Stan Bevington: The Making of a Master Printer with Audio Interview

Sarah Hipworth, Toronto

Stan Bevington, founding publisher of Coach House Press, was born in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1943, the son of teachers [01]. His father also worked as a carpenter and, in 1946, built the family house that Bevington would grow up in [02]. As a child he had toys that encouraged handcraft, [03] and he took classes at the Edmonton Art Gallery.

In high school, through helping to build a theatrical set, he met a professional artist and silkscreen printer to whom he became apprenticed [04]. Bevington subsequently entered model house-building contests and began a second apprenticeship with an architect from whom he learned drafting skills and who also had a dark room [05]. Bevington silkscreened posters for school events and designed and edited the school yearbook, in which capacity he saw his first linotype machine on a visit to the printer [06].

Throughout high school, summer jobs enhanced his skills and taught him professionalism. One summer, he worked at a silkscreen shop and at a print shop where he encountered, for the first time, drawers of lead type [07]. The following year, he worked at a print shop in Edson, Alberta, [08]. After Grade twelve, a series of positions included a stint at the Edmonton Journal, as well as working on an airport runway in Fort Smith, Northwest Territories [09], at a corrugated box factory [10], and at a small country print shop in Fairview Peace River, Alberta [11].

In 1962, determined to become an architect, Bevington left Edmonton for Toronto to begin a fine arts degree at the University of Toronto [12]. He dropped out of the program that February and worked at a print shop in Scarborough [13] and then at a rubber stamp factory in downtown Toronto [14], all the while honing his skills as a printer. In the fall of 1963, he enrolled at the Ontario College of Art [15].

The following summer he saw the Canadian government’s design proposal for a new Canadian flag, and set up a studio in his basement, silkscreened the flags, and sold them on the streets of Yorkville [16], an area of downtown Toronto famous at the time for its counterculture. Bevington had the opportunity to buy his first printing press, and moved into a studio at Dundas and Bathurst (the first Coach House location) [17], and launched what became a burgeoning printing business [18].

The following summer he saw the Canadian government’s design proposal for a new Canadian flag, and set up a studio in his basement, silkscreened the flags, and sold them on the streets of Yorkville [16], an area of downtown Toronto famous at the time for its counterculture. Bevington had the opportunity to buy his first printing press, and moved into a studio at Dundas and Bathurst (the first Coach House location) [17], and launched what became a burgeoning printing business [18].

