The Business of an Eighteenth-Century Printing Office: The Neilson Paybook

Patricia Lockhart Fleming, University of Toronto

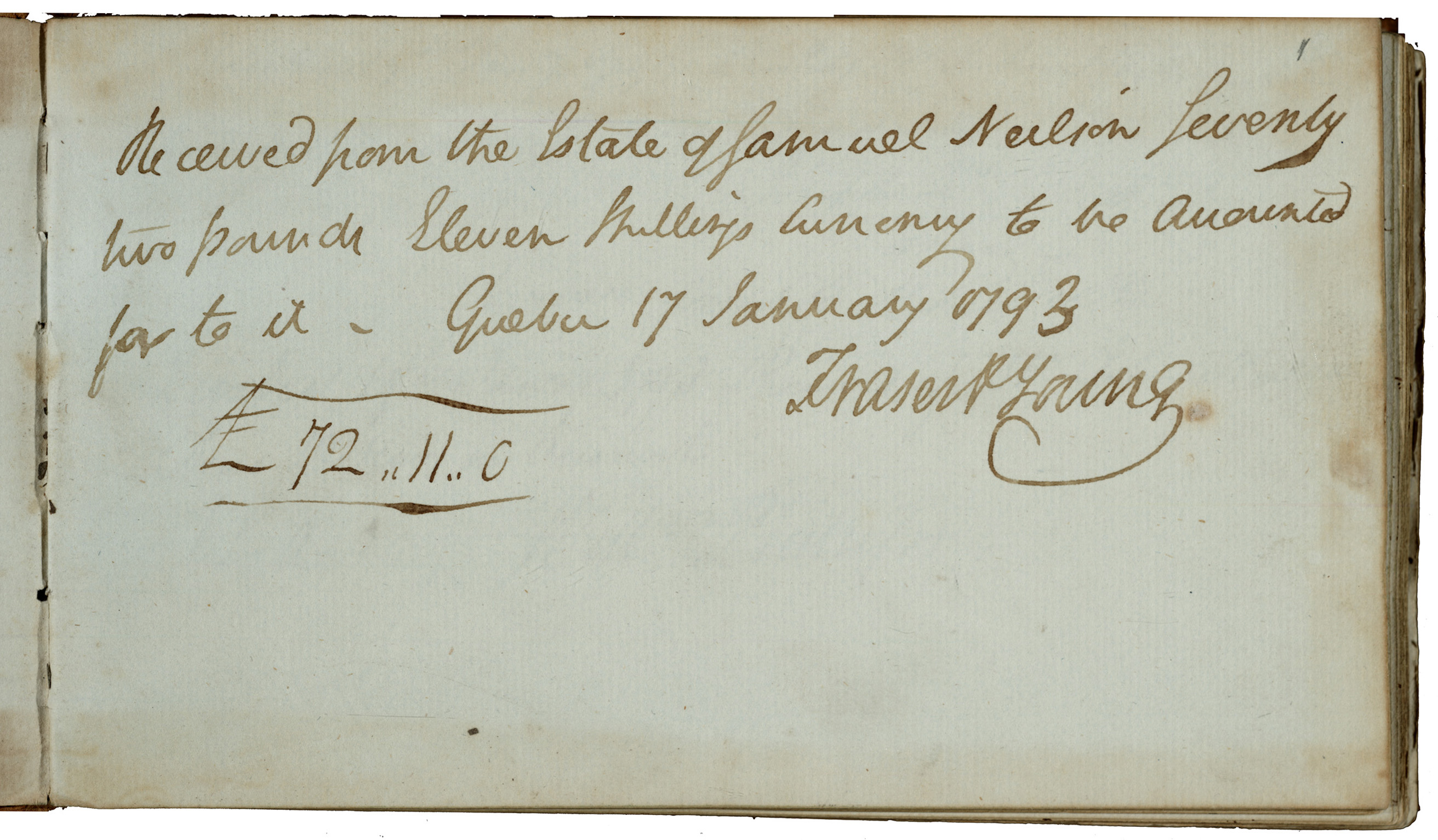

John Neilson was just sixteen when he chose this blank note book (now at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at University of Toronto) to record his expenditures as the new proprietor at the printing office of the Quebec Gazette/ La Gazette de Québec. The story opens with tragic news, an entry dated 17 January 1793 noting the receipt of £72  11s from the Estate of Samuel Neilson, John's able and energetic brother who had died five days earlier, at the age of twenty-three. Born in Scotland, the Neilsons came to the city of Quebec to learn the printing trade in the office of William Brown, their maternal uncle and the founder in 1764 of the province's first press. Sam, who arrived in 1785, succeeded to the business in 1789 when Brown died. John joined him in 1790 or 1791 and a third brother, William, came in 1795 but returned to Scotland several years later. Successful as printers, publishers, and booksellers, the Brown/Neilson dynasty continued well into the nineteenth century under the direction of John Neilson and then his sons, another generation's Samuel and William.

11s from the Estate of Samuel Neilson, John's able and energetic brother who had died five days earlier, at the age of twenty-three. Born in Scotland, the Neilsons came to the city of Quebec to learn the printing trade in the office of William Brown, their maternal uncle and the founder in 1764 of the province's first press. Sam, who arrived in 1785, succeeded to the business in 1789 when Brown died. John joined him in 1790 or 1791 and a third brother, William, came in 1795 but returned to Scotland several years later. Successful as printers, publishers, and booksellers, the Brown/Neilson dynasty continued well into the nineteenth century under the direction of John Neilson and then his sons, another generation's Samuel and William.

Starting with William Brown in 1764, family members were prodigious record keepers.  The Neilson Collection at Library and Archives Canada weighs in at 191 volumes, and both the Archives nationales du Québec à Montréal and the Archives nationales du Québec à Québec hold additional papers. So, what can a single book of receipts reveal? With coaxing, quite a lot. Coaxing is necessary since few entries specify more than “one month's wages/un mois de gages.” We are left to deduce from the amounts earned which workers were compositors, rewarded for speed and accuracy in

