Helen Humphreys’s Toronto Mythologies

Kiley Kapuscinski, Queen’s University

Since her emergence onto the Canadian literary scene in the 1980s, Helen Humphreys (b.1961) has increasingly distinguished herself as a writer gifted with a range of expression. From early works of poetry, drama, young-adult fiction, and screenwriting to her more recent novels and genre-bending short prose collection, Humphreys has demonstrated an interest in a variety of literary forms. Yet her adult fiction has garnered her the greatest recognition. Although her first novella,  Ethel on Fire (1991), was largely dismissed by critics as an “extended skit,” Leaving Earth (1998) was honored with the City of Toronto Book Award and named a New York Times Notable Book. Her subsequent fiction, including Afterimage (2000), The Lost Garden (2002), Wild Dogs (2004), The Frozen Thames (2007), and Coventry (2008), have similarly met with critical acclaim.

Ethel on Fire (1991), was largely dismissed by critics as an “extended skit,” Leaving Earth (1998) was honored with the City of Toronto Book Award and named a New York Times Notable Book. Her subsequent fiction, including Afterimage (2000), The Lost Garden (2002), Wild Dogs (2004), The Frozen Thames (2007), and Coventry (2008), have similarly met with critical acclaim.

Yet Humphreys’s prose has not always been met with instant appeal. In  particular, her celebrated first novel, Leaving Earth, creates a cultural mythology around Toronto that was originally imagined and received in a very different manner. This earlier rendering of Toronto in “Watermarks” was largely inspired by Humphreys’s desire to foment a consciousness about Toronto and to “make [her] Toronto real and imagined—to [make it] exist as other cities which have a cultural mythology attached to them.” However, “Watermarks” remains unpublished, thereby obscuring the important story it tells about twentieth-century Canadian publishers’ preferences and the stories behind stories.

particular, her celebrated first novel, Leaving Earth, creates a cultural mythology around Toronto that was originally imagined and received in a very different manner. This earlier rendering of Toronto in “Watermarks” was largely inspired by Humphreys’s desire to foment a consciousness about Toronto and to “make [her] Toronto real and imagined—to [make it] exist as other cities which have a cultural mythology attached to them.” However, “Watermarks” remains unpublished, thereby obscuring the important story it tells about twentieth-century Canadian publishers’ preferences and the stories behind stories.

Humphreys’s unpublished fiction is a synecdochical reminder of the scores of early-career manuscripts that encounter considerable difficulty in securing a sympathetic publisher, signaling how the body of fiction published in Canada offers but a glimpse of the total number of manuscripts in circulation. Several  notable twentieth-century novelists have, on occasion, found themselves peddling their writing for extended periods due to an un-established literary reputation, publishers’ intuitions about a lack of public interest in their topics or form, or publishers’ preference for the continually shifting aesthetics of “quality” writing, amongst other factors. Stephen Leacock’s widely popular Literary Lapses (1910), for example, was refused by Houghton, Mifflin and Company before Leacock privately published the collection through the Gazette Printing Company. Similarly, Nino Ricci’s Lives of the Saints (1990) faced numerous rejections before being accepted by Cormorant Books. Terry Fallis’s The Best-Laid Plans (2007) provides a contemporary complement for Leacock’s Lapses as an example of an acclaimed fictional work that was initially self-published. There are, of course, also countless manuscripts that, like Humphreys’s “Watermarks,” have never reached print, including: Frank Parker Day’s six unpublished romances; Hugh MacLennan’s “So All Their Praises” (1933) and “Man Should Rejoice” (1937); Margaret Atwood’s “Up in the Air So Blue” (1961); and Marian Engel’s “The Pink Sphinx” (1958), “Women Travelling Alone” (1962), “Death Comes for the Yaya” (1964), and “Lost Heir and Happy Families” (1964).

notable twentieth-century novelists have, on occasion, found themselves peddling their writing for extended periods due to an un-established literary reputation, publishers’ intuitions about a lack of public interest in their topics or form, or publishers’ preference for the continually shifting aesthetics of “quality” writing, amongst other factors. Stephen Leacock’s widely popular Literary Lapses (1910), for example, was refused by Houghton, Mifflin and Company before Leacock privately published the collection through the Gazette Printing Company. Similarly, Nino Ricci’s Lives of the Saints (1990) faced numerous rejections before being accepted by Cormorant Books. Terry Fallis’s The Best-Laid Plans (2007) provides a contemporary complement for Leacock’s Lapses as an example of an acclaimed fictional work that was initially self-published. There are, of course, also countless manuscripts that, like Humphreys’s “Watermarks,” have never reached print, including: Frank Parker Day’s six unpublished romances; Hugh MacLennan’s “So All Their Praises” (1933) and “Man Should Rejoice” (1937); Margaret Atwood’s “Up in the Air So Blue” (1961); and Marian Engel’s “The Pink Sphinx” (1958), “Women Travelling Alone” (1962), “Death Comes for the Yaya” (1964), and “Lost Heir and Happy Families” (1964).

