Publishers’ Catalogues and a Chariot on Yonge Street: Marketing Canadian Books

Carl Spadoni, McMaster University

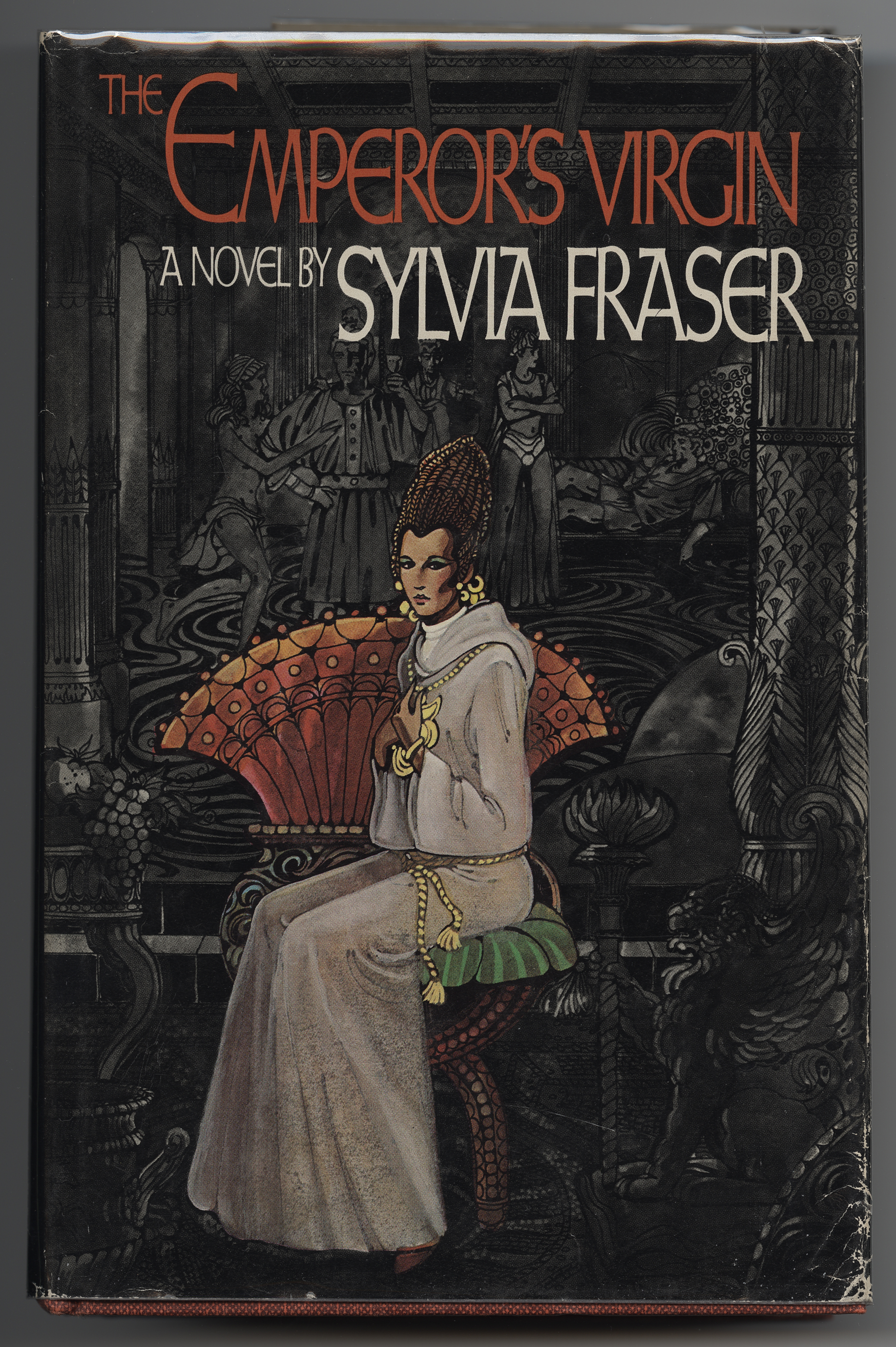

In order to survive, Canadian publishers have had to rely on many methods to market and to sell books: subscription publishing, government contracts and  subsidies, acting as agents on behalf of other publishers, subsidiary rights, advertising campaigns, reviews in newspapers and other media, exhibits in book stores, book fairs, publicity stunts, and book tours. On the Ides of March in 1980, to launch the publication of Sylvia Fraser’s The Emperor's Virgin, Jack McClelland, the master impresario of book promotion, hired a chariot on Yonge Street in Toronto and dressed himself, Fraser, and the charioteers in sandals and togas. A blizzard forced this strange entourage into a Coles bookstore for shelter, but McClelland’s seemingly disastrous antics gained him national attention. One of McClelland’s chief authors, the prolific Pierre Berton, loved book tours and the

