“To renounce war ... and never support or sanction another”: The Peace Pledge Union, from 1934 to the 1960s

The dozen years following the First World War saw the general development of a cautious optimism that the preconditions of a just, stable and durable world peace were within reach. This hopeful mood was reflected in the Kellogg-Briand Pact, an agreement to renounce war as a method of resolving international disputes. Drafted by the American and French foreign ministers, the pact was eventually signed by sixty-two states.

With relations between the great powers seeming to move into a comparatively harmonious phase, the proponents of peace could dodge the thorny question of whether armed force might ever legitimately be employed in international affairs. The designation “pacifist” was embraced not only by men and women opposed on religious or ethical grounds to the use of violence in any circumstances, but also by liberal internationalists who valued the League of Nations as an instrument of war prevention. It could even be stretched to cover anybody who simply abhorred war or feared its recurrence, that is, to legions of people influenced by the “never again” mentality, a mindset fed by such classics of anti-war literature as All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and by grisly speculation about the likely horrors of another world war.

However, the international outlook grew more gloomy after the failure of the League of Nations to thwart Japanese aggression in Manchuria in 1931. This was followed, less than two years later, by the rise to power in Germany of a Nazi regime openly committed to overturning the post-war settlement in Europe. These developments set the world back on the road to war and disrupted the fragile unity between the disparate elements of the anti-war camp.

However, the international outlook grew more gloomy after the failure of the League of Nations to thwart Japanese aggression in Manchuria in 1931. This was followed, less than two years later, by the rise to power in Germany of a Nazi regime openly committed to overturning the post-war settlement in Europe. These developments set the world back on the road to war and disrupted the fragile unity between the disparate elements of the anti-war camp.

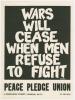

In October 1934 the Anglican cleric Canon Dick Sheppard circulated a famous peace letter to the British press in which he invited all who shared its pacifist sentiments to send him their signed pledges “to renounce war … and never support or sanction another”. Sheppard was challenging the proponents of a conventional approach to national security and defence based on military alliances and rearmament. He was also addressing those voices for peace who were coming to regard fascism, not war, as the more immediate threat to civilization and humanity and to favour “collective security” under the auspices of the League of Nations as the best way of deterring international aggression.

Acrimonious divisions opened up between former allies in a once broad and united peace front (as they did in mainstream politics between the defenders and critics of appeasement). The process of polarization was illustrated by Sheppard’s conversion of his peace pledge initiative into a full fledged political movement in May 1936. The activities of this Peace Pledge Union are documented in several holdings of papers in the William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster: the Russell Archives and the collections of Vera Brittain, George Catlin (Brittain’s husband) and John Barclay.

Acrimonious divisions opened up between former allies in a once broad and united peace front (as they did in mainstream politics between the defenders and critics of appeasement). The process of polarization was illustrated by Sheppard’s conversion of his peace pledge initiative into a full fledged political movement in May 1936. The activities of this Peace Pledge Union are documented in several holdings of papers in the William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster: the Russell Archives and the collections of Vera Brittain, George Catlin (Brittain’s husband) and John Barclay.

The continued emphasis of the PPU on simply “pledging” for peace was tactically astute, for it enabled the organization to avoid potentially damaging internal disagreements over which position to adopt on particular issues. Yet, while supporters of the PPU had concluded that no political outcome could be worse than another world war, other anti-war activists were concluding that sterner measures were required to constrain Hitler and Mussolini.

The tension between the anti-fascist and pacifist perspectives was sharpened by the Spanish Civil War. While supporters of the Republican side could draw a distinction between militaristic wars of conquest and the defence of democratic states and institutions, the orthodox pacifist outlook exemplified by the PPU was invigorated by the intensity of the military struggle in Spain and also by a foreboding that foreign intervention in it could trigger another catastrophic general war.

Bertrand Russell was one of several prominent public figures who signed the peace pledge and sat on the new organization’s executive--'perhaps the most intellectually distinguished committee ever assembled by a controversial British pressure group' (Ceadel, p. 223). In Which Way to Peace? (1936), Russell mounted a persuasive case for the pacifist remedies of unilateral disarmament by governments and non-resistance by individuals. Although an avid supporter of world government in principle, he was witheringly dismissive of the League of Nations in practice. He derided it as an alliance of victors from the last war and as toothless to boot. He also scorned the wishful thinking exhibited by votaries of the League who refused to accept that “collective security” could only be upheld by force in the last resort.

But Russell and the PPU had their critics as well. Pacifist calls for the imbalance of power between the “have” and “have not” nations to be redressed were seen as virtually indistinguishable from the British Government’s attempts to placate the dictators by a policy of appeasement. In a more polemical fashion, pacifism was equated with defeatism and treated as “objectively pro-fascist” by some of the PPU’s bitter enemies on the Marxist Left.

The seemingly rational arguments of Russell’s book made it extraordinarily useful to the PPU, as it provided compelling evidence that a pacifist position need not be the preserve of religious or ethical “enthusiasts”. Russell and other signatories of the peace pledge were attracted to pacifism in the 1930s as a method of war prevention that had not yet been tested and found wanting. When war, nevertheless, did occur, the political basis of their pacifism was undercut (although it should be noted that membership in the PPU peaked at some 136,000 during the period of the “phoney war” lasting from September 1939 until May 1940—when the Nazi onslaught on north-west Europe began in earnest). Russell, for example, rescinded his sponsorship of the PPU, and in a frank and public act of self-criticism, repudiated the pacifist arguments set forth in Which Way to Peace? as well as in many earlier speeches and newspaper articles.

Henceforth the PPU operated less as a “stop-the-war” organization and more as a refuge for uncompromising pacifists who wanted to maintain a personal witness for peace. Vera Brittain, another distinguished “sponsor” of the PPU, was among those who remained with the pacifist organization throughout the difficult war years. In deciding to join it in 1936 she had been impressed both by the force of Russell’s logic and by the powerful moral example set by the inspirational Canon Sheppard, whose death in October 1937 had been a terrible blow to British pacifism. In her peace work before the outbreak of war, Brittain had made a particular appeal to British women. In wartime she would become a relentless and controversial critic of the Allied policy of strategic area bombing of civilian targets in German cities.

Open to criticism for the naivité of its assessment of conditions inside Nazi-occupied Europe and for its ties to shady elements of the far Right who would have liked a compromise peace with Germany, the PPU nevertheless continued its peace work after 1945. During the Cold War the organization faced a quite different challenge—namely, how to avoid being tainted by association with Communist-aligned “peace” campaigners. Although active in the British anti-nuclear movement of the 1950s and 1960s, the by then venerable PPU performed a somewhat peripheral role in this struggle which was led by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Ceadel, Martin. Pacifism in Britain, 1914-1945 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980)