Marian Engel: A Life in Writing

Kathy Garay, McMaster University

Hugh MacLennan, a well-established writer, and supervisor of Engel’s M.A. thesis (completed at McGill in 1957), provided early support and useful publishing contacts for her. On his recommendation the prestigious New York literary agents Russell and Volkening agreed to represent her work. Her first published novel, No Clouds of Glory (originally titled Sarah Bastard’s Notebook) was issued in 1968 by Harcourt Brace in the USA as well as by Longman’s in Canada. The positive critical response it generated assisted Engel in obtaining Canada Council funding; this allowed her some time to focus on her next book, which appeared in 1970 as The Honeyman Festival (originally titled The Silent Companions). Harcourt Brace, apparently the first house to which Engel

Hugh MacLennan, a well-established writer, and supervisor of Engel’s M.A. thesis (completed at McGill in 1957), provided early support and useful publishing contacts for her. On his recommendation the prestigious New York literary agents Russell and Volkening agreed to represent her work. Her first published novel, No Clouds of Glory (originally titled Sarah Bastard’s Notebook) was issued in 1968 by Harcourt Brace in the USA as well as by Longman’s in Canada. The positive critical response it generated assisted Engel in obtaining Canada Council funding; this allowed her some time to focus on her next book, which appeared in 1970 as The Honeyman Festival (originally titled The Silent Companions). Harcourt Brace, apparently the first house to which Engel  submitted the manuscript, rejected Honeyman, as did Macmillan of Canada, to whom she subsequently sent it, following an expression of interest from the company’s president, Hugh Kane. The novel, complete with descriptions of what Harcourt Brace editor Dan Wickenden called “the more disgusting aspects of infancy and of the domestic life in general,” (16 December 1968) eventually found a home with a fledgling Canadian publisher, House of Anansi, established in 1967 by David Godfrey and Dennis Lee in Toronto. Douglas Fetherling, its first full time employee, later observed that although many other small presses began around the same time, “Anansi was different. It was out to change writing by displacing the old generation with the new.” That new generation was represented in the Anansi list by Al Purdy, Michael Ondaatje, and Margaret Atwood, as well as Marian Engel.

submitted the manuscript, rejected Honeyman, as did Macmillan of Canada, to whom she subsequently sent it, following an expression of interest from the company’s president, Hugh Kane. The novel, complete with descriptions of what Harcourt Brace editor Dan Wickenden called “the more disgusting aspects of infancy and of the domestic life in general,” (16 December 1968) eventually found a home with a fledgling Canadian publisher, House of Anansi, established in 1967 by David Godfrey and Dennis Lee in Toronto. Douglas Fetherling, its first full time employee, later observed that although many other small presses began around the same time, “Anansi was different. It was out to change writing by displacing the old generation with the new.” That new generation was represented in the Anansi list by Al Purdy, Michael Ondaatje, and Margaret Atwood, as well as Marian Engel.

