J.W. Bengough: Publisher and Pioneer of Editorial Cartooning in English Canada

Christopher Ernst, University of Toronto

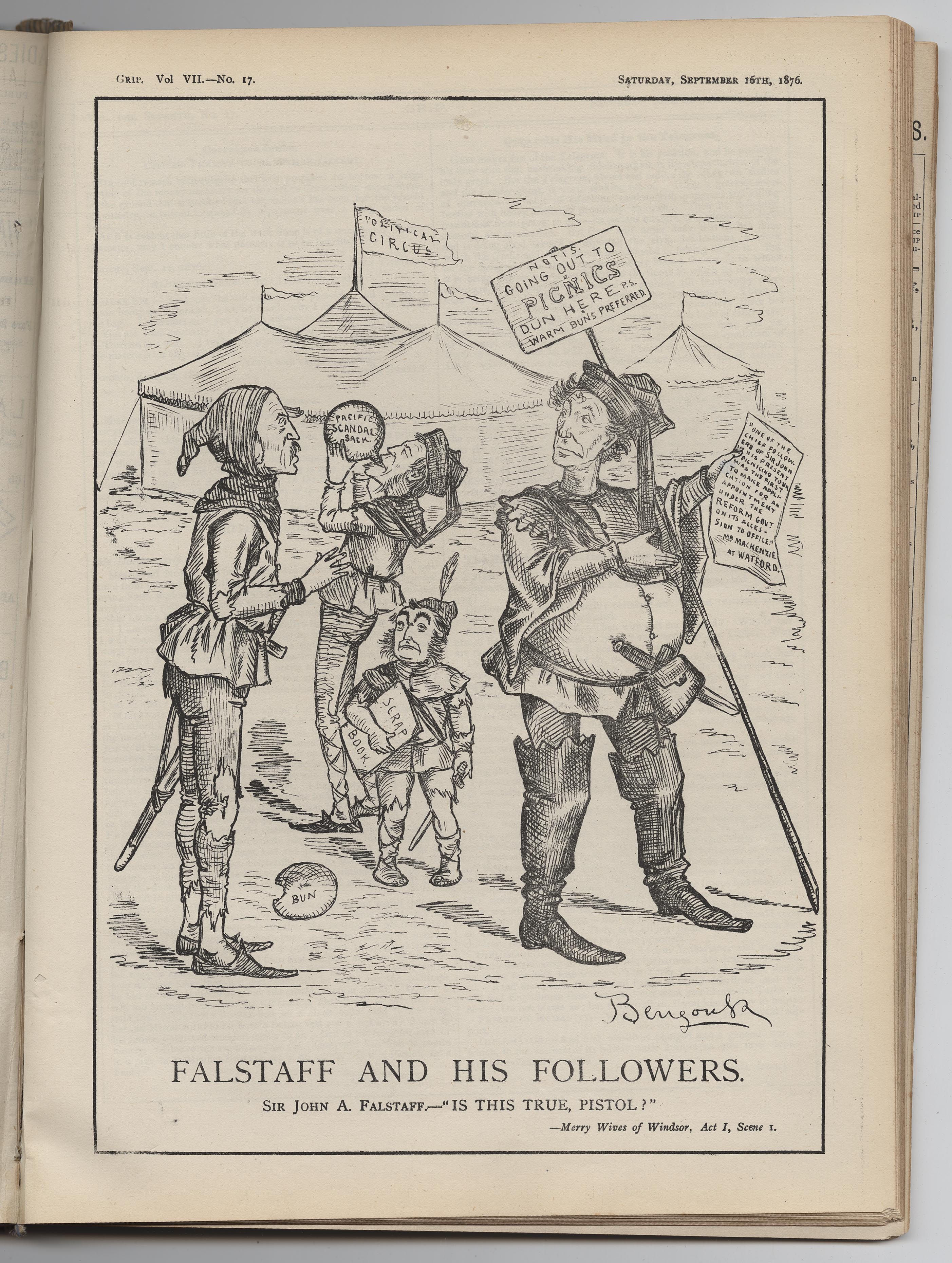

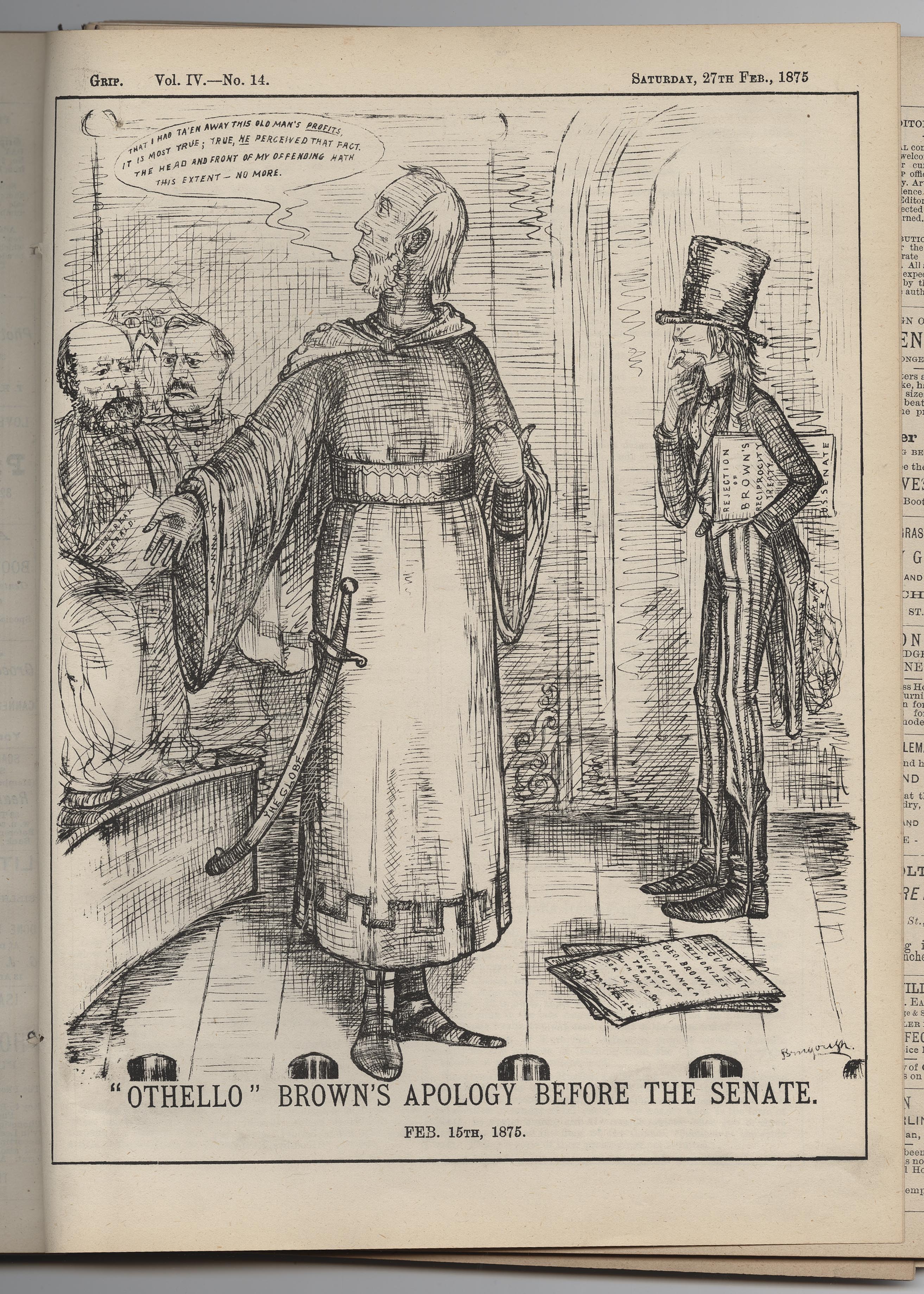

John Wilson Bengough (1851-1923) is best known for his work as the editor and chief cartoonist of the satiric magazine Grip. Less well-known are his efforts as a publisher, poet, playwright, lecturer, social crusader, politician, and would-be screenwriter. His politics and his publishing were closely connected; both were inseparable from his religious worldview. As a Christian reformer, Bengough was a vocal advocate for such causes as temperance, women’s suffrage, and workers’ rights. Indeed, his concern with issues of class led him to embrace the teachings of the American social critic Henry George—especially the concepts of a single tax and free trade. In theory, Bengough favoured a republican style of government with close connections to other so-called “Anglo-Saxon” nations. Despite his radical  leanings, he was a supporter of the Liberal party. Bengough used his magazine and the publishing company which evolved