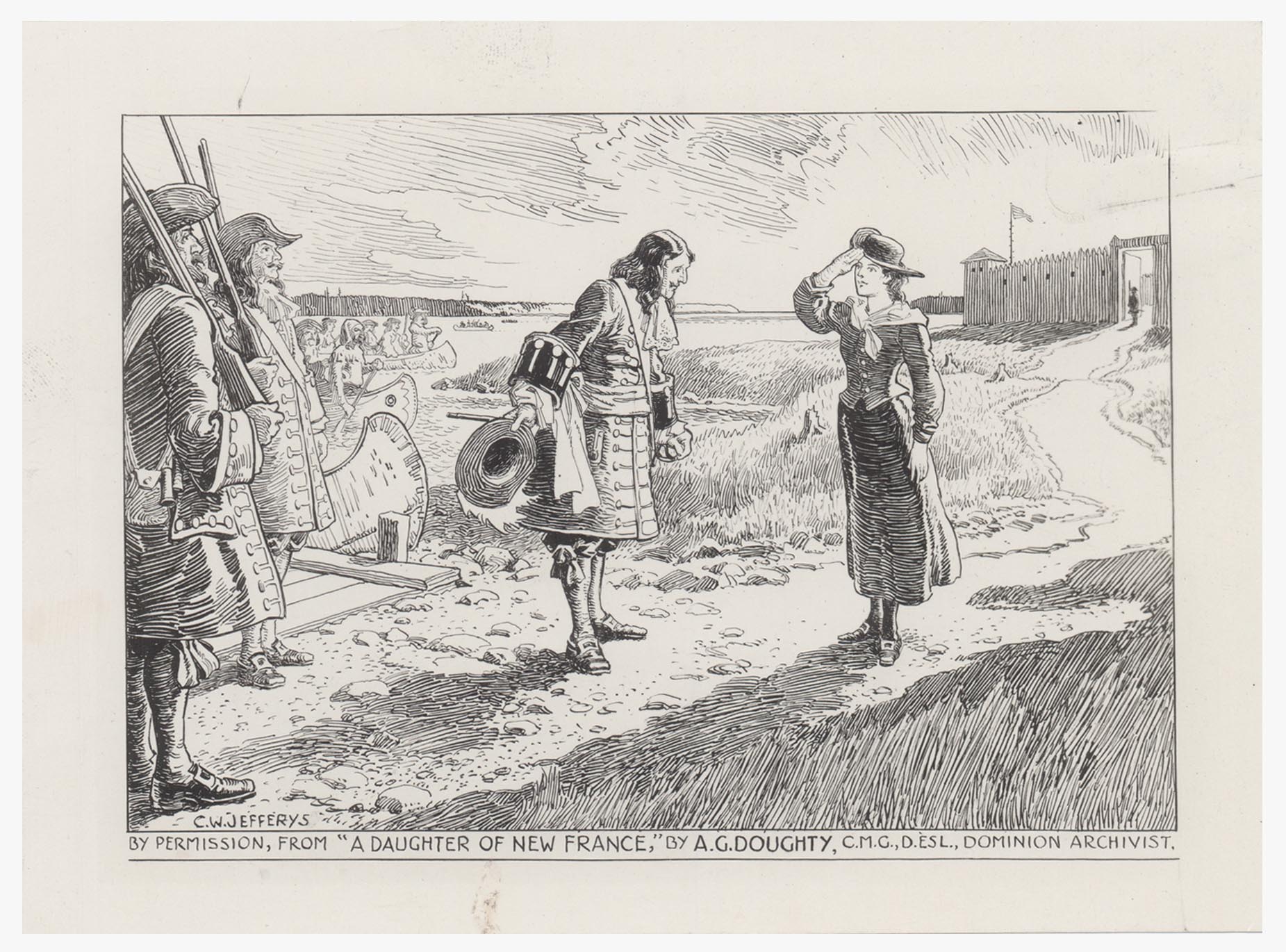

Jefferys’s images are distinguished by a prescient interest in the greater sphere of material culture, as opposed to just “fine art,” as his work, especially historical illustrations, shows an insightful interest in the social meaning of costume, anticipating a later, feminist, re-appropriation of craft and textiles. For example, the whirling drapery in Jefferys’s portrait of Madeleine de Verchères highlights the subject’s autonomy and leadership in a time of crisis, displaying a sensitivity paralleled in some of the speeches he gave for the Historical Society of Ontario.