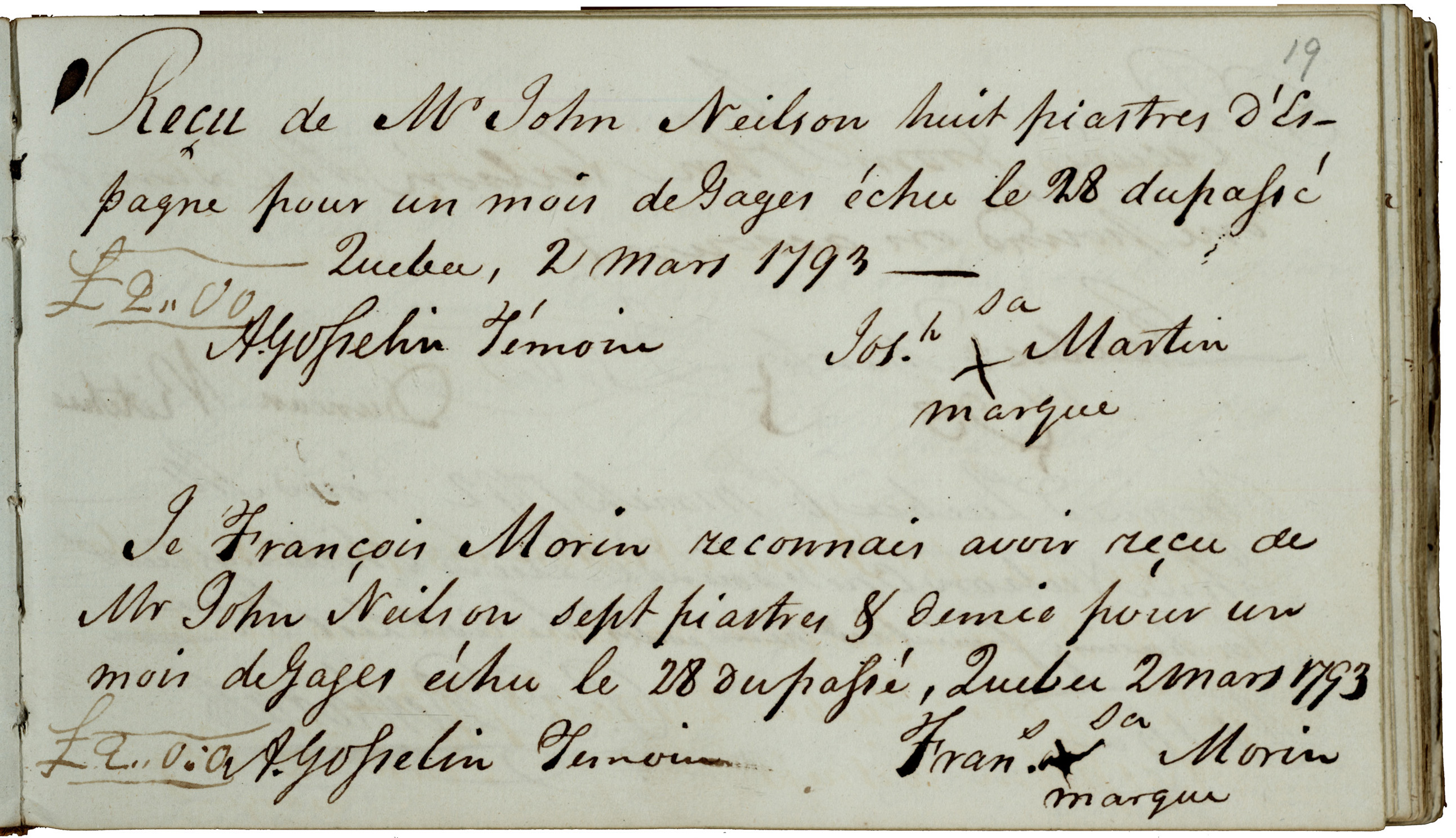

The Neilson Collection at Library and Archives Canada weighs in at 191 volumes, and both the Archives nationales du Québec à Montréal and the Archives nationales du Québec à Québec hold additional papers. So, what can a single book of receipts reveal? With coaxing, quite a lot. Coaxing is necessary since few entries specify more than “one month's wages/un mois de gages.” We are left to deduce from the amounts earned which workers were compositors, rewarded for speed and accuracy in  setting text letter by letter, and who was the pressman patiently pulling the bar of the heavy wooden press. Following the money is easier once the currency is untangled. Most accounts are recorded in £(pounds), s(shillings), and d(pence) with the odd guinea (21s) for professional fees. Pounds may be translated as Louis, shillings as shelins, and pence as sols or sous. Some payments are written in dollars, others, especially in French receipts, as piastres or piastres d'Espagne, although the total in pounds is usually supplied (4 dollars or piastres to the pound).

setting text letter by letter, and who was the pressman patiently pulling the bar of the heavy wooden press. Following the money is easier once the currency is untangled. Most accounts are recorded in £(pounds), s(shillings), and d(pence) with the odd guinea (21s) for professional fees. Pounds may be translated as Louis, shillings as shelins, and pence as sols or sous. Some payments are written in dollars, others, especially in French receipts, as piastres or piastres d'Espagne, although the total in pounds is usually supplied (4 dollars or piastres to the pound).