from the periodical, to advance his social and political thought. Indeed, the breaking of the Pacific Scandal in 1873, centering on Sir John A. Macdonald’s financial corruption, gave Grip fodder for its early days. Many, including Bengough himself, attributed the magazine’s success to the timing of the controversy. From then on, Macdonald and his Tory government became regular targets of Grip’s sly humour and frequent vitriol.

leanings, he was a supporter of the Liberal party. Bengough used his magazine and the publishing company which evolved from the periodical, to advance his social and political thought. Indeed, the breaking of the Pacific Scandal in 1873, centering on Sir John A. Macdonald’s financial corruption, gave Grip fodder for its early days. Many, including Bengough himself, attributed the magazine’s success to the timing of the controversy. From then on, Macdonald and his Tory government became regular targets of Grip’s sly humour and frequent vitriol.

Bengough and Grip, founded in 1873, offer a unique entry point into the socio-cultural and political life of late Victorian English Canada. Those who write about Bengough tend to be either journalists or academic historians, bringing with them the concerns and methodologies of their respective professions. The journalist and scholar Peter Desbarats, in conjunction with the political cartoonist Terry Mosher, offer non-specialist readers a thoughtful introduction to the subject. In their hands, Bengough is given credit as a founding father of English Canadian political cartooning. Ramsay Cook, the well-known Canadian historian, uses Bengough as a case study to advance his thesis regarding an expanding secularization in late Victorian culture. The Toronto satirist, avers Cook, was a telling example of a shift in Christianity from its traditional concern with mankind’s salvation to a commitment to social regeneration through the Social Gospel. As Director of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster University, which houses the largest collection of Bengough materials, Carl Spadoni introduces readers to the publishing and printing aspects of Bengough and his brothers. While most authors use Bengough as one part of a larger argument, Carman Cumming is

