Creative Dialogue Across the Ocean: Eric Aldwinckle’s Letters to Harry Somers

Eric Aldwinckle was working as a graphic design artist and as an instructor at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto when the Second World War broke out in Europe. A conscientious objector, he stayed away from the battlefront until he was appointed to the War Artists Group in late 1942. He set off for England in 1943, where he was attached to the Coastal Command and Fighter Command. Refusing to limit his correspondence to dull 'bread and butter” matters, Aldwinckle's letters to Harry Somers and Ruth Somers (Harry's mother) poetically explore his experience as an agent of creativity in his various roles: as mentor to the blossoming Harry, as a writer acutely aware of his reader, and as an artist struggling to express the strange dynamic of war while meeting the demands of his higher-ups. Sixteen years Harry Somers' senior, Aldwinckle's close friendship with Somers seems unlikely at first. However, this collection of 31 of his letters reveals the fundamental principle underlying their relationship: a love for truth, beauty, and ideals – in other words, the creative experience.

In Somers, Aldwinckle finds not only a student and intimate pal -- he also finds inspiration. The younger man’s youthful talent spurs Aldwinckle to fund Somers' studies and he presents Somers' String Quartet to Boosey & Hawkes, a London-based music publishing house. When Leslie Boosey declines to publish the Quartet, Aldwinckle forwards the rejection letter to Somers, and writes on the back: 'Publishing and publications are honey combed with much more intricate channels than the simple 'recognition of talent.'' From the RCAF Headquarters in England, Aldwinckle also aggressively defends Somers against the attacks of the Toronto critic Augustus Bridle, composing a scathing letter (+ p2) in which he criticizes Bridle for discouraging rather than celebrating young artists who continue to create in spite of the war. Aldwinckle's commitment to supporting Somers' musical ambitions remains steadfast, despite the ocean separating them.

