Nellie McClung’s Literary Legacy

Linda Quirk, Queen's University

One of the most effective women’s rights activists of her day, Nellie Letitia (Mooney) McClung (1873-1951) was a leading figure in the suffrage campaign which finally won the vote for Canadian women in 1916. The first woman to be elected to the Manitoba legislature in 1921, McClung worked for a wide range of social reforms from property rights for married women to improved working conditions in urban sweat shops. She was one of the “Famous Five” who won  for women the right to be considered “persons” under the law throughout the British Empire (1929). It was a decision, as McClung notes in The Stream Runs Fast, which “came as a surprise to many women in Canada” since many had not realized “that they were not persons until they heard it stated that they were.” Throughout her career she played a leadership role in numerous organizations, from the Canadian Authors Association to the board of governors of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. In 1938, McClung was the only woman to serve on the Canadian delegation to the League of Nations in Geneva.

for women the right to be considered “persons” under the law throughout the British Empire (1929). It was a decision, as McClung notes in The Stream Runs Fast, which “came as a surprise to many women in Canada” since many had not realized “that they were not persons until they heard it stated that they were.” Throughout her career she played a leadership role in numerous organizations, from the Canadian Authors Association to the board of governors of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. In 1938, McClung was the only woman to serve on the Canadian delegation to the League of Nations in Geneva.

