The Poetic Achievement of Contact Press (1952-1967)

David McKnight, University of Pennsylvania

In 1951, Louis Dudek returned to Montreal after an eight-year hiatus in New York City where he pursued a PhD at Columbia University. In Montreal Dudek re-established contact with Souster and Layton. At the time, Layton was also based in Montreal and Souster lived and worked in Toronto. The trio agreed that the state of Canadian poetry was in dire straits: commercial publishers showed little interest in experimental poetry, and there was a dearth of small presses.

After a lengthy correspondence, Souster announced in January 1952 that he intended to publish Contact, a mimeographed poetry magazine. Dudek and Layton were consigned to playing roles as editorial advisors. From its humble origins as a mimeo magazine, the Contact Press imprint took shape in April 1952 when Dudek, Layton, and Souster self-financed the publication of Cerberus, a selection of each of their work accompanied by a statement from each author.

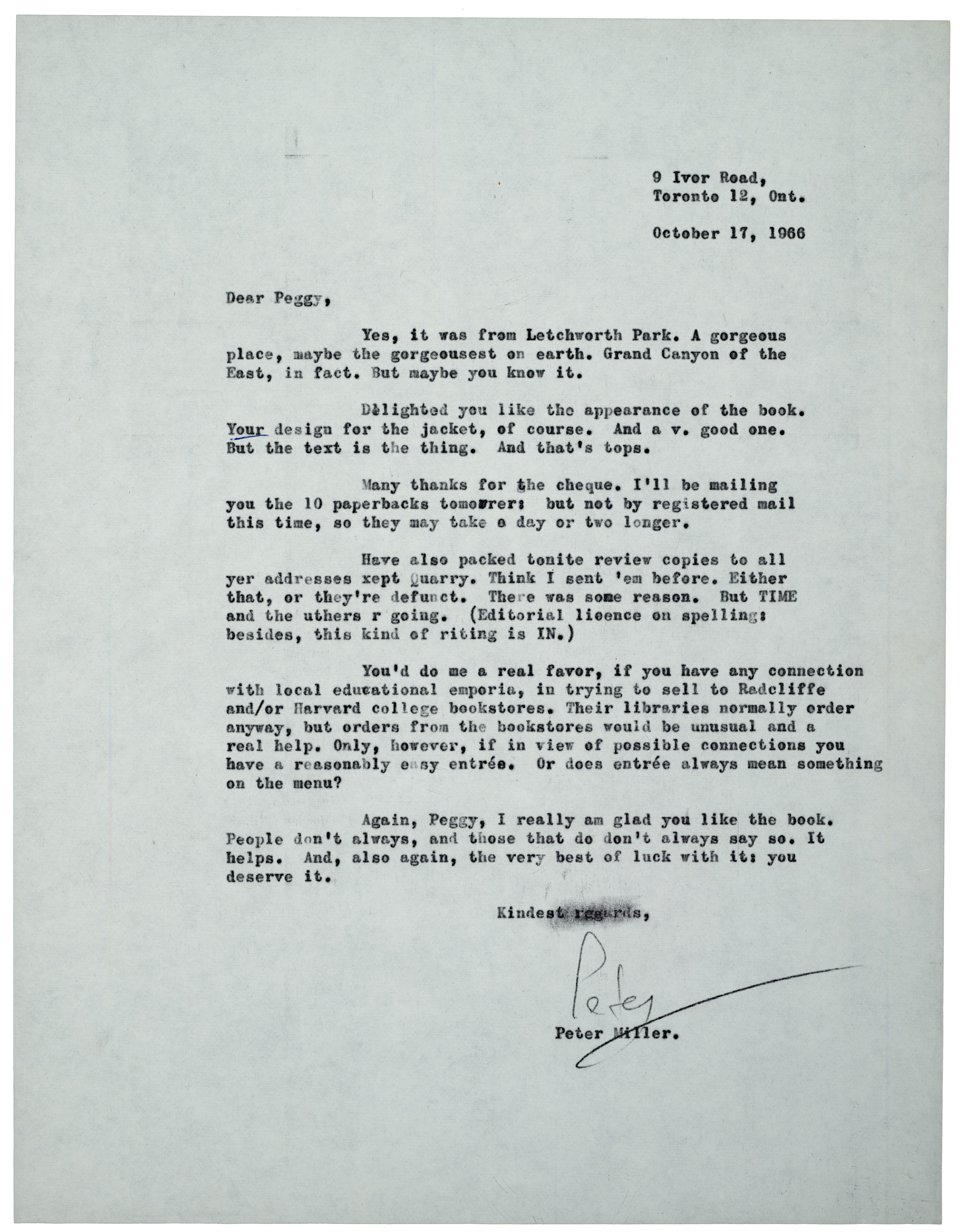

The editorial history of Contact can be divided into two periods: 1952 to 1959 and 1960 to 1967. During the first seven years, Dudek, Layton, and Souster used Contact as the imprint for publishing their own writings or individually initiating sub series, or agreeing (by majority vote) to  publish other works. The latter arrangement did not always work well. By 1959, Dudek and Layton’s professional and personal relationship had deteriorated and grown acrimonious. As a consequence Layton resigned from the Contact editorial board. After his resignation, Peter Miller joined Dudek and Souster in 1960 as a Contact editor. Miller, a Torontonian, was a poet and translator as well as Souster’s co-worker at one of the city’s banks who brought new capital and editorial verve to Contact. Dudek, who was involved in other publishing ventures, grew more detached from the press’ day-to-day operations. In 1966 Miller resigned as an editor, and Souster, alone, saw the final Contact title, New Wave Canada, through the press in 1967. He then handed off the small press publishing mantle to Coach House Press in Toronto.

publish other works. The latter arrangement did not always work well. By 1959, Dudek and Layton’s professional and personal relationship had deteriorated and grown acrimonious. As a consequence Layton resigned from the Contact editorial board. After his resignation, Peter Miller joined Dudek and Souster in 1960 as a Contact editor. Miller, a Torontonian, was a poet and translator as well as Souster’s co-worker at one of the city’s banks who brought new capital and editorial verve to Contact. Dudek, who was involved in other publishing ventures, grew more detached from the press’ day-to-day operations. In 1966 Miller resigned as an editor, and Souster, alone, saw the final Contact title, New Wave Canada, through the press in 1967. He then handed off the small press publishing mantle to Coach House Press in Toronto.

