The Censorship of Margaret Laurence’s The Diviners, 1976-1985

Sheila Turcon, McMaster University

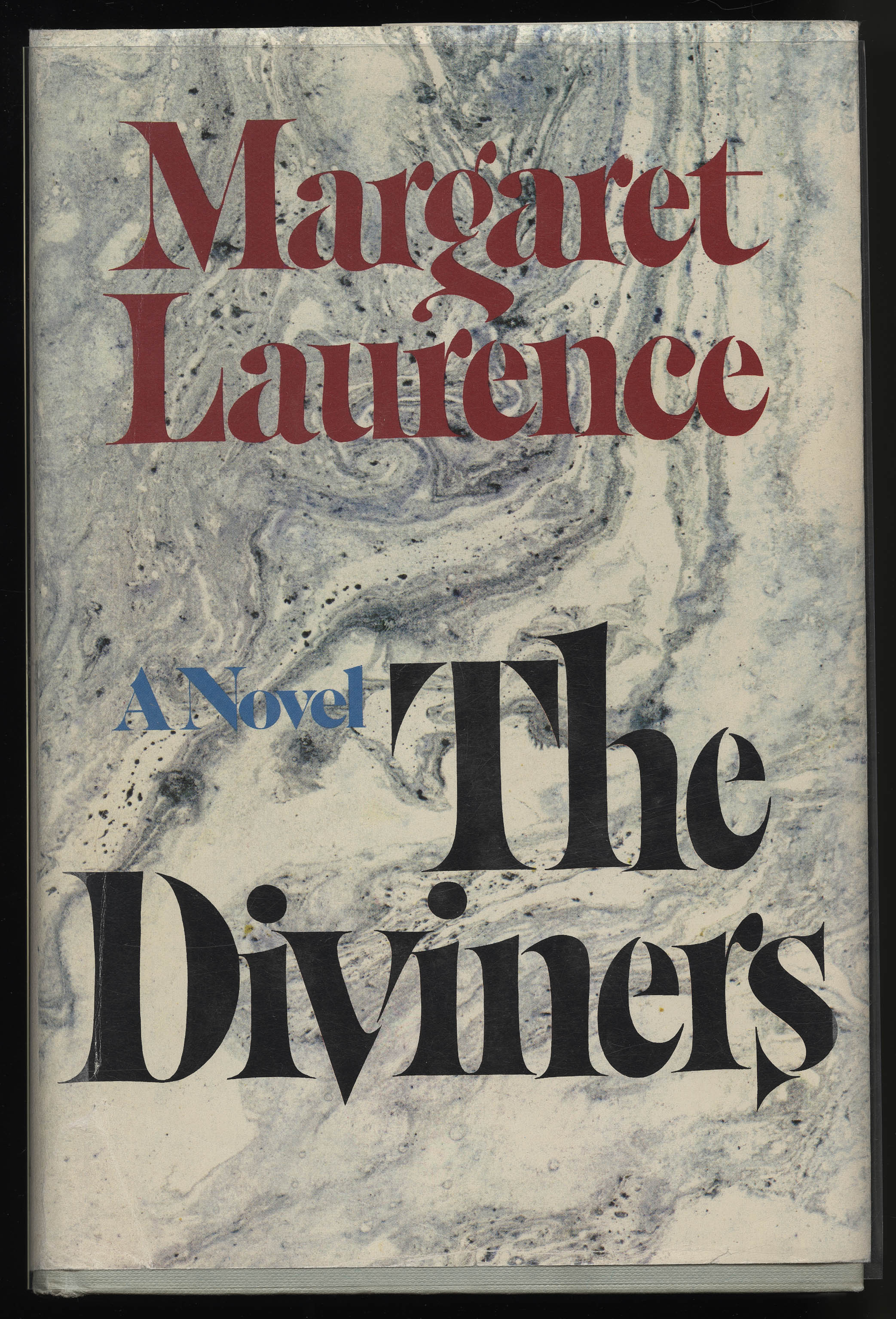

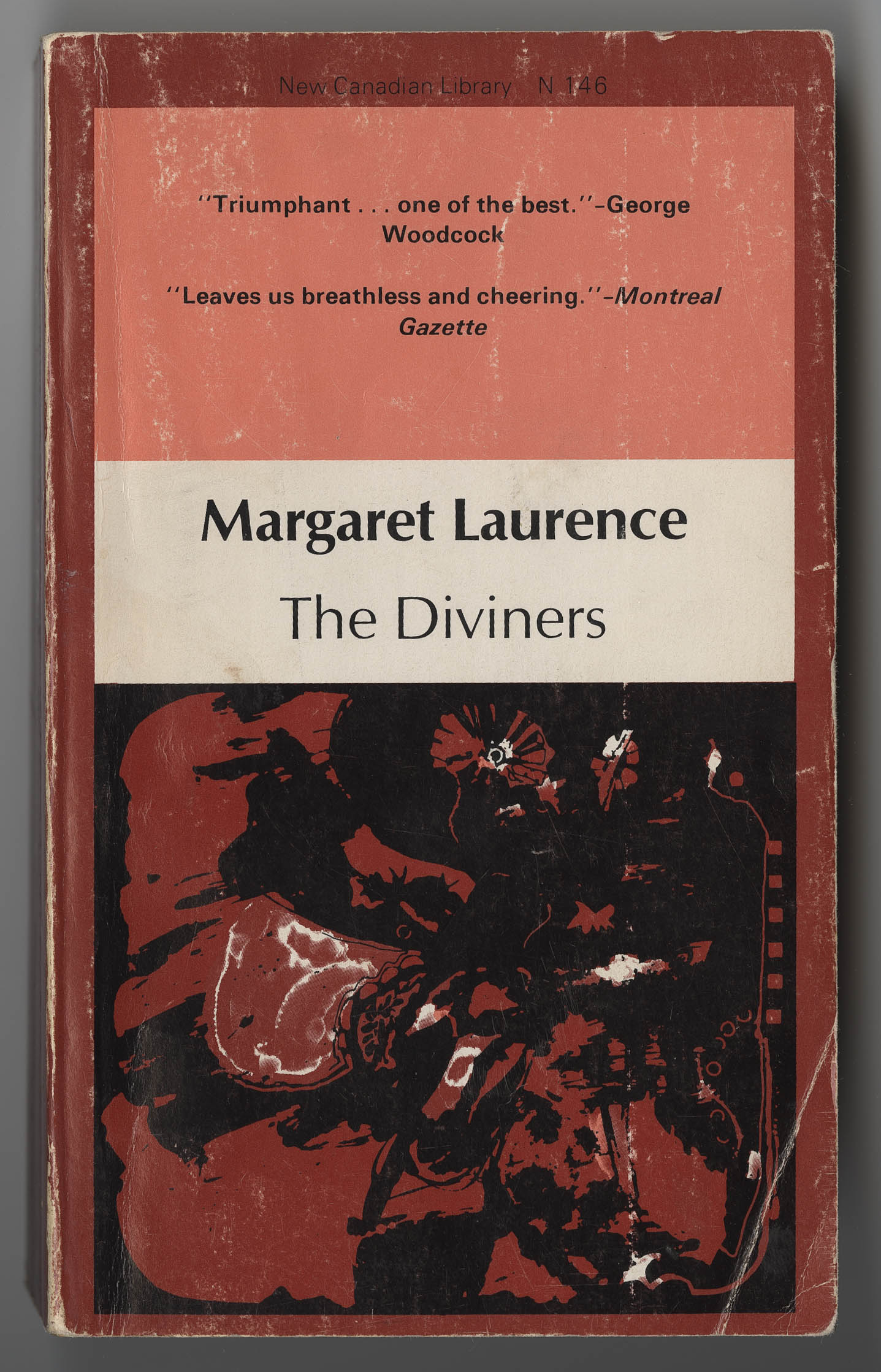

Set in the Prairie town of Manawaka, The Diviners tells the epic story of Morag Gunn. A writer, Gunn experiences difficult relationships with both her lover and her daughter. The novel deals with issues of race, sexuality, class, poverty, and abortion, and contains strong language in keeping with the characters it portrays. On a larger scale, the novel’s tone is profoundly spiritual and life-affirming.

