Claire Culhane: Canadian Peace Activist and Humanitarian

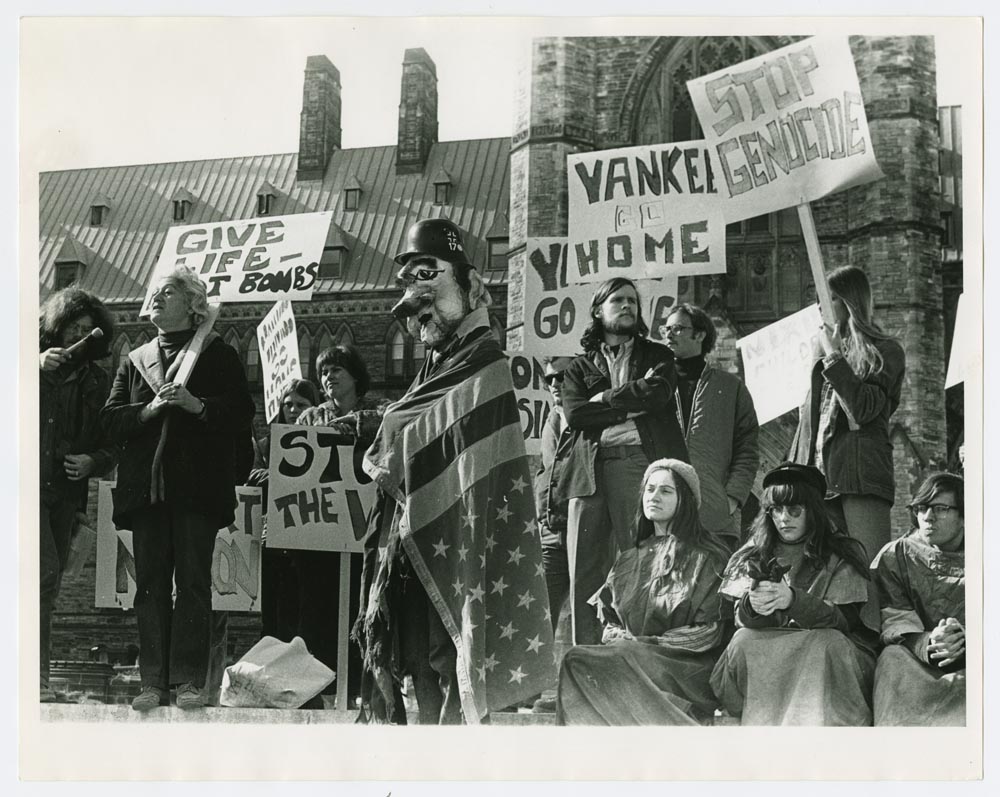

Peace activism in North America was utterly transformed in the 1960s and 1970s during the years of the Vietnam War. Along with widespread student protests and sit-ins, many self-dubbed “non-political” individuals held protest signs for the first time as they joined grass-roots movements to stop the war. In Canada, protesters also wanted the government to reveal the complete nature of their country’s role in the conflict. Why was Canada, known widely for its peacekeeping efforts, selling war materials to the U.S.? How could the government explain eyewitness reports of compromised Canadian relief efforts and collusion between aid workers and the U.S. military and CIA in Vietnam?

Claire Culhane was born Claire Eglin on 2 September 1918 in Montreal. The daughter of Russian-Jewish immigrant parents, she was married for a time to Gerry Culhane, with whom she had two daughters. By the late 1960s, she was already a seasoned social activist. She had been involved as an adolescent with the relief movement in Quebec during the Depression. As a young woman she had joined the Communist Party of Canada, participating in the youth movement striving to end the Spanish Civil War. These activities earned her the attention of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police: with some pride, she would state in later life that her RCMP file spanned nearly fifty years.

Culhane’s practical experience as a medical records librarian in Montreal, and her ongoing political interests, prompted her to take on a one-year government contract as an advisor and administrative assistant at a tuberculosis (TB) hospital established in Vietnam by the Canadian government. The facility was situated in Quang Ngai City, a provincial capital some 500 kilometres northeast of Saigon, not far what would become the war’s most insidious locale: My Lai. On 6 October 1967, Claire Culhane arrived in Quang Ngai to begin one of the most extraordinary and emotionally wrenching experiences of her life.

Culhane’s practical experience as a medical records librarian in Montreal, and her ongoing political interests, prompted her to take on a one-year government contract as an advisor and administrative assistant at a tuberculosis (TB) hospital established in Vietnam by the Canadian government. The facility was situated in Quang Ngai City, a provincial capital some 500 kilometres northeast of Saigon, not far what would become the war’s most insidious locale: My Lai. On 6 October 1967, Claire Culhane arrived in Quang Ngai to begin one of the most extraordinary and emotionally wrenching experiences of her life.

