Donald Creighton, John Gray, and the Making of Macdonald

Donald Wright, University of New Brunswick

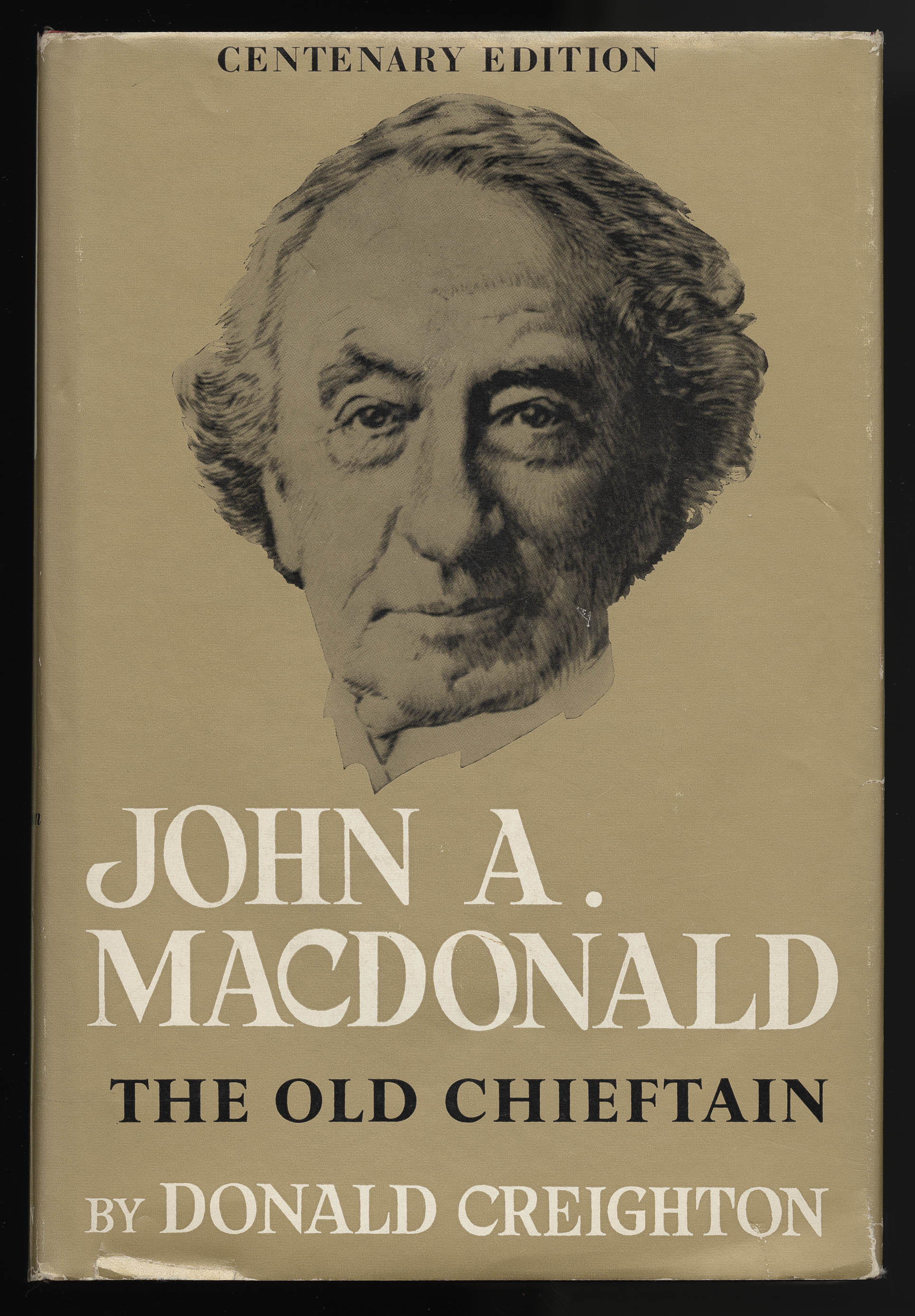

Donald Creighton was this country’s greatest historian. His first book, The Commercial Empire of the St. Lawrence (1937) established his reputation as an insightful thinker and gifted writer. One colleague called him the “hope of a new and better day” in Canadian historical writing. His two-volume biography of Sir John A. Macdonald—now recognized as one of the finest books ever written in Canada—confirmed his colleague’s expectations.