Laurence was living in Lakefield near Peterborough, Ontario when the first controversy erupted. In 1968 the Ontario Ministry of Education had given local school boards the authority to determine which literary works would be used in  English classes. In the winter of 1976 complaints were lodged at two Peterborough high schools against both The Diviners and Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women (1971). Both books should have been reviewed by a special committee which had been established two years earlier to review complaints against other books. However, only Laurence’s book was dealt with by the committee. The book had been opposed by Jim Telford, a board of education trustee and member of the Pentecostal community, and Rev. Sam Buick. They and their supporters told the Globe and Mail that the novel “reeked of sordidness.” The review committee did not agree and gave its unanimous support for the retention of The Diviners. On 22 April 1976, the full board decided ten votes to six to keep the book on its approved textbook list. Despite this ruling, only Bob Buchanan from Lakefield Secondary School continued to teach it.

English classes. In the winter of 1976 complaints were lodged at two Peterborough high schools against both The Diviners and Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women (1971). Both books should have been reviewed by a special committee which had been established two years earlier to review complaints against other books. However, only Laurence’s book was dealt with by the committee. The book had been opposed by Jim Telford, a board of education trustee and member of the Pentecostal community, and Rev. Sam Buick. They and their supporters told the Globe and Mail that the novel “reeked of sordidness.” The review committee did not agree and gave its unanimous support for the retention of The Diviners. On 22 April 1976, the full board decided ten votes to six to keep the book on its approved textbook list. Despite this ruling, only Bob Buchanan from Lakefield Secondary School continued to teach it.