The city was in a deeply-embattled region, and she was awakened nightly by the sound of mortar shells and the eerie light of flares. Awaiting the arrival of essential machinery for the Canadian hospital, Culhane volunteered at the local provincial hospital, witnessing both the misery of Third World medical problems and horrific civilian injuries caused by traditional warfare and the new, sinister chemical weapon, napalm. On her first day she examined a mother and three small children, noting numbly in her diary: “infant had a hole in its back (size of an orange), 4 year old with tracer bullet scars across face from nostril to back of ear, mother [badly scarred,] result of previous cannon fire burns”. She would see, and help treat, far worse wounds during the following months.

Canadian House, where the aid workers lived, was often visited by American soldiers and officials, whose callous attitudes and actions, particularly towards civilians, sickened Culhane. A helicopter pilot joked about zooming in repeatedly on farmers to make them scurry until he could “kill them off”. Culhane also became increasingly aware of the conflicted relationship between her country’s aid effort and U.S. military activity. In Vietnam, Canadians relied on American infrastructure support (Culhane herself was flown from Saigon to Quang Ngai on an Air America plane, run by the CIA). She stated: “Although the assignment was designated as an independent, Canadian humanitarian project, it soon became evident that one could not function separate and apart from the war which was all about us”. She was also devastated to discover that the confidential records system she had set up for her hospital was repeatedly compromised by the head of the Canadian medical aid team, who liberally shared patient information with American embassy officials.

Dramatic events took place during the ferocious attacks of the Tet Offensive in February 1968. In spite of efforts to protect the hospital, it became a military target when South Vietnamese soldiers began using it as a base. The hospital had to be closed and Culhane campaigned to have patients moved to an empty ward in the provincial hospital. The hospital’s director refused the proposal. Broken-hearted and furious, Culhane and the staff readied the reluctant patients as best they could and sent them home, knowing that for many, ‘home’ no longer existed. After discovering evidence of further collaboration between some Canadian aid officials and the CIA, Culhane concluded that her presence and that of her colleagues was detrimental to the country they were supposedly assisting. She left Vietnam on 29 February 1968.

Dramatic events took place during the ferocious attacks of the Tet Offensive in February 1968. In spite of efforts to protect the hospital, it became a military target when South Vietnamese soldiers began using it as a base. The hospital had to be closed and Culhane campaigned to have patients moved to an empty ward in the provincial hospital. The hospital’s director refused the proposal. Broken-hearted and furious, Culhane and the staff readied the reluctant patients as best they could and sent them home, knowing that for many, ‘home’ no longer existed. After discovering evidence of further collaboration between some Canadian aid officials and the CIA, Culhane concluded that her presence and that of her colleagues was detrimental to the country they were supposedly assisting. She left Vietnam on 29 February 1968.

On her return to Canada Culhane filed an official report with the Canadian government, detailing events she had witnessed and decrying Canada’s complicity in the war. She called for immediate withdrawal of the Canadian team and she included recommendations on how to revitalize and improve the aid program. The Canadian government’s virtual suppression of the report, followed by policy revisions she felt were ineffective, infuriated and frustrated her.

Realizing the need for drastic action, on 30 September 1968 Culhane began a ten-day fast on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, supported by members of the Voice of Women organization, which had provided a strong backbone for the anti-war movement. She confronted numerous politicians, drew support from some elected members, and was finally granted a brief but ultimately fruitless meeting with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. The fast was widely-publicized and even received coverage in North Vietnam. A few months later she was invited to the international Stockholm Conference on Vietnam, and went to Paris during the Peace Talks to meet with officials. On her return to Canada she began a nationwide speaking tour.

In November 1969, the public learned of the March 1968 slaughter of hundreds of civilians at the hands of U.S. forces at My Lai. The attack took place less than two weeks after Culhane’s departure from Quang Ngai and it became a personal tragedy for Culhane; she learned that a dear hospital colleague had perished along with her four children. In December 1969 she was invited to participate in a Paris conference on war crimes. To her great joy, another invitee was a young woman Culhane had befriended in Vietnam.

Back in Canada, Culhane began another drastic action. On Christmas Eve 1969, with documentary filmmaker Mike Rubbo, she began a campaign she called “Enough/Assez”: enough horrors, enough vacillation, and enough complicity. The two spent the next nineteen days camped out in the cold, distributing hundreds of pamphlets and inviting the public to the site in Ottawa to discuss the war. Cameras captured some of the impassioned conversations. There is no doubt that the camp and Culhane’s continued efforts, including the 1972 publication of her book, Why is Canada in Vietnam?, helped galvanize the anti-war campaign and kept it in the forefront of Canadians’ minds.

In later years, the articulate and impassioned Culhane took up the cause of prison reform, and was appointed to the Citizens’ Advisory Committee for British Columbia Penitentiaries in 1976. She died in Vancouver in 1996, having inspired more than one generation of political activists.

Culhane, Claire. Why is Canada in Vietnam? The truth about our foreign aid (Toronto: NC Press, 1992)

Lowe, Mick. One Woman Army: the Life of Claire Culhane (Toronto: Macmillan Canada, 1972)