Job Printing and a Town Newspaper: The Collingwood Bulletin

Jenny Gilbert

The Collingwood Bulletin was founded in Collingwood, Ontario, in 1870 by David Robson who had moved his printing operation from Cobourg, on Lake Ontario. The Bulletin was the second newspaper in Collingwood, launched thirteen years after John Hogg had started the Enterprise. William Williams and J.G. Hand bought the Collingwood Bulletin from Robson in 1881. Four years later, Williams  took over proprietorship; his son, David, joined him in 1886, when he was seventeen. The elder Williams was responsible for the “job and business departments” while his son assumed editorial and journalistic duties. Like many printing offices of the day, the family business also trained apprentices, occasionally recruiting them through advertisements. By 1908, the newspaper was also employing girls to feed the job presses. Staff worked nine-hour days, which was common at the time. These and other details were recorded in a feature article, entitled “Journalism in Canada: The Bulletin” that appeared in the important trade journal, Canadian Printer and Publisher, in 1908.

took over proprietorship; his son, David, joined him in 1886, when he was seventeen. The elder Williams was responsible for the “job and business departments” while his son assumed editorial and journalistic duties. Like many printing offices of the day, the family business also trained apprentices, occasionally recruiting them through advertisements. By 1908, the newspaper was also employing girls to feed the job presses. Staff worked nine-hour days, which was common at the time. These and other details were recorded in a feature article, entitled “Journalism in Canada: The Bulletin” that appeared in the important trade journal, Canadian Printer and Publisher, in 1908.

Aside from printing local news and advertisements, the newspaper’s content was representative of country newspapers of its era and included serialized literature, sensational crime stories from around the globe, foreign news, and humorous tidbits.

Printing the weekly newspaper would not have taken much more than one day, and it made economic sense to keep the presses busy the rest of the time. Jobbing work was carried out frequently and quickly and did not usually demand large amounts of the print shop’s two main resources – labour and type. The newspaper advertised job printing services from the first issue on 12 July 1870, assuring readers of “perfect satisfaction,” “punctuality,” and “the latest and most approved patterns of type and presses.” Job printing also played a significant role in the growing community; Collingwood had many local shops, churches, and industries with a steady steam of printing requirements. The newspaper regularly advertised its services, often directly to customers whose businesses they were seeking: an