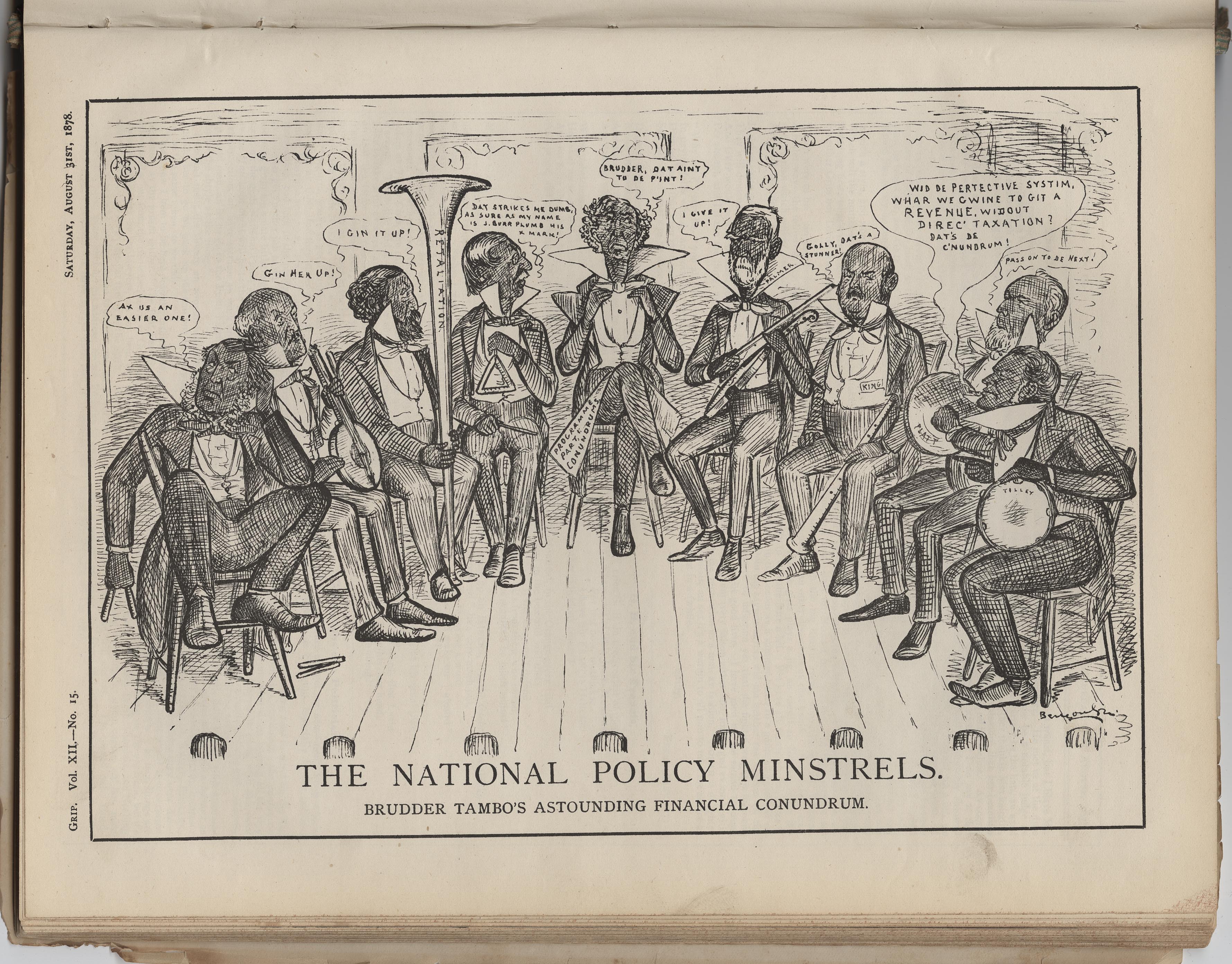

bringing with them the concerns and methodologies of their respective professions. The journalist and scholar Peter Desbarats, in conjunction with the political cartoonist Terry Mosher, offer non-specialist readers a thoughtful introduction to the subject. In their hands, Bengough is given credit as a founding father of English Canadian political cartooning. Ramsay Cook, the well-known Canadian historian, uses Bengough as a case study to advance his thesis regarding an expanding secularization in late Victorian culture. The Toronto satirist, avers Cook, was a telling example of a shift in Christianity from its traditional concern with mankind’s salvation to a commitment to social regeneration through the Social Gospel. As Director of Archives and Research Collections at McMaster University, which houses the largest collection of Bengough materials, Carl Spadoni introduces readers to the publishing and printing aspects of Bengough and his brothers. While most authors use Bengough as one part of a larger argument, Carman Cumming is  the only one so far to produce a book-length treatment entirely devoted to the artist’s cartoons. A professor of journalism, Cumming offers a traditional approach to Bengough’s work focusing on such concerns as politics, race, religion, the press, imperialism and social reform. More recently, historians have approached the artist and his magazine from a variety of vantage points reflecting the preoccupations of social and cultural history. Christina Burr explores Bengough’s gendered conception of nationalism. G. Bruce Retallack offers an insightful reading of gender and race in Bengough’s images as part of a larger discussion of the graphic codes of shaming involved in editorial cartooning. Finally, Alan Mendelson argues that Bengough and Grip helped make anti-Semitism more respectable in nineteenth-century English Canada.