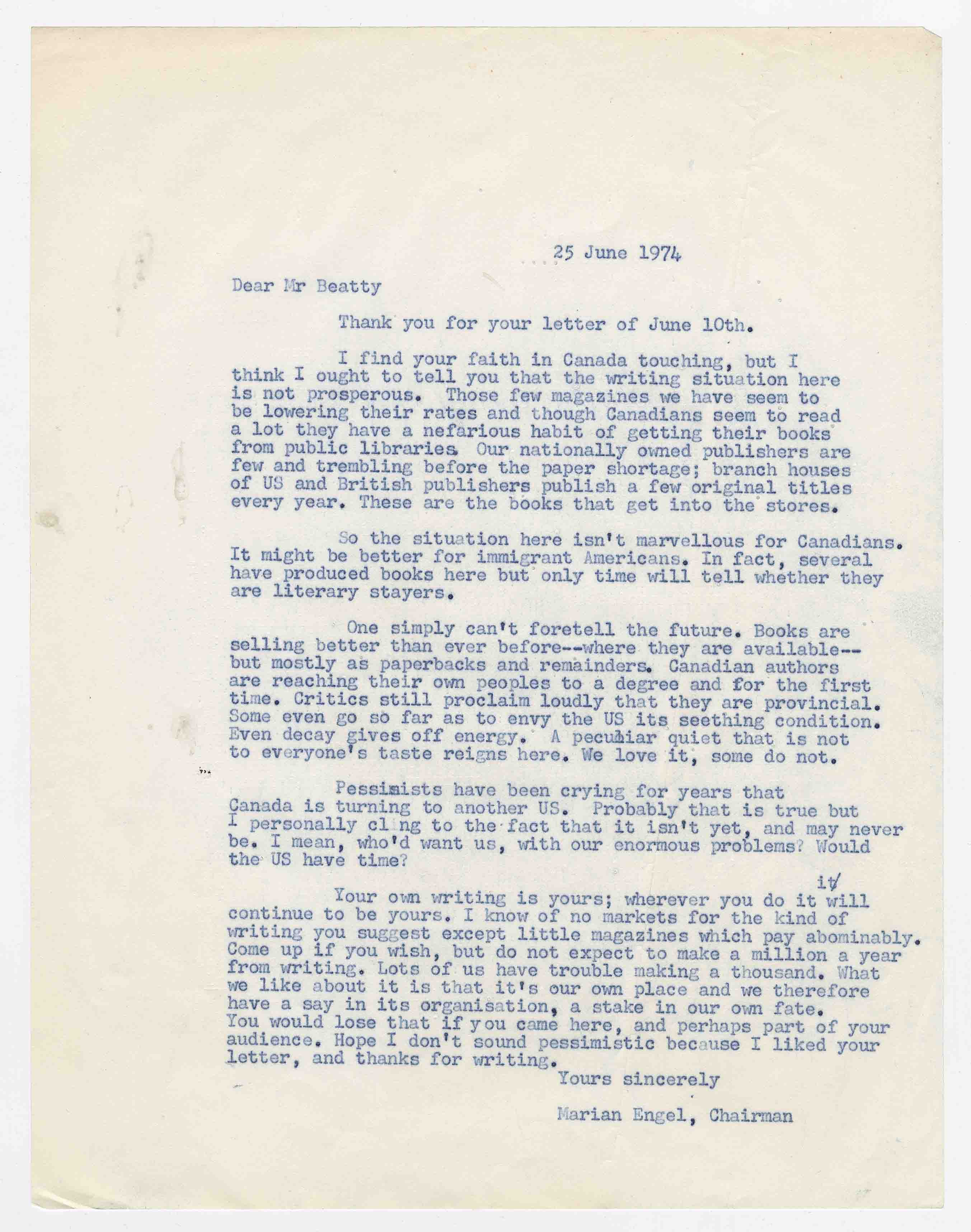

The House of Anansi was also to provide a home for Engel’s next two books, the novel Monodromos (1973) and her first collection of short stories, Inside the Easter Egg (1975). In 1973 Engel was elected first Chair of the newly established Writers’ Union of Canada; early meetings of the group took place in Engel’s living room and her correspondence reflects her increasing activism on behalf of Canadian writers, both nationally and internationally. Her complaint, in a letter to Robert Weaver on 8 March 1974 that “Publishers expect you to do everything but turn the crank on the press” must have reflected the discouragement of many writers of the period; she returned a much-needed cheque to Chatelaine magazine, protesting that “Nobody, not even housewives, should sell world