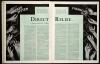

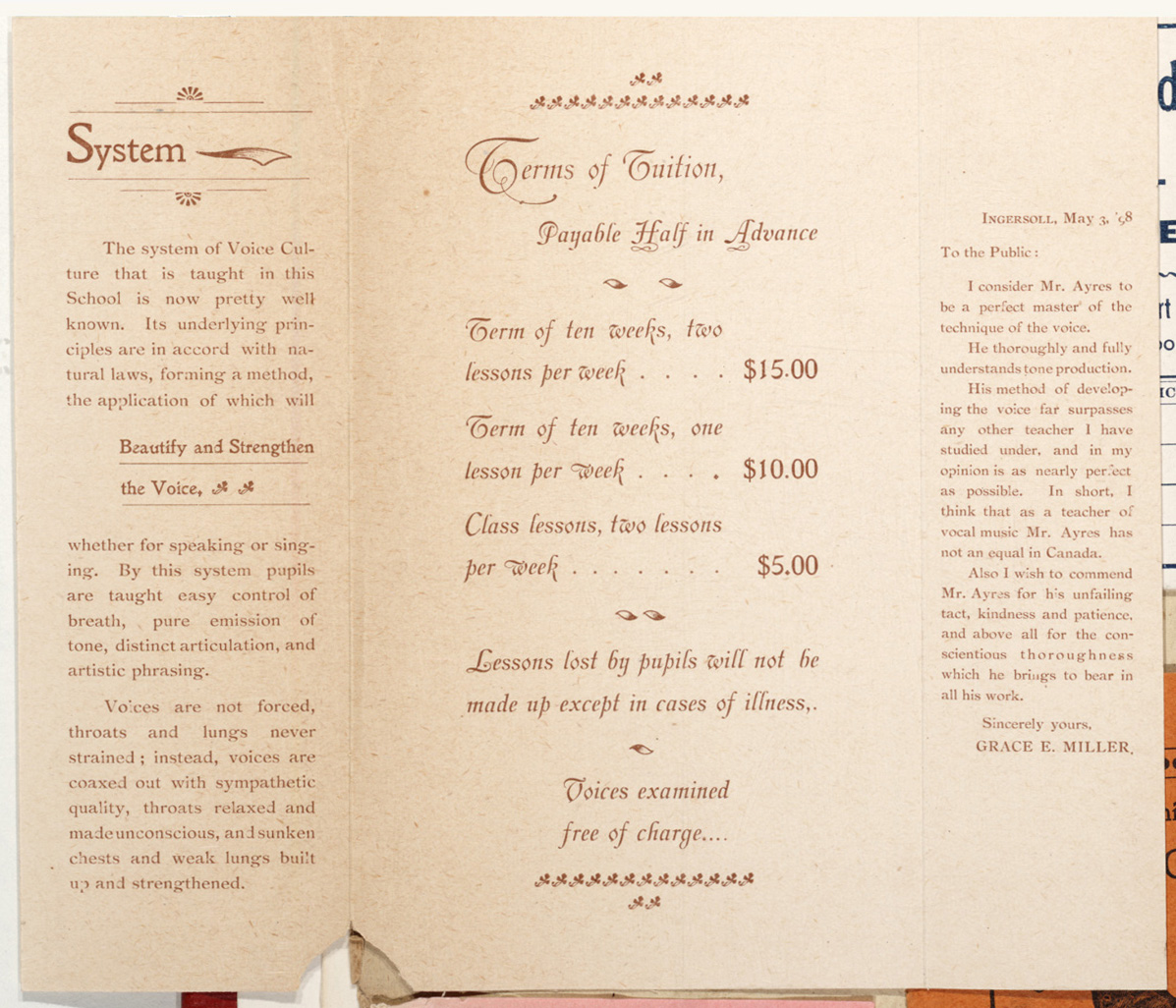

Printing the weekly newspaper would not have taken much more than one day, and it made economic sense to keep the presses busy the rest of the time. Jobbing work was carried out frequently and quickly and did not usually demand large amounts of the print shop’s two main resources – labour and type. The newspaper advertised job printing services from the first issue on 12 July 1870, assuring readers of “perfect satisfaction,” “punctuality,” and “the latest and most approved patterns of type and presses.” Job printing also played a significant role in the growing community; Collingwood had many local shops, churches, and industries with a steady steam of printing requirements. The newspaper regularly advertised its services, often directly to customers whose businesses they were seeking: an  ad on 8 December 1887 noted: “Sunday School committee’s [sic] wanting entertainment bills should consult their own interests and come to the Bulletin steam printing office for them.” Many job printers also canvassed the community for work; it is quite possible that David Williams would have done so too, as he advertised for canvassers to recruit new subscribers, in the 1893 issue of Canadian Printer & Publisher. The job printing done by the Bulletin included a range of items, which are discussed in more detail below.

ad on 8 December 1887 noted: “Sunday School committee’s [sic] wanting entertainment bills should consult their own interests and come to the Bulletin steam printing office for them.” Many job printers also canvassed the community for work; it is quite possible that David Williams would have done so too, as he advertised for canvassers to recruit new subscribers, in the 1893 issue of Canadian Printer & Publisher. The job printing done by the Bulletin included a range of items, which are discussed in more detail below.