subsidies, acting as agents on behalf of other publishers, subsidiary rights, advertising campaigns, reviews in newspapers and other media, exhibits in book stores, book fairs, publicity stunts, and book tours. On the Ides of March in 1980, to launch the publication of Sylvia Fraser’s The Emperor's Virgin, Jack McClelland, the master impresario of book promotion, hired a chariot on Yonge Street in Toronto and dressed himself, Fraser, and the charioteers in sandals and togas. A blizzard forced this strange entourage into a Coles bookstore for shelter, but McClelland’s seemingly disastrous antics gained him national attention. One of McClelland’s chief authors, the prolific Pierre Berton, loved book tours and the  limelight. When The Secret World of Og, his best-selling children’s novel, was published on 7 October 1961, McClelland & Stewart (M&S) sent a tape recording to all radio stations in Canada of Berton reading excerpts from the book to his children [Pierre_Berton_recording.mp3 below]. If a radio station promoted Berton’s book, then it would receive a percentage of the sales at local bookstores. Another Berton publicity campaign by M&S, for The Great Railway, Illustrated in 1972, saw the distribution of a unique and impressive promotional package that included cut plug tobacco, a cigar, pemmican, and moustache wax.

limelight. When The Secret World of Og, his best-selling children’s novel, was published on 7 October 1961, McClelland & Stewart (M&S) sent a tape recording to all radio stations in Canada of Berton reading excerpts from the book to his children [Pierre_Berton_recording.mp3 below]. If a radio station promoted Berton’s book, then it would receive a percentage of the sales at local bookstores. Another Berton publicity campaign by M&S, for The Great Railway, Illustrated in 1972, saw the distribution of a unique and impressive promotional package that included cut plug tobacco, a cigar, pemmican, and moustache wax.

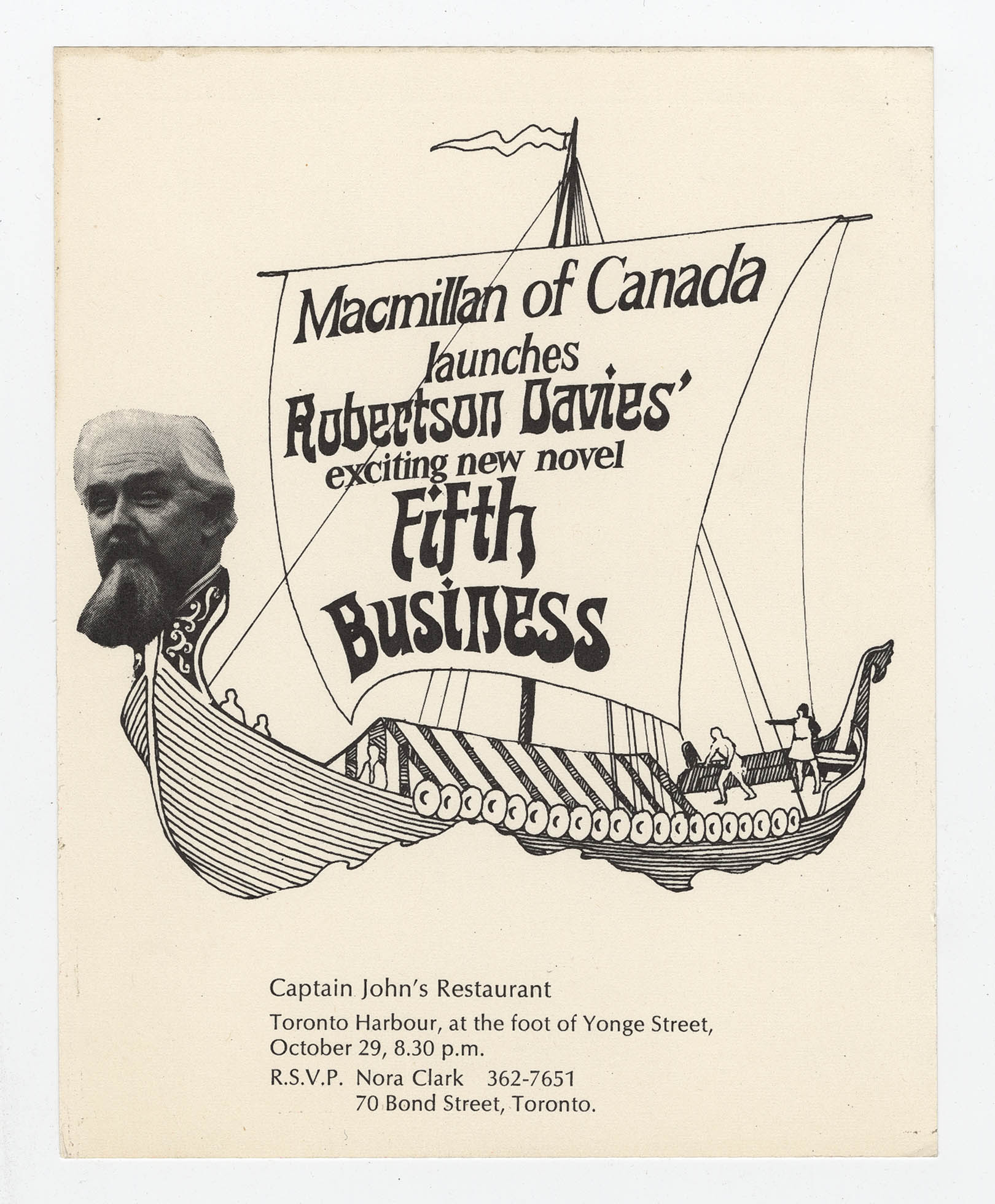

The launches of other books were somewhat more traditional but nonetheless  creative. On 29 October 1970, for example, Macmillan of Canada launched Robertson Davies’s novel, Fifth Business, at Captain John’s Restaurant in Toronto Harbour “in keeping with the subject and tone of the novel”−the location in the novel where Percy Boyd Staunton had drowned in his Cadillac convertible. The Macmillan Company spent $518 promoting Fifth Business before publication, $918 in promotion after publication (ads in newspapers, releases to literary editors, posters in bookstores, etc.), and approximately $500 on the launch at Captain John’s Restaurant.