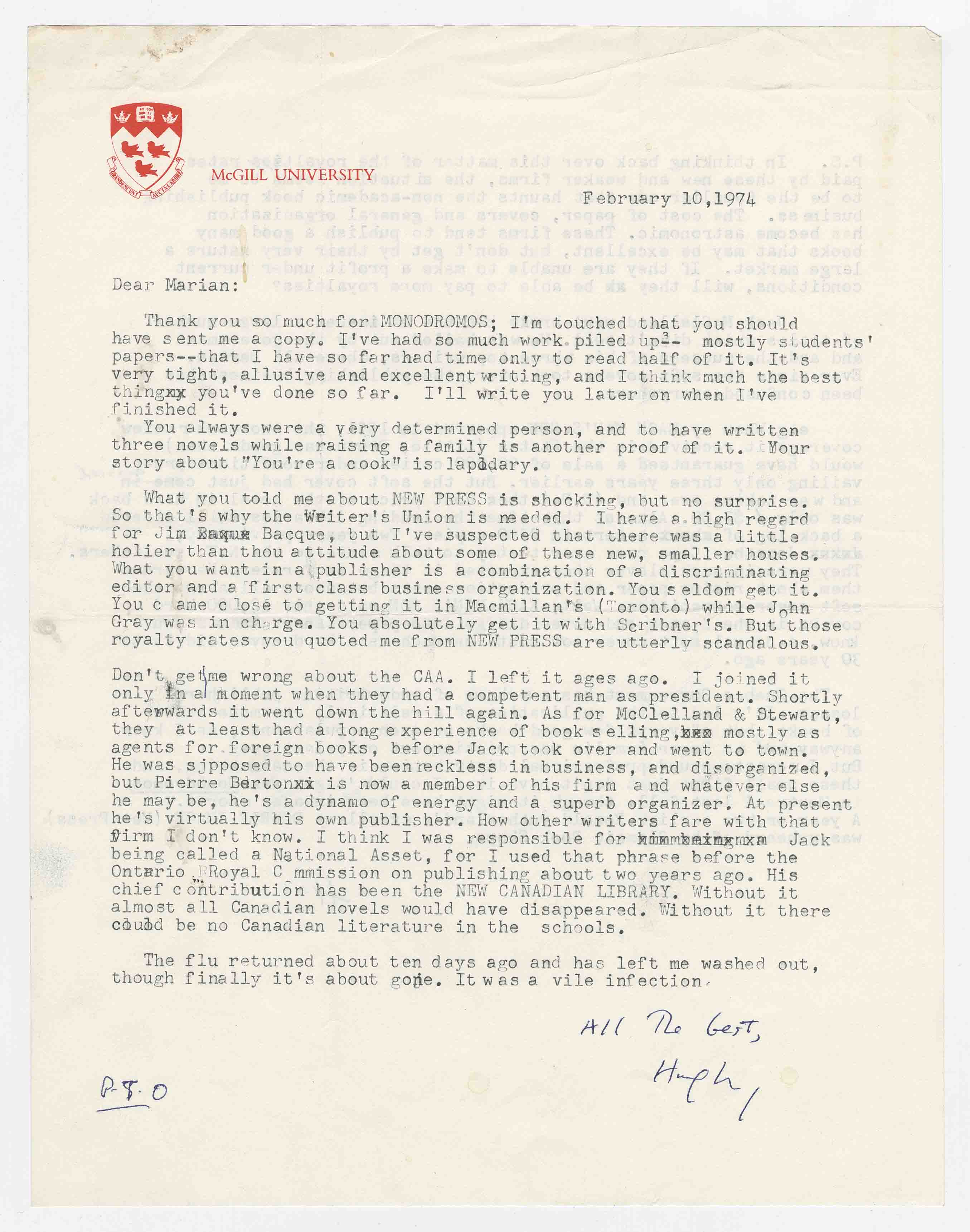

The House of Anansi was also to provide a home for Engel’s next two books, the novel Monodromos (1973) and her first collection of short stories, Inside the Easter Egg (1975). In 1973 Engel was elected first Chair of the newly established Writers’ Union of Canada; early meetings of the group took place in Engel’s living room and her correspondence reflects her increasing activism on behalf of Canadian writers, both nationally and internationally. Her complaint, in a letter to Robert Weaver on 8 March 1974 that “Publishers expect you to do everything but turn the crank on the press” must have reflected the discouragement of many writers of the period; she returned a much-needed cheque to Chatelaine magazine, protesting that “Nobody, not even housewives, should sell world  rights. And if you want French rights you should negotiate them with authors.” Sending him a copy of Monodromos, Engel attempted to persuade Hugh MacLennan to join the Writers’ Union, prompting a thoughtful response from him about the history and present state of Canadian publishing: “These firms tend to publish a good many books that may be excellent, but don’t get by their very nature a large market. If they are unable to make a profit under current conditions, will they be able to pay more royalties? Jack McClelland went broke because he issued a large number of titles which didn’t sell …”

rights. And if you want French rights you should negotiate them with authors.” Sending him a copy of Monodromos, Engel attempted to persuade Hugh MacLennan to join the Writers’ Union, prompting a thoughtful response from him about the history and present state of Canadian publishing: “These firms tend to publish a good many books that may be excellent, but don’t get by their very nature a large market. If they are unable to make a profit under current conditions, will they be able to pay more royalties? Jack McClelland went broke because he issued a large number of titles which didn’t sell …”