Publisher John Gray, meanwhile, had returned from active service in the Second World War in 1946 and not only resumed his career at Macmillan of Canada, but was also made general manager of the firm that June. A few months later, he met Creighton at an evening party. Creighton mentioned that he was at the beginning stages of a biography of Macdonald, although he had not the faintest idea what to do with the manuscript once it was finished: who in their right mind would publish a biography of a Canadian prime minister? Aware of Creighton’s capacities as writer, Gray invited him to lunch: “I coveted the privilege of being his publisher.” Twenty-four years later, Gray could still recall “the shared excitement of that first long talk.”

Although a subsidiary of Macmillan Company in London, England, Macmillan of Canada enjoyed considerable autonomy to select the books it wanted to publish. Still, it was a subsidiary. When Gray informed the London office of his desire to sign a contract with Creighton in 1948, Daniel Macmillan did not support his enthusiasm: do not, he said, “commit yourself.” There were already a number of biographies of Macdonald and Macmillan doubted very much if there was room for another. Gray agreed to wait and see, but added, “it would be a great pity if we lost this book.”

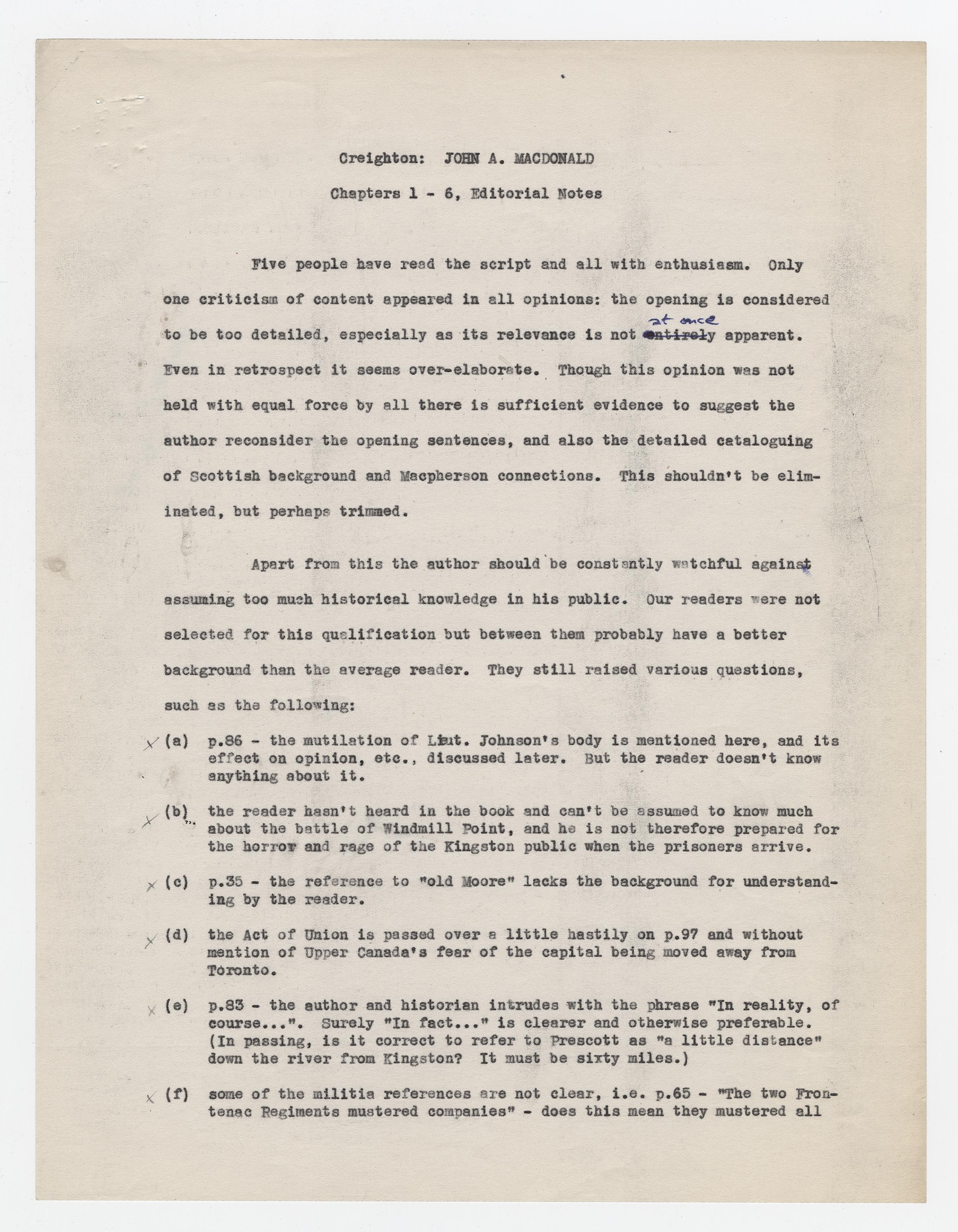

Unaware of Daniel Macmillan’s initial doubts, Creighton continued to work at an exhausting pace and, in the fall of 1951, he sent Gray the opening chapters to volume one which Gray, in turn, sent to a handful of readers. In January 1952, Gray prepared an editor’s report for Creighton. A prickly—even explosive—man, Creighton was furious. His wife, Luella Creighton (herself a published writer), recorded in her diary: “D.G. smoulderingly angry with his publisher over a few minor suggestions for revision. Proposes to wring John Gray’s neck.”