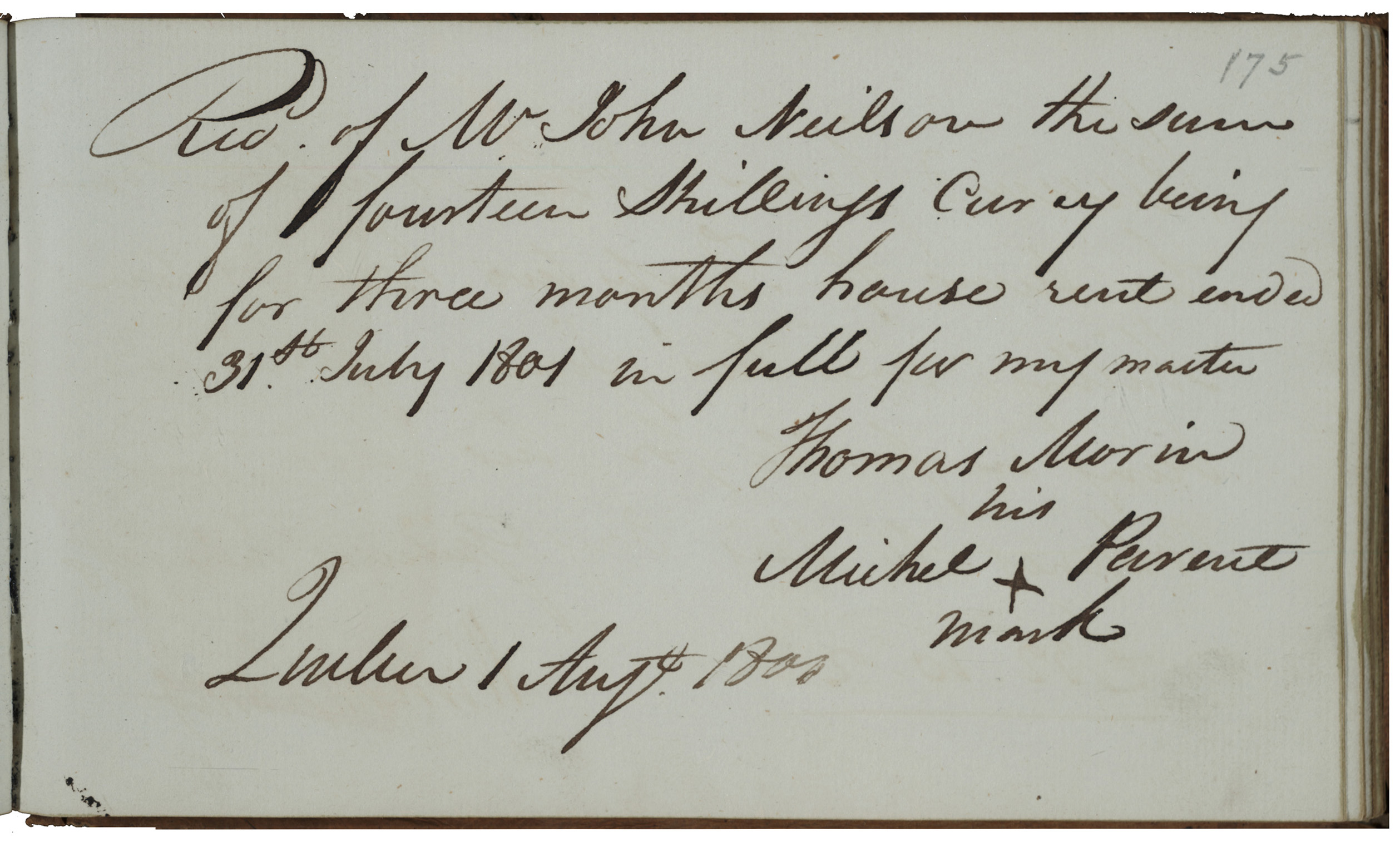

Neilson used his small leather-bound book (11.8 x 19 cm) from January 1793 to July 1798, then once more in 1801 (page 175) to record three months’ house rent, before leaving the remaining pages blank. His shop was busy, probably employing about seven workers each year, although monthly records are seldom regular. As an example,  Charles Hurst, one of Brown's compositors as early as 1786, signed his payments for November 1792 to March 1793 (with a bonus for extra night work), July and August 1793, and January to March 1794. It is unlikely that he left the shop in the period between receipts, although there is an instance of one printer who may have returned for a couple of months. Louis Roy, who was paid £6 in June 1795, had joined William Brown as an apprentice in 1786 then moved to Montreal to work for Fleury Mesplet, that city’s first printer. In 1792 he was recruited by John Graves Simcoe, the founding lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, to set up the first press in Ontario, at Niagara-on-the-Lake. Roy was printing by January 1793 but resigned in the autumn of 1794 and returned to Quebec where we find him in the Gazette office in June 1795. By August he and one of his brothers had launched a short-lived newspaper in Montreal. John Bennett, another Neilson apprentice who was promoted to foreman by 1794, joined the Roys in their Montreal venture and then travelled to York (Toronto) when he was named King`s printer for Upper Canada. Even more adaptable was James Brown, a Scottish printer and bookbinder who left Neilson’s to open his own bookshop and bindery in Montreal. Later, as the owner of Canada’s first paper mill, Brown noted his former employer’s prosperity as “the largest consumer of paper” in the country (see Dictionary of Canadian Biography entry for Neilson). Neilson was also doing business with other members of the printing trade such as William Moore, Thomas Cary, William Cowan, and Pierre-Édouard Desbarats, translator of the Gazette from 1794 to 1808.