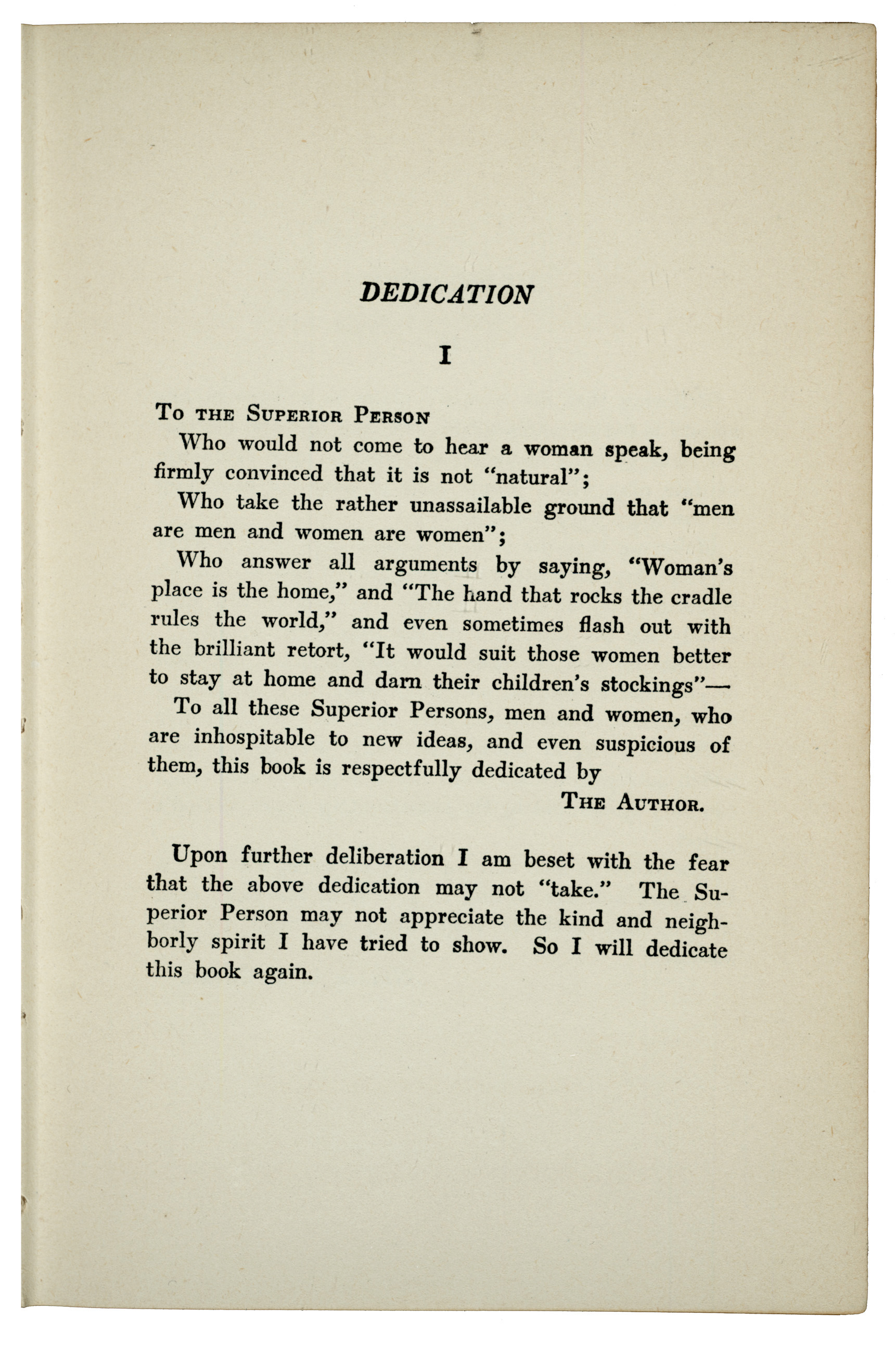

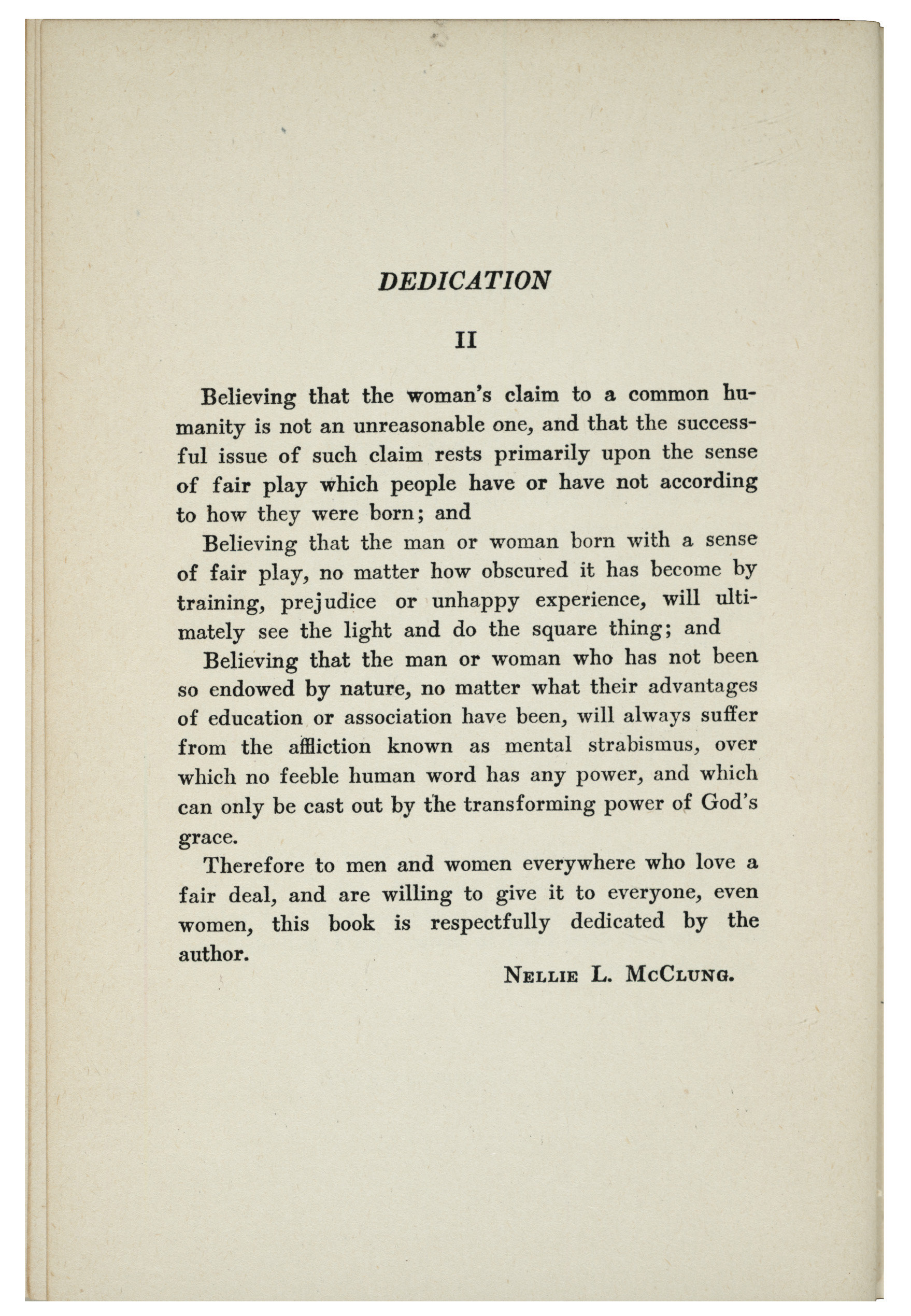

Like her friend E. Pauline Johnson, McClung was a popular platform performer. She offered dramatic readings of her own fiction in order to supplement her income from writing. McClung was also an exceptionally effective political speaker who was able to win over a crowd with her insight, exuberance, and wit. In many ways her most important book, In Times Like These (McLeod & Allen, Toronto, 1915) is a collection of McClung’s speeches. The book contains two dedications which, taken together, illustrate the charm and impact of her approach. Initially the book is dedicated to the superior person who is “firmly convinced” that a “[w]oman’s place is in the home” but, imagining that such a person will not

Like her friend E. Pauline Johnson, McClung was a popular platform performer. She offered dramatic readings of her own fiction in order to supplement her income from writing. McClung was also an exceptionally effective political speaker who was able to win over a crowd with her insight, exuberance, and wit. In many ways her most important book, In Times Like These (McLeod & Allen, Toronto, 1915) is a collection of McClung’s speeches. The book contains two dedications which, taken together, illustrate the charm and impact of her approach. Initially the book is dedicated to the superior person who is “firmly convinced” that a “[w]oman’s place is in the home” but, imagining that such a person will not  appreciate the “neighbourly spirit” of the dedication, she recants the first and makes her point with gently prodding humour when she re-dedicates the book to those who are willing to give everyone a fair deal, “even women.”

appreciate the “neighbourly spirit” of the dedication, she recants the first and makes her point with gently prodding humour when she re-dedicates the book to those who are willing to give everyone a fair deal, “even women.”

Although her political triumphs have tended to eclipse her literary career, McClung was an accomplished and popular author during her lifetime. She published in a range of periodicals. While many of her contemporaries found it extremely difficult to publish books in Canada, her extensive list of monographs includes novels, collections of short stories, collections of essays, and two volumes of autobiography, all published in her native country. Many of these titles were also published in London and New York. McClung became a literary  celebrity almost overnight, in much the same manner as Lucy Maud Montgomery, and in the same year (1908). McClung’s Sowing