Unaware of Daniel Macmillan’s initial doubts, Creighton continued to work at an exhausting pace and, in the fall of 1951, he sent Gray the opening chapters to volume one which Gray, in turn, sent to a handful of readers. In January 1952, Gray prepared an editor’s report for Creighton. A prickly—even explosive—man, Creighton was furious. His wife, Luella Creighton (herself a published writer), recorded in her diary: “D.G. smoulderingly angry with his publisher over a few minor suggestions for revision. Proposes to wring John Gray’s neck.”

It is a good thing that Creighton did not see the readers’ reports. If he had, he may have carried out his threat to harm his publisher. “One seems at times to be reading a book by a Conservative rather than a book about one: it is slanted history,” complained one reader. “The author’s style is often verbose,” stated another. A third reader concurred: Creighton “fails to use one adjective exactly describing his noun but instead throws out two or even three ... It gives parts of his writing a verbose and even amateurish suggestion.” A fourth assessment was generally complimentary, but questioned the opening sentence. “‘In those days they came usually by boat.’ In what days? Who came by boat?”

Creighton agreed to make minor changes, but refused to make substantial revisions. “I gather that the real trouble with my biography is that it doesn’t correspond to what [the reader] remembers of his public school history. I am prepared to admit this: but it doesn’t interest me greatly. However, to pacify the gentleman and his kind, I have stuck in the kind of pontifical commonplaces which I suppose he likes.”

John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician was published in October 1952. In his review, the great British historian Max Beloff referred to Creighton as “one of the half-dozen best historians now writing anywhere in the English-speaking world.” Isaiah Berlin announced to his Oxford students that,  “on the strength of this one volume, I can say that I have been communing this past weekend with the greatest historical writer of our time.”

“on the strength of this one volume, I can say that I have been communing this past weekend with the greatest historical writer of our time.”