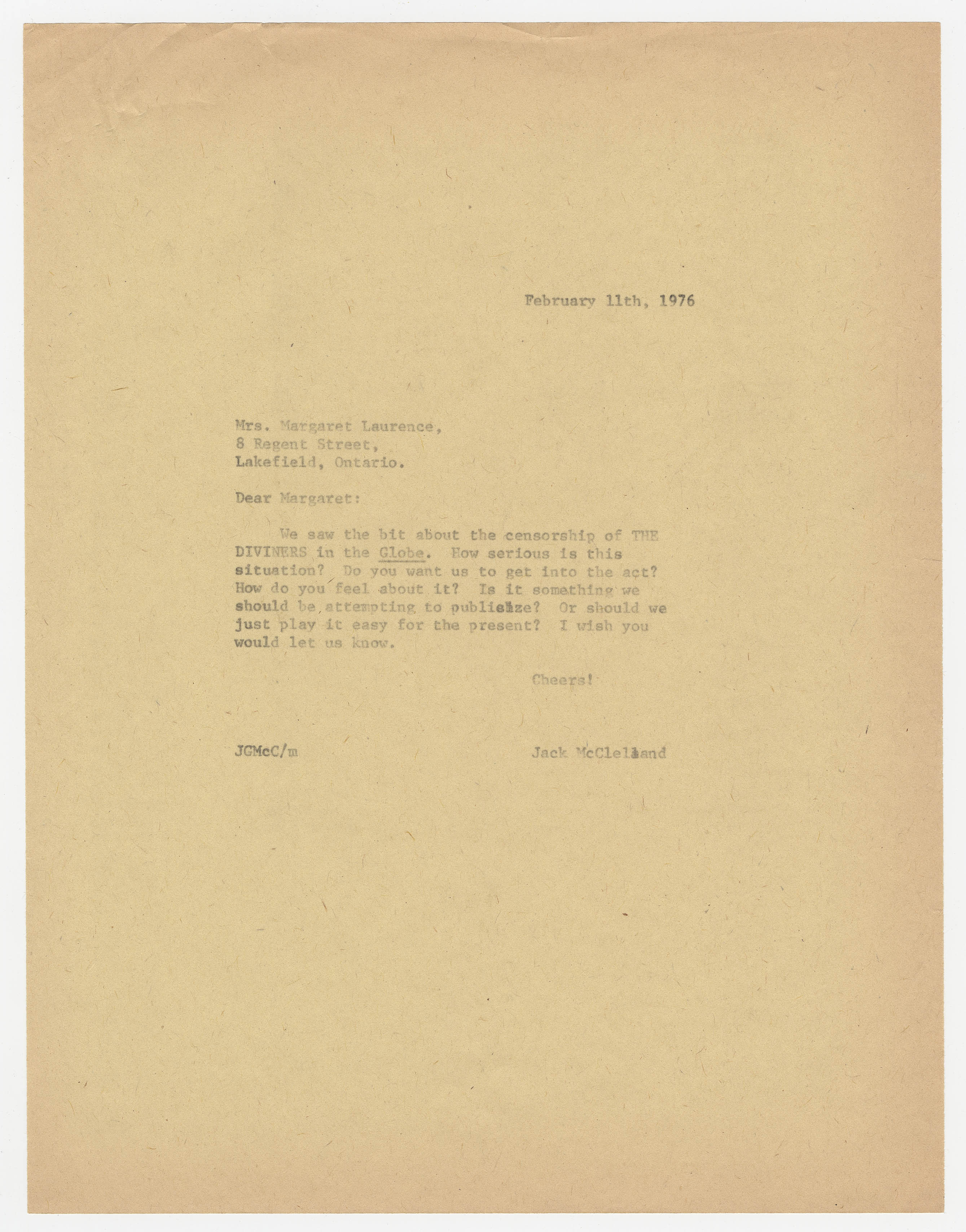

Laurence’s publisher, Jack McClelland of McClelland & Stewart (M&S), supported her through this ordeal. He wrote her on 11 February 1976, asking how serious the matter was, what her feelings were, and what he should do about the situation. She replied that there had been “several very nasty letters in the Globe [and Mail], saying, in effect, that The Diviners is ‘loaded with vulgar language’ and ‘disgusting’ sex scenes. It would be awfully nice if someone could write a few letters simply in support of the merits of the novel itself.” She went on to say: “All phone calls have been supportive, so far. I got one anonymous nasty letter from someone in Peterborough, grouping me with Jacqueline Susann and Xaviera Hollander … it’s a bit odd to have this happening in my own Village. I’d feel worse if it were Neepawa, Man. tho.” On 17 February, McClelland agreed to get some letters organized and sent to the press. He noted that he had been speaking to English teachers in Ottawa, who agreed to send a telegram of support to the Globe and Mail.