It was with Bear, the novel that was to become her best-known, that Engel entered the McClelland & Stewart (M&S) publishing orbit and began an  association with Jack McClelland that developed into a lively friendship, lasting until her death. On 7 November 1975, Dan Wickenden at Harcourt Brace had written with regret once again upon receipt of the manuscript: “Its relative brevity coupled with its extreme strangeness presents, I’m afraid, an insuperable obstacle in present circumstances.” However, McClelland reported that Robertson Davies had enthusiastically recommended publication of the novel, a story about a woman’s love affair with a bear. With the book’s publication by M&S in May 1976, Engel had “broken away from the one-horse, however lovely, publishers.” Bear won her a Governor General’s Award.

association with Jack McClelland that developed into a lively friendship, lasting until her death. On 7 November 1975, Dan Wickenden at Harcourt Brace had written with regret once again upon receipt of the manuscript: “Its relative brevity coupled with its extreme strangeness presents, I’m afraid, an insuperable obstacle in present circumstances.” However, McClelland reported that Robertson Davies had enthusiastically recommended publication of the novel, a story about a woman’s love affair with a bear. With the book’s publication by M&S in May 1976, Engel had “broken away from the one-horse, however lovely, publishers.” Bear won her a Governor General’s Award.

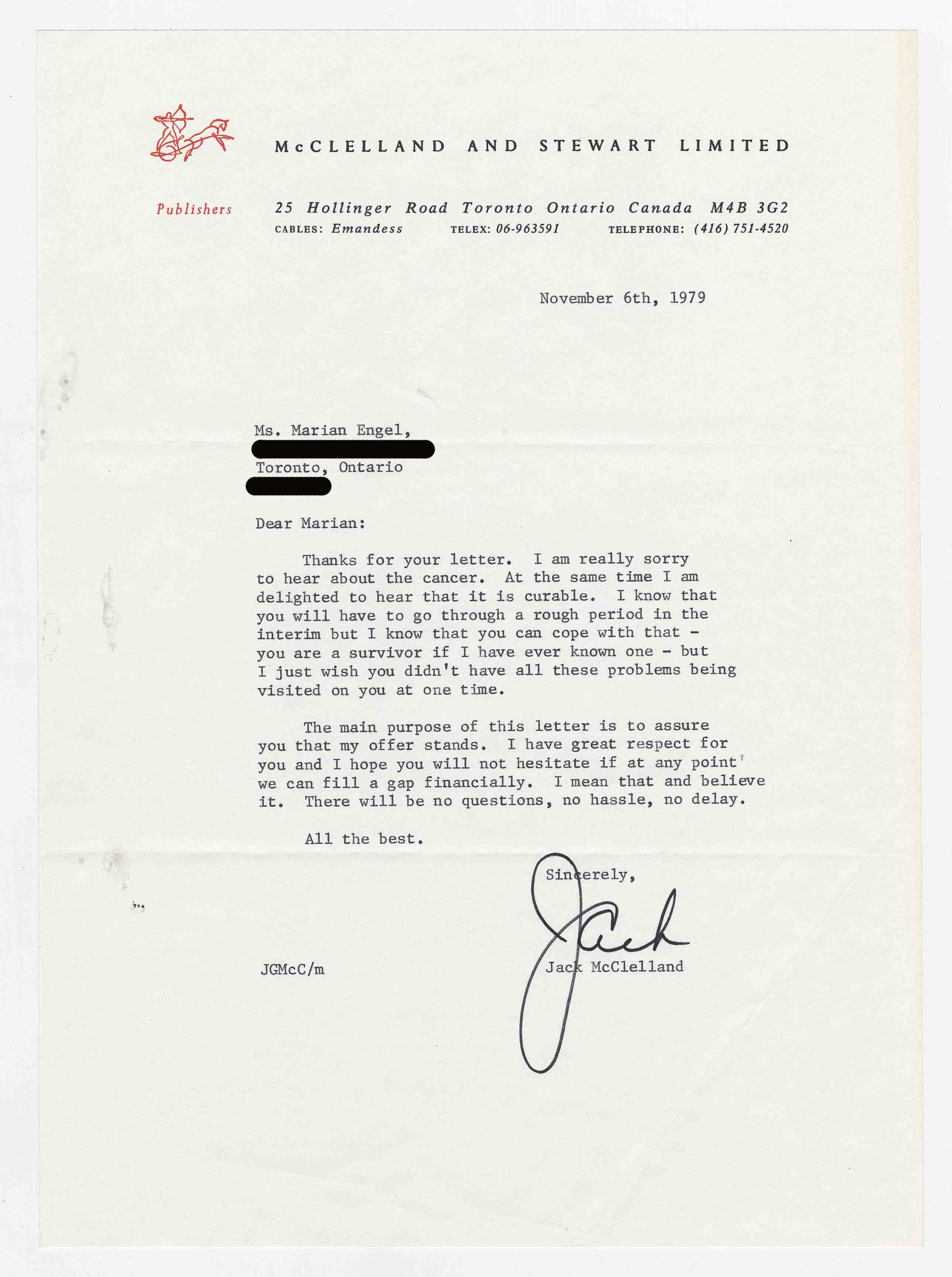

Following the immense success of Bear, it was inevitable that Engel’s next novel, The Glassy Sea (1978), would appear with M&S. However, it did not sell nearly as well, and the following year Engel was diagnosed with cancer. By now a single mother with teenage twins, Engel was in even more difficult financial circumstances than usual. Writing in November 1979, Jack McClelland demonstrated the qualities of empathy and generosity that endeared him to so many struggling Canadian writers: “I have great respect for you and I hope you will not hesitate if at any point we can fill a gap financially …. There will be no questions, no hassle, no delay.”

Following the immense success of Bear, it was inevitable that Engel’s next novel, The Glassy Sea (1978), would appear with M&S. However, it did not sell nearly as well, and the following year Engel was diagnosed with cancer. By now a single mother with teenage twins, Engel was in even more difficult financial circumstances than usual. Writing in November 1979, Jack McClelland demonstrated the qualities of empathy and generosity that endeared him to so many struggling Canadian writers: “I have great respect for you and I hope you will not hesitate if at any point we can fill a gap financially …. There will be no questions, no hassle, no delay.”

