Marius Barbeau and the History of Anthropological and Folklore Publishing

Andrew Nurse, Mount Allison University

Barbeau was born in Ste-Marie-de-Beauce, Quebec, and grew up in a rural middle class family. As a child his mother and a local school provided his education before he left home to attend classical college and then Laval University in Quebec City. Initially, Barbeau imagined a quiet life for himself as a priest or lawyer, but he shifted to the newly emerging field of anthropology after winning a Rhodes Scholarship to study at Oxford. He also spent time at the Sorbonne under the direction of prominent French sociologist and intellectual Marcel Mauss before returning to Canada in 1910 to take up a  position with the newly established Anthropology Division of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC). Barbeau remained with the Anthropology Division – then, after a re-organization of government anthropology, with the National Museum - for the rest of his working life. In the latter part of his career, during and after the Second World War, he also taught on a part-time basis at the University of Ottawa and Laval University.

position with the newly established Anthropology Division of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC). Barbeau remained with the Anthropology Division – then, after a re-organization of government anthropology, with the National Museum - for the rest of his working life. In the latter part of his career, during and after the Second World War, he also taught on a part-time basis at the University of Ottawa and Laval University.

The creation of the Anthropology Division marked the beginning of a new chapter in the social sciences in Canada. From 1910 until after the broad growth of university-based social sciences after the Second World War, the Division constituted the centre of anthropological research, writing, and publication in Canada. This point was carefully explained to Barbeau by GSC head R.W. Brock. As a member of the Division, Barbeau was expected to transform research - particularly field research - into publications that served two functions: to preserve what was viewed as fast-vanishing traditional aboriginal cultures, and to provide cultural data to other anthropologists.