Jefferys’s images are distinguished by a prescient interest in the greater sphere of material culture, as opposed to just “fine art,” as his work, especially historical illustrations, shows an insightful interest in the social meaning of costume, anticipating a later, feminist, re-appropriation of craft and textiles. For example, the whirling drapery in Jefferys’s portrait of Madeleine de Verchères highlights the subject’s autonomy and leadership in a time of crisis, displaying a sensitivity paralleled in some of the speeches he gave for the Historical Society of Ontario.

Other aspects of his work are less sensitive. The reverential attitude to the Victorian patriarchate, evident in some of his printed speeches, contrasts with his treatment of Aboriginal males in his history-piece illustrations. As many post-colonial writers, including Cecilia Morgan, have noted, numerous depictions of Native American masculinity in western graphic illustration are disturbingly fetishistic, violent, spectatorial and sexualized.

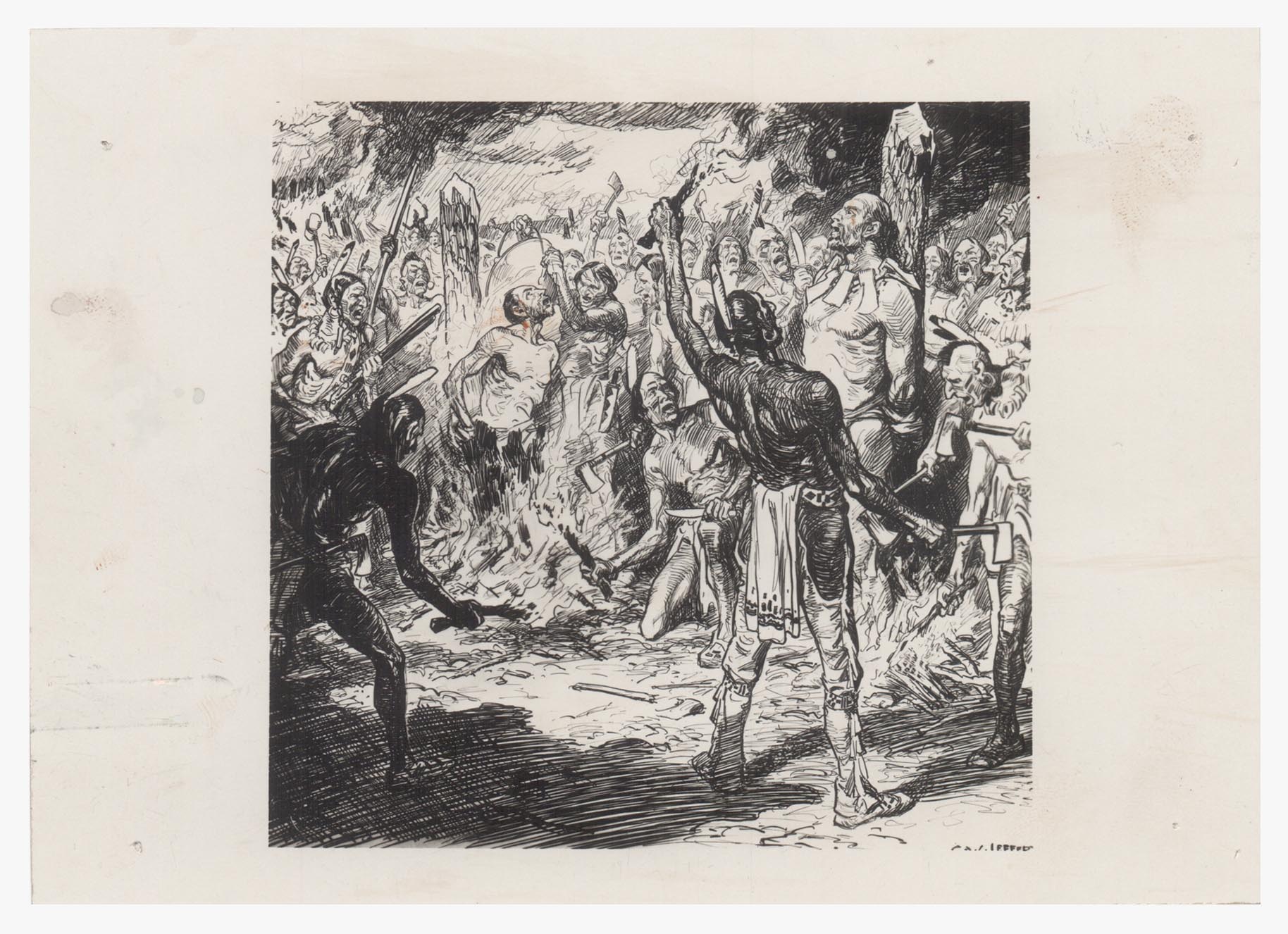

Morgan’s model of criticism is quite poignant when applied to Jefferys’s Martyrdom of Brébeuf and Lallemont, an imaginative reconstruction of events surrounding the 1649 execution of two French proselytes by Native warriors. Part of this image’s visceral appeal is in the brilliant handling of the compositional space, crowded with figures, each contorted into complicated poses that accentuate the drama and horror of this moment. Jefferys’s visual language in describing the martyrs’ sufferings—the one exhorting the other to rational self-control even in the midst of an excruciating death—is completely opposite to his treatment of the Iroquois, who are depicted en masse,

Morgan’s model of criticism is quite poignant when applied to Jefferys’s Martyrdom of Brébeuf and Lallemont, an imaginative reconstruction of events surrounding the 1649 execution of two French proselytes by Native warriors. Part of this image’s visceral appeal is in the brilliant handling of the compositional space, crowded with figures, each contorted into complicated poses that accentuate the drama and horror of this moment. Jefferys’s visual language in describing the martyrs’ sufferings—the one exhorting the other to rational self-control even in the midst of an excruciating death—is completely opposite to his treatment of the Iroquois, who are depicted en masse,  indistinguishable and interchangeable, a collective utterly lost to the deepest ravages of their passions; indeed, a note by Jefferys on the verso of a reproduction of this print characterizes the aboriginal band as “howling Mohawks,” contrasting with his differentiated description of the physical characteristics of the two European men. The priests are represented as individuals, but the Mohawks are understood only in terms that, as Morgan observes, exaggerate ethnic and sexual difference. How different from Jefferys’s account of Victorian statesmen in “Clothes and History,” read for the Head-of-the-Lake Historical Society on 12 April 1946, where dignified, if portly, masculine bodies were swathed in double-breasted suits of sober hue, ready for the individual exercise of power!

indistinguishable and interchangeable, a collective utterly lost to the deepest ravages of their passions; indeed, a note by Jefferys on the verso of a reproduction of this print characterizes the aboriginal band as “howling Mohawks,” contrasting with his differentiated description of the physical characteristics of the two European men. The priests are represented as individuals, but the Mohawks are understood only in terms that, as Morgan observes, exaggerate ethnic and sexual difference. How different from Jefferys’s account of Victorian statesmen in “Clothes and History,” read for the Head-of-the-Lake Historical Society on 12 April 1946, where dignified, if portly, masculine bodies were swathed in double-breasted suits of sober hue, ready for the individual exercise of power!

As Sandra Campbell notes, Jefferys is to be praised for the sensitivity and prescience of his carefully-researched and highly evocative visions of the historical landscape, as his images attempt to collapse boundaries of time and space, offering a template of the past that strives for photographic accuracy. It is this constructed accuracy, this archaeology of fashion and setting, that adds appeal to his images, even if ethno-sexual stereotyping did inform his work. Jefferys’ art and writing are important records of the fraught history of colonialism, cultural interaction and ethnic tension that went into the making of modern Canada. In the words of his mentor Lorne Pierce, “no Canadian is more secure in the affection of both English and French in this country, or more certain of an abiding place in the history of Canada, a history which he has done so much to interpret, adorn and make live again.”

Campbell, Sandra. “From Romantic History to Communications Theory: Lorne Pierce as Publisher of C. W. Jeffreys and Harold Innis.” Journal of Canadian Studies 30.3 (1995): 91-117.

Morgan, Cecilia. “History, Nation and Empire: Gender and Southern Ontario Historical Societies, 1890s-1920s.” Canadian Historical Review 82.3 (September, 2001): 491-528.

Pantazzi, Sybille. “Book Illustration and Design By Canadian Artists 1890-1940 with a List of Books Illustrated by Members of the Group of Seven,” National Gallery of Canada / Bulletin de la Galerie nationale du Canada 7 (1966): 6-24, 30, 31.

Stacey, Robert. “Jefferys, Charles William.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available online at: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA…

Lorne and Edith Pierce collection, Queen’s University Archives