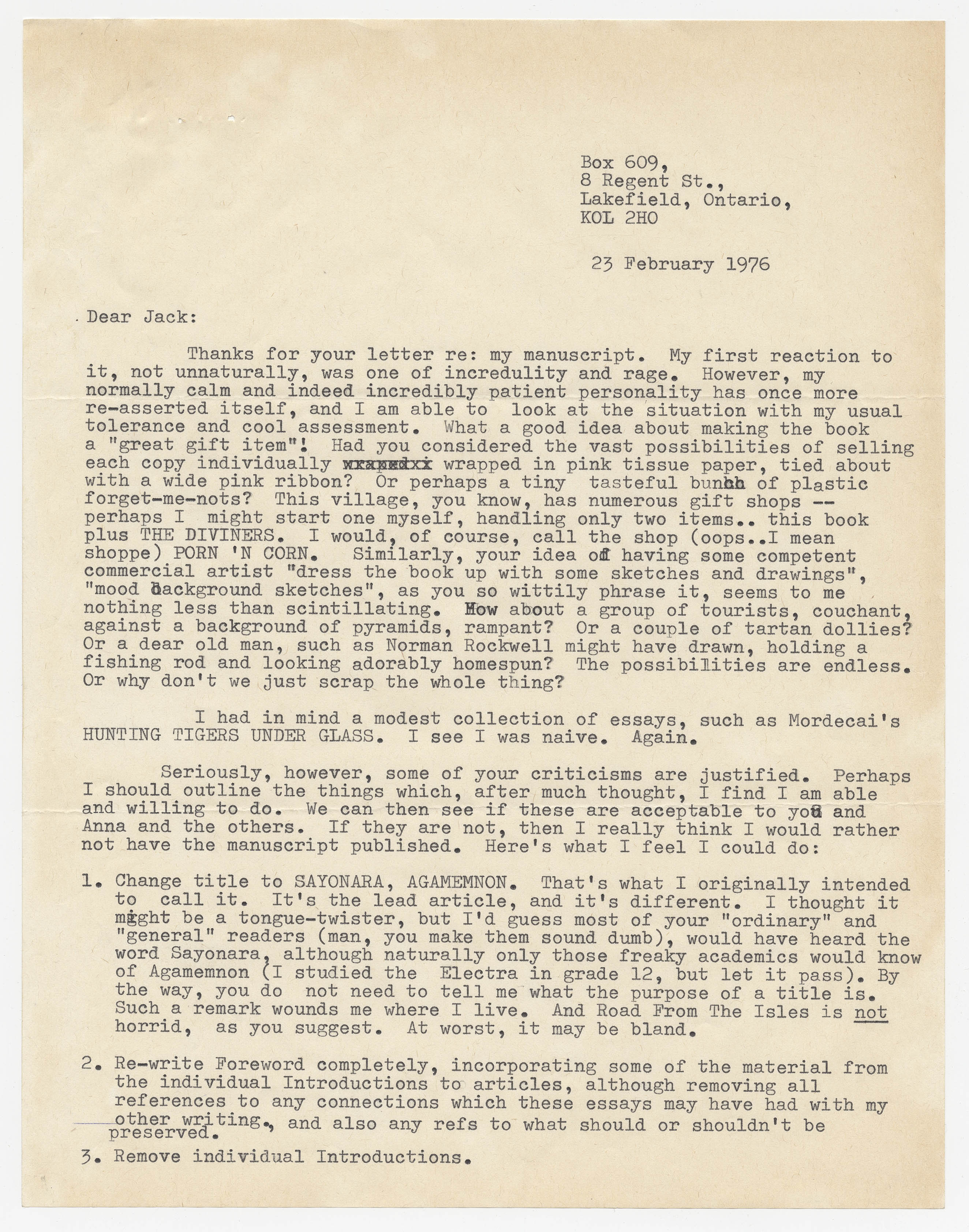

Laurence’s publisher, Jack McClelland of McClelland & Stewart (M&S), supported her through this ordeal. He wrote her on 11 February 1976, asking how serious the matter was, what her feelings were, and what he should do about the situation. She replied that there had been “several very nasty letters in the Globe [and Mail], saying, in effect, that The Diviners is ‘loaded with vulgar language’ and ‘disgusting’ sex scenes. It would be awfully nice if someone could write a few letters simply in support of the merits of the novel itself.” She went on to say: “All phone calls have been supportive, so far. I got one anonymous nasty letter from someone in Peterborough, grouping me with Jacqueline Susann and Xaviera Hollander … it’s a bit odd to have this happening in my own Village. I’d feel worse if it were Neepawa, Man. tho.” On 17 February, McClelland agreed to get some letters organized and sent to the press. He noted that he had been speaking to English teachers in Ottawa, who agreed to send a telegram of support to the Globe and Mail.  In the same letter McClelland attempted to cheer her up with a mock scolding: “The only sensible conclusion I can reach, Margaret, is that you have simply got to stop writing these dirty, vulgar books. It offends my sensibilities.” To his other suggestion that they make the book a “great gift item” she responded on 23 February: “This village, you know, has numerous gift shops – perhaps I might start one myself, handling only two items[:] this book [Heart of a Stranger] and THE DIVINERS. I would, of course, call the shop (oops..I mean shoppe) PORN ‘N CORN.” But she closed more seriously, thanking him for his offer to help.

In the same letter McClelland attempted to cheer her up with a mock scolding: “The only sensible conclusion I can reach, Margaret, is that you have simply got to stop writing these dirty, vulgar books. It offends my sensibilities.” To his other suggestion that they make the book a “great gift item” she responded on 23 February: “This village, you know, has numerous gift shops – perhaps I might start one myself, handling only two items[:] this book [Heart of a Stranger] and THE DIVINERS. I would, of course, call the shop (oops..I mean shoppe) PORN ‘N CORN.” But she closed more seriously, thanking him for his offer to help.

The opponents of The Diviners were not willing to let the issue die. Rev. Buick organized a petition to demand that the Board re-open the debate – 4,000 people signed it. By the fall Buick had organized a slate of  three candidates to stand for election. He had also gone outside the community for support, gaining the backing of Rev. Ken Campbell of Milton, Ontario who headed a group called “Renaissance Canada.” While all three candidates went down to defeat, including trustee Jim Telford, Renaissance would remain as the prime mover behind most attempts to ban The Diviners for the next nine years.

three candidates to stand for election. He had also gone outside the community for support, gaining the backing of Rev. Ken Campbell of Milton, Ontario who headed a group called “Renaissance Canada.” While all three candidates went down to defeat, including trustee Jim Telford, Renaissance would remain as the prime mover behind most attempts to ban The Diviners for the next nine years.