the only one so far to produce a book-length treatment entirely devoted to the artist’s cartoons. A professor of journalism, Cumming offers a traditional approach to Bengough’s work focusing on such concerns as politics, race, religion, the press, imperialism and social reform. More recently, historians have approached the artist and his magazine from a variety of vantage points reflecting the preoccupations of social and cultural history. Christina Burr explores Bengough’s gendered conception of nationalism. G. Bruce Retallack offers an insightful reading of gender and race in Bengough’s images as part of a larger discussion of the graphic codes of shaming involved in editorial cartooning. Finally, Alan Mendelson argues that Bengough and Grip helped make anti-Semitism more respectable in nineteenth-century English Canada.

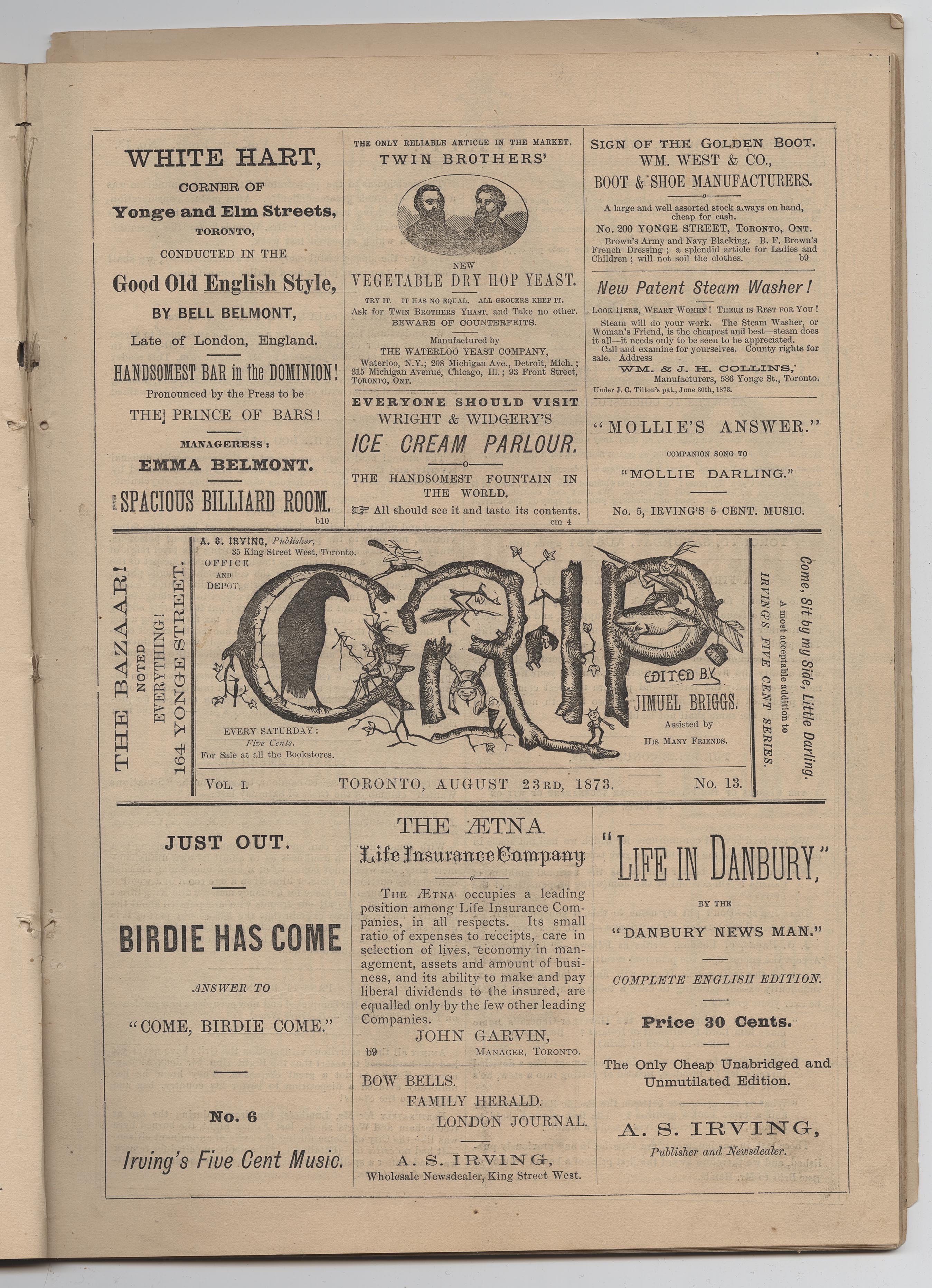

Although Bengough’s life and work have been studied by numerous scholars, few have focused exclusively on his role as a publisher. Grip, it is important to recognize, offered a venue for both amateur and professional writers. As most pieces in the magazine were published anonymously, it is difficult to attribute authorship. Nevertheless, Bengough accepted poetry, drama, and prose from a diverse group of authors. Writers such as T. Phillips Thompson, R.W. Phipps, Tom Boylan, Edward Edwards, Mrs. J K. Lawson, George Orran, Fred Swire, Charles G.D. Roberts, Peter McArthur, Alexander McLachlan, and Stephen Leacock each contributed to the pages of Grip. Bengough often included plays, dramatic dialogues, as well as metaphors and cartoons drawn from a dizzying array of public entertainments which were expanding rapidly in the late nineteenth century. Minstrel