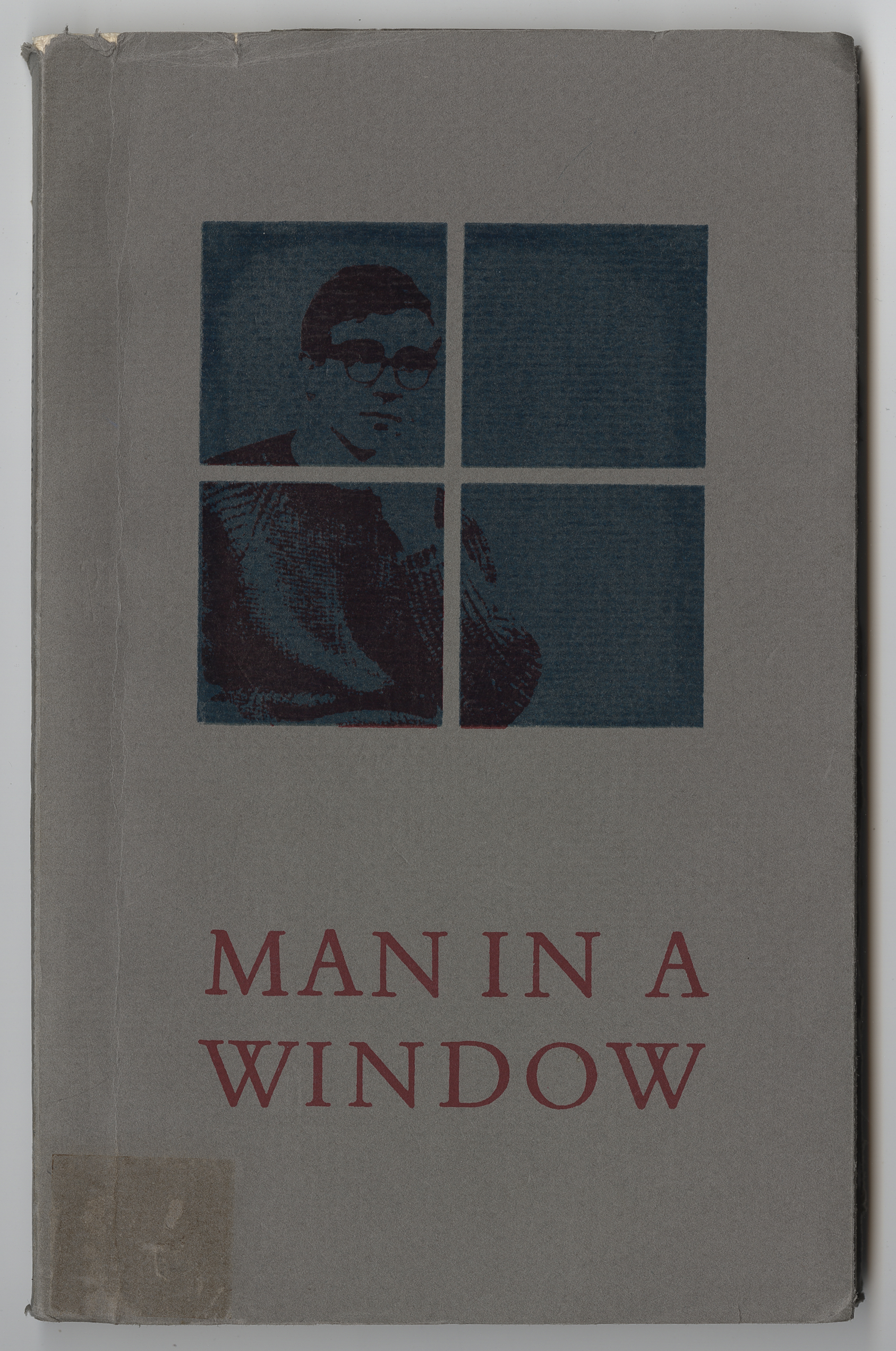

Freelance work aside, his “really official good job” as a printer was to make posters for the Toronto Public Library, which in turn led to work for the Isaacs Gallery [19]. He exchanged services with Albert Offset, a trade printery down the street, which allowed him to expand his customer base [20]. In February 1965, Bevington printed  Man in a Window by Wayne Clifford, the first official Coach House book [21]. Other books soon followed [22]. As the business grew, so too did the number of presses at Coach House [23].

Man in a Window by Wayne Clifford, the first official Coach House book [21]. Other books soon followed [22]. As the business grew, so too did the number of presses at Coach House [23].