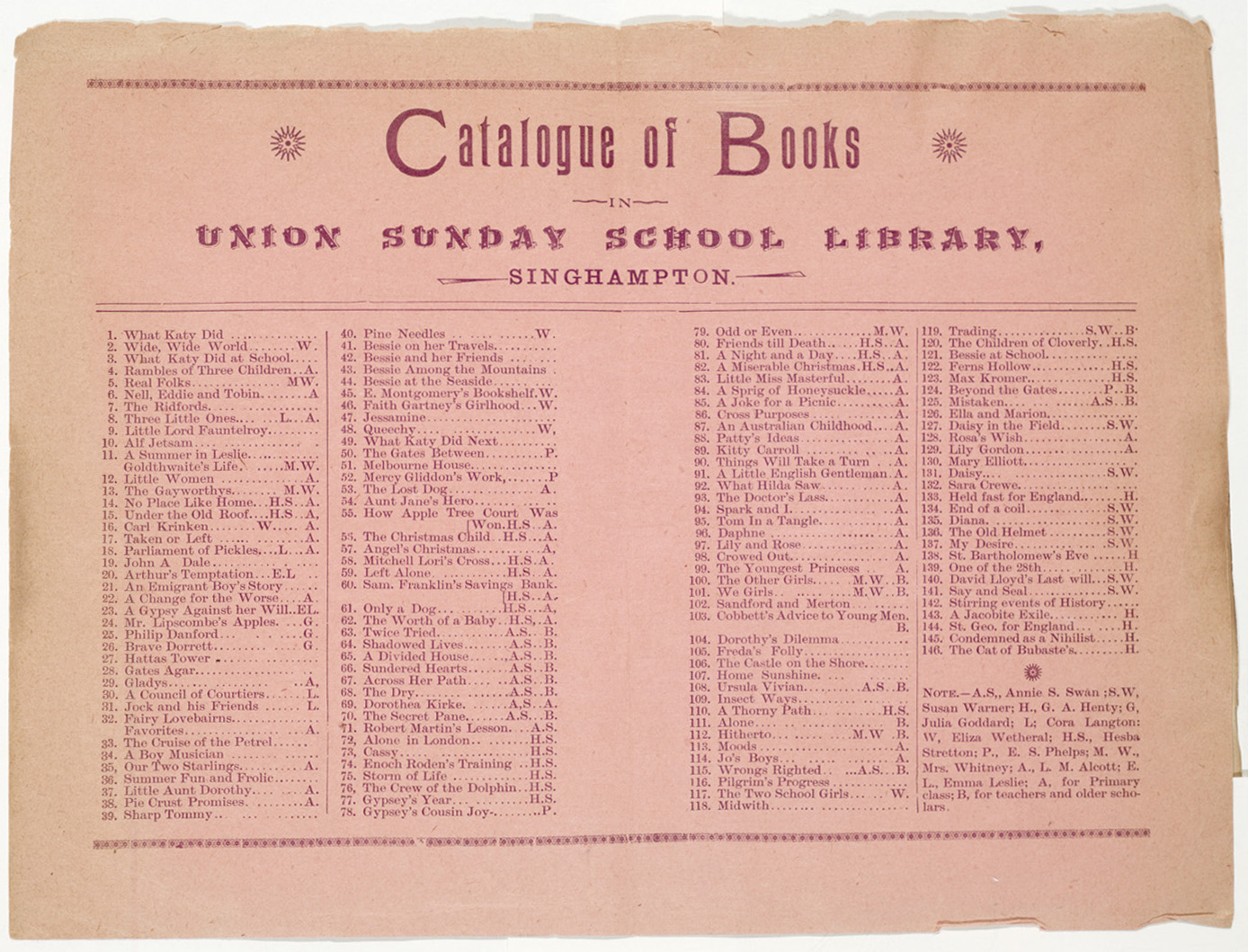

An item in the David William papers at the Collingwood Museum reveals how much the shop charged for some of this work. A receipt for job printing for the Masonic North Star Lodge No. 68, in 1871 and early 1872, when David Robson  owned the paper, shows that 500 printed envelopes could be had for $2.25, 200 circular letters were $2.75, 300 treasury receipts, bound, were $3.50, and 100 copies of bylaws, bound, were $26. The Bulletin also did work for the town council, which paid $54.85 for printing done in 1890, according to a notice in the 13 December 1888 edition of the paper.

owned the paper, shows that 500 printed envelopes could be had for $2.25, 200 circular letters were $2.75, 300 treasury receipts, bound, were $3.50, and 100 copies of bylaws, bound, were $26. The Bulletin also did work for the town council, which paid $54.85 for printing done in 1890, according to a notice in the 13 December 1888 edition of the paper.

In 1888 advertising rates were 10 cents per line for the first insertion and 3 cents for each subsequent insertion. A company placing a 4-line ad in the paper every week for a year, would bring in $6.24 for the year. Considering that subscriptions cost $1.50 or $1 a year paid in advance, job printing would have made up a substantial portion of the newspaper’s revenue, and perhaps rivaled revenue from advertising.

The nineteenth century in Canada witnessed a period of dramatic technological change in the printing industry, and the Bulletin office kept pace with the constant demand for new machinery. On 6 January 1887, the newspaper announced it had acquired a Campbell Power Printing Press, likely purchased in used condition from another printing shop or from a business which sold new and rebuilt presses. With so many technological advances, bigger shops sold or traded old presses for newer and faster models. The Bulletin itself was no exception, offering a Gordon job press for sale in 1910.

The nineteenth century in Canada witnessed a period of dramatic technological change in the printing industry, and the Bulletin office kept pace with the constant demand for new machinery. On 6 January 1887, the newspaper announced it had acquired a Campbell Power Printing Press, likely purchased in used condition from another printing shop or from a business which sold new and rebuilt presses. With so many technological advances, bigger shops sold or traded old presses for newer and faster models. The Bulletin itself was no exception, offering a Gordon job press for sale in 1910.

By the early twentieth century, the Bulletin office had amassed an impressive range of equipment that included monoline casting machines, a two-revolution Cottrell press, and three Gordon platen jobbing presses. Interestingly, in 1900 Williams sunk two wells next to his printing room to access natural gas, which powered the casting machines. By 1908, the presses were fully powered by two gasoline engines, according to the aforementioned 1908 feature article in Canadian Printer & Publisher.

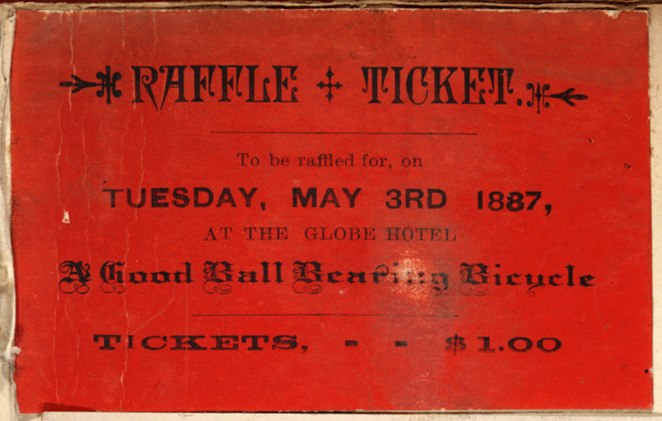

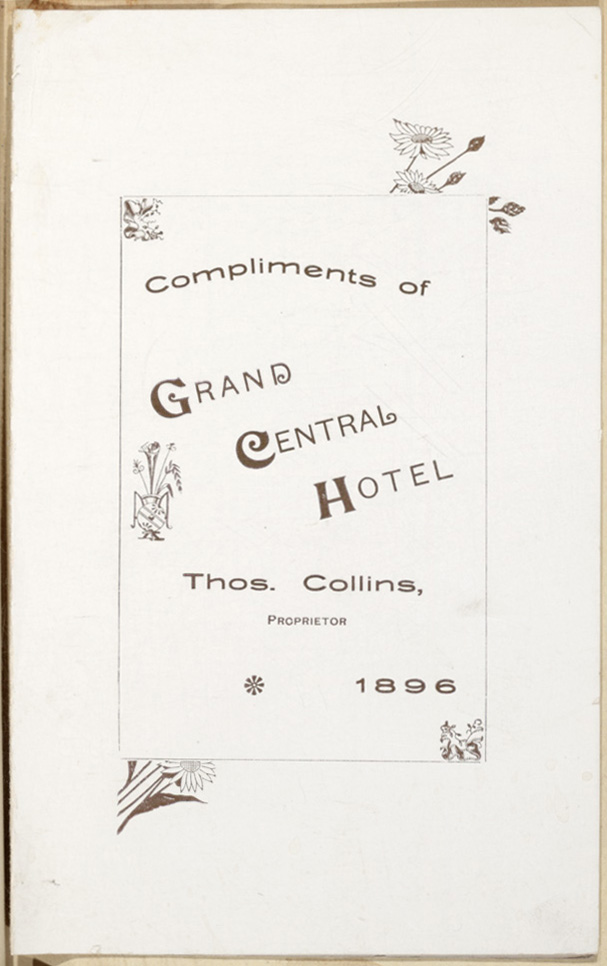

The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library has in its collections a scrapbook containing materials produced between 1886 and 1905 at the job printing office of the Bulletin. The scrapbook is an  amazing artifact, not only for its documentation of events, people, and businesses, but also as a record of the capabilities of the shop, indicating the range of coloured paper, paper stocks, and ink colours used. The printed materials are occasionally illustrated with engravings, but more frequently ornamental type was used to great effect. For the most part, black ink was used, though red, blue, purple, and brown also appear. Most commonly, the paper was white stock of varying quality. A cheaper pulp paper was used for letterhead and invoices, with better quality stock reserved for calling cards, business cards and invitations. For handbills, programmes, and other items, vibrant coloured paper was employed. Although the largest items are approximately 15” x 9.25” it is probable that the shop produced posters

amazing artifact, not only for its documentation of events, people, and businesses, but also as a record of the capabilities of the shop, indicating the range of coloured paper, paper stocks, and ink colours used. The printed materials are occasionally illustrated with engravings, but more frequently ornamental type was used to great effect. For the most part, black ink was used, though red, blue, purple, and brown also appear. Most commonly, the paper was white stock of varying quality. A cheaper pulp paper was used for letterhead and invoices, with better quality stock reserved for calling cards, business cards and invitations. For handbills, programmes, and other items, vibrant coloured paper was employed. Although the largest items are approximately 15” x 9.25” it is probable that the shop produced posters  and other larger-format items.

and other larger-format items.

The scrapbook is comprised of 192 pages containing a total of 562 items. The most common items are letterheads and envelopes, followed by printed invoices, and handbills advertising various shops and businesses. Other handbills advertise various entertainments, for which the shop also printed programmes and tickets. Legal documents including court summons and ballots are also present, as are shipping tags, circular letters, cheques, receipts, and Sunday School programmes.

The range of services, shops, and businesses represented in the scrapbook is also impressive. It includes butchers, bakeries, hotels, shipbuilders, milliners and dry goods stores, transportation companies, and numerous other enterprises. For local historians, print historians, and devotees of ephemera, the scrapbook is a fascinating record of job printing in a town newspaper.

When the Bulletin began publication in 1870, its political sympathies lay with the Liberal party, in contrast to the Conservative-leaning Collingwood Enterprise. In 1932, citing financial reasons, the two papers put aside their ideological differences and amalgamated to form the Enterprise-Bulletin, which is published in Collingwood to this day. The paper continued to advertise its job printing services well into the 1960s.

The author wishes to thank Professor Richard Landon, Director of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, for help and suggestions in the writing of this article.

The Bulletin. Collingwood. Microfilm: Archives of Ontario: N362.

“Journalism in Collingwood: The Bulletin.” Canadian Printer and Publisher: Toronto: MacLean Publishing Company, (1908, Vol. 17, Issue 7): 20. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library collection. Available online at: http://link.library.utoronto.ca/cpp/

Masonic North Star Lodge Receipt. David Williams Papers, Collingwood Museum, Accession Number X972. 994. 1.

“The Amalgamation.” Enterprise-Bulletin. Collingwood, Ontario. 7 July 1932. From the Collection of the Collingwood Museum, research folders.

Scrapbook of printer's proofs produced by the Bulletin job printing office, Collingwood, Ontario. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto, G-10 00842.

![A poetry reading by Dorothy Livesay [audio recording] / Dorothy Livesay](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01042.jpg?itok=dvoutGBK)