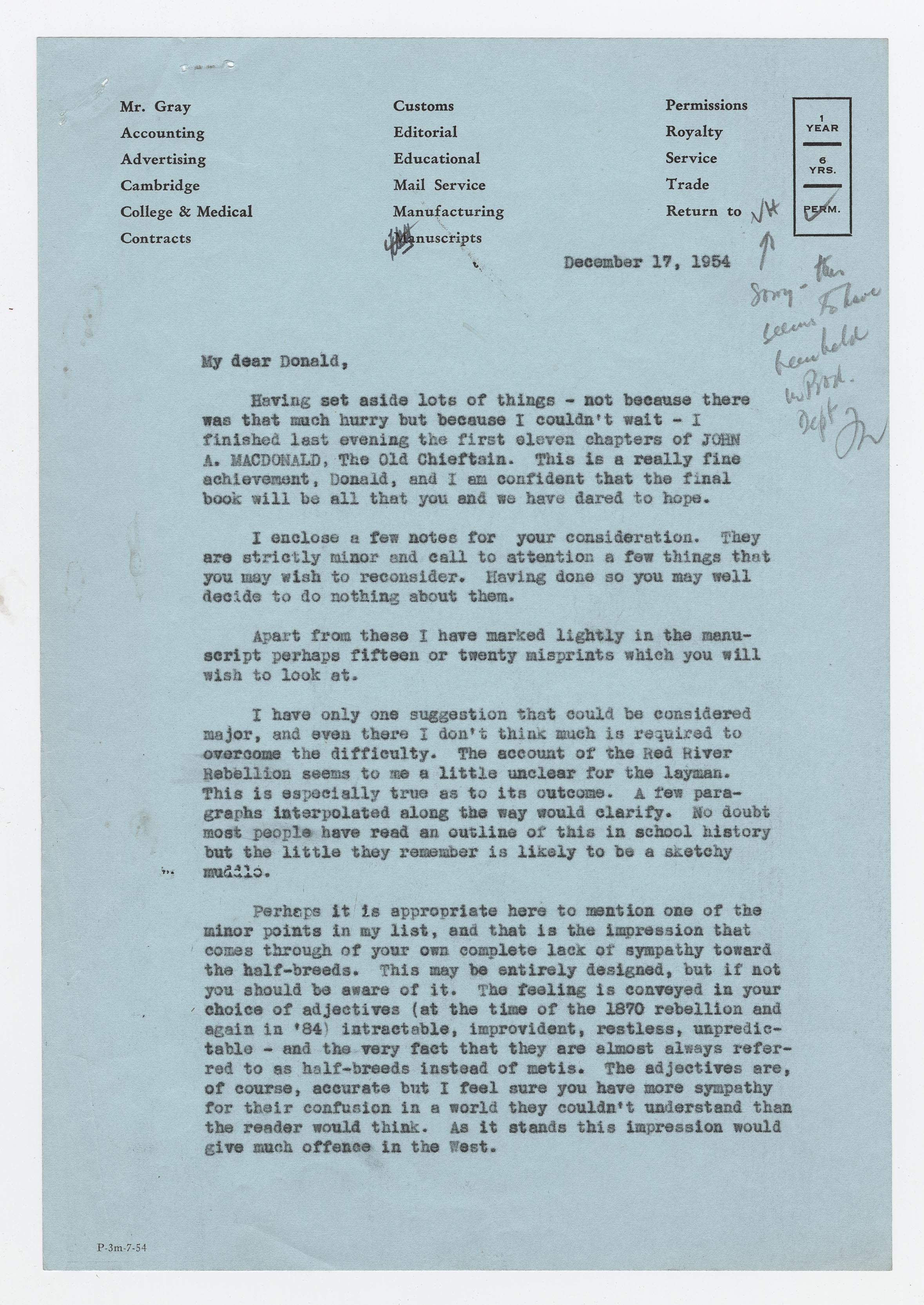

Two years later, Gray read the manuscript to volume two. He was naturally enthusiastic. But, gingerly, he commented on Creighton’s treatment of Louis Riel: “the impression that comes through [is] of your own complete lack of sympathy for the half-breeds.” It was an impression, moreover, that Gray worried would “give much offence in the West.” There is no record of Creighton’s response. Presumably, though, he did not think much of Gray’s  comment because he did not change his text. (Indeed, Creighton never understood Louis Riel’s re-incarnation as a hero. As he later told Ramsay Cook, “The best that can be said for Louis Riel—a strange recommendation for a hero—is that he ought to have been in the loony-bin!”)

comment because he did not change his text. (Indeed, Creighton never understood Louis Riel’s re-incarnation as a hero. As he later told Ramsay Cook, “The best that can be said for Louis Riel—a strange recommendation for a hero—is that he ought to have been in the loony-bin!”)

John A. Macdonald: The Old Chieftain was published in September 1955 and, like The Young Politician, was well received. Former prime minister Arthur Meighen told Creighton that it was “the finest biography any Canadian has produced.” But a Winnipeg teacher objected to what he called “the cavalier treatment of our own folk hero Riel.” Gray, it turns out, had  been right. Creighton responded that the people of Winnipeg in 1885 would be “astonished” to learn that Riel had become a folk hero.

been right. Creighton responded that the people of Winnipeg in 1885 would be “astonished” to learn that Riel had become a folk hero.

The Young Politician and The Old Chieftain earned Creighton two Governor General’s Awards. It also earned John Gray a reputation for being one of this country’s most important publishers.

Berger, Carl. The Writing of Canadian History: Aspects of English-Canadian Historical Writing since 1900. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976.

"Donald Creighton: Portrait of the Historian as an Artist." Edge: Research, Scholarship and Innovation at the University of Toronto. 2:2 (Fall 2000).

Available online at: http://www.research.utoronto.ca/edge/fall2000/content7.html

Wright, Donald. "Reflections on Donald Creighton and the Appeal of Biography." Journal of Historical Biography 1:1 (Spring 2007): 15-26.

Available online at: http://journals.ucfv.ca/jhb/Volume_1/Volume_1_Wright.pdf

Luella Creighton fonds, University of Waterloo

Donald Grant Creighton fonds, Library and Archives Canada

Macmillan Company of Canada fonds, McMaster University

![Press release from McClelland & Stewart, [15 September 1972], re Pierre Berton's The great railway illustrated](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00137.jpg?itok=GmULuoe2)

![Press release from McClelland & Stewart, [15 September 1972], re Pierre Berton's The great railway illustrated](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00137-2.jpg?itok=PhPs3u7i)

![Form letter announcement from Nelson Ball of Weed Flower Press, [1974], re cessation of operation](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP00145.jpg?itok=wZxrqSpb)