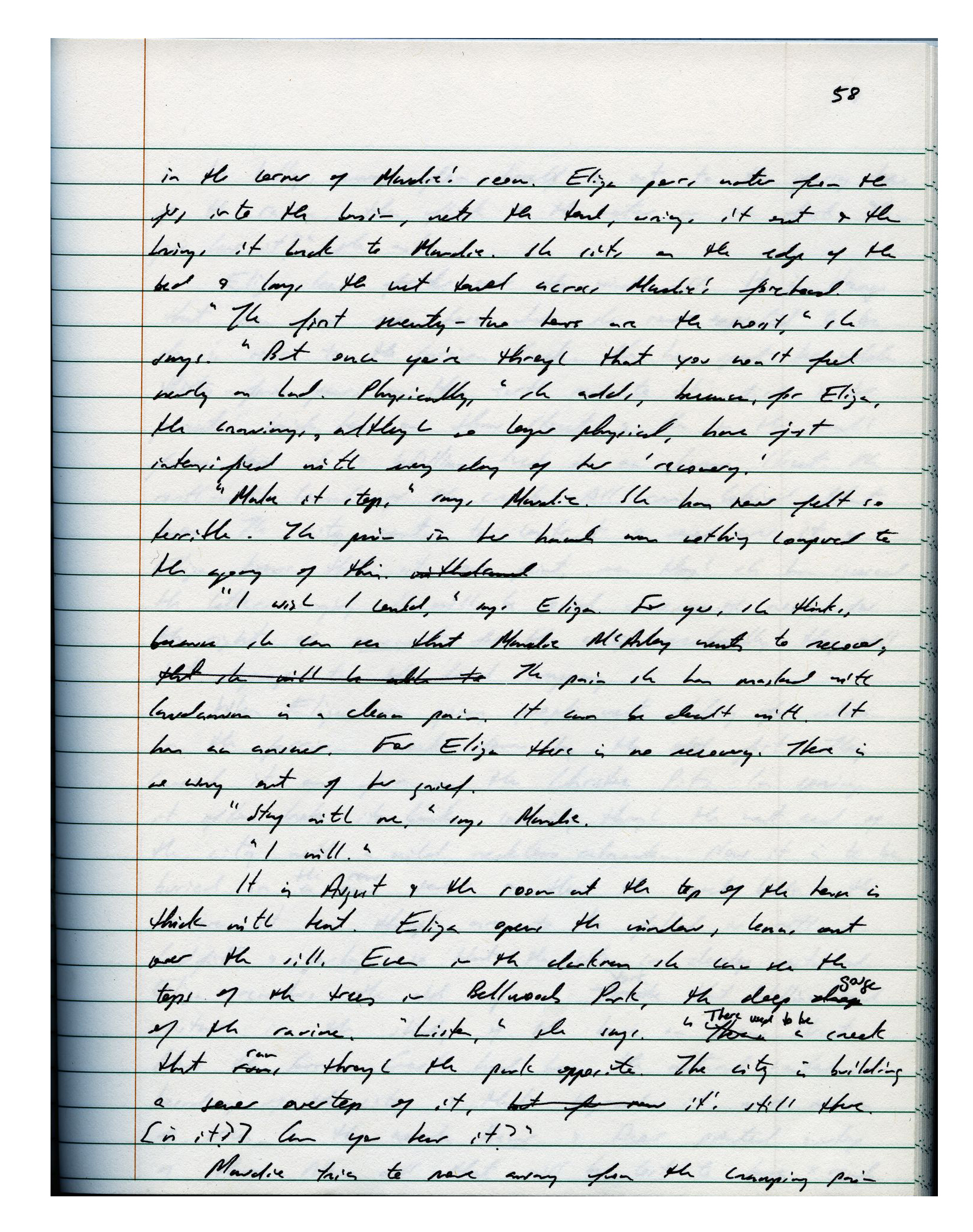

Notwithstanding the rejections that early-career manuscripts often encounter vis-à-vis publishers’ frequently narrow, but necessary, selection criteria, such documents often provide valuable insight into a writer’s corpus. Specifically, Humphreys’s “Watermarks” reveals how her interest in recovering and investing with story aspects of the Toronto cityscape predates her trials with Leaving Earth. Written in the early 1990s in the years immediately prior to Leaving Earth, “Watermarks” offers a split narrative that recounts the story of Eliza Bass, a young woman living in 1885 Toronto who endeavors to map the Garrison Creek, and Claire, a woman of present-day Toronto who is inspired by Eliza’s cartography to investigate the creek’s disappearance. In following the interactions of these two women with their respective urban surroundings, “Watermarks” emphasizes the mapping and reclaiming of lost Toronto landmarks. Locations such as the Garrison Creek, Harry Piper’s Zoological Gardens, and the Massey-Harris building play a pivotal role in the creation of Toronto’s unique mythology and evince Humphreys’s sense for how physical geography influences the ways we think about, and form connections to, cities.