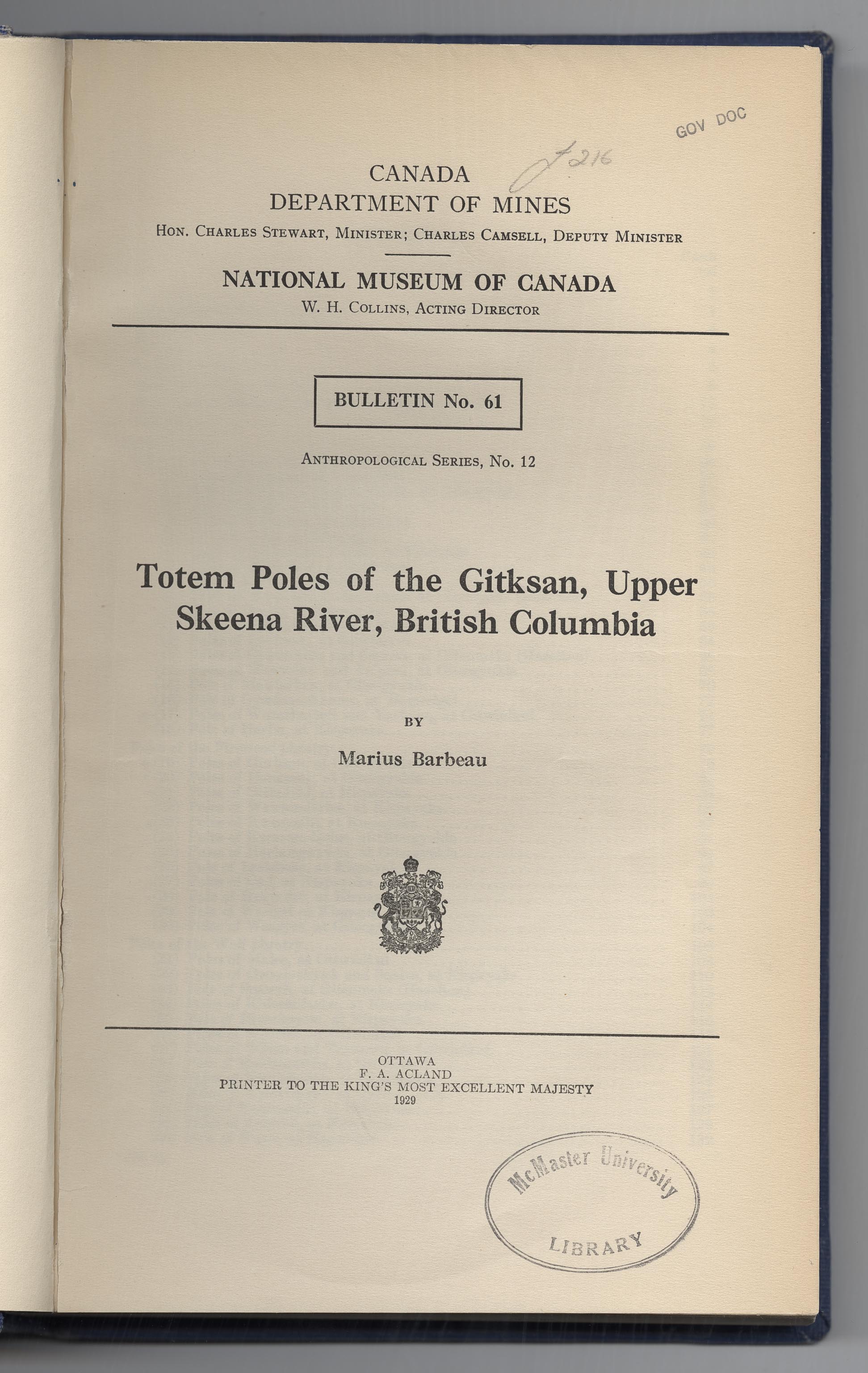

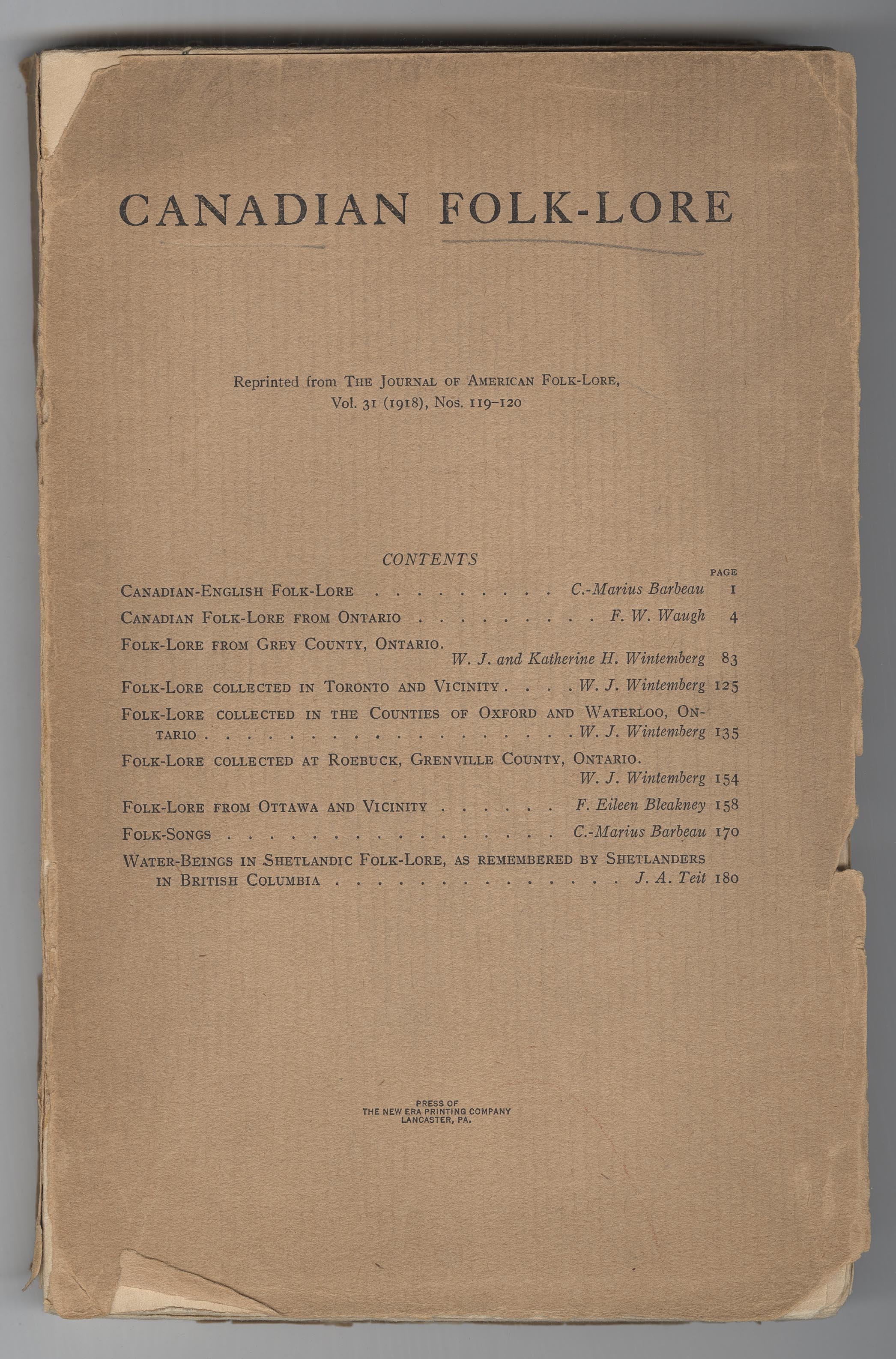

Canadian government anthropological publications appeared as special numbers of the established GSC publication series (which focused primarily on the geological, botanical, and biological sciences) and were tied to the  resources provided by the federal state through annual allocations and the expertise of Divisional staff who served in an informal peer review capacity. Anthropological publications could take a variety of forms, including interpretive essays or methodological works, but Barbeau’s writings tended to follow the model established by ethnologist Franz Boaz in the United States: compilations of primary documents with relatively brief scholarly explanations or descriptions. Through the GSC, Barbeau published works on Huron-Wyandot linguistics as well as French-Canadian folk material, First Nations oral traditions, and (most famously) images of Northwest Coast totem poles. Canadian and American scholarly or semi-scholarly periodicals, as well as Yale University Press, provided other venues for his work.

resources provided by the federal state through annual allocations and the expertise of Divisional staff who served in an informal peer review capacity. Anthropological publications could take a variety of forms, including interpretive essays or methodological works, but Barbeau’s writings tended to follow the model established by ethnologist Franz Boaz in the United States: compilations of primary documents with relatively brief scholarly explanations or descriptions. Through the GSC, Barbeau published works on Huron-Wyandot linguistics as well as French-Canadian folk material, First Nations oral traditions, and (most famously) images of Northwest Coast totem poles. Canadian and American scholarly or semi-scholarly periodicals, as well as Yale University Press, provided other venues for his work.