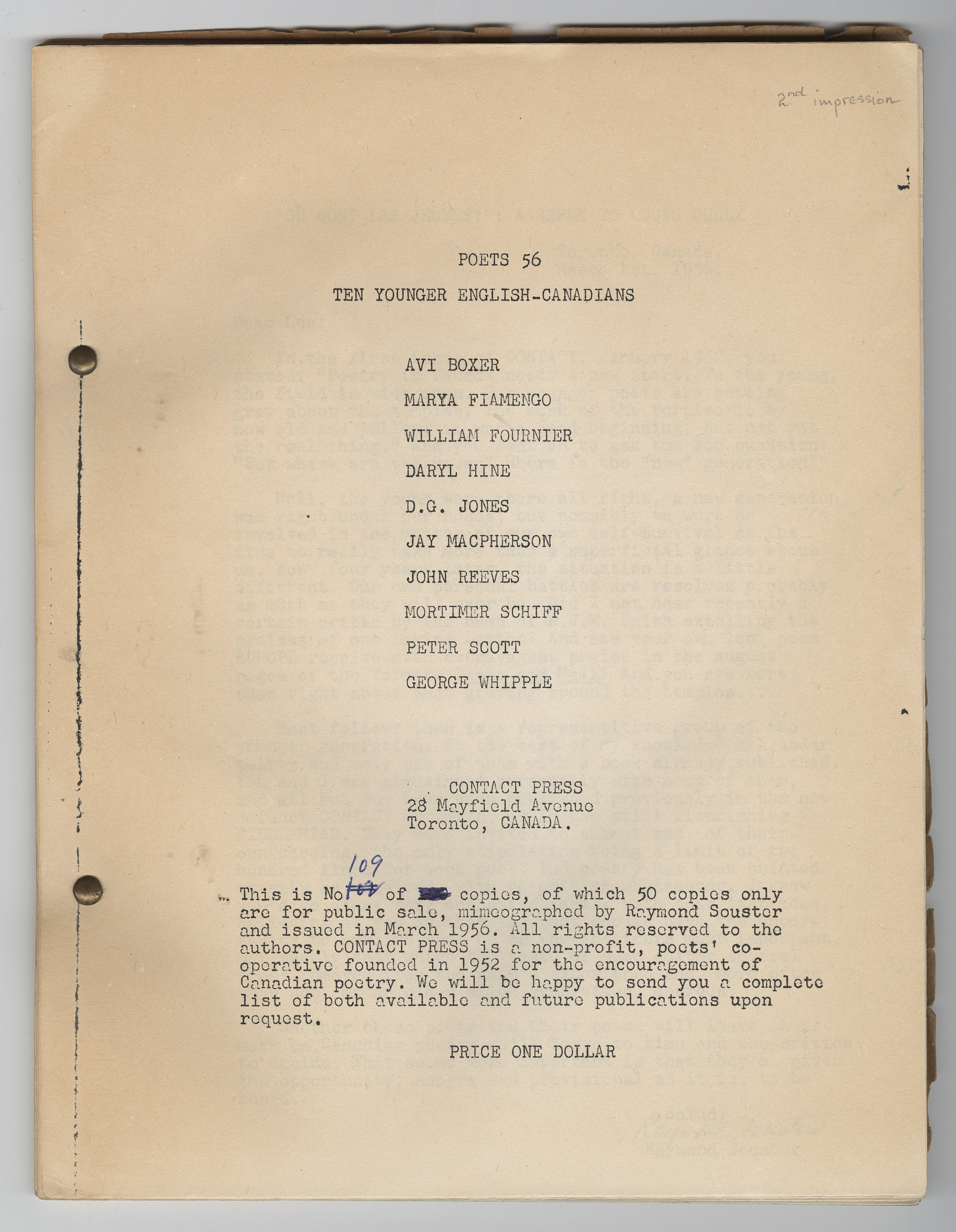

While Dudek, Layton, and Souster were publishing their own work during the 1950s, other interests and series emerged. In 1955, Souster, in collaboration with English expatriate poet, Gael Turnbull, produced a short-lived mimeograph chapbooks series which showcased four experimental Québécois poets. In 1956, Souster edited an anthology of younger poets, titled Poets 56, and in Montreal, Dudek launched the McGill Poetry Series which featured Leonard Cohen’s Let Us Compare Mythologies under the Contact imprint. Another early Contact title was Canadian Poems: 1850-1952,  an anthology edited by Dudek, for Layton, for use in Canadian schools. By 1954 there were 1500 copies of Canadian Poems in print.

an anthology edited by Dudek, for Layton, for use in Canadian schools. By 1954 there were 1500 copies of Canadian Poems in print.

Appearing in mimeograph format, paper editions, and occasionally in cloth, Contact Books were utilitarian in design and typography. During the 1950s, many Contact publications included minimalist, abstract-inspired cover designs by Betty Sutherland, Irving Layton’s first wife. After 1960, Contact editions were more uniform in design. A typical title was produced in a hardcover edition of 50 copies and a paper run of 200. The New Wave Canada anthology was certainly the press’ most elaborate production, in both a cloth and print edition with a limited cloth edition that included tipped-in original manuscript leaves replicated in a printed portfolio. The total number of copies was approximately 800. With Souster’s mimeographed titles produced in Toronto, Contact Books were printed either in Montreal or London, England.

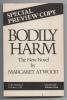

Contact authors included Phyllis Webb, Eli Mandel, Leonard Cohen, R.G. Everson, D.G. Jones, Alden Nowlan, Milton Acorn, Gwendolyn MacEwen, Frank Davey,  George Bowering, John Newlove, and Margaret Atwood. Translations also appeared featuring the work of Québécbois poets Roland Giguère, Anne Hébert, and Alain Grandbois, among others.

George Bowering, John Newlove, and Margaret Atwood. Translations also appeared featuring the work of Québécbois poets Roland Giguère, Anne Hébert, and Alain Grandbois, among others.