shows, circuses, melodrama, and Shakespearean allusions made regular appearances in Grip. In keeping with the editor’s passion for the theatre, especially plays espousing a reform-oriented politics, Grip published The Sweet Girl Graduate (1882) by Sarah Anne Curzon. The closet drama takes up the

Although Bengough’s life and work have been studied by numerous scholars, few have focused exclusively on his role as a publisher. Grip, it is important to recognize, offered a venue for both amateur and professional writers. As most pieces in the magazine were published anonymously, it is difficult to attribute authorship. Nevertheless, Bengough accepted poetry, drama, and prose from a diverse group of authors. Writers such as T. Phillips Thompson, R.W. Phipps, Tom Boylan, Edward Edwards, Mrs. J K. Lawson, George Orran, Fred Swire, Charles G.D. Roberts, Peter McArthur, Alexander McLachlan, and Stephen Leacock each contributed to the pages of Grip. Bengough often included plays, dramatic dialogues, as well as metaphors and cartoons drawn from a dizzying array of public entertainments which were expanding rapidly in the late nineteenth century. Minstrel shows, circuses, melodrama, and Shakespearean allusions made regular appearances in Grip. In keeping with the editor’s passion for the theatre, especially plays espousing a reform-oriented politics, Grip published The Sweet Girl Graduate (1882) by Sarah Anne Curzon. The closet drama takes up the  cause of higher education for women—through a cross-dressing heroine infiltrating the University of Toronto—and was written at Bengough’s request.

cause of higher education for women—through a cross-dressing heroine infiltrating the University of Toronto—and was written at Bengough’s request.