Charles Hurst, one of Brown's compositors as early as 1786, signed his payments for November 1792 to March 1793 (with a bonus for extra night work), July and August 1793, and January to March 1794. It is unlikely that he left the shop in the period between receipts, although there is an instance of one printer who may have returned for a couple of months. Louis Roy, who was paid £6 in June 1795, had joined William Brown as an apprentice in 1786 then moved to Montreal to work for Fleury Mesplet, that city’s first printer. In 1792 he was recruited by John Graves Simcoe, the founding lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, to set up the first press in Ontario, at Niagara-on-the-Lake. Roy was printing by January 1793 but resigned in the autumn of 1794 and returned to Quebec where we find him in the Gazette office in June 1795. By August he and one of his brothers had launched a short-lived newspaper in Montreal. John Bennett, another Neilson apprentice who was promoted to foreman by 1794, joined the Roys in their Montreal venture and then travelled to York (Toronto) when he was named King`s printer for Upper Canada. Even more adaptable was James Brown, a Scottish printer and bookbinder who left Neilson’s to open his own bookshop and bindery in Montreal. Later, as the owner of Canada’s first paper mill, Brown noted his former employer’s prosperity as “the largest consumer of paper” in the country (see Dictionary of Canadian Biography entry for Neilson). Neilson was also doing business with other members of the printing trade such as William Moore, Thomas Cary, William Cowan, and Pierre-Édouard Desbarats, translator of the Gazette from 1794 to 1808.