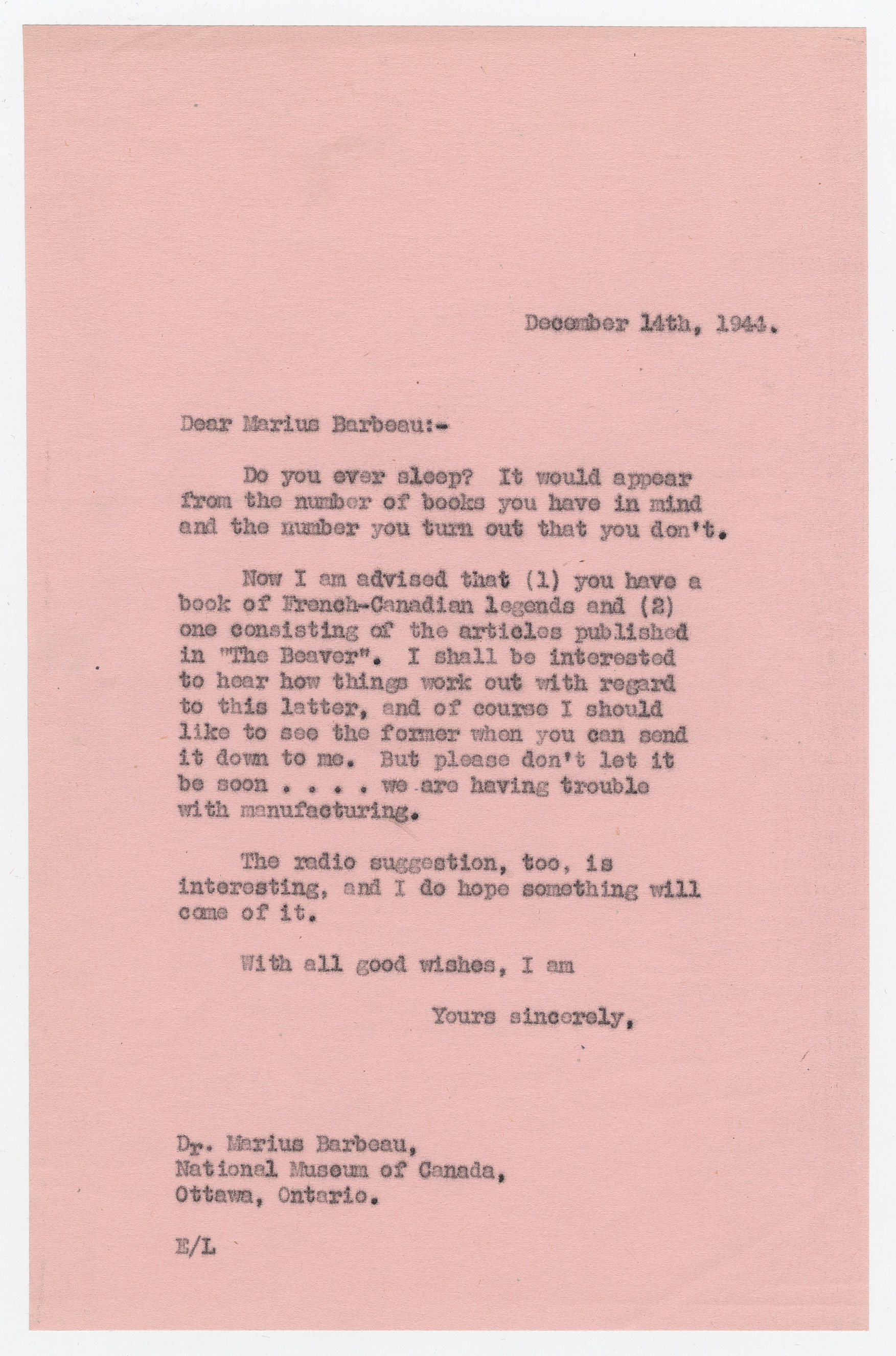

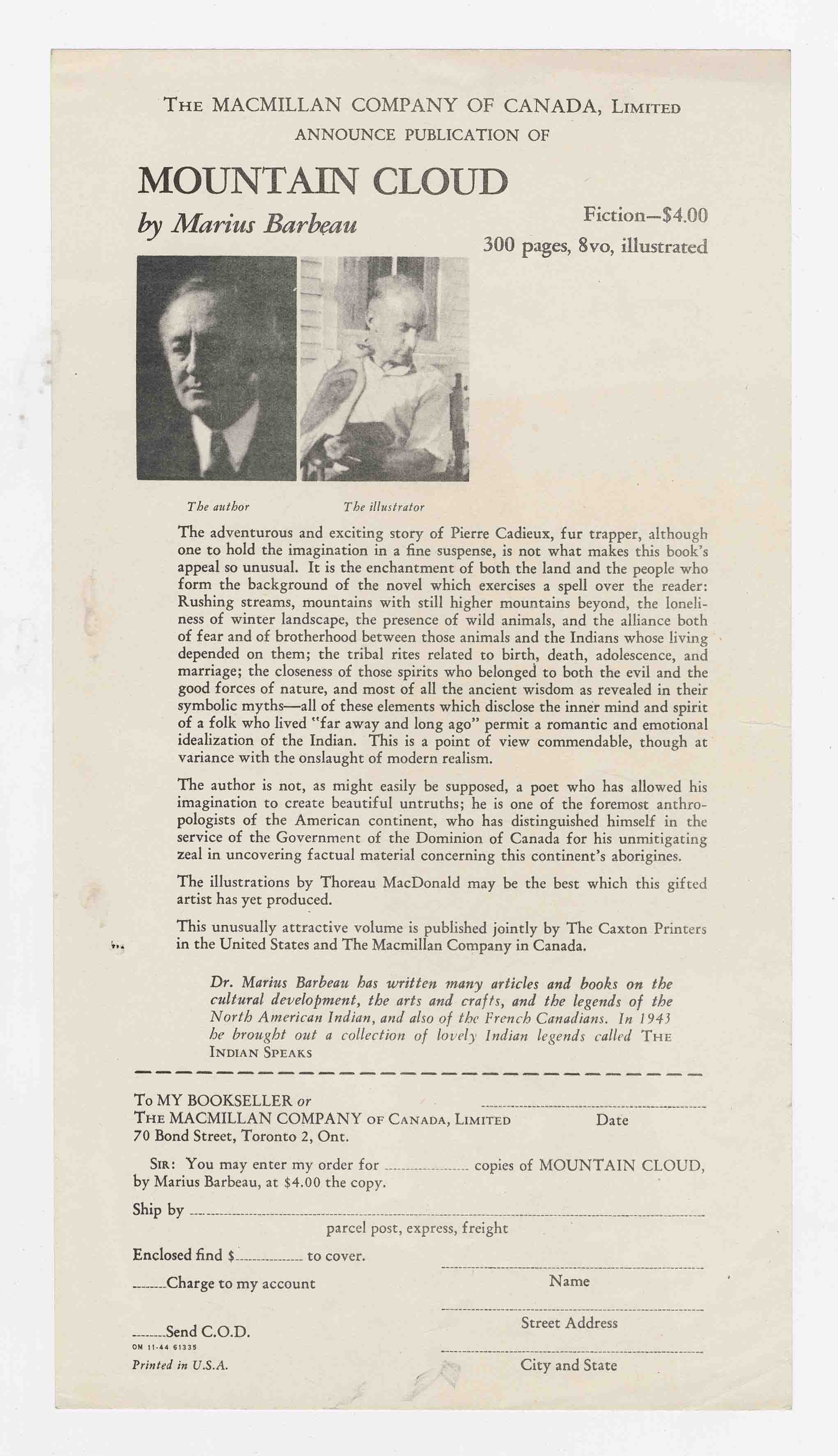

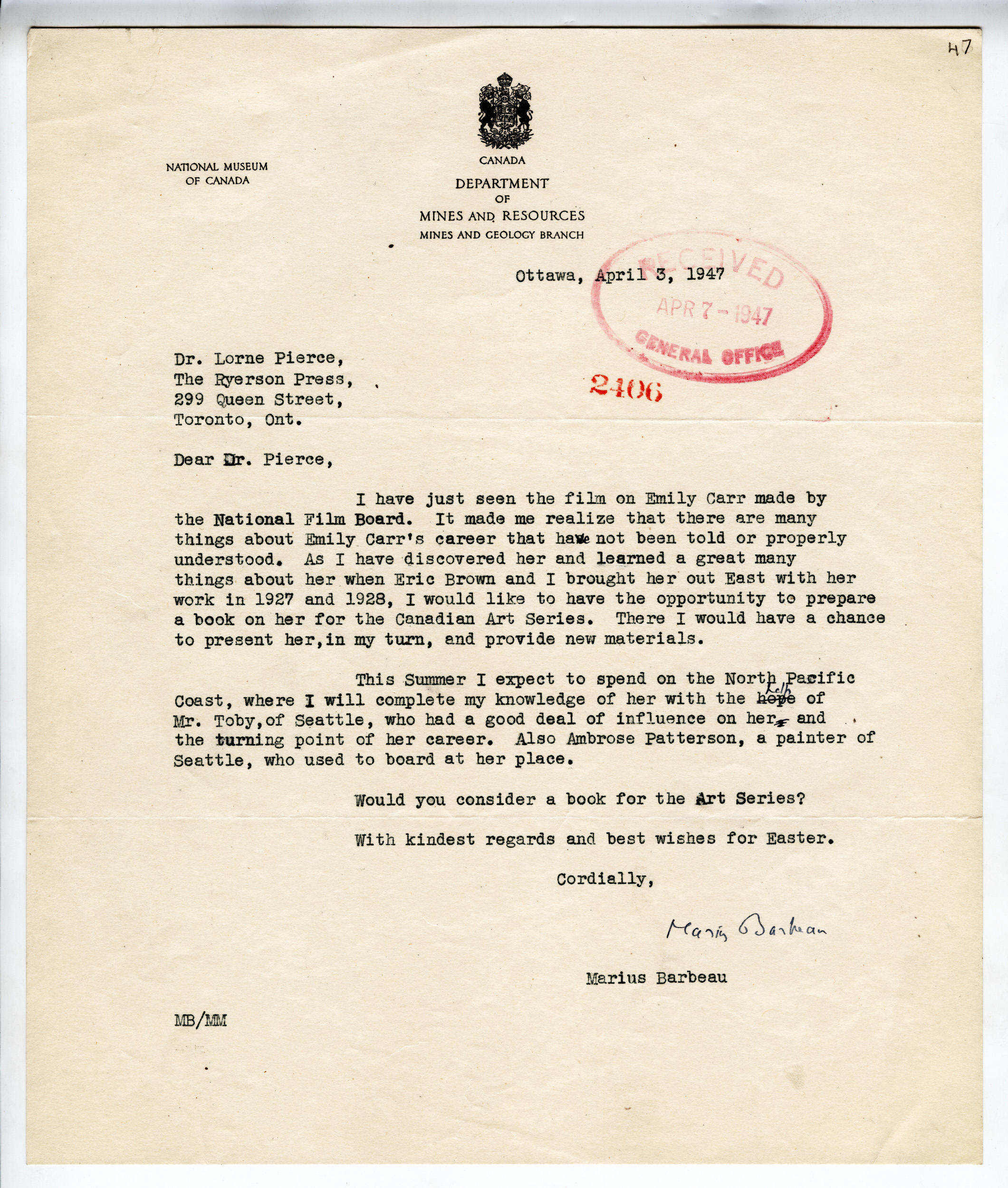

Like most Canadian anthropologists, Barbeau was interested in reaching a non-specialist audience. The connections he cultivated with non-scholarly publication venues were, however, unusual in their degree. The publisher with whom he worked most closely was Macmillan of Canada, and his correspondence with general editor Hugh Eayrs illustrates both the challenges and possibilities of popular publishing for social scientists like Barbeau. Exactly how the two men first met is not clear, but by the early 1920s they had begun what became an extensive correspondence. Barbeau’s initial interest lay in using northern British Columbian oral traditions as the basis for an “epic”  narrative that illustrated aboriginal cultural dynamics to a wider audience. He was also interested in publishing what he hoped would become an extended - perhaps definitive - series of traditional French-Canadian music collections. Both of these projects eventually made their way to press, but Barbeau’s interchange with Eayrs also served as a source for new publication initiatives that linked anthropology and folklore to the evolving tourist economy of twentieth-century Canada.

narrative that illustrated aboriginal cultural dynamics to a wider audience. He was also interested in publishing what he hoped would become an extended - perhaps definitive - series of traditional French-Canadian music collections. Both of these projects eventually made their way to press, but Barbeau’s interchange with Eayrs also served as a source for new publication initiatives that linked anthropology and folklore to the evolving tourist economy of twentieth-century Canada.

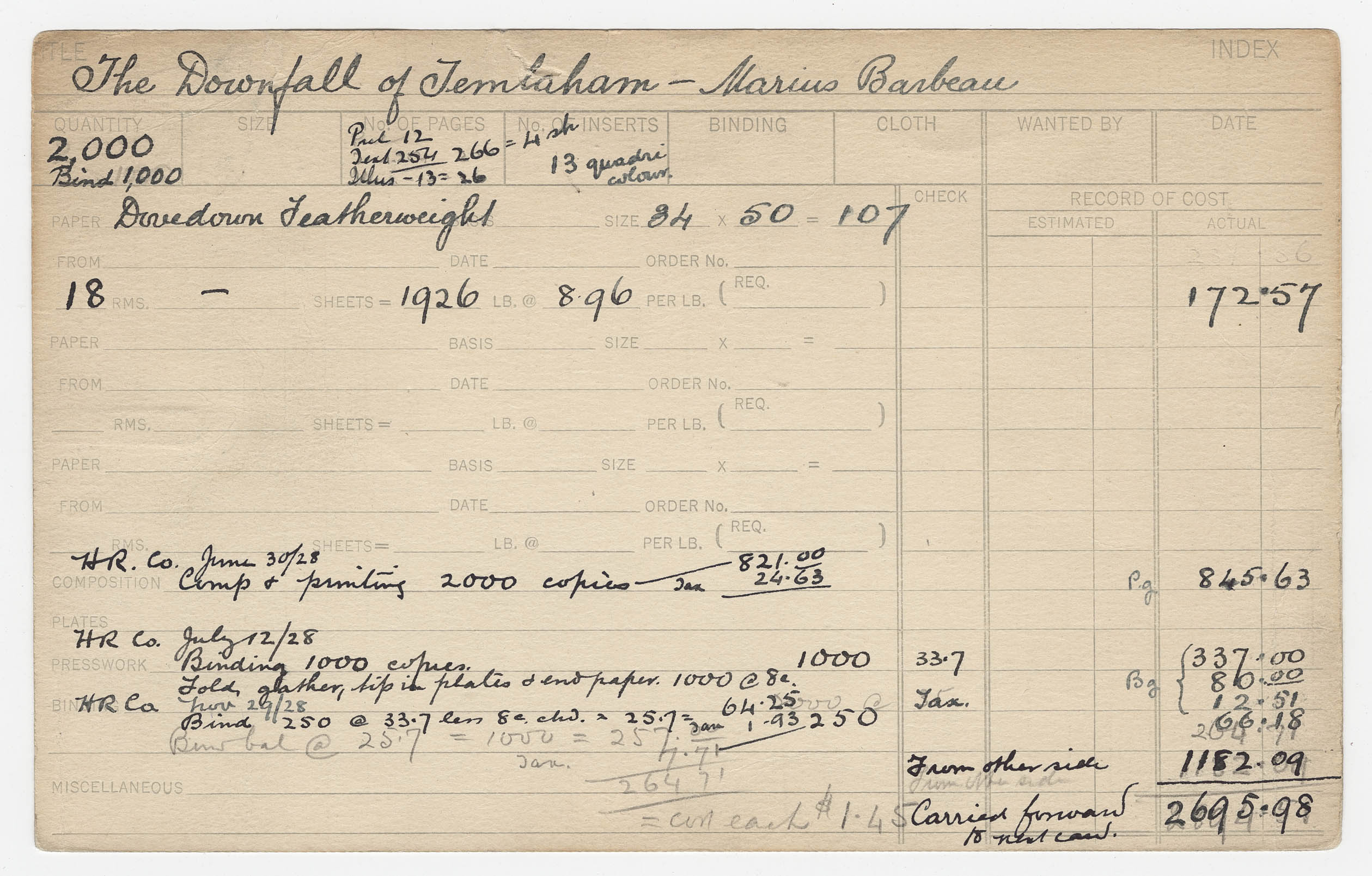

For Eayrs, Barbeau’s projects presented a problem. He liked them, but worried about their profitability. To address this issue, Eayrs and Barbeau looked for corporate support that could ease the cost of publication. Eayrs served as an  intermediary between Barbeau and company executives who looked to popular publications to boost tourist interest in resort hotels. For this reason both the Canadian Pacific Railways (CPR) and the Canadian Steamship Lines (CSL) supported Macmillan’s publication of Barbeau’s work. Two books appeared as a result of this business collaboration: The Kingdom of Saguenay (supported by the CSL) and Indian Days in the Canadian Rockies (supported by the CPR).

intermediary between Barbeau and company executives who looked to popular publications to boost tourist interest in resort hotels. For this reason both the Canadian Pacific Railways (CPR) and the Canadian Steamship Lines (CSL) supported Macmillan’s publication of Barbeau’s work. Two books appeared as a result of this business collaboration: The Kingdom of Saguenay (supported by the CSL) and Indian Days in the Canadian Rockies (supported by the CPR).

This arrangement subtly changed both the content and style of Barbeau’s writing. In the case of Indian Days, CPR officials told Macmillan that some of the original text needed to be revised to better reflect the character of local geography, that the original draft was too long for the target audience, and that some sections needed to be altered so as not to offend religious sensibilities. “No doubt,” the CPR’s chief publicity agent wrote Eayrs, “such controversies are alright for publications intended for a more scientific audience, but the whole idea of this publication is to create popular interest in the Indians.” The most significant overt change to Kingdom of the Saguenay was the title. Initially called In the Heart of the Laurentians, the book title was altered because CSL president Thomas Enderby was anxious to lure tourists year-round to the CSL

This arrangement subtly changed both the content and style of Barbeau’s writing. In the case of Indian Days, CPR officials told Macmillan that some of the original text needed to be revised to better reflect the character of local geography, that the original draft was too long for the target audience, and that some sections needed to be altered so as not to offend religious sensibilities. “No doubt,” the CPR’s chief publicity agent wrote Eayrs, “such controversies are alright for publications intended for a more scientific audience, but the whole idea of this publication is to create popular interest in the Indians.” The most significant overt change to Kingdom of the Saguenay was the title. Initially called In the Heart of the Laurentians, the book title was altered because CSL president Thomas Enderby was anxious to lure tourists year-round to the CSL  resort hotel at Tadoussac, and thought the original title conveyed too strong a sense of winter vacation and skiing. Kingdom of the Saguenay, he felt, evoked the geography and coastal lore of the river area. More significant changes were in tone, feel, and intent. In place of the scholarly monograph or compilation of primary texts, Barbeau constructed works that he, the publisher, and the sponsors felt would prove attractive to a middle class traveling public, perhaps convincing them to vacation in Banff or at the Manoir Richelieu in Quebec. Barbeau sought to evoke from his subject matter a sense of the exotic, the magical, and the unusual. In this manner Barbeau and Macmillan transferred scholarly pursuits to a broader reading public.

resort hotel at Tadoussac, and thought the original title conveyed too strong a sense of winter vacation and skiing. Kingdom of the Saguenay, he felt, evoked the geography and coastal lore of the river area. More significant changes were in tone, feel, and intent. In place of the scholarly monograph or compilation of primary texts, Barbeau constructed works that he, the publisher, and the sponsors felt would prove attractive to a middle class traveling public, perhaps convincing them to vacation in Banff or at the Manoir Richelieu in Quebec. Barbeau sought to evoke from his subject matter a sense of the exotic, the magical, and the unusual. In this manner Barbeau and Macmillan transferred scholarly pursuits to a broader reading public.

This story tells us a number of things about the history of social sciences publishing. First, it illustrates the centrality of publication to the early history of anthropology and folklore as disciplines in Canada. From the moment of their institutional origins, publication was central, and not incidental, to disciplinary practice. Second, the venues in which anthropologists and folklorists, like Barbeau, published were diverse. Studies into the history of anthropology have tended to focus on scholarly publishing to the exclusion of others. For Barbeau, at least, scholarly publishing did not take precedence over his other efforts to engage the public. A more detailed publishing history of the social sciences stands to add significantly to our understanding of disciplinary development and practice by looking at the ways in which differing publishing projects connected different publics to evolving fields of scholarship.

This story tells us a number of things about the history of social sciences publishing. First, it illustrates the centrality of publication to the early history of anthropology and folklore as disciplines in Canada. From the moment of their institutional origins, publication was central, and not incidental, to disciplinary practice. Second, the venues in which anthropologists and folklorists, like Barbeau, published were diverse. Studies into the history of anthropology have tended to focus on scholarly publishing to the exclusion of others. For Barbeau, at least, scholarly publishing did not take precedence over his other efforts to engage the public. A more detailed publishing history of the social sciences stands to add significantly to our understanding of disciplinary development and practice by looking at the ways in which differing publishing projects connected different publics to evolving fields of scholarship.

Finally, this story demonstrates again that the publishing process is not a neutral medium through which texts pass. In Barbeau’s case, publishing tied him to different publics but also became a focal point around which authorial, corporate, and cultural interests interacted. This interaction altered both the content and form of the final product, shifting its focus – in this case – from scholarship to tourist promotion. In assessing Canadian publishing history, attention to these types of subtle shifts serves to illuminate wider cultural processes. The issue is not simply that tourist promoters altered the wording of anthropological texts. What Barbeau’s story demonstrates is how publishing tied scholarly disciplines to the diverse processes that made modern Canadian culture.

Cove, John J. A Detailed Inventory of the Barbeau Northwest Coast Files. National Museum of Man Mercury Series, Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, Paper 54. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1985.

Creighton, Helen, et al. "Hommage à Marius Barbeau." Canadian Journal of Traditional Music 12 (1984). Available online: http://cjtm.icaap.org/content/12/v12art7.html

Landry, Renée and Denise Ménard. “Barbeau, Marius.” Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. Available online:

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=U1SEC8…

“Marius Barbeau: A Glimpse of Canadian Culture (1883-1969)." Canadian Museum of Civilization. Online exhibition:

http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/barbeau/index_e.shtml

Nurse, Andrew. “Marius Barbeau and the Methodology of Salvage Anthropology in Canada, 1911-51,” in Historicizing Canadian Anthropology, ed. Julia Harrison and Regna Darnell: 52-64. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2006.

Nurse, Andrew. “The Best Field for Tourist Sale of Books: Marius Barbeau, the Macmillan Company, and Folklore Publication in the 1930s.” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada, 36:1 (1997): 7-30.

Nurse, Andrew, Lynda Jessup and Gordon Smith, eds. Around and About Barbeau: Modeling Twentieth-Century Culture. National Museums of Canada Mercury Series – Cultural Studies 83. Gatineau: Museum of Civilization, 2008.

Turgeon, Laurier, Denys Delâge, and Réal Ouellet. "Marius Barbeau and the Folklore of Amerindiains." Canadian Journal of Folklore 17.1 (1995). Available online: http://www.celat.ulaval.ca/acef/171a.htm

Marius Barbeau fonds, Canadian Museum of Civilization

Edward Sapir fonds, Canadian Museum of Civilization

Fonds Marius Barbeau, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

Macmillan Company of Canada fonds, McMaster University

Lorne and Edith Pierce Collection. Marius Barbeau Sous-fonds, Queen’s University