In the early days, Bengough relied on his company, J. W. Bengough & Co., to publish his magazine. He and his brothers, Thomas and George, particularly with the latter’s help, transitioned their efforts beyond Grip to encompass a host of printing, engraving, and other publishing jobs. Their firm, Bengough Bros., also acted as agents for various American publications such as Scribners’ Monthly, St. Nicholas, and the Detroit Free Press. In 1881 a new company was formed, only to be replaced by another the following year. The Grip Printing and Publishing Company offered public shares and was governed by a board of directors. The new business paved the way for expansion, both for the printing company and Grip. By 1883, the magazine’s readership had grown, reaching between 7,000  and 10,000 subscribers and, according to its own calculations, as many as 50,000 readers.

and 10,000 subscribers and, according to its own calculations, as many as 50,000 readers.

The printing company produced everything from small printing jobs, such as souvenir booklets for the Ontario town of Owen Sound, to more substantial works: Mrs. Clarke’s Cookery Book (1883); Bengough’s own two-volume, A Caricature History of Canadian Politics (1886); and Principal Grant’s Inaugural Address Delivered at Queen’s University, Kingston, on University Day, 1885 (1885). The firm capitalized on the  North-West Rebellion of 1885 with Major Charles A. Boulton’s Reminiscences of the North-West Rebellions (1886), as well as an 18-issue publication called the Illustrated War News (later titled Canadian Pictorial and Illustrated War News.) It also published the Educational Journal, School Work and Play, The Grip-Sack, Grip’s Comic Almanac, the Labor Advocate, and the Ontario Gazette.

North-West Rebellion of 1885 with Major Charles A. Boulton’s Reminiscences of the North-West Rebellions (1886), as well as an 18-issue publication called the Illustrated War News (later titled Canadian Pictorial and Illustrated War News.) It also published the Educational Journal, School Work and Play, The Grip-Sack, Grip’s Comic Almanac, the Labor Advocate, and the Ontario Gazette.

Not until the 1890s did political cartoons become a staple of mainstream North American newspapers. Scholars agree that technological restrictions made it difficult and expensive to print these kinds of images on a large scale. As a publisher anxious to keep costs down, Bengough was attuned to technological  developments. His fortuitous experience with lithography in 1872, for instance, helped spur his decision to found Grip. Indeed, advances in photolithography and zinc engraving made it easier and cheaper to reproduce cartoons. In addition, these technologies allowed artists like Bengough greater freedom in the complexity and nuance of their art. As the technology emerged to replace wood engraving with photoengraving and other innovations, cartooning became feasible for daily publications.

developments. His fortuitous experience with lithography in 1872, for instance, helped spur his decision to found Grip. Indeed, advances in photolithography and zinc engraving made it easier and cheaper to reproduce cartoons. In addition, these technologies allowed artists like Bengough greater freedom in the complexity and nuance of their art. As the technology emerged to replace wood engraving with photoengraving and other innovations, cartooning became feasible for daily publications.

As Bruce Retallack argues, however, technology was not the only force restricting cartoons from mainstream publications. A distrust of images and a privileging of text as the only medium solemn enough for the news meant that  editorial cartooning on a large scale would have to wait until the final decades of the nineteenth century. From the heated press wars of the later part of the century emerged a focus on popular journalism which was more amenable to the cartoonist’s pen. In many respects, one of Bengough’s lasting achievements as a publisher and political cartoonist was to help Victorians come to terms with images. He demonstrated that editorial cartoons could be serious and important while simultaneously exuding playfulness, irony, and satiric charm. Nowhere is this more evident than in Bengough’s depictions of Sir John A. Macdonald. Indeed, the image most people have of Canada’s first prime minister comes from the artist’s wittily acerbic pen. Bengough was a pioneer of English Canadian editorial cartooning. His work set stylistic and technological precedents for a future generation of artists, including Sam Hunter, Owen Staples, and A.G. Racey, who all honed their skills at Grip. They, like Bengough himself, eventually migrated to daily newspapers. In so doing, they expanded the market for such images. As Cumming concludes, Bengough’s innovation was to make cartoons a legitimate part of journalism.