However, despite Humphreys’s obvious investments in “Watermarks,” which she described at the time of its writing as a work that “mean[t] more to [her] than anything else [she had] ever done,” and the extensive research she conducted for the novel, which led to her spending two years in the city archives and developing correspondences with other Toronto writers such as Michael Ondaatje and Margaret Atwood, Humphreys was ultimately unable to gain a publisher for her first novel. The reasons for this are manifold. Publishers such as McClelland & Stewart and Anansi objected, respectively, to the unconventional format of the manuscript (whose narrative is followed by a lengthy “Documents” section), and to its extensive historical detail. Although Torontonians’ interest in the Garrison Creek expanded quickly towards the end of the decade as restoration projects grew, publishers’ early

However, despite Humphreys’s obvious investments in “Watermarks,” which she described at the time of its writing as a work that “mean[t] more to [her] than anything else [she had] ever done,” and the extensive research she conducted for the novel, which led to her spending two years in the city archives and developing correspondences with other Toronto writers such as Michael Ondaatje and Margaret Atwood, Humphreys was ultimately unable to gain a publisher for her first novel. The reasons for this are manifold. Publishers such as McClelland & Stewart and Anansi objected, respectively, to the unconventional format of the manuscript (whose narrative is followed by a lengthy “Documents” section), and to its extensive historical detail. Although Torontonians’ interest in the Garrison Creek expanded quickly towards the end of the decade as restoration projects grew, publishers’ early  objections to “Watermarks” reveal the importance of timely thematics to contemporary publishers, and the financial focus and often conventional tastes of Canada’s large publishing houses. Years later, Humphreys’s return to the history of the Garrison Creek in her second unpublished novel, “Franklin’s Library,” demonstrates the enduring influence of the tributary. Yet its early influence, alongside other Toronto landmarks, in shaping Humphreys’s preliminary thinking about Leaving Earth and the connections between Toronto’s inhabitants and its geography, signals the deeply palimpsestic quality of Humphreys’s fiction.

objections to “Watermarks” reveal the importance of timely thematics to contemporary publishers, and the financial focus and often conventional tastes of Canada’s large publishing houses. Years later, Humphreys’s return to the history of the Garrison Creek in her second unpublished novel, “Franklin’s Library,” demonstrates the enduring influence of the tributary. Yet its early influence, alongside other Toronto landmarks, in shaping Humphreys’s preliminary thinking about Leaving Earth and the connections between Toronto’s inhabitants and its geography, signals the deeply palimpsestic quality of Humphreys’s fiction.

Bearing the marks of her earlier writing, Leaving Earth echoes the split narrative of “Watermarks” in dually focusing on the airborne adventures of Grace O’Gorman and Willa Briggs and on the earthbound trials of an eleven-year-old Jewish girl, Maddy Stewart. The aerial views of the city offered in the novel, mapping Toronto’s Air Harbour, the Sunnyside Stadium, Hanlan’s Amusement Park, and other waterside sites, enable Humphreys to document major landmarks of 1930s Toronto that helped shape the city’s ethos but that have almost completely disappeared from the current cultural consciousness. Moreover, this focus on lost landscapes recalls the navigational themes and the documenting of vanished sites that characterize “Watermarks,” indicating the continuities between the two works and their shared interest in bringing to light a uniquely Toronto mythology that, for Humphreys, emerges from the relationship between the city’s physical sites and its inhabitants. Although she was attempting to (re)chart important territory in Leaving Earth, Humphreys again encountered considerable difficulty securing a literary agent or a publisher. Her manuscript was rejected by Norton, Knopf, Macmillan, McClelland & Stewart, and others. The publication of the novel in 1998 byHarperCollins would ultimately launch Humphreys’s career as a prose writer. However, obscured in the novel’s publication are the traces it carries of Humphreys’s earlier writing, and thus the ways in which the novel had, by the time of its printing, already accrued its own buried mythology.

Buonaguro, Gina. “Profile 2: Helen Humphreys.” Profile Kingston Magazine. 14 May 2003: 24-7.

Drobot, Eve. “Fruit Pits and Burl Bowls: Some Very, Very Funny Heritage Minutes.” Review of Ethel on Fire. Globe and Mail. 25 July 1992: C7.

Humphreys, Helen. “Overcoming Fear of Flying.” Interview with Eva Tihanyi. Books in Canada 30:2 (August 1998): 16.

Frank Parker Day fonds, Dalhousie University

Marian Engel fonds, McMaster University

Helen Humphreys fonds, Queen’s University Archives

Hugh MacLennan papers, McGill University

Margaret Atwood Papers, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto

![Letter from Charles W. Jefferys to [Ryerson Press] re Economic History Readers](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01161-002.jpg?itok=m_xoaR9O)

![Letter from Peter Miller (Contact Press) to Peggy [Margaret Atwood], 17 October 1966](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/canpub/CP01165.jpg?itok=ZhQq1Wci)