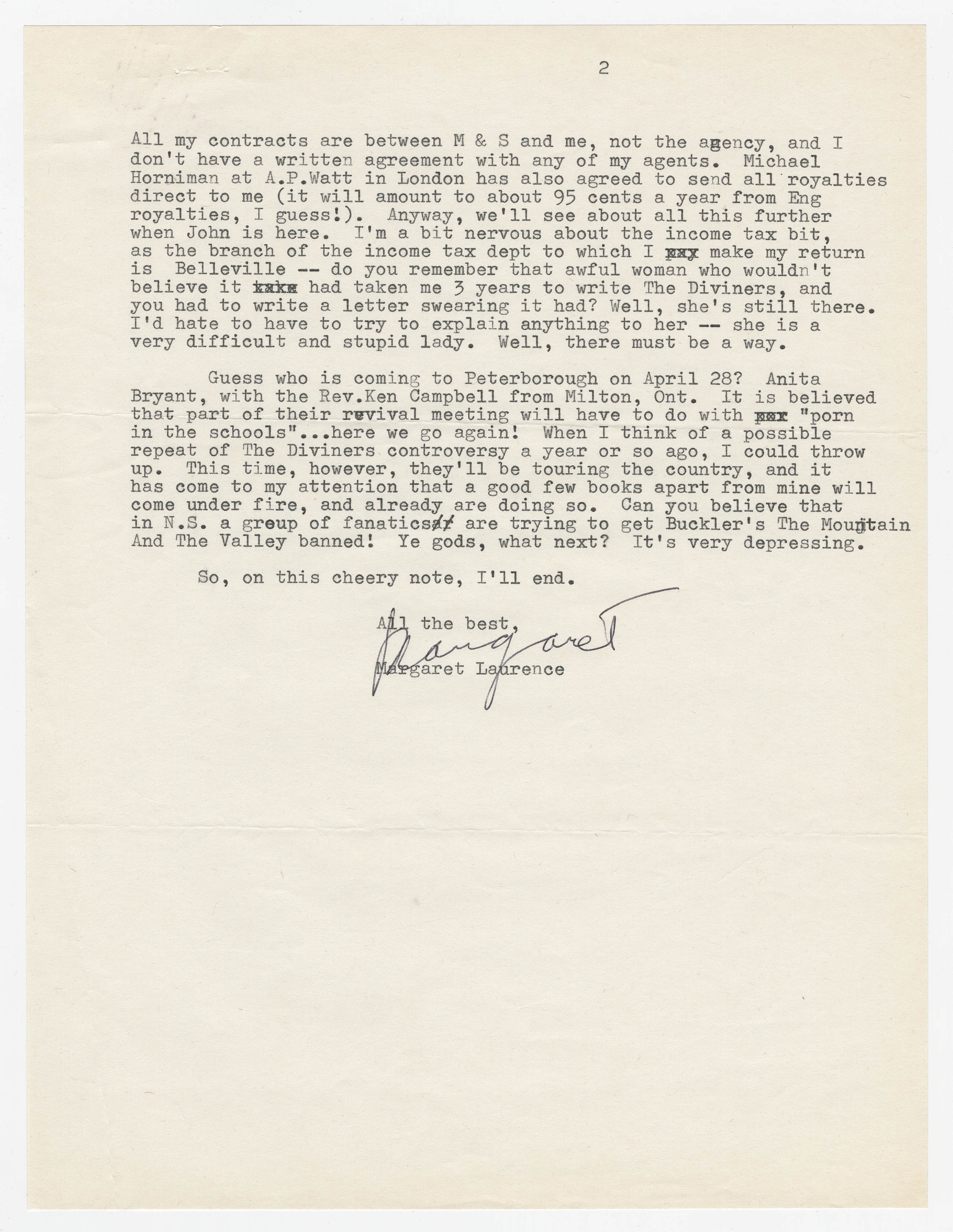

Two years later, Laurence wrote to McClelland: “Guess who is coming to Peterborough on April 28? Anita Bryant [American singer; gay rights opponent], with The Rev. Ken Campbell … It is believed that part of their revival meeting will have to do with ‘porn in the schools’ … When I  think of a possible repeat of the Diviners controversy a year or so ago, I could throw up”. Still trying to keep things light-hearted, McClelland responded on 17 April: “That sounds great about Anita Bryant’s visit. We must stamp out these dirty books. I am all for encouraging these people because it sells more books.”

think of a possible repeat of the Diviners controversy a year or so ago, I could throw up”. Still trying to keep things light-hearted, McClelland responded on 17 April: “That sounds great about Anita Bryant’s visit. We must stamp out these dirty books. I am all for encouraging these people because it sells more books.”