editorial cartooning on a large scale would have to wait until the final decades of the nineteenth century. From the heated press wars of the later part of the century emerged a focus on popular journalism which was more amenable to the cartoonist’s pen. In many respects, one of Bengough’s lasting achievements as a publisher and political cartoonist was to help Victorians come to terms with images. He demonstrated that editorial cartoons could be serious and important while simultaneously exuding playfulness, irony, and satiric charm. Nowhere is this more evident than in Bengough’s depictions of Sir John A. Macdonald. Indeed, the image most people have of Canada’s first prime minister comes from the artist’s wittily acerbic pen. Bengough was a pioneer of English Canadian editorial cartooning. His work set stylistic and technological precedents for a future generation of artists, including Sam Hunter, Owen Staples, and A.G. Racey, who all honed their skills at Grip. They, like Bengough himself, eventually migrated to daily newspapers. In so doing, they expanded the market for such images. As Cumming concludes, Bengough’s innovation was to make cartoons a legitimate part of journalism.

After founding the magazine at the age of 22, Bengough was forced out of Grip on 6 August 1892. Some contemporaries believed that Bengough lost touch with his audience—becoming too radical. His brother Thomas, however, levelled allegations of mismanagement against other board members. Conflicts amongst the board and some shareholders most likely facilitated Bengough’s departure. The magazine ceased publication on 15 July 1893, although the printing company continued. After a brief sojourn as cartoonist for the Montreal Star, Bengough attempted to revive his old magazine in January 1894. The effort proved short-lived, and Grip’s last issue appeared on 29 December 1894. Although Bengough continued working until his death in 1923, his golden period as a Canadian publisher ended with Grip’s final demise.

After founding the magazine at the age of 22, Bengough was forced out of Grip on 6 August 1892. Some contemporaries believed that Bengough lost touch with his audience—becoming too radical. His brother Thomas, however, levelled allegations of mismanagement against other board members. Conflicts amongst the board and some shareholders most likely facilitated Bengough’s departure. The magazine ceased publication on 15 July 1893, although the printing company continued. After a brief sojourn as cartoonist for the Montreal Star, Bengough attempted to revive his old magazine in January 1894. The effort proved short-lived, and Grip’s last issue appeared on 29 December 1894. Although Bengough continued working until his death in 1923, his golden period as a Canadian publisher ended with Grip’s final demise.

Bengough, Thomas. “Life and Work of J. W. Bengough, Canada’s Cartoonist.”

http://www.canadianshakespeares.ca/a_bengough.cfm

Blake, Denis Edward. “J.W. Bengough and Grip: The Canadian Editorial Cartoon Comes of Age.” MA thesis, Wilfrid Laurier University, 1985.

Burr, Christina. “Gender, Sexuality, and Nationalism in J.W. Bengough’s Verses and Political Cartoons,” Canadian Historical Review 83: 4 (2002): 505-54.

Cook, Ramsay. The Regenerators: Social Criticism in Late Victorian English Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985.

—. “John Wilson Bengough.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Online edition:

http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?BioId=42029

Cumming, Carman. Sketches from a Young Country: The Images of “Grip” Magazine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Desbarats, Peter and Terry Mosher. The Hecklers: A History of Canadian Political Cartooning and a Cartoonists’ History of Canada. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1979.

Kutcher, Stanley Paul. “John Wilson Bengough: Artist of Righteousness.” MA thesis, McMaster University, 1975.

Mendelson, Alan. “Grip Magazine and ‘the Other’: The Genteel Antisemitism of J.W. Bengough.” Histoire Sociale 40: 79 (2007): 1-44.

Retallack, G. Bruce. “Drawing the Lines: Gender, Class, Race and Nation in Canadian Editorial Cartoons, 1840-1926.” PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2006.

Spadoni, Carl. “Grip and the Bengoughs as Publishers and Printers.” Papers of the Bibliographic Society of Canada 27 (1988): 12-37.

J.W. Bengough fonds, McMaster University