Seeds in Danny and Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables were fabulous debut novels; both were about irrepressible young girls with overactive imaginations who overcame appalling circumstances; both observe the absurdities of life in a small community with humour and insight; both were immediate best-sellers. Furthermore, in the publishing arrangements for their first novels, both emerging authors agreed to disadvantageous business arrangements with publishers-agents who took advantage of their inexperience.

celebrity almost overnight, in much the same manner as Lucy Maud Montgomery, and in the same year (1908). McClung’s Sowing Seeds in Danny and Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables were fabulous debut novels; both were about irrepressible young girls with overactive imaginations who overcame appalling circumstances; both observe the absurdities of life in a small community with humour and insight; both were immediate best-sellers. Furthermore, in the publishing arrangements for their first novels, both emerging authors agreed to disadvantageous business arrangements with publishers-agents who took advantage of their inexperience.

McClung got her start as an author when her mother-in-law suggested that she submit a story to a contest run by Colliers Weekly. Although the story didn’t win, she later submitted it to the Methodist Book and Publishing House and, at the suggestion of book steward William Briggs, turned the story into a novel: Sowing Seeds in Danny. In Firing the Heather: The Life and Times of Nellie McClung, Hallett and Davis observe that early drafts of the novel were criticized by the publisher’s reader Jean Graham for lacking moral subtlety; later drafts were criticized by the publisher’s editor E.S. Caswell for treating serious subjects in a light-hearted manner. Hallett and Davis report that, despite his reservations, Caswell anticipated that the novel would be a runaway best-seller. They note that he took advantage of McClung’s inexperience and also undermined his employer, the Methodist Book and Publishing House. Caswell proposed that he would act as McClung’s agent, securing an American publisher and making a better deal with another Canadian publisher, in exchange for an astonishing sum: half of her royalties. Although Caswell failed to deliver on his promises and McClung eventually understood the dubious nature of the arrangement, she faithfully paid him ten percent of the royalties on her first book. The novel was a best-seller for Briggs (Toronto), Doubleday (New York), and Hodder & Stoughton (London).