By the summer of 1978, parent groups organized by Renaissance successfully pressured the Huron County School Board in Ontario to consider removing The Diviners as well as two other books from school curricula. Although this censorship was condemned in the pages of the Globe and Mail by renowned book critic William French, the Board voted on 21 August to remove The Diviners from all five high schools in the county. This case was pivotal because it was the first time Renaissance had successfully pressured a school board into removing a title from its approved list of textbooks. At the same time, the case galvanized those opposed to this censorship. The Writers’ Union of Canada, the Canadian Library Association, The Canadian Booksellers Association, and the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation all formed lobbying committees and developed policies to combat censorship. The Book and Periodical Council formed a group called “The Freedom of Expression Committee” which would go on to launch Freedom to Read Week in 1984. In the midst of the 1978 controversy, a gala fundraiser was held by the Freedom of Expression Committee. Margaret Laurence was given a standing ovation when she took to the stage to read from The Diviners.

Somewhat lost in all this sound and fury was the fact that the stated policy of the Ontario Education Act was to promote Judeo-Christian values. Opponents of The Diviners and other books felt they were on sound legal as well as moral ground in attempting to remove books from the curriculum. In 1985 a second attempt was made to have The Diviners banned in Peterbororough. This time Laurence did not remain in the background – she vigorously defended her book. Possibly she and McClelland exchanged thoughts on this latest incident but their correspondence is not extant in archival records at McMaster University Library. McClelland, however, did reflect in his incomplete memoir which is housed in his papers at McMaster : “I am reminded of the agony and disquiet that this deeply caring, deeply moral and dedicated woman suffered as a result of concerted attacks by mindless, self-appointed censors in Lakefield and Peterborough County, who attempted to have her works removed from school and library shelves. It was an outrage. It was an experience that hurt her deeply but one which she fought eloquently with grace and conviction.”

Freedom to Read Week continues as a lobby organization and support network for writers, publishers, and librarians. The group publishes an annual report that details the history of every publication in Canada subject to a censorship challenge. In its latest report, it was noted that after nearly twenty years of challenges, The Diviners no longer appears in the curriculum of at least two Canadian provinces. Another consequence of the controversy was the establishment of protocols for handling censorships challenges. Among writers, publishers, and booksellers came the realization that censorship campaigns must not be dismissed as the workings of a lunatic fringe. Rev. Campbell turned his attention to pro-life campaigns in the 1980s and at the time of his death in 2006 was most remembered for his demonstrations against the Morgentaler abortion clinic in Toronto.

The toll on Laurence herself was heavy. She died just over a year following the second attempt to ban her book. Writer Timothy Findley observed: “no other writer in Canadian history suffered more at the hands of these professional naysayers, book-banners and censors than Laurence.” She had a strong Christian faith and was deeply wounded by the suggestion that she and her novels lacked a strong moral core. She was never able to finish her novel of a small town teacher’s battle with fundamentalist Christians. Instead her epithet, perhaps fittingly so, is her last novel, The Diviners.

*This study is based on research completed by Tracey Warren for an unpublished paper written for graduate coursework in history at McMaster University, and is used with her kind permission.

Ayre, John. “Bell, Book and Scandal: Margaret Laurence’s Book Went to High School and Now the Preacher Wants it Expelled.” Globe and Mail, 28 August 1976.

Birdsal, Peter and Delores Broten. Mind Wars: Censorship in English Canada. CANLIT Publications: Victoria BC, 1978.

Findley, Timothy. “A Life of Eloquence and Radicalism.” Maclean’s Magazine, 18 January 1987.

King, James. The Life of Margaret Laurence. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1998.

“Laurence’s Book Banned.” CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) Digital Archives. Broadcast date: 25 January 1985: http://archives.cbc.ca/arts_entertainment/literature/topics/161/

“Laurence Speaks Out Against Censorship.” CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) Digital Archives. Broadcast date: 25 January 1985: http://archives.cbc.ca/arts_entertainment/literature/topics/161/

Powers, Lyall. Alien Heart: The Life and Work of Margaret Laurence. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2005.

Woodcock, George, ed. A Place To Stand On: Essays By and About Margaret Laurence. Edmonton: NeWest Press, 1983.

Marian Engel fonds, McMaster University

Writers’ Union of Canada fonds, McMaster University

Jack McClelland fonds, McMaster University

Margaret Laurence fonds, McMaster University