While print runs were not numerous, Contact books were distributed across Canada through an emerging underground poetry network which was publicized via advertisements and notices in little magazines and supported by direct sales from Souster’s home in Toronto. Receiving little government financial support or general recognition, Contact achieved many successes, most notably when Margaret Atwood’s The Circle Game received the Governor’s General Award for poetry in 1966.

In 1966, Raymond Souster remarked: “Contact appears to have formed a bridge over into [sic] the Fifties in which the modern Canadian poetical movement could begin its slow determined march” (Gnarowski, p. 2). Almost five decades later, it is evident that this “bridge” marshaled innumerable acolytes of the Canadian small press movement to follow the lead of Dudek, Layton, and Souster to create a number of vibrant self-publishing communities across Canada. This would have been impossible without the Contact Press.

Davey, Frank. Louis Dudek and Raymond Souster. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1980. Studies in Canadian Literature, 14.

Drumbolis, Nicky. A Modern Air. Toronto: Letters, 1991.

Gnarowski, Michael. Contact, 1952-1954: Being an Index to the Contents of Contact, a Little Magazine edited by Raymond Souster, Together with Notes on the History and the Background of the Periodical. Montreal: Delta Press, 1966.

Whiteman, Bruce. “Contact in Context: The Press in Its Time.” West Coast Line 25.2 (Fall 1991): 11-27.

Contact Press papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto

![The better part of valour; essays on Canadian diplomacy [by] John W. Holmes](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000027.jpg?itok=RejAwCFp)

![Postcard of Elevator foundation at Port Colborne, Ont. published by the Copp Clark Co. Limited-Toronto, [1906]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000032.jpg?itok=6kob4bg9)

![Postcard of Elevator foundation at Port Colborne, Ont. published by the Copp Clark Co. Limited-Toronto, [1906]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP000032-2.jpg?itok=7LEn-mlC)