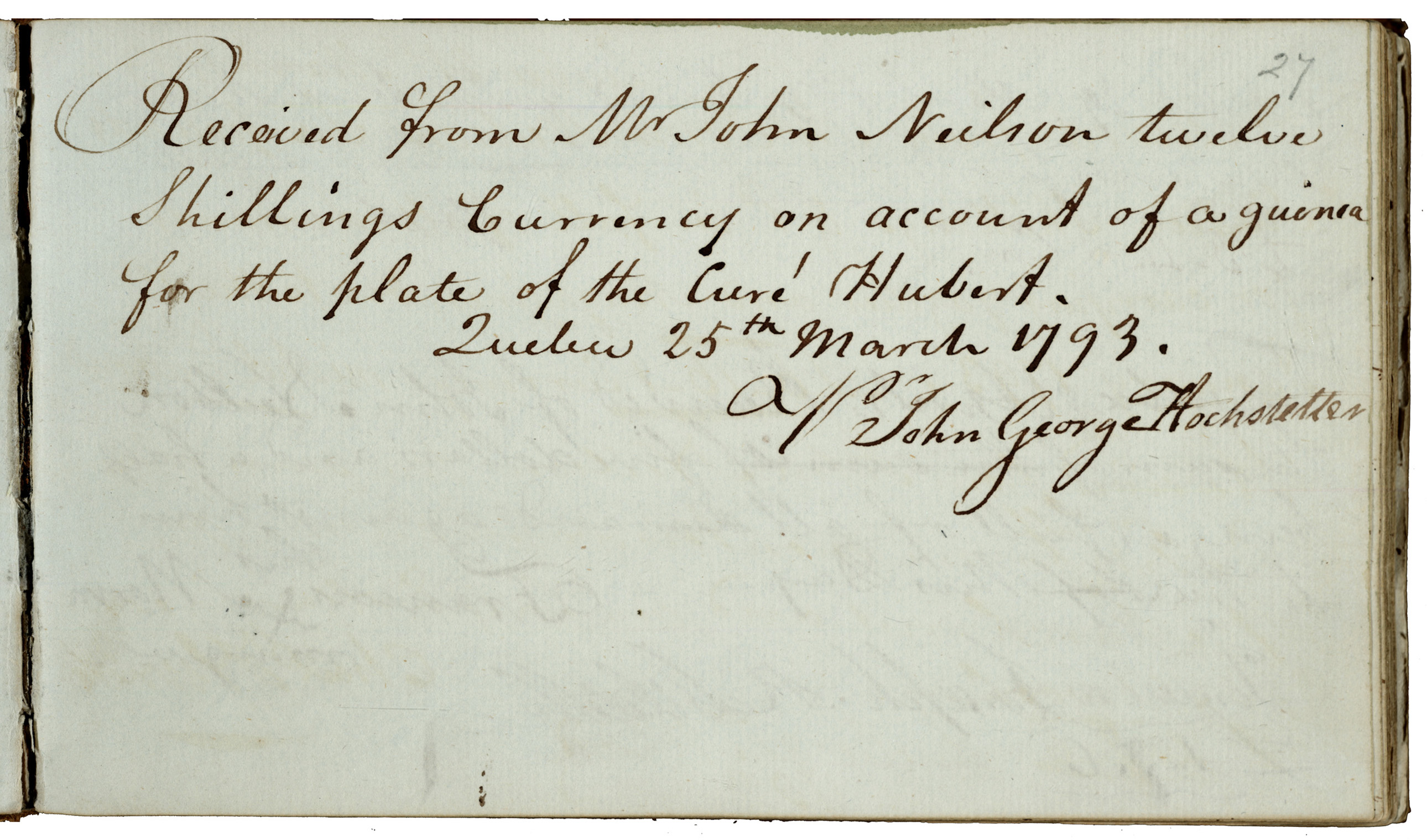

Readers of Neilson’s publications are absent from his paybook except by implication in the payments for delivery of the paper. In 1793 and 1794 the task of “carrying” included copies of the Quebec Magazine /Le Magasin de Québec (1792 -94), Sam Neilson’s ambitious monthly. A rare 1793 sighting of the artist John George Hochstetter, one of the Magazine’s illustrators, confirms attribution to him of an engraved portrait of Auguste David Hubert, late curé of Notre Dame de Québec.

Although the majority of John Neilson’s payments were made to men, nine women are named in the paybook. One attended Samuel Neilson in his final illness, three were paid for unspecified services, and five were earning a monthly wage. Only one signed her own name, the others with a mark. It is tempting to speculate that they worked in Neilson’s bindery, probably folding and sewing, but that is another secret hidden in this intriguing volume.

Although the majority of John Neilson’s payments were made to men, nine women are named in the paybook. One attended Samuel Neilson in his final illness, three were paid for unspecified services, and five were earning a monthly wage. Only one signed her own name, the others with a mark. It is tempting to speculate that they worked in Neilson’s bindery, probably folding and sewing, but that is another secret hidden in this intriguing volume.

Alston, Sandra. “The Early History of the Quebec Gazette.” The Halycon 6 (November 1990): 1-2.

Chassé, Sonia, Rita Girard-Wallot, and Jean-Pierre Wallot. “Neilson, John.” In Dictionary of Canadian Biography VII. Available online at: http://www.biographi.ca/index-e.html

Fleming, Patricia Lockhart, and Sandra Alston. Early Canadian Printing: A Supplement to Marie Tremaine’s ‘A Bibliography of Canadian Imprints, 1751-1800’. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999.

History of the Book in Canada, eds. Patricia Lockhart Fleming, Gilles Gallichan, Yvan Lamonde, I. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Tremaine, Marie. A Bibliography of Canadian Imprints, 1751-1800. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1952.

MS Coll 210 boxes 3/4 item 3, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto

![Letter from Nellie L. McClung to Dorothy [Dumbrille], 3 October 1946](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01132-002.jpg?itok=F0ZAXt2J)

![Letter from Nellie L. McClung to Dorothy [Dumbrille], 3 October 1946](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01132-003.jpg?itok=k9oRwxiy)

![Letter from Nellie L. McClung to Dorothy [Dumbrille], 3 October 1946](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01132-004.jpg?itok=-XMBZXmo)

![Letter from Nellie L. McClung to Dorothy [Dumbrille], 3 October 1946](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01132-005.jpg?itok=Y6xtwjBh)

![Letter from Nellie L. McClung to Dorothy [Dumbrille], 3 October 1946](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01132-006.jpg?itok=Qoym5HFS)

![Louise Dennys interview by Roy MacSkimming [audio interview], 26 August 1999](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/mic-50-128x128-dennys.png?itok=XrPUttI-)

![Anna Porter interview by Roy MacSkimming [audio interview], 20 October 1998](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/mic-50-128x128-porter.png?itok=yc8i6mKs)