creative. On 29 October 1970, for example, Macmillan of Canada launched Robertson Davies’s novel, Fifth Business, at Captain John’s Restaurant in Toronto Harbour “in keeping with the subject and tone of the novel”−the location in the novel where Percy Boyd Staunton had drowned in his Cadillac convertible. The Macmillan Company spent $518 promoting Fifth Business before publication, $918 in promotion after publication (ads in newspapers, releases to literary editors, posters in bookstores, etc.), and approximately $500 on the launch at Captain John’s Restaurant.

Jack McClelland’s “coat of many authors”, which is used as the logo of this website, is a jacket silkscreened with images of the covers of M&S books. It  was designed by Maggy Reeves, a high-fashion couturier in Toronto, and worn by the publisher when he distributed free books on the streets of Canadian cities. The jacket was donated by McClelland’s family to McMaster University Library in 2008.

was designed by Maggy Reeves, a high-fashion couturier in Toronto, and worn by the publisher when he distributed free books on the streets of Canadian cities. The jacket was donated by McClelland’s family to McMaster University Library in 2008.

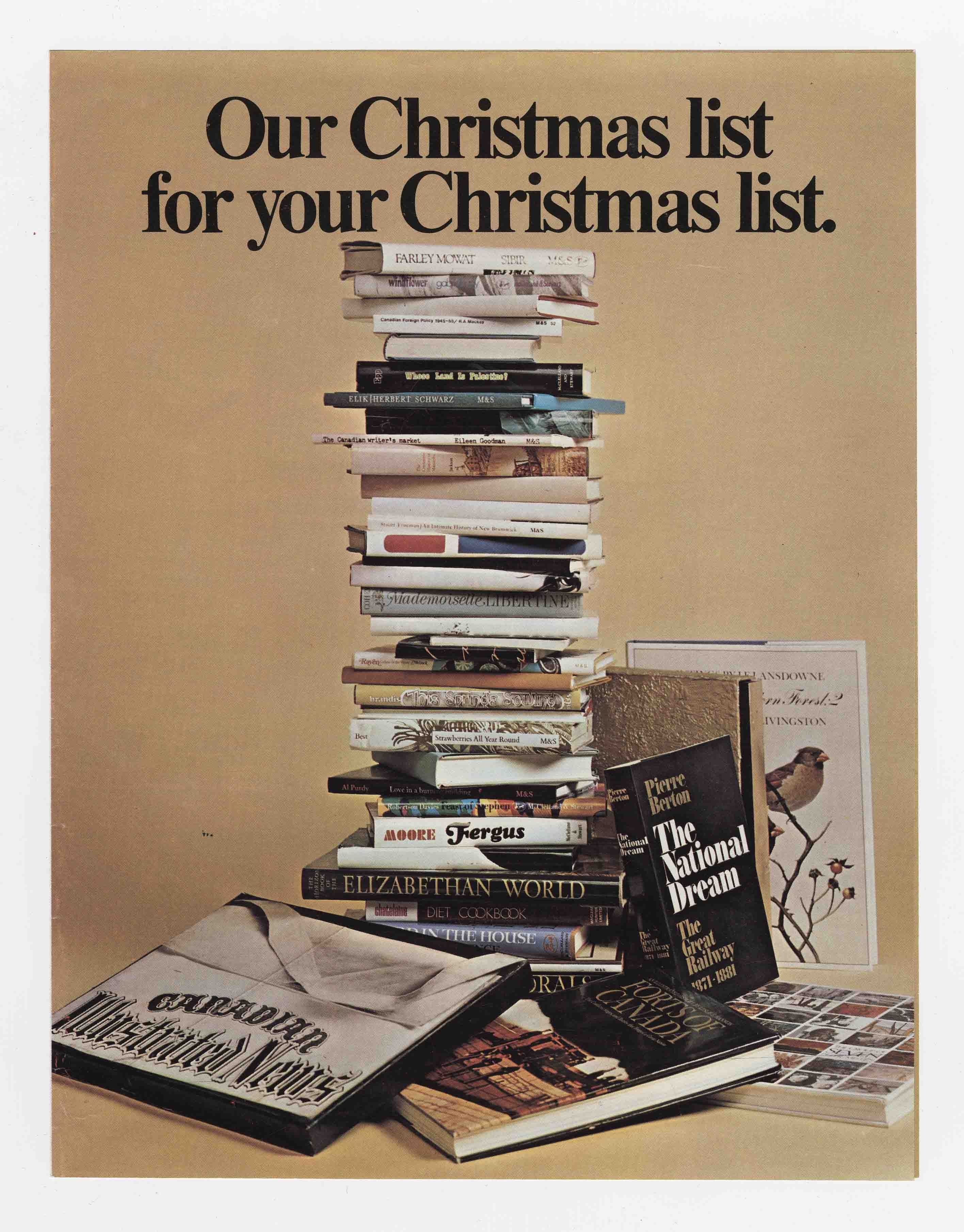

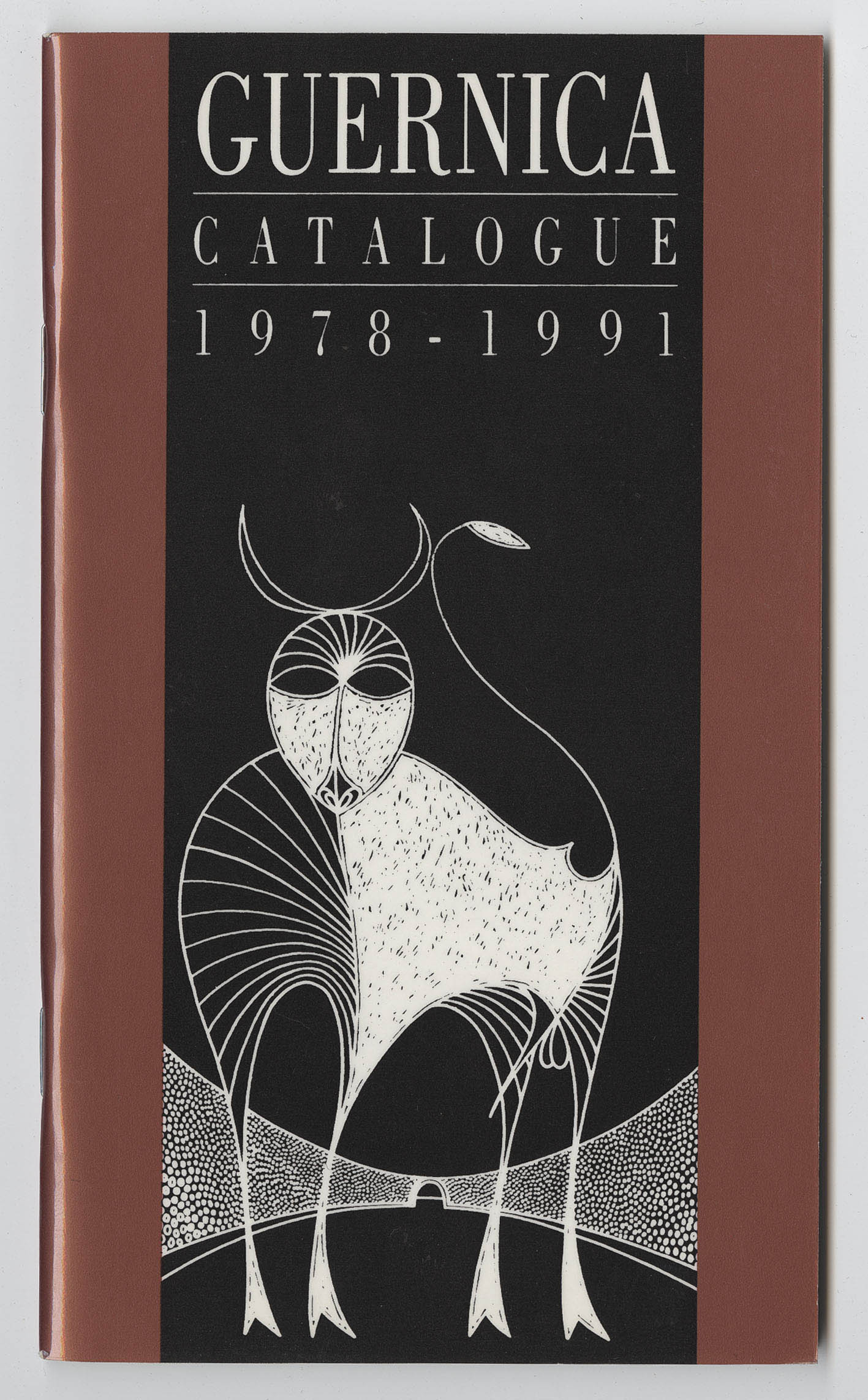

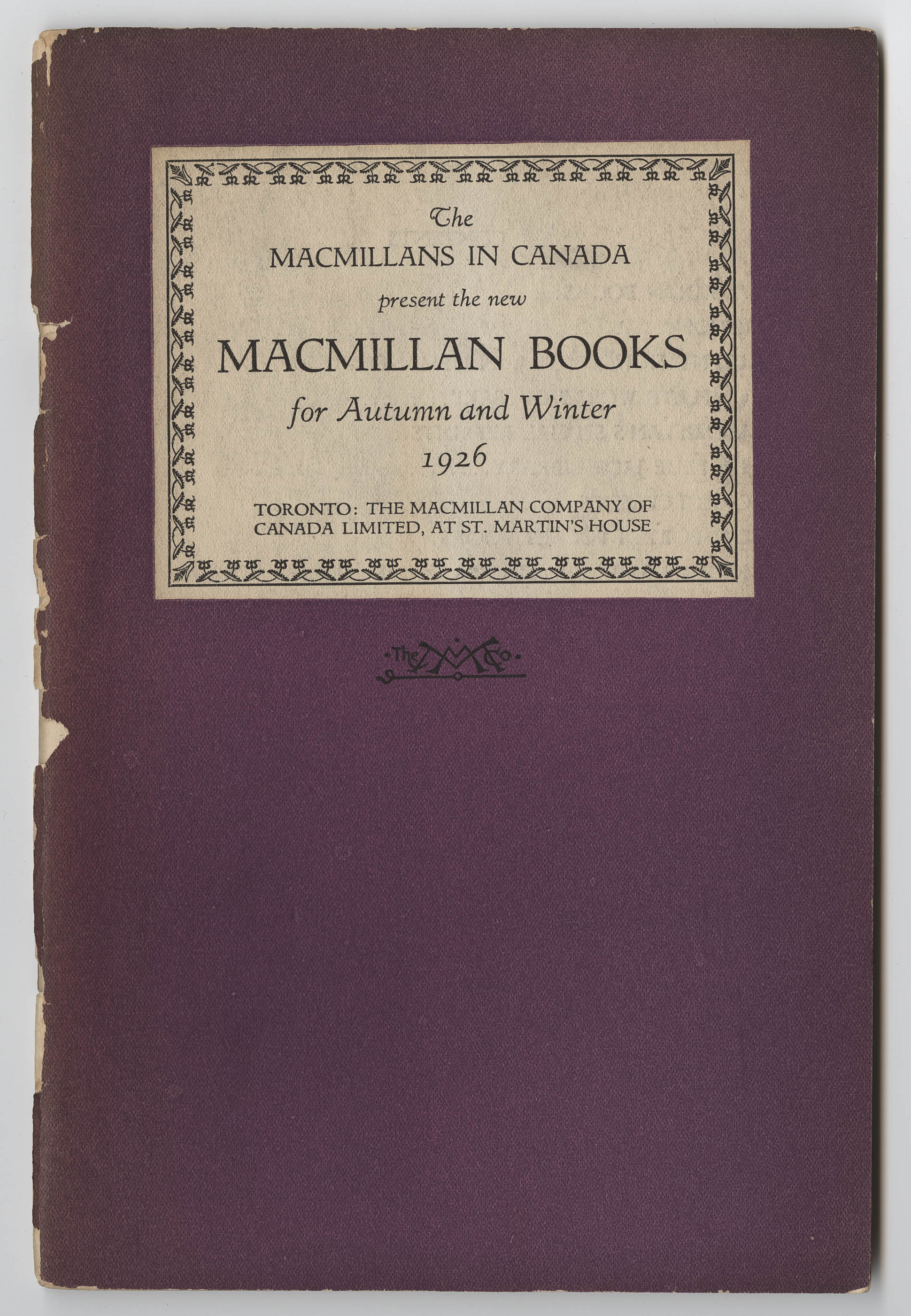

In more conventional marketing terms, publishers’ catalogues have always been a mainstay in Canadian publishing. They tell the public about recently published books and other books in stock (author, title, price, an illustration of the book’s jacket, an abstract, and a “blurb”−a nicely chosen quotation from a glowing review). Catalogues routinely appear according to the seasons of the year. The winter catalogue was timed for the holidays when shoppers would go  to bookstores in search of seasonal gifts. Catalogues would be mailed en masse to bookstores, authors, potential customers, and other media outlets. When book salesmen, such as John Saul and Gladys Neale of Macmillan of Canada, travelled by train across Canada in the first decades of the twentieth century, they would usually carry dummy or sample books and catalogues to show off to representatives in the trade. Publishers have also issued catalogues on special occasions, to emphasize certain themes (young readers, Sunday school libraries, books in series, games and toys, Canadian literature) or to celebrate anniversaries or achievements (the 1978-1991 catalogue of Guernica Editions, for example,

to bookstores in search of seasonal gifts. Catalogues would be mailed en masse to bookstores, authors, potential customers, and other media outlets. When book salesmen, such as John Saul and Gladys Neale of Macmillan of Canada, travelled by train across Canada in the first decades of the twentieth century, they would usually carry dummy or sample books and catalogues to show off to representatives in the trade. Publishers have also issued catalogues on special occasions, to emphasize certain themes (young readers, Sunday school libraries, books in series, games and toys, Canadian literature) or to celebrate anniversaries or achievements (the 1978-1991 catalogue of Guernica Editions, for example,  was issued to celebrate the publication of its 100th book). In spite of the public’s increasing use of the Internet for information, many catalogues continue to be distributed in hard copy with a digital surrogate conveniently found at the website of the publisher, and publishers have found the Internet itself to be an extraordinary tool for the publicity and sales of books.

was issued to celebrate the publication of its 100th book). In spite of the public’s increasing use of the Internet for information, many catalogues continue to be distributed in hard copy with a digital surrogate conveniently found at the website of the publisher, and publishers have found the Internet itself to be an extraordinary tool for the publicity and sales of books.

The earliest extant catalogue of a Canadian publisher, dated 1800, is from John Neilson (1776-1848), a printer, publisher, and bookseller in Lower Canada, who specialized in religious works and school texts and published the Quebec Gazette / La Gazette de Québec, other newspapers, and government proclamations and statutes. Neilson’s 1800 catalogue of 265 titles of books, primarily in English, is arranged by subject or genre (classics, dictionaries, French and English grammar and school books, political pamphlets, plays, etc.). Other catalogues, which were issued by Neilson in 1802, 1803, 1811, 1817, and 1818, have been studied in terms of their social significance by the historians John Hare and Jean-Pierre Wallot. Neilson’s catalogues list not just books published under his own imprint but books from many different publishers−an indication that early Canadian publishers took on many roles related to general bookselling and as stationers and agents.

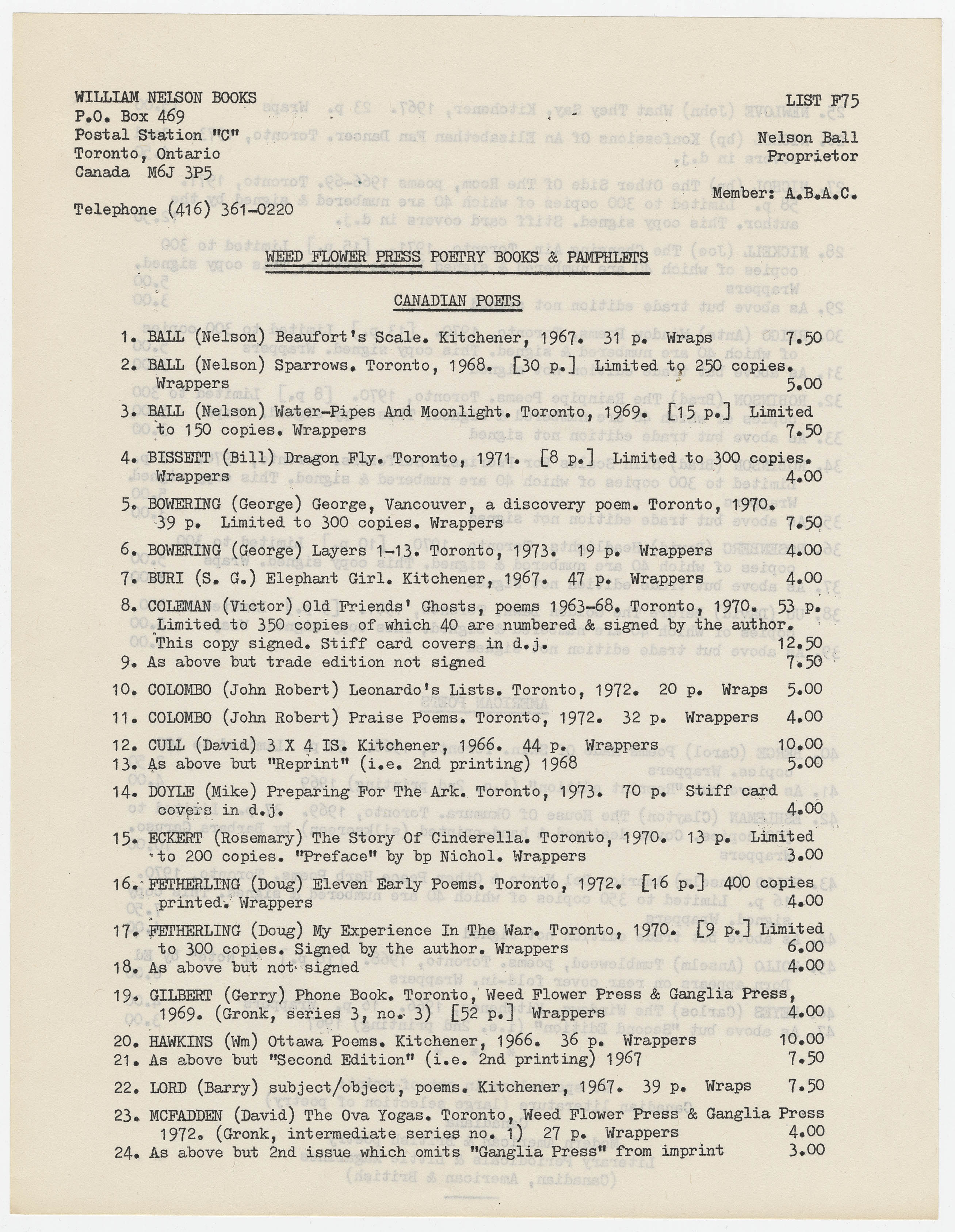

Publishers’ archives contain a variety of catalogues. At the most basic level, they record a publisher’s stock of books. Some catalogues are quite plain and consist of a few pages of essential information; others are flashy, beautifully designed productions and are almost books in themselves. Even avant guard, fine press, and small press publishers, such as the contemporary Curvd H&Z (Ottawa), Locks’ Press (Kingston), and Weed / Flower Press (operated by Nelson Ball in Kitchener and Toronto between 1966 and 1973) have produced catalogues. M&S’s earliest catalogues, issued in the company’s inaugural incarnations as McClelland & Goodchild (1906-14) and McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart

Publishers’ archives contain a variety of catalogues. At the most basic level, they record a publisher’s stock of books. Some catalogues are quite plain and consist of a few pages of essential information; others are flashy, beautifully designed productions and are almost books in themselves. Even avant guard, fine press, and small press publishers, such as the contemporary Curvd H&Z (Ottawa), Locks’ Press (Kingston), and Weed / Flower Press (operated by Nelson Ball in Kitchener and Toronto between 1966 and 1973) have produced catalogues. M&S’s earliest catalogues, issued in the company’s inaugural incarnations as McClelland & Goodchild (1906-14) and McClelland, Goodchild & Stewart  (1914-8), provide information about the firm as a representative and agent for other publishers; books are listed under many categories, such as popular fiction, new books of importance, holiday and finely illustrated books, travel books, essays and general literature, and biography, letters, and history. In McClelland & Goodchild’s “Canadiana” catalogue circa 1910, there are quotations of national sentiment: “‘Janey Canuck in the West’ should be Read by every Canadian”; “‘Wacousta’ by Richardson is the Canadian Ivanhoe.”

(1914-8), provide information about the firm as a representative and agent for other publishers; books are listed under many categories, such as popular fiction, new books of importance, holiday and finely illustrated books, travel books, essays and general literature, and biography, letters, and history. In McClelland & Goodchild’s “Canadiana” catalogue circa 1910, there are quotations of national sentiment: “‘Janey Canuck in the West’ should be Read by every Canadian”; “‘Wacousta’ by Richardson is the Canadian Ivanhoe.”

Publishers’ catalogues are products of their time, hinting and sometimes revealing how promotion, advertising, and marketing techniques intersect with genre, gender, class, religion, politics, and tastes in literature. At the same time they must be used with other documents in publishers’ archives and other sources in piecing together a story. A case in point is the stylish catalogue of Graphic Publishers Limited of Ottawa for 1931-2. Fiercely nationalistic, Graphic published only indigenous Canadian books produced entirely in Canada. The catalogue’s attractive cover in pink, black, and white features a man, comfortably seated, smoking a pipe, and reading a book. The catalogue discusses the origins of the publisher’s logo or trade mark: the Thunderbird, a native motif “emblematic of strength, force and success.” Several

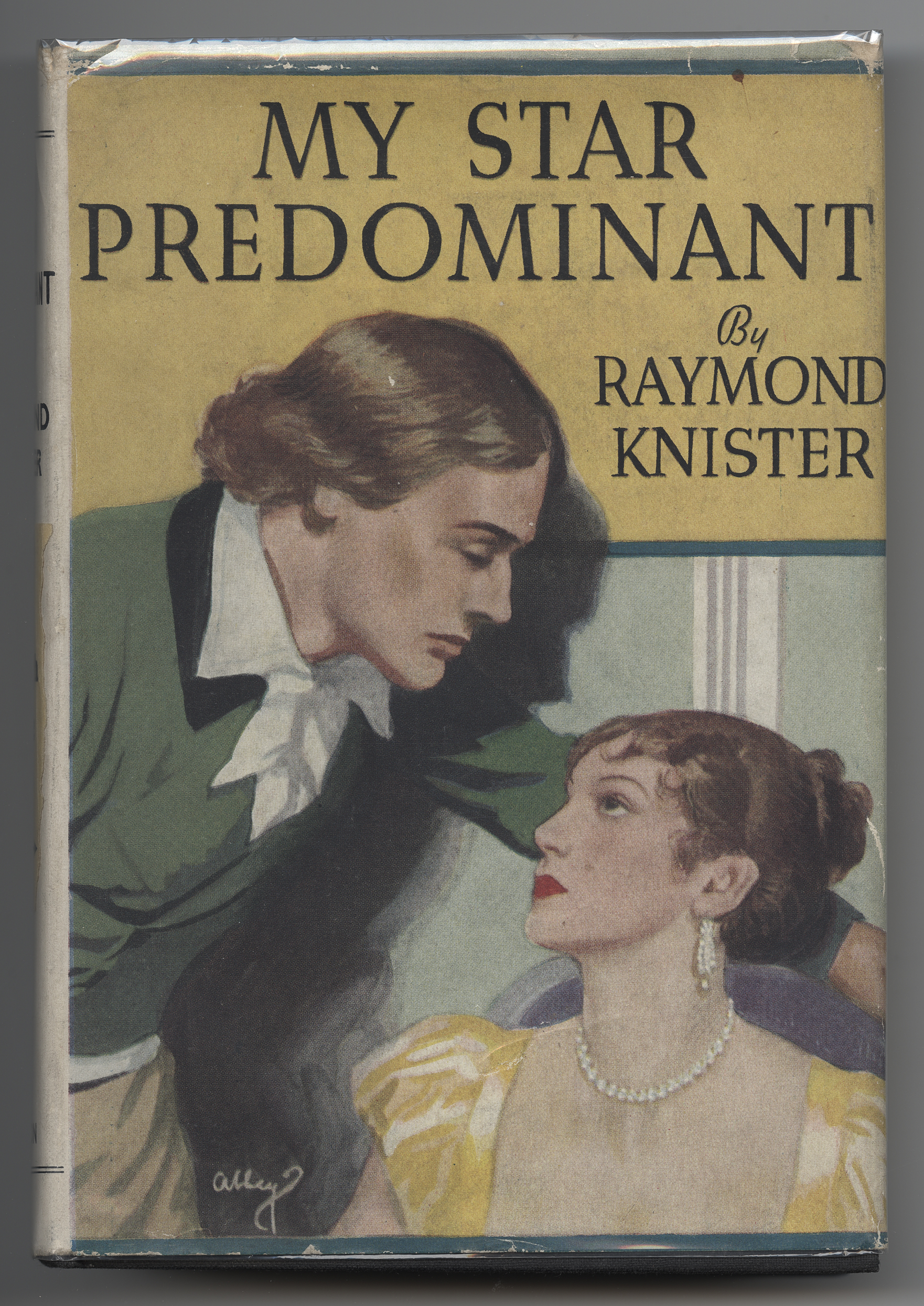

Publishers’ catalogues are products of their time, hinting and sometimes revealing how promotion, advertising, and marketing techniques intersect with genre, gender, class, religion, politics, and tastes in literature. At the same time they must be used with other documents in publishers’ archives and other sources in piecing together a story. A case in point is the stylish catalogue of Graphic Publishers Limited of Ottawa for 1931-2. Fiercely nationalistic, Graphic published only indigenous Canadian books produced entirely in Canada. The catalogue’s attractive cover in pink, black, and white features a man, comfortably seated, smoking a pipe, and reading a book. The catalogue discusses the origins of the publisher’s logo or trade mark: the Thunderbird, a native motif “emblematic of strength, force and success.” Several  pages have descriptions of books in the Canada Series, including Stephen Leacock’s edition of La Hontan’s Voyages. The advertisement for Raymond Knister’s My Star Predominant proudly notes that the novel has been awarded the first prize in Graphic’s novel contest. Graphic’s catalogue was in fact its swan song. The company went bankrupt shortly thereafter at the height of the Depression. Although the Leacock edition of La Hontan’s Voyages was published, Leacock was never paid for his editorial work and did not receive a copy of the book. Knister’s novel was published in 1934 by the Ryerson Press.

pages have descriptions of books in the Canada Series, including Stephen Leacock’s edition of La Hontan’s Voyages. The advertisement for Raymond Knister’s My Star Predominant proudly notes that the novel has been awarded the first prize in Graphic’s novel contest. Graphic’s catalogue was in fact its swan song. The company went bankrupt shortly thereafter at the height of the Depression. Although the Leacock edition of La Hontan’s Voyages was published, Leacock was never paid for his editorial work and did not receive a copy of the book. Knister’s novel was published in 1934 by the Ryerson Press.

The value of catalogues for the study of book history, publishing, and  literary history cannot be understated. Catalogues show the strengths and specialties of publishing houses, their alliances, and their priorities. The works of individual authors are documented in great detail in their pages, with the success of specific writers and titles demonstrated by the reprints, new editions, and translations promoted in the catalogues. Usually designed with great care and often with flourish, catalogues showcase the skills of the designers employed by the publishing houses, and for that reason are themselves valuable for the study of book design and graphics. The detailed information on book prices included in catalogues is of great value to those interested in the economics of publishing, while descriptions of formats, limited editions, and other details of the physical book, are most valuable for bibliographers of all persuasions. In today’s era of the digital revolution, marketing managers in Canadian publishing have resorted to many different new techniques to promote their books. Monique Trottier, the former Internet marketing manager of Raincoast Books, for example, has conducted Web-based marketing campaigns, including online promotion of Harry Potter and the creation of the first Canadian-publisher podcast and blog. However old-fashioned, catalogues remain an important marketing tool for Canadian publishers.

literary history cannot be understated. Catalogues show the strengths and specialties of publishing houses, their alliances, and their priorities. The works of individual authors are documented in great detail in their pages, with the success of specific writers and titles demonstrated by the reprints, new editions, and translations promoted in the catalogues. Usually designed with great care and often with flourish, catalogues showcase the skills of the designers employed by the publishing houses, and for that reason are themselves valuable for the study of book design and graphics. The detailed information on book prices included in catalogues is of great value to those interested in the economics of publishing, while descriptions of formats, limited editions, and other details of the physical book, are most valuable for bibliographers of all persuasions. In today’s era of the digital revolution, marketing managers in Canadian publishing have resorted to many different new techniques to promote their books. Monique Trottier, the former Internet marketing manager of Raincoast Books, for example, has conducted Web-based marketing campaigns, including online promotion of Harry Potter and the creation of the first Canadian-publisher podcast and blog. However old-fashioned, catalogues remain an important marketing tool for Canadian publishers.

Alston, Sandra. “Canada’s First Bookseller’s Catalogue”, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada, 30 (spring 1992): 7-26.

Kotin, David B. “Graphic Publishers and the Bibliographer: An Introduction and Checklist”, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada, 18 (1979): 47-54.

Lamonde, Yvan and Rotundo, Andrea. “The Book Trade and Bookstores.” In History of the Book in Canada, ed. Patricia Lockhart Fleming, Yvan Lamonde, and Gilles Gallichan, I: 124-37. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd. fonds, McMaster University

Jack McClelland fonds, McMaster University

Nelson Ball fonds, McMaster University