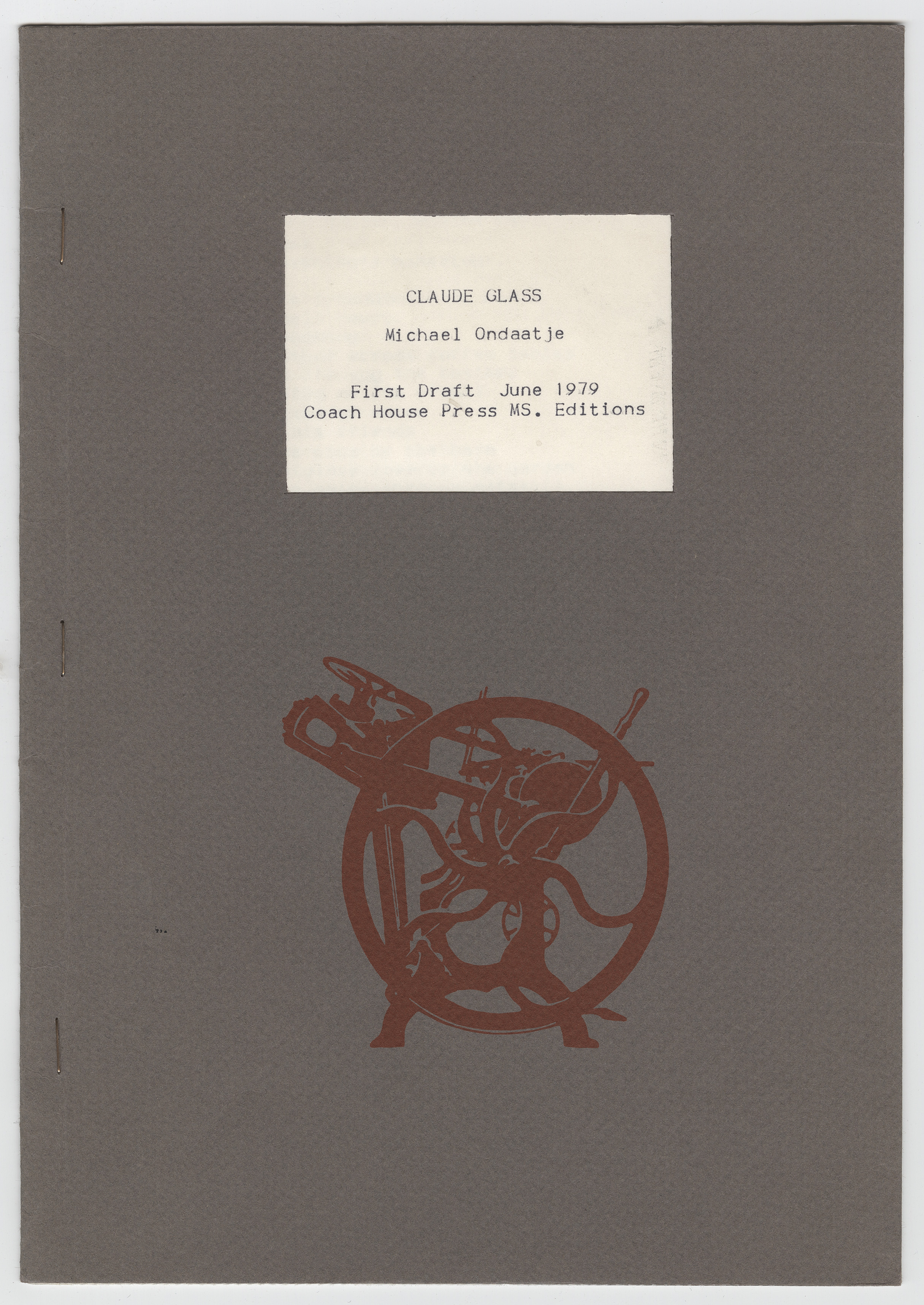

One of the features of the print shops Bevington worked for in small-town Alberta was their combined community centre/workplace environment. Under Bevington’s direction, Coach House fostered a similar (although more radical, collaborative, and artistic) atmosphere [24]. The Coach House had visits from touring and local poets and artists. Through this network, Bevington met many eminent cultural figures, including Victor Coleman [25] (an influential writer and editor who would become Coach House’s senior editor) and Michael Ondaatje, whose first book, Dainty Monsters, Coach House printed in 1967 [26].

When the lease expired at Bathurst and Dundas, poet and editor Dennis Lee suggested that Bevington join Rochdale College, the free university for which Bevington had printed avant-garde ephemera [27]. As the new Rochdale building was not complete, Coach House equipment was moved into a double garage on a nearby laneway off Huron Street [28]. They grew to like the location and decided to stay: Coach House Press remains there to this day.

When the lease expired at Bathurst and Dundas, poet and editor Dennis Lee suggested that Bevington join Rochdale College, the free university for which Bevington had printed avant-garde ephemera [27]. As the new Rochdale building was not complete, Coach House equipment was moved into a double garage on a nearby laneway off Huron Street [28]. They grew to like the location and decided to stay: Coach House Press remains there to this day.

For the first year or so at the new location, Coach House operated much as it did before, printing posters, books, and small literary magazines. Eventually, Bevington was able to fulfill a long-time dream and obtain a Heidelberg press [29], which made colour printing much simpler [30] and allowed book production at Coach House to increase [31]. Once the Heidelbergs were in-house and printing became less time-intensive [32], Bevington experimented with new  technologies for typesetting and publishing [33], and during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, was working at the forefront of publishing technology.

technologies for typesetting and publishing [33], and during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, was working at the forefront of publishing technology.

Measurable quality [34], cohesiveness [35], and appropriateness [36] come to mind when Bevington thinks about creating a fine piece of printing, and over the years, other considerations have contributed to the Coach House aesthetic, including his insistence upon working with living Canadians and upon books being the objects of their own design [37]. His business model has also helped Coach House survive over the years [38].

Nowadays, Bevington is semi-retired, enjoys cycling and canoeing, and allows himself to be a casual photographer, freed from the creative constraints of his formal training as a darkroom technician [39]. He continues as "Head Coach" at Coach House Press, happy to be working in an era when computer technology, as it relates to book design and printing, has moved into the creative stage [40].

Bevington has received many awards for his work over the years. Most recently, he was appointed to the Order of Canada for his contribution to the field of communications.

Hipworth, Sarah. Personal interviews with Stan Bevington, 30-31 January, 2009, at Coach House Press, Toronto

Coach House Press papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto