Agnes FitzGibbon’s Subscription Books for Canadian Wild Flowers

Alexander Globe, University of British Columbia

In nineteenth-century Canada, small populations left publishers scant marketing options. The 1871 census counted just 160,000 people in Montreal and 56,092 in Toronto. Newspapers, government documents, and school texts could turn profits, but more specialized books often lost money given the few potential customers. Publishers often placed the burden of risk with authors by insisting on subscribed presales to cover production costs. The authors usually made a pittance.

As a child, Agnes FitzGibbon (1833-1913) had watched her mother, Susanna Moodie, née Strickland (1803-85), paint watercolours of bouquets. To earn much needed cash after she was widowed, FitzGibbon took up a request to illustrate flowers for a botanical work by her aunt, Catharine Parr Traill, née Strickland (1802-99). In November 1866, John Lovell of Montreal agreed to publish a book if the women supplied the illustrations and pre-sold 500 copies. The $5 cost was high—five times what Lovell charged for substantial volumes without pictures. (For more details, see the case study, “The Story of Canadian Wild Flowers.”)

FitzGibbon sprang into action with breathtaking determination. In February 1867, Lovell provided her with a specimen book of the kind that salesmen took  door to door. The volume, now in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto, was very large by Canadian standards—36 x 28.5 cm. The design on forest green cloth reinforced growing national sentiment: it features gilt ornaments of Jacques Cartier and a beaver framing the glimmering title, CANADIAN | W ILD FLOWERS. Inside are two stubs which previously held flower paintings. Three pages of text describe a lady’s slipper, wild orange lily, and wintergreen. On 20 June 1867, Traill wrote that in just four months, over 400 subscribers had been recruited, mainly from Toronto. FitzGibbon’s Toronto patrons fill sixteen manuscript pages. Pencilled numbers in the left margin tally 562 copies. After these entries, six separate pages of names collected by someone else in Belleville are sewn into the subscription book. The postal wrapper used by Traill to send the material to FitzGibbon is preserved with this second portion of the book.

door to door. The volume, now in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto, was very large by Canadian standards—36 x 28.5 cm. The design on forest green cloth reinforced growing national sentiment: it features gilt ornaments of Jacques Cartier and a beaver framing the glimmering title, CANADIAN | W ILD FLOWERS. Inside are two stubs which previously held flower paintings. Three pages of text describe a lady’s slipper, wild orange lily, and wintergreen. On 20 June 1867, Traill wrote that in just four months, over 400 subscribers had been recruited, mainly from Toronto. FitzGibbon’s Toronto patrons fill sixteen manuscript pages. Pencilled numbers in the left margin tally 562 copies. After these entries, six separate pages of names collected by someone else in Belleville are sewn into the subscription book. The postal wrapper used by Traill to send the material to FitzGibbon is preserved with this second portion of the book.

Agnes’s legendary beauty and vivacity helped bring in subscribers, but she also had a shrewd sense of sales strategy. Her first stop was Osgoode Hall in Toronto, where her late husband had been surrogate clerk in Chancery from 1862-5. The first five names on the list are Chief Justices Draper and Richards,  followed by three other justices. Whether they knew Agnes well or were simply taking pity on her, their signatures stood at the head of the list, a strong incentive to others, who likely could not resist subscribing into that illustrious company. Several lawyers and Osgoode connections signed up (nos. 23-30, 138-9). Not to be left out, Sheriff Fred. W. Jarvis subscribed, as did the mayor, George Brown, and the John Macdonald who would soon be prime minister of Canada (nos. 151, 66, 20-1, and 157). John Hilton (no. 35), FitzGibbon’s Anglican rector, may have helped open the doors to the Bishops of Niagara and Toronto (nos. 144-5) and other clergy. Among academics, William Hincks and Daniel Wilson of University College each purchased a copy (nos. 12 and 15).

followed by three other justices. Whether they knew Agnes well or were simply taking pity on her, their signatures stood at the head of the list, a strong incentive to others, who likely could not resist subscribing into that illustrious company. Several lawyers and Osgoode connections signed up (nos. 23-30, 138-9). Not to be left out, Sheriff Fred. W. Jarvis subscribed, as did the mayor, George Brown, and the John Macdonald who would soon be prime minister of Canada (nos. 151, 66, 20-1, and 157). John Hilton (no. 35), FitzGibbon’s Anglican rector, may have helped open the doors to the Bishops of Niagara and Toronto (nos. 144-5) and other clergy. Among academics, William Hincks and Daniel Wilson of University College each purchased a copy (nos. 12 and 15).

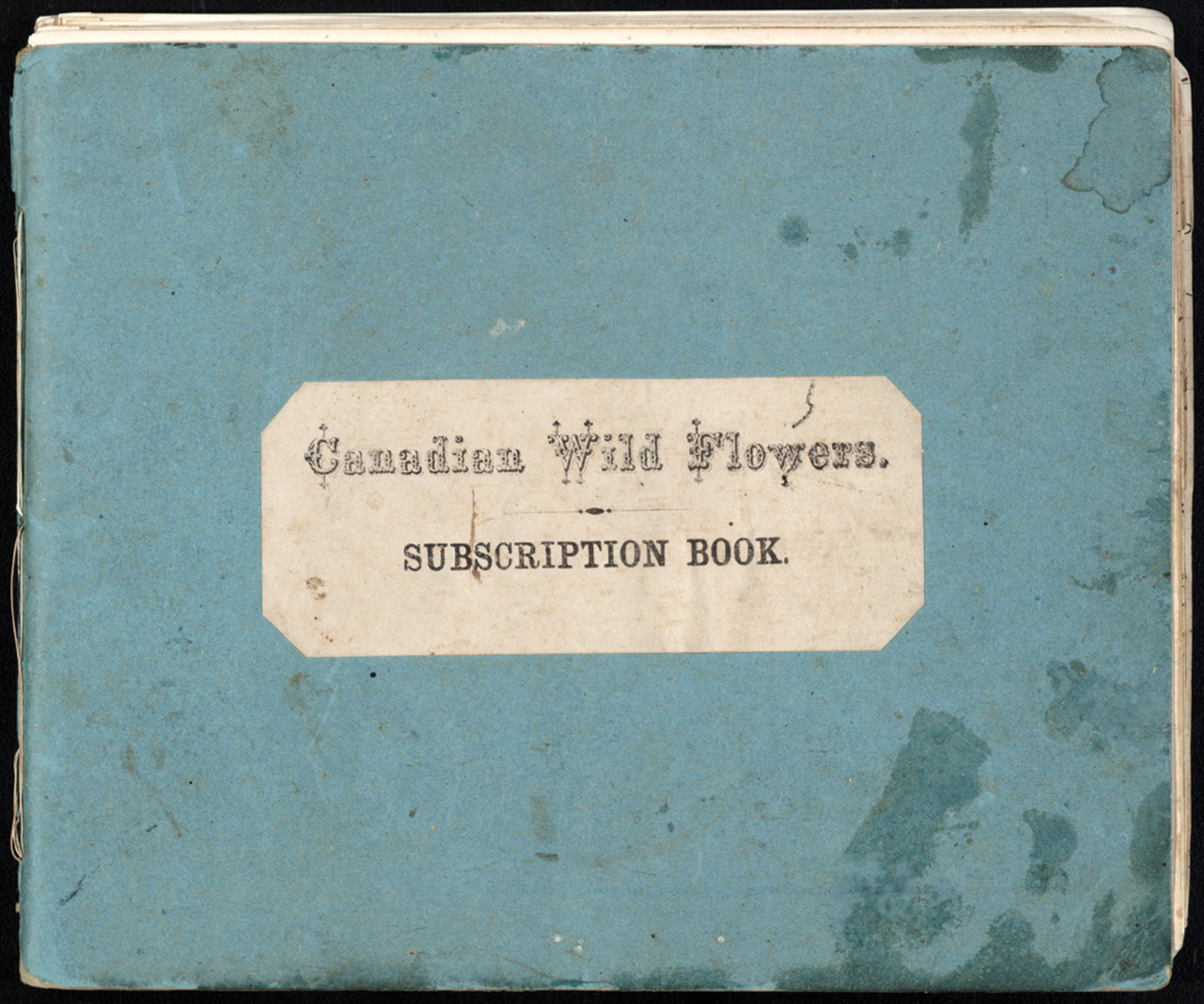

The Fisher collection also contains a small notebook (16.4 x 20 cm) titled “Canadian Wild Flowers. [rule] SUBSCRIPTION BOOK”, which FitzGibbon took with a copy of Canadian Wild Flowers on later recruiting forays. Subscribers, mainly in Ottawa and Montreal, purchased 384 copies. On 4 March 1870, Susanna Moodie wrote that her daughter had collected 280 names in those cities. The date “Mar 3d /70” appears at the top of one subscription page, and before that, 267 copies are listed. This document thus relates to the third, 88-page edition of Canadian Wild Flowers, which, despite the 1869 date on the title, was issued in 1870.

The Fisher collection also contains a small notebook (16.4 x 20 cm) titled “Canadian Wild Flowers. [rule] SUBSCRIPTION BOOK”, which FitzGibbon took with a copy of Canadian Wild Flowers on later recruiting forays. Subscribers, mainly in Ottawa and Montreal, purchased 384 copies. On 4 March 1870, Susanna Moodie wrote that her daughter had collected 280 names in those cities. The date “Mar 3d /70” appears at the top of one subscription page, and before that, 267 copies are listed. This document thus relates to the third, 88-page edition of Canadian Wild Flowers, which, despite the 1869 date on the title, was issued in 1870.

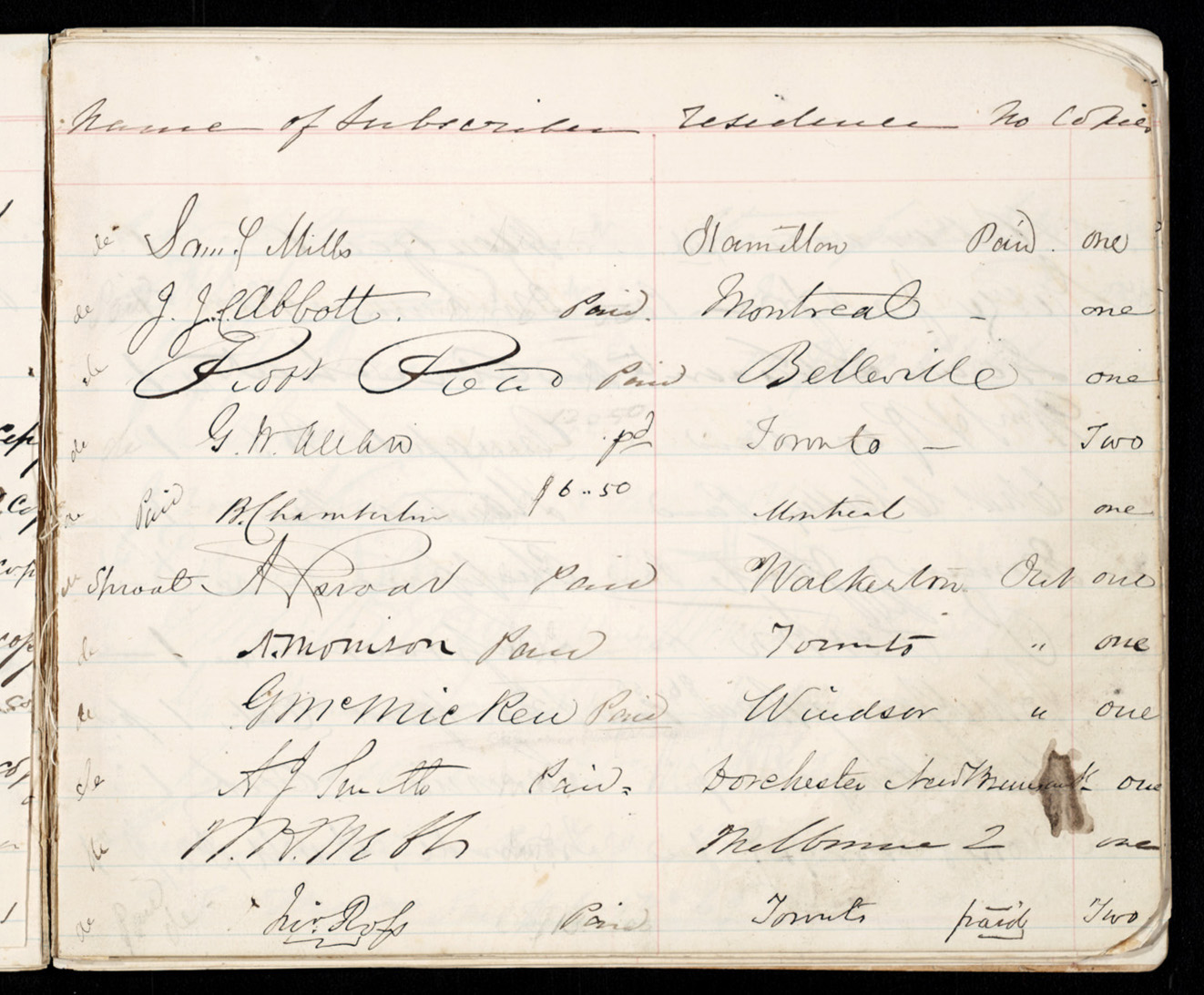

Once again, FitzGibbon staged the signatures brilliantly. The first page includes the names of eleven people who purchased between four and six copies each. The next page highlights Lady Adelaide Young, wife of the Governor General, whose name is followed by an order from the Library of Parliament. Other Ottawa figures include Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald for two new copies, scientist Sanford Fleming, lithographer George E. Desbarats, and W.C. Smillie of the British American Bank Note Company. Smillie’s business partner George Burland printed the 1869 lithographs for Canadian Wild Flowers. In Montreal, two copies went to publisher John Lovell, one to Robert Bell (a botanist with the Geological Survey of Canada), another to William Dawson (scientist and Principal of McGill College), and one to Member of Parliament Brown Chamberlin, owner of the Montreal Gazette, business partner of Burland and Smillie, and friend of the prime minister. FitzGibbon had found more than just subscribers. She married Brown Chamberlin on 14 June 1870 and moved to Ottawa, where domestic duties replaced her profitless work on Canadian Wild Flowers.

Once again, FitzGibbon staged the signatures brilliantly. The first page includes the names of eleven people who purchased between four and six copies each. The next page highlights Lady Adelaide Young, wife of the Governor General, whose name is followed by an order from the Library of Parliament. Other Ottawa figures include Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald for two new copies, scientist Sanford Fleming, lithographer George E. Desbarats, and W.C. Smillie of the British American Bank Note Company. Smillie’s business partner George Burland printed the 1869 lithographs for Canadian Wild Flowers. In Montreal, two copies went to publisher John Lovell, one to Robert Bell (a botanist with the Geological Survey of Canada), another to William Dawson (scientist and Principal of McGill College), and one to Member of Parliament Brown Chamberlin, owner of the Montreal Gazette, business partner of Burland and Smillie, and friend of the prime minister. FitzGibbon had found more than just subscribers. She married Brown Chamberlin on 14 June 1870 and moved to Ottawa, where domestic duties replaced her profitless work on Canadian Wild Flowers.

Brodie, Alexander H. “Subscription Publishing and the Booktrade of the Eighties: The Invasion of Ontario,” Studies in Canadian Literature 2.1 (1977). Available online at:

Agnes Dunbar (Moodie) Chamberlin Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto

!["Billy" Sunday : the man and his message, [1915]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000005.jpg?itok=5-pxPBhG)

!["Billy" Sunday : the man and his message, [1915]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000005-2.jpg?itok=ENb7n96W)