Although McClung stayed with Briggs for her second novel (The Second Chance, 1910) and her first collection of short stories (The Black Creek Stopping-House and Other Stories, 1912), Thomas Allen became  her Canadian publisher in 1915. It was a fruitful relationship for both author and publisher, one which produced thirteen monographs over a period of thirty years. In a letter to Dorothy Dumbrille, dated 3 October 1946, McClung advises her friend: “Mr. Allen is pleased to have your poems, and I hope will soon see the book. He is a very good publisher. He and I have had business dealings all these years, and there has never been a cloud between us. He is honest and forthright [which] is not true of all publishers and you can always depend on what he says.”

her Canadian publisher in 1915. It was a fruitful relationship for both author and publisher, one which produced thirteen monographs over a period of thirty years. In a letter to Dorothy Dumbrille, dated 3 October 1946, McClung advises her friend: “Mr. Allen is pleased to have your poems, and I hope will soon see the book. He is a very good publisher. He and I have had business dealings all these years, and there has never been a cloud between us. He is honest and forthright [which] is not true of all publishers and you can always depend on what he says.”

The many similarities between Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables and McClung’s Sowing Seeds in Danny have led  people to wonder why Anne Shirley remains one of the best-known and best-loved characters in Canadian fiction while Pearl Watson is largely forgotten. In her time, McClung was one of the most popular Canadian authors, but much of her writing has failed to transcend its time and place, perhaps, ironically enough, because of the confident social interventions which are the central message of her fiction. While modern readers may appreciate the novel’s feminist perspective and its subtle insights into the absurdities of human nature, these strengths are undermined by sometimes flatly stereotypical characters. While they are both delightfully irrepressible, Pearl Watson is too good to be true, and readers tend to like Anne Shirley all the better for the many “scrapes” which punctuate her story. The major difficulty, however, is that Sowing Seeds in Danny expresses a moralistic indictment of “demon alcohol,” lacking both perspective and subtlety. Modern readers may not understand the central place of the temperance movement in early Canadian society, and, thanks to the changes effected by McClung and her contemporaries, we may not appreciate the implications of alcohol-induced domestic violence at a time when women and children had few legal rights. The novel is a temperance sermon in disguise. McClung acknowledges this in The Stream Runs Fast when she quips: “my earnest hope is that the disguise did not obscure the sermon.”

people to wonder why Anne Shirley remains one of the best-known and best-loved characters in Canadian fiction while Pearl Watson is largely forgotten. In her time, McClung was one of the most popular Canadian authors, but much of her writing has failed to transcend its time and place, perhaps, ironically enough, because of the confident social interventions which are the central message of her fiction. While modern readers may appreciate the novel’s feminist perspective and its subtle insights into the absurdities of human nature, these strengths are undermined by sometimes flatly stereotypical characters. While they are both delightfully irrepressible, Pearl Watson is too good to be true, and readers tend to like Anne Shirley all the better for the many “scrapes” which punctuate her story. The major difficulty, however, is that Sowing Seeds in Danny expresses a moralistic indictment of “demon alcohol,” lacking both perspective and subtlety. Modern readers may not understand the central place of the temperance movement in early Canadian society, and, thanks to the changes effected by McClung and her contemporaries, we may not appreciate the implications of alcohol-induced domestic violence at a time when women and children had few legal rights. The novel is a temperance sermon in disguise. McClung acknowledges this in The Stream Runs Fast when she quips: “my earnest hope is that the disguise did not obscure the sermon.”

Fiamengo, Janice. “A Legacy of Ambivalence: Responses to Nellie McClung.” Journal of Canadian Studies 34.4 (1999-2000): 70-87.

Hallett, Mary and Marilyn Davis. Firing the Heather: The Life and Times of Nellie McClung. Saskatoon: Fifth House, 1993.

McClung, Nellie. Sowing Seeds in Danny. Toronto: Wm. Briggs, 1908.

—. The Stream Runs Fast: My Own Story. Toronto: Thomas Allen, 1945.

Dorothy Dumbrille fonds, Queen’s University Archives

Letters of Nellie Letitia McClung, Queen's University Archives

Lorne and Edith Pierce collection. 1911-1959, predominant Katherine and John Garvin Hale collection, Queen's University Archives

![Beautiful Joe / by Marshall Saunders ; with an introduction [by] Hezekiah Butterworth ; illustrated by Charles Copeland](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01008.jpg?itok=E8hM-R1C)

![Beautiful Joe / by Marshall Saunders ; with an introduction [by] Hezekiah Butterworth ; illustrated by Charles Copeland](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01008-002.jpg?itok=vUuiEqF8)