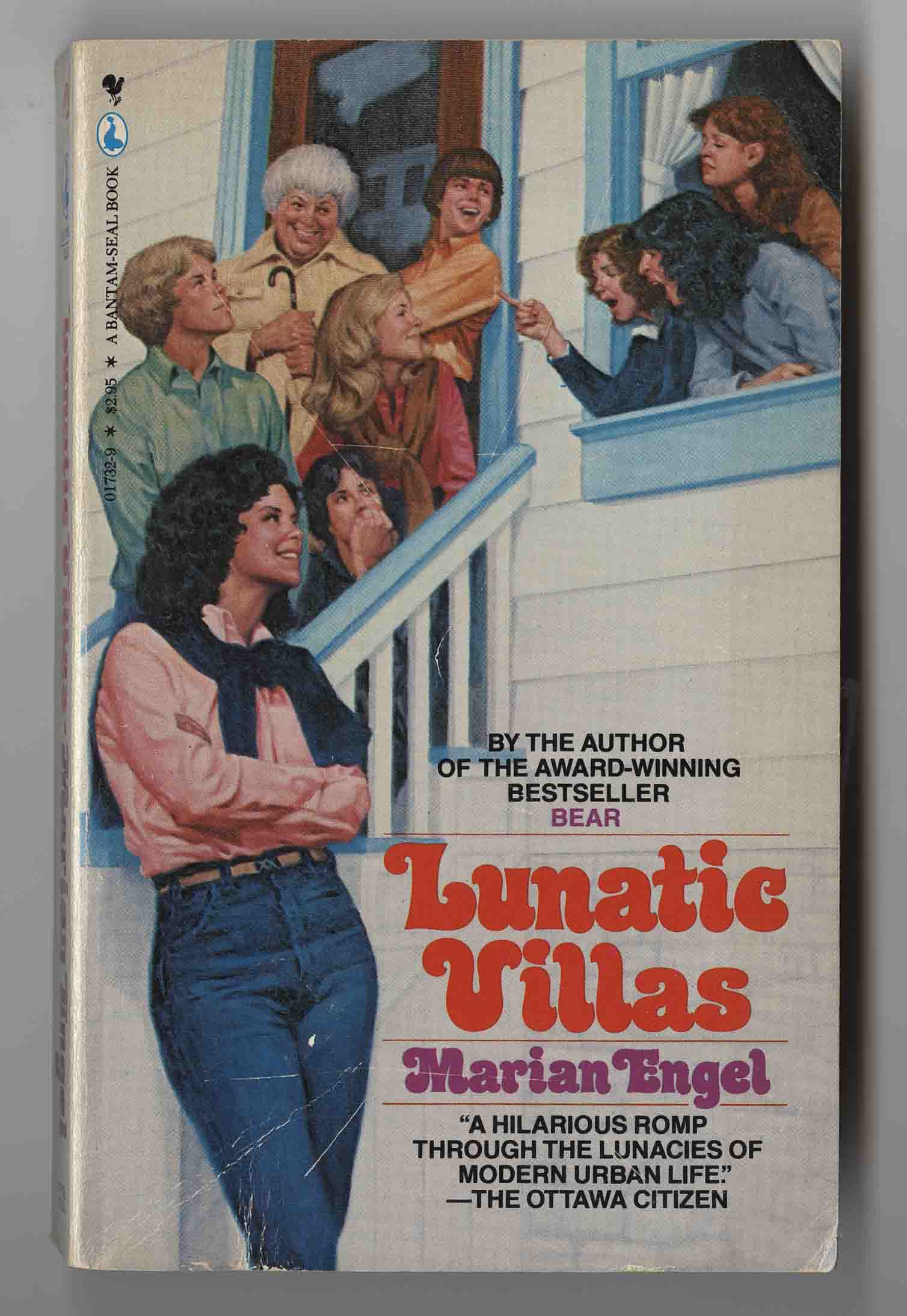

M&S published Engel’s last completed novel, Lunatic Villas, in 1981. In December of that year she wrote to McClelland that his “very generous advance” was a “lifesaver” – “I now understand why Canadians can’t have them [advances] unless they’re the Top Ten [i.e. the top ten best-selling Canadian authors] No way of earning them back.” But Engel remained as feisty as ever: “because I don’t make much money for either you or me, I’m from now on just going to plug along doing whatever I damn well please and hoping for the best.” Elizabeth and the Golden City, the “slow, wilful” novel on which she was working, remained unfinished. Engel died on 16 February 1985 at the age of 52.

M&S published Engel’s last completed novel, Lunatic Villas, in 1981. In December of that year she wrote to McClelland that his “very generous advance” was a “lifesaver” – “I now understand why Canadians can’t have them [advances] unless they’re the Top Ten [i.e. the top ten best-selling Canadian authors] No way of earning them back.” But Engel remained as feisty as ever: “because I don’t make much money for either you or me, I’m from now on just going to plug along doing whatever I damn well please and hoping for the best.” Elizabeth and the Golden City, the “slow, wilful” novel on which she was working, remained unfinished. Engel died on 16 February 1985 at the age of 52.

Fetherling, Douglas. Travels by Night: A Memoir of the Sixties. Toronto: McArthur & Co., 1994, 109

Verduyn, Christl and Kathy Garay, eds. Marian Engel: A Life in Letters. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Writers’ Union of Canada fonds, McMaster University

Marian Engel fonds, McMaster University