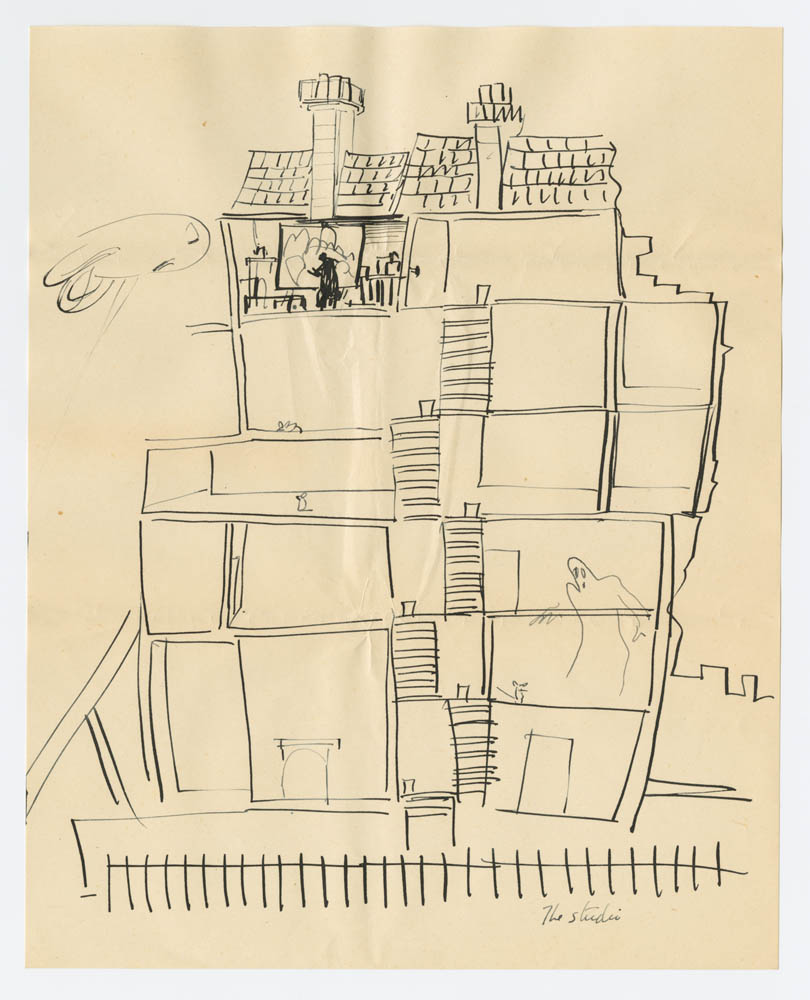

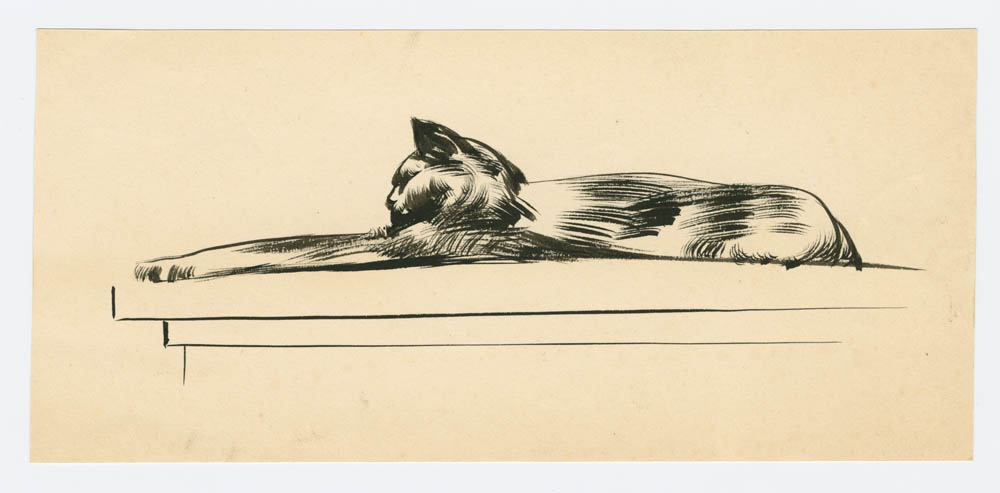

Aldwinckle is very self-conscious about his position as a letter writer. He regards letter writing as an art, and his letters are infused with the same imaginative force and careful construction as one might find in his paintings. Knowing that his letters are at the mercy of the censor, however, Aldwinckle has to write within artistic limits, leaving him 'poetically bursting.' Early on in the correspondence, Aldwinckle even jokingly considers giving up letter writing, because he finds it 'too exasperating.' He does not try to downplay the effort he puts into his letters. For example, he tells Somers: 'I write and am interrupted, or prevented from completing it and when I come back to pick up the thread I read it and say 'not interesting' 'not worth reading' so I commence another.' The same thing happens over and over, until Aldwinckle finally mails all of the rejected, unfinished pieces in a bundle for Somers to read. This bundle consists of prose, poetry, and a dialogue -- forms not uncharacteristic of the rest of Aldwinckle's letters. In another instance, Aldwinckle fills six pages to Ruth with descriptions of the wasps infesting the camp. He even encloses a watercolour of a wasp climbing out of a trap he fashions out of a tin of sweets, and, evidently pleased with his composition, tells Somers that he is making a copy of the letter for another friend!

Aldwinckle is very self-conscious about his position as a letter writer. He regards letter writing as an art, and his letters are infused with the same imaginative force and careful construction as one might find in his paintings. Knowing that his letters are at the mercy of the censor, however, Aldwinckle has to write within artistic limits, leaving him 'poetically bursting.' Early on in the correspondence, Aldwinckle even jokingly considers giving up letter writing, because he finds it 'too exasperating.' He does not try to downplay the effort he puts into his letters. For example, he tells Somers: 'I write and am interrupted, or prevented from completing it and when I come back to pick up the thread I read it and say 'not interesting' 'not worth reading' so I commence another.' The same thing happens over and over, until Aldwinckle finally mails all of the rejected, unfinished pieces in a bundle for Somers to read. This bundle consists of prose, poetry, and a dialogue -- forms not uncharacteristic of the rest of Aldwinckle's letters. In another instance, Aldwinckle fills six pages to Ruth with descriptions of the wasps infesting the camp. He even encloses a watercolour of a wasp climbing out of a trap he fashions out of a tin of sweets, and, evidently pleased with his composition, tells Somers that he is making a copy of the letter for another friend!

The letters in this collection reveal that Aldwinckle is not solely an artist by profession; the driving force in his life is a burning quest for beauty. When he first arrives in London, he busies himself with searching for pianos on which to practice, seeing plays by Noel Coward, going to concerts at Wigmore Hall, and taking a lithography course at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. He writes a great deal about communing with nature; one of his letters is dedicated entirely to describing the view from 12,000 feet up in the sky. He quotes from John Clare's poem 'I Am,' and considers the irony of communing with nature from within the confines of a vibrating airplane. Perhaps this quest for beauty is the basis of Aldwinckle's fondness for Somers; Somers, a budding young composer, inspires hope in Aldwinckle, who is beginning to recognize the fruitlessness of his own musical ambitions. In a letter that describes his fantasy of canoeing alone with Somers, in Canadian waters, underneath the stars, Aldwinckle writes: 'The great desire I have is to simply 'BE' with thee and in fact with all those who are beautiful and good in my eyes.'

Aldwinckle's letters to Somers shed light on some of Aldwinckle's most famous works, currently housed at the Canadian War Museum. In his letter of 23 December 1943, he discusses the creation of 'Return from Berlin.' Aldwinckle spent a week at a bomber station to prepare for his painting. What he saw was 'indelibly impressed' upon him, and he waited impatiently for the arrival of a large canvas. By this time, his vision for the painting has more or less taken on a life of its own, and waits to pour itself out onto a canvas. Once he commits it to canvas, he writes: 'Anything I have done before this simply doesn't count, except be a tool for this. I am almost in fear of being lost afterwards...'

Aldwinckle's letters also deal with the discrepancy between his intentions as an artist and the way his art is received. He jokes that his paintings are 'taken from [him] like eggs from a hen,' and he addresses the artist's dilemma of reconciling the demands of the market with his creative freedom. Aldwinckle tells Somers that a prisoner of war he had met earlier has written to him, urging him to complete 'The Survivor': 'Dear Eric that painting you had on your easel has been haunting me. Unfinished as it was it possessed some quality that I haven't been able to forget. It's good Eric! For God's sake finish it, then perhaps I'll see it in the future and get it off my mind.' Upon which Aldwinckle reflects:

Aldwinckle's letters also deal with the discrepancy between his intentions as an artist and the way his art is received. He jokes that his paintings are 'taken from [him] like eggs from a hen,' and he addresses the artist's dilemma of reconciling the demands of the market with his creative freedom. Aldwinckle tells Somers that a prisoner of war he had met earlier has written to him, urging him to complete 'The Survivor': 'Dear Eric that painting you had on your easel has been haunting me. Unfinished as it was it possessed some quality that I haven't been able to forget. It's good Eric! For God's sake finish it, then perhaps I'll see it in the future and get it off my mind.' Upon which Aldwinckle reflects:

'It is so stimulating to get some real live reaction from someone who also has experienced these things that it comes as a heartener. So often has my finished work met the silent, unknowing and uncaring eye of administration to be whisked away to the silent unknown that I have been feeling sometimes as one robbed -- I have sung, I have shouted -- screamed or merely commented artistically but there has been no answer, until I have felt justified in believing that I was talking to myself and there seemed no point in speaking words of experience in a locked room. My field notes are exhibited -- my messages or my feelings have been hidden -- They will perhaps come to light later -- who knows. It doesn't matter.'

The fact that Aldwinckle’s artwork did matter, at least for posterity, is demonstrated by its prominent position in the Canadian War Museum. Like these pictorial works of art, his letters to Harry and Ruth Somers deserve to be